Musical film

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

(Learn how and when to remove this template message)

|

Musical film is a film genre in which songs by the characters are interwoven into the narrative, sometimes accompanied by dancing.

The songs usually advance the plot or develop the film's characters, but in some cases, they serve merely as breaks in the storyline, often as elaborate "production numbers."

The musical film was a natural development of the stage musical after the emergence of sound film technology. Typically, the biggest difference between film and stage musicals is the use of lavish background scenery and locations that would be impractical in a theater. Musical films characteristically contain elements reminiscent of theater; performers often treat their song and dance numbers as if a live audience were watching. In a sense, the viewer becomes the diegetic audience, as the performer looks directly into the camera and performs to it.

Hollywood musical films[edit]

1930-1950 : The first classical sound era or First Musical Era[edit]

The 1930s through the early 1950s are considered to be the golden age of the musical film, when the genre's popularity was at its highest in the Western world. Disney's Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, the earliest Disney animated feature film, was a musical which won an honorary Oscar for Walt Disney at the 11th Academy Awards.

The first musicals[edit]

Musical short films were made by Lee de Forest in 1923–24. Beginning in 1926, thousands of Vitaphone shorts were made, many featuring bands, vocalists, and dancers. The earliest feature-length films with synchronized sound had only a soundtrack of music and occasional sound effects that played while the actors portrayed their characters just as they did in silent films: without audible dialogue.[1] The Jazz Singer, released in 1927 by Warner Brothers, was the first to include an audio track including non-diegetic music and diegetic music, but it had only a short sequence of spoken dialogue. This feature-length film was also a musical, featuring Al Jolson singing "Dirty Hands, Dirty Face", "Toot, Toot, Tootsie", "Blue Skies", and "My Mammy". Historian Scott Eyman wrote, "As the film ended and applause grew with the houselights, Sam Goldwyn's wife Frances looked around at the celebrities in the crowd. She saw 'terror in all their faces', she said, as if they knew that 'the game they had been playing for years was finally over'."[2] Still, only isolated sequences featured "live" sound; most of the film had only a synchronous musical score.[1] In 1928, Warner Brothers followed this up with another Jolson part-talkie, The Singing Fool, which was a blockbuster hit.[1] Theaters scrambled to install the new sound equipment and to hire Broadway composers to write musicals for the screen.[3] The first all-talking feature, Lights of New York, included a musical sequence in a night club. The enthusiasm of audiences was so great that in less than a year all the major studios were making sound pictures exclusively. The Broadway Melody (1929) had a show-biz plot about two sisters competing for a charming song-and-dance man. Advertised by MGM as the first "All-Talking, All-Singing, All-Dancing" feature film, it was a hit and won the Academy Award for Best Picture for 1929. There was a rush by the studios to hire talent from the stage to star in lavishly filmed versions of Broadway hits. The Love Parade (Paramount 1929) starred Maurice Chevalier and newcomer Jeanette MacDonald, written by Broadway veteran Guy Bolton.[3]

Warner Brothers produced the first screen operetta, The Desert Song in 1929. They spared no expense and photographed a large percentage of the film in Technicolor. This was followed by the first all-color, all-talking musical feature which was entitled On with the Show (1929). The most popular film of 1929 was the second all-color, all-talking feature which was entitled Gold Diggers of Broadway (1929). This film broke all box office records and remained the highest-grossing film ever produced until 1939. Suddenly, the market became flooded with musicals, revues, and operettas. The following all-color musicals were produced in 1929 and 1930 alone: The Show of Shows (1929), Sally (1929), The Vagabond King (1930), Follow Thru (1930), Bright Lights (1930), Golden Dawn (1930), Hold Everything (1930), The Rogue Song (1930), Song of the Flame (1930), Song of the West (1930), Sweet Kitty Bellairs (1930), Under a Texas Moon (1930), Bride of the Regiment (1930), Whoopee! (1930), King of Jazz (1930), Viennese Nights (1930), and Kiss Me Again (1930). In addition, there were scores of musical features released with color sequences.

