Potter's wheel

In pottery, a potter's wheel is a machine used in the shaping (known as throwing) of round ceramic ware. The wheel may also be used during the process of trimming the excess body from dried ware, and for applying incised decoration or rings of colour. Use of the potter's wheel became widespread throughout the Old World but was unknown in the Pre-Columbian New World, where pottery was handmade by methods that included coiling and beating.

A potter's wheel may occasionally be referred to as a "potter's lathe". However, that term is better used for another kind of machine that is used for a different shaping process, turning, similar to that used for shaping of metal and wooden articles.

The techniques of jiggering and jolleying can be seen as extensions of the potter's wheel: in jiggering, a shaped tool is slowly brought down onto the plastic clay body that has been placed on top of the rotating plaster mould. The jigger tool shapes one face, the mould the other. The term is specific to the shaping of flat ware, such as plates, whilst a similar technique, jolleying, refers to the production of hollow ware, such as cups.

History[edit]

Much early ceramic ware was hand-built using a simple coiling technique in which clay was rolled into long threads that were then pinched and smoothed together to form the body of a vessel. In the coiling method of construction, all the energy required to form the main part of a piece is supplied indirectly by the hands of the potter. Early ceramics built by coiling were often placed on mats or large leaves to allow them to be worked more conveniently. The evidence of this lies in mat or leaf impressions left in the clay of the base of the pot. This arrangement allowed the potter to rotate the vessel during construction, rather than walk around it to add coils of clay.

The earliest forms of the potter's wheel (called tourneys or slow wheels) were probably developed as an extension to this procedure. Tournettes, in use around 4500 BC in the Near East, were turned slowly by hand or by foot while coiling a pot. Only a small range of vessels were fashioned on the tournette, suggesting that it was used by a limited number of potters.[1] The introduction of the slow wheel increased the efficiency of hand-powered pottery production.

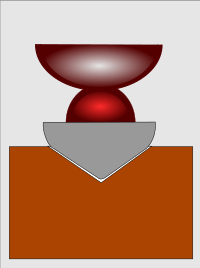

In the mid to late 3rd millennium BC the fast wheel was developed, which operated on the flywheel principle. It utilised energy stored in the rotating mass of the heavy stone wheel itself to speed the process. This wheel was wound up and charged with energy by kicking, or pushing it around with a stick, providing a centrifugal force. The fast wheel enabled a new process of pottery-making to develop, called throwing, in which a lump of clay was placed centrally on the wheel and then squeezed, lifted and shaped as the wheel turned. The process tends to leave rings on the inside of the pot and can be used to create thinner-walled pieces and a wider variety of shapes, including stemmed vessels, so wheel-thrown pottery can be distinguished from handmade. Potters could now produce many more pots per hour, a first step towards industrialization.

Many modern scholars suggest that the first potter's wheel was first developed by the ancient Sumerians in Mesopotamia.[2] A stone potter's wheel found at the Sumerian city of Ur in modern-day Iraq has been dated to about 3129 BC,[3] but fragments of wheel-thrown pottery of an even earlier date have been recovered in the same area.[3] However, southeastern Europe[4] and China[5] have also been claimed as possible places of origin. Furthermore, the wheel was also in popular use by potters starting around 3500 BC in major cities of the Indus Valley civilization in South Asia, namely Harappa and Mohenjo-daro (Kenoyer, 2005). Others consider Egypt as "being the place of origin of the potter's wheel. It was here that the turntable shaft was lengthened about 3000 BC and a flywheel added. The flywheel was kicked and later was moved by pulling the edge with the left hand while forming the clay with the right. This led to the counterclockwise motion for the potter's wheel which is almost universal."[6] Hence the exact origin of the wheel is not wholly clear yet.

In the Iron Age, the potter's wheel in common use had a turning platform about one metre (3 feet) above the floor, connected by a long axle to a heavy flywheel at ground level. This arrangement allowed the potter to keep the turning wheel rotating by kicking the flywheel with the foot, leaving both hands free for manipulating the vessel under construction. However, from an ergonomic standpoint, sweeping the foot from side to side against the spinning hub is rather awkward. At some point, an alternative solution was invented that involved a crankshaft with a lever that converted up-and-down motion into rotary motion.