Hollywood released more than 100 musical films in 1930, but only 14 in 1931.[4] By late 1930, audiences had been oversaturated with musicals and studios were forced to cut the music from films that were then being released. For example, Life of the Party (1930) was originally produced as an all-color, all-talking musical comedy. Before it was released, however, the songs were cut out. The same thing happened to Fifty Million Frenchmen (1931) and Manhattan Parade (1932) both of which had been filmed entirely in Technicolor. Marlene Dietrich sang songs successfully in her films, and Rodgers and Hart wrote a few well-received films, but even their popularity waned by 1932.[4] The public had quickly come to associate color with musicals and thus the decline in their popularity also resulted in a decline in color productions.

Busby Berkeley[edit]

The taste in musicals revived again in 1933 when director Busby Berkeley began to enhance the traditional dance number with ideas drawn from the drill precision he had experienced as a soldier during World War I. In films such as 42nd Street and Gold Diggers of 1933 (1933), Berkeley choreographed a number of films in his unique style. Berkeley's numbers typically begin on a stage but gradually transcend the limitations of theatrical space: his ingenious routines, involving human bodies forming patterns like a kaleidoscope, could never fit onto a real stage and the intended perspective is viewing from straight above.[5]

Musical stars[edit]

Musical stars such as Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers were among the most popular and highly respected personalities in Hollywood during the classical era; the Fred and Ginger pairing was particularly successful, resulting in a number of classic films, such as Top Hat (1935), Swing Time (1936), and Shall We Dance (1937). Many dramatic actors gladly participated in musicals as a way to break away from their typecasting. For instance, the multi-talented James Cagney had originally risen to fame as a stage singer and dancer, but his repeated casting in "tough guy" roles and mob films gave him few chances to display these talents. Cagney's Oscar-winning role in Yankee Doodle Dandy (1942) allowed him to sing and dance, and he considered it to be one of his finest moments.

Many comedies (and a few dramas) included their own musical numbers. The Marx Brothers' films included a musical number in nearly every film, allowing the Brothers to highlight their musical talents. Their final film, entitled Love Happy (1949), featured Vera-Ellen, considered to be the best dancer among her colleagues and professionals in the half century.

Similarly, The vaudevillian comedian W. C. Fields joined forces with the comic actress Martha Raye and the young comedian Bob Hope in Paramount Pictures musical anthology The Big Broadcast of 1938. The film also showcased the talents of several internationally recognized musical artists including: Kirsten Flagstad (Norwegian operatic soprano), Wilfred Pelletier (Canadian conductor of the Metropolitan Opera Orchestra, Tito Guizar (Mexican tenor), Shep Fields conducting his Rippling Rhythm Jazz Orchestra and John Serry Sr. (Italian-American concert accordionist).[6] In addition to the Academy Award for Best Original Song (1938), the film earned an ASCAP Film and Television Award (1989) for Bob Hope's signature song "Thanks for the Memory".[7]

The Freed Unit[edit]

During the late 1940s and into the early 1950s, a production unit at Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer headed by Arthur Freed made the transition from old-fashioned musical films, whose formula had become repetitive, to something new. (However, they also produced Technicolor remakes of such musicals as Show Boat, which had previously been filmed in the 1930s.) In 1939, Freed was hired as associate producer for the film Babes in Arms. Starting in 1944 with Meet Me in St. Louis, the Freed Unit worked somewhat independently of its own studio to produce some of the most popular and well-known examples of the genre. The products of this unit include Easter Parade (1948), On the Town (1949), An American in Paris (1951), Singin' in the Rain (1952), The Band Wagon (1953) and Gigi (1958). Non-Freed musicals from the studio included Seven Brides for Seven Brothers in 1954 and High Society in 1956, and the studio distributed Samuel Goldwyn's Guys and Dolls in 1955.

This era saw musical stars become household names, including Judy Garland, Gene Kelly, Ann Miller, Donald O'Connor, Cyd Charisse, Mickey Rooney, Vera-Ellen, Jane Powell, Howard Keel, and Kathryn Grayson. Fred Astaire was also coaxed out of retirement for Easter Parade and made a permanent comeback.

Outside MGM[edit]

The other Hollywood studios proved themselves equally adept at tackling the genre at this time, particularly in the 1950s. Four adaptations of Rodgers and Hammerstein shows - Oklahoma!, The King and I, Carousel, and South Pacific - were all successes, while Paramount Pictures released White Christmas and Funny Face, two films which used previously written music by Irving Berlin and the Gershwins, respectively. Warner Bros. produced Calamity Jane and A Star Is Born; the former film was a vehicle for Doris Day, while the latter provided a big-screen comeback for Judy Garland, who had been out of the spotlight since 1950. Meanwhile, director Otto Preminger, better known for controversial "message pictures", made Carmen Jones and Porgy and Bess, both starring Dorothy Dandridge, who is considered the first African American A-list film star. Celebrated director Howard Hawks also ventured into the genre with Gentlemen Prefer Blondes.

This section possibly contains original research. (October 2010) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

In the 1960s, 1970s, and continuing up to today, the musical film became less of a bankable genre that could be relied upon for sure-fire hits. Audiences for them lessened and fewer musical films were produced as the genre became less mainstream and more specialized.

The 1960s musical[edit]

In the 1960s, the critical and box-office success of the films West Side Story, Gypsy, The Music Man, Bye Bye Birdie, My Fair Lady, Mary Poppins, The Sound of Music, A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum, The Jungle Book, Thoroughly Modern Millie, Oliver!, and Funny Girl suggested that the traditional musical was in good health, while French filmmaker Jacques Demy's jazz musicals The Umbrellas of Cherbourg and The Young Girls of Rochefort were popular with international critics. However popular musical tastes were being heavily affected by rock and roll and the freedom and youth associated with it, and indeed Elvis Presley made a few films that have been equated with the old musicals in terms of form, though A Hard Day's Night and Help!, starring the Beatles, were more technically audacious. Most of the musical films of the 1950s and 1960s such as Oklahoma! and The Sound of Music were straightforward adaptations or restagings of successful stage productions. The most successful musicals of the 1960s created specifically for film were Mary Poppins and The Jungle Book, two of Disney's biggest hits of all time.

The phenomenal box-office performance of The Sound of Music gave the major Hollywood studios more confidence to produce lengthy, large-budget musicals. Despite the resounding success of some of these films, Hollywood also produced a large number of musical flops in the late 1960s and early 1970s which appeared to seriously misjudge public taste. The commercially and/or critically unsuccessful films included Camelot, Finian's Rainbow, Hello Dolly!, Sweet Charity, Doctor Dolittle, Half a Sixpence, The Happiest Millionaire, Star!, Darling Lili, Goodbye, Mr. Chips, Paint Your Wagon, Song of Norway, On a Clear Day You Can See Forever, Man of La Mancha, Lost Horizon, and Mame. Collectively and individually these failures crippled several of the major studios.

1970s[edit]

In the 1970s, film culture and the changing demographics of filmgoers placed greater emphasis on gritty realism, while the pure entertainment and theatricality of classical-era Hollywood musicals was seen as old-fashioned. Despite this, Fiddler on the Roof and Cabaret were more traditional musicals closely adapted from stage shows and were strong successes with critics and audiences. Changing cultural mores and the abandonment of the Hays Code in 1968 also contributed to changing tastes in film audiences. The 1973 film of Andrew Lloyd Webber and Tim Rice's Jesus Christ Superstar was met with some criticism by religious groups but was well received. By the mid-1970s, filmmakers avoided the genre in favor of using music by popular rock or pop bands as background music, partly in hope of selling a soundtrack album to fans. The Rocky Horror Picture Show was originally released in 1975 and was a critical failure until it started midnight screenings in the 1980s where it achieved cult status. 1976 saw the release of the low-budget comic musical, The First Nudie Musical, released by Paramount. The 1978 film version of Grease was a smash hit; its songs were original compositions done in a 1950s pop style. However, the sequel Grease 2 (released in 1982) bombed at the box-office. Films about performers which incorporated gritty drama and musical numbers interwoven as a diegetic part of the storyline were produced, such as Lady Sings the Blues, All That Jazz, and New York, New York. Some musicals made in Britain experimented with the form, such as Richard Attenborough's Oh! What a Lovely War (released in 1969), Alan Parker's Bugsy Malone and Ken Russell's Tommy and Lisztomania.