The use of the motor-driven wheel has become common in modern times, particularly with craft potters and educational institutions, although human-powered ones are still in use and are preferred by some studio potters.

Techniques of throwing[edit]

There are many techniques in use for throwing ceramic shapes, although this is a typical entry-level procedure:

A recently wedged, slightly lumpy clump of plastic throwing clay is slapped, thrown or otherwise affixed to the wheel-head or a bat. A bat serves as a proxy wheel-head that can be removed with the finished pot. The wedged clay is centered by the speed of the wheel and the steadiness of the potter's hands. Water is used as a lubricant to control the clay and should be used sparingly as it also weakens the clay as it get thinner. It is important to ease onto and off of the clay so that the entire circumference receives the same treatment. A high speed on the wheel (240-300 rpm) makes this operation much easier with less physical exertion needed by the potter. The potter will sit or stand with the wheel-head as close to their waist as possible, allowing them more stability and strength. The wheel is sped up and the potter brings steady, controlled pressure onto the clay starting with the blades of the hands where the clay meets the wheel, working your way up. When the clay is centered the clay needs to be homogenized. The more shear (engineering definition) energy that is applied to the clay, the more strength it has later in pulling up the walls and allows the potter to throw faster and with thinner walls. The operation is sometimes called exercising or wheel wedging the clay and consists of thinning and applying shear energy to as much of the clay as possible while keeping the clay whole and centered. After wheel wedging and centering the clay the next step is to open the clay and set the floor of the pot. This is still done at high speed so that the clay in the floor of the pot receives enough shear energy. To open the clay, softly feel for the center of the clay, having your finger in the center will require the least amount of work. Once you have found center push down towards the wheel-head to set the floor thickness of the pot. When you have established the floor thickness, pull the clay out to establish the floor width. The ring of clay surrounding the floor is now ready to be pulled up into the walls of the pot. The first pull is started at full or near full speed to thin the walls. For right-handed potters working on a wheel going counter-clockwise the left hand is on the inside of the ring on the right hand on the outside at the right tangent of the wheel. The second and third pulls establish the thickness and shape.

A skilled potter can quickly throw a vessel from up to 15 kg (30 lb) of clay.[7] Alternatively, by throwing and adding coils of clay then throwing again, pots up to four feet high may be made, the heat of a blowlamp being used to firm each thrown section before adding the next coil. In Chinese manufacture, very large pots are made by two throwers working simultaneously.

The potter's wheel in myth and legend[edit]

In Ancient Egyptian mythology, the deity Khnum was said to have formed the first humans on a potter's wheel.

References[edit]

- ^ Roux, Valentine; Miroschedji, Pierre (2009). "Revisiting the History of the Potter's Wheel in the Southern Levant". Levant. 41 (2): 155–173.

- ^ Kramer, Samuel Noah (1963). The Sumerians: Their History, Culture, and Character. Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press. p. 290. ISBN 0-226-45238-7.

- ^ a b Moorey, Peter Roger Stuart (1999) [1994]. Ancient Mesopotamian Materials and Industries: The Archaeological Evidence. Winona Lake, Indiana: Eisenbrauns. p. 146. ISBN 9781575060422.

- ^ Cucoș, Ștefan (1999). "Faza Cucuteni B în zona subcarpatică a Moldovei" [Cucuteni B period in the lower Carpathian region of Moldova]. Bibliotheca Memoriae antiquitatis (BMA) (Memorial Library antiquities) (in Romanian). Piatra Neamț, Romania: Muzeul de Istorie Piatra Neamț (Historical Museum Piatra Neamț). 6. OCLC 223302267.

- ^ "萧山日报-数字报纸". Archived from the original on 2011-07-07.

- ^ Hamer, Frank; Hamer, Janet (2004). The Potter's Dictionary of Materials and Techniques. p. 383.

- ^ "Isaac Button – Country Potter (1965)". Film & TV Database. BFI.

External links[edit]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Potter's wheel. |

- Pottery (video on Internet Archive)

- Earliest Depiction of a Kick-Wheel in Egypt

- Isaac Button, Soil Hill Pottery near Halifax, England; Lakeside Pottery

- The last Iranian woman potter using the ancient technique. Location: Pirtaj village in Chang-almas region in western Iran; Lakeside Pottery

- Pottery Wheels - The Ceramic Shop Kolokol

→←→→···§§§§←÷