A number of film musicals were still being made that were financially and/or critically less successful than in the musical's heyday. They include 1776, The Wiz, At Long Last Love, Mame, Man of La Mancha, Lost Horizon, Godspell, Phantom of the Paradise, Funny Lady (Barbra Streisand's sequel to Funny Girl), A Little Night Music, and Hair amongst others. The critical wrath against At Long Last Love, in particular, was so strong that it was never released on home video. Fantasy musical films Scrooge, The Blue Bird, The Little Prince, Willy Wonka & the Chocolate Factory, Pete's Dragon, and Disney's Bedknobs and Broomsticks were also released in the 1970s, the latter winning the Academy Award for Best Visual Effects.

1980s to 1990s[edit]

By the 1980s, financiers grew increasingly confident in the musical genre, partly buoyed by the relative health of the musical on Broadway and London's West End. Productions of the 1980s and 1990s included The Apple, Xanadu, The Blues Brothers, Annie, Monty Python's The Meaning of Life, The Best Little Whorehouse in Texas, Victor Victoria, Footloose, Fast Forward, A Chorus Line, Little Shop of Horrors, Forbidden Zone, Absolute Beginners, Labyrinth, Evita, and Everyone Says I Love You. However, Can't Stop the Music, starring the Village People, was a calamitous attempt to resurrect the old-style musical and was released to audience indifference in 1980. Little Shop of Horrors was based on an off-Broadway musical adaptation of a 1960 Roger Corman film, a precursor of later film-to-stage-to-film adaptations, including The Producers.

Many animated films of the period – predominately from Disney – included traditional musical numbers. Howard Ashman, Alan Menken, and Stephen Schwartz had previous musical theater experience and wrote songs for animated films during this time, supplanting Disney workhorses the Sherman Brothers. Starting with 1989's The Little Mermaid, the Disney Renaissance gave new life to the musical film. Other successful animated musicals included Aladdin, The Hunchback of Notre Dame, and Pocahontas from Disney proper, The Nightmare Before Christmas from Disney division Touchstone Pictures, The Prince of Egypt from DreamWorks, Anastasia from Fox and Don Bluth, and South Park: Bigger, Longer & Uncut from Paramount. (Beauty and the Beast and The Lion King were adapted for the stage after their blockbuster success.)

2014-now : The second-classical era or New Musical Era[edit]

21st-century musicals or New Age[edit]

In the 21st century, movie musicals were reborn with darker musicals, musical biopics, epic drama musicals and comedy-drama musicals such as Moulin Rouge!, Chicago, Walk the Line, Dreamgirls, Sweeney Todd: The Demon Barber of Fleet Street, Les Misérables and La La Land; all of which won the Golden Globe Award for Best Motion Picture – Musical or Comedy in their respective years, while such films as The Phantom of the Opera, Hairspray, Mamma Mia!, Nine, Into the Woods, The Greatest Showman, Mary Poppins Returns, and Rocketman were only nominated. Chicago was also the first musical since Oliver! to win Best Picture at the Academy Awards.

Joshua Oppenheimer's Academy Award-nominated documentary The Act of Killing may be considered a nonfiction musical.[8]

One specific musical trend was the rising number of jukebox musicals based on music from various pop/rock artists on the big screen, some of which based on Broadway shows. Examples of Broadway-based jukebox musical films included Mamma Mia! (ABBA), Rock of Ages, and Sunshine on Leith (The Proclaimers). Original ones included Across the Universe (The Beatles), Moulin Rouge! (various pop hits), Idlewild (Outkast) and Yesterday (The Beatles).

Disney also returned to musicals with Enchanted, The Princess and the Frog, Tangled, Winnie the Pooh, The Muppets, Frozen, Muppets Most Wanted, Into the Woods, Moana, Mary Poppins Returns and Frozen II. Following a string of successes with live action fantasy adaptations of several of their animated features, Disney produced a live action version of Beauty and the Beast, the first of this live action fantasy adaptation pack to be an all-out musical, and features new songs as well as new lyrics to both the Gaston number and the reprise of the title song. The second film of this live action fantasy adaptation pack to be an all-out musical was Aladdin and features new songs. The third film of this live action fantasy adaptation pack to be an all-out musical was The Lion King and features new songs. Pixar also produced Coco, the very first computer-animated musical film by the company.

Other animated musical films include Rio, Trolls, Sing, Smallfoot and UglyDolls. Biopics about music artists and showmen were also big in the 21st century. Examples include 8 Mile (Eminem), Ray (Ray Charles), Walk the Line (Johnny Cash and June Carter), La Vie en Rose (Édith Piaf), Notorious (Biggie Smalls), Jersey Boys (The Four Seasons) Love & Mercy (Brian Wilson), CrazySexyCool: The TLC Story (TLC), Aaliyah: The Princess of R&B (Aaliyah), Get on Up (James Brown), Whitney (Whitney Houston), Straight Outta Compton (N.W.A), The Greatest Showman (P. T. Barnum), Bohemian Rhapsody (Freddie Mercury),[citation needed] The Dirt (Mötley Crüe) and Rocketman (Elton John).

Director Damien Chazelle created a musical film called La La Land, starring Ryan Gosling and Emma Stone. It was meant to reintroduce the traditional jazz style of song numbers with influences from the Golden Age of Hollywood and Jacques Demy's French musicals while incorporating a contemporary/modern take on the story and characters with balances in fantasy numbers and grounded reality. It received 14 nominations at the 89th Academy Awards, tying the record for most nominations with All About Eve (1950) and Titanic (1997), and won the awards for Best Director, Best Actress, Best Cinematography, Best Original Score, Best Original Song, and Best Production Design.

Indian musical films[edit]

An exception to the decline of the musical film is Indian cinema, especially the Bollywood film industry based in Mumbai (formerly Bombay), where the most of films have been and still are musicals. The majority of films produced in the Tamil industry based in Chennai (formerly Madras), Sandalwood based in Bangalore, Telugu industry based in Hyderabad, and Malayalam industry are also musicals.

Despite this exception of almost every Indian movie being a musical and India producing the most number of movies in the world (Formed in 1913), the first Bollywood film to be a complete musical Dev D (Directed by Anurag Kashyap) came in the year 2009. The second film to follow its track was Jagga Jasoos (Directed by Anurag Basu) in the year 2017.

Early sound films (1930s–1940s)[edit]

Bollywood musicals have their roots in the traditional musical theatre of India, such as classical Indian musical theatre, Sanskrit drama, and Parsi theatre. Early Bombay filmmakers combined these Indian musical theatre traditions with the musical film format that emerged from early Hollywood sound films.[9] Other early influences on Bombay filmmakers included Urdu literature and the Arabian Nights.[10]

The first Indian sound film, Ardeshir Irani's Alam Ara (1931), was a major commercial success.[11] There was clearly a huge market for talkies and musicals; Bollywood and all the regional film industries quickly switched to sound filming.

In 1937, Ardeshir Irani, of Alam Ara fame, made the first colour film in Hindi, Kisan Kanya. The next year, he made another colour film, a version of Mother India. However, colour did not become a popular feature until the late 1950s. At this time, lavish romantic musicals and melodramas were the staple fare at the cinema.

Golden Age (late 1940s–1960s)[edit]

Following India's independence, the period from the late 1940s to the early 1960s is regarded by film historians as the "Golden Age" of Hindi cinema.[15][16][17] Some of the most critically acclaimed Hindi films of all time were produced during this period. Examples include Pyaasa (1957) and Kaagaz Ke Phool (1959) directed by Guru Dutt and written by Abrar Alvi, Awaara (1951) and Shree 420 (1955) directed by Raj Kapoor and written by Khwaja Ahmad Abbas, and Aan (1952) directed by Mehboob Khan and starring Dilip Kumar. These films expressed social themes mainly dealing with working-class life in India, particularly urban life in the former two examples; Awaara presented the city as both a nightmare and a dream, while Pyaasa critiqued the unreality of city life.[18]

Mehboob Khan's Mother India (1957), a remake of his earlier Aurat (1940), was the first Indian film to be nominated for the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film, which it lost by a single vote.[19] Mother India was also an important film that defined the conventions of Hindi cinema for decades.[20][21][22]

In the 1960s and early 1970s, the industry was dominated by musical romance films with "romantic hero" leads, the most popular being Rajesh Khanna.[23] Other actors during this period include Shammi Kapoor, Jeetendra, Sanjeev Kumar, and Shashi Kapoor, and actresses like Sharmila Tagore, Mumtaz, Saira Banu, Helen and Asha Parekh.

Classic Bollywood (1970s–1980s)[edit]

By the start of the 1970s, Hindi cinema was experiencing thematic stagnation,[24] dominated by musical romance films.[23] The arrival of screenwriter duo Salim-Javed, consisting of Salim Khan and Javed Akhtar, marked a paradigm shift, revitalizing the industry.[24] They began the genre of gritty, violent, Bombay underworld crime films in the early 1970s, with films such as Zanjeer (1973) and Deewaar (1975).[25][26]

The 1970s was also when the name "Bollywood" was coined,[27][28] and when the quintessential conventions of commercial Bollywood films were established.[29] Key to this was the emergence of the masala film genre, which combines elements of multiple genres (action, comedy, romance, drama, melodrama, musical). The masala film was pioneered in the early 1970s by filmmaker Nasir Hussain,[30] along with screenwriter duo Salim-Javed,[29] pioneering the Bollywood blockbuster format.[29] Yaadon Ki Baarat (1973), directed by Hussain and written by Salim-Javed, has been identified as the first masala film and the "first" quintessentially "Bollywood" film.[31][29] Salim-Javed went on to write more successful masala films in the 1970s and 1980s.[29] Masala films launched Amitabh Bachchan into the biggest Bollywood movie star of the 1970s and 1980s. A landmark for the masala film genre was Amar Akbar Anthony (1977),[32][31] directed by Manmohan Desai and written by Kader Khan. Manmohan Desai went on to successfully exploit the genre in the 1970s and 1980s.

Along with Bachchan, other popular actors of this era included Feroz Khan,[33] Mithun Chakraborty, Naseeruddin Shah, Jackie Shroff, Sanjay Dutt, Anil Kapoor and Sunny Deol. Actresses from this era included Hema Malini, Jaya Bachchan, Raakhee, Shabana Azmi, Zeenat Aman, Parveen Babi, Rekha, Dimple Kapadia, Smita Patil, Jaya Prada and Padmini Kolhapure.[34]

New Bollywood (1990s–present)[edit]

In the late 1980s, Hindi cinema experienced another period of stagnation, with a decline in box office turnout, due to increasing violence, decline in musical melodic quality, and rise in video piracy, leading to middle-class family audiences abandoning theaters. The turning point came with Qayamat Se Qayamat Tak (1988), directed by Mansoor Khan, written and produced by his father Nasir Hussain, and starring his cousin Aamir Khan with Juhi Chawla. Its blend of youthfulness, wholesome entertainment, emotional quotients and strong melodies lured family audiences back to the big screen.[35][36] It set a new template for Bollywood musical romance films that defined Hindi cinema in the 1990s.[36]

The period of Hindi cinema from the 1990s onwards is referred to as "New Bollywood" cinema,[37] linked to economic liberalisation in India during the early 1990s.[38] By the early 1990s, the pendulum had swung back toward family-centric romantic musicals. Qayamat Se Qayamat Tak was followed by blockbusters such as Maine Pyar Kiya (1989), Chandni (1989), Hum Aapke Hain Kaun (1994), Dilwale Dulhania Le Jayenge (1995), Raja Hindustani (1996), Dil To Pagal Hai (1997), Pyaar To Hona Hi Tha (1998) and Kuch Kuch Hota Hai (1998). A new generation of popular actors emerged, such as Aamir Khan, Aditya Pancholi, Ajay Devgan, Akshay Kumar, Salman Khan (Salim Khan's son), and Shahrukh Khan, and actresses such as Madhuri Dixit, Sridevi, Juhi Chawla, Meenakshi Seshadri, Manisha Koirala, Kajol, and Karisma Kapoor.[34]

Since the 1990s, the three biggest Bollywood movie stars have been the "Three Khans": Aamir Khan, Shah Rukh Khan, and Salman Khan.[39][40] Combined, they have starred in most of the top ten highest-grossing Bollywood films. The three Khans have had successful careers since the late 1980s,[39] and have dominated the Indian box office since the 1990s,[41] across three decades.[42]

Influence on Western films (2000s–present)[edit]

In the 2000s, Bollywood musicals played an instrumental role in the revival of the musical film genre in the Western world.[43] Baz Luhrmann stated that his successful musical film Moulin Rouge! (2001) was directly inspired by Bollywood musicals.[44] The film thus pays homage to India, incorporating an Indian-themed play based on the ancient Sanskrit drama The Little Clay Cart and a Bollywood-style dance sequence with a song from the film China Gate. The critical and financial success of Moulin Rouge! renewed interest in the then-moribund Western musical genre, and subsequently films such as Chicago, The Producers, Rent, Dreamgirls, Hairspray, Sweeney Todd, Across the Universe, The Phantom of the Opera, Enchanted and Mamma Mia! were produced, fuelling a renaissance of the genre.[45][43]

The Guru and The 40-Year-Old Virgin also feature Indian-style song-and-dance sequences; the Bollywood musical Lagaan (2001) was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film; two other Bollywood films Devdas (2002) and Rang De Basanti (2006) were nominated for the BAFTA Award for Best Film Not in the English Language; and Danny Boyle's Academy Award winning Slumdog Millionaire (2008) also features a Bollywood-style song-and-dance number during the film's end credits.

Spanish musical films[edit]

Spain has a history and tradition of musical films that were made independent of Hollywood influence. The first films arise during the Second Spanish Republic of the 1930s and the advent of sound films. A few zarzuelas (Spanish operetta) were even adapted as screenplays during the silent era. The beginnings of the Spanish musical were focused on romantic Spanish archetypes: Andalusian villages and landscapes, gypsys, "bandoleros", and copla and other popular folk songs included in story development. These films had even more box-office success than Hollywood premieres in Spain. The first Spanish film stars came from the musical genre: Imperio Argentina, Estrellita Castro, Florián Rey (director) and, later, Lola Flores, Sara Montiel and Carmen Sevilla. The Spanish musical started to expand and grow. Juvenile stars appear and top the box-office. Marisol, Joselito, Pili & Mili, and Rocío Dúrcal were the major figures of musical films from 1960s to 1970s. Due to Spanish transition to democracy and the rise of "Movida culture", the musical genre fell in production and box-office, only saved by Carlos Saura and his flamenco musical films.

Soviet musical film under Stalin[edit]

Unlike the musical films of Hollywood and Bollywood, popularly identified with escapism, the Soviet musical was first and foremost a form of propaganda. Vladimir Lenin said that cinema was "the most important of the arts." His successor, Joseph Stalin, also recognized the power of cinema in efficiently spreading Communist Party doctrine. Films were widely popular in the 1920s, but it was foreign cinema that dominated the Soviet filmgoing market. Films from Germany and the U.S. proved more entertaining than Soviet director Sergei Eisenstein's historical dramas.[46] By the 1930s it was clear that if the Soviet cinema was to compete with its Western counterparts, it would have to give audiences what they wanted: the glamour and fantasy they got from Hollywood.[47] The musical film, which emerged at that time, embodied the ideal combination of entertainment and official ideology.

A struggle between laughter for laughter's sake and entertainment with a clear ideological message would define the golden age of the Soviet musical of the 1930s and 1940s. Then-head of the film industry Boris Shumyatsky sought to emulate Hollywood's conveyor belt method of production, going so far as to suggest the establishment of a Soviet Hollywood.[48]

The Jolly Fellows[edit]

In 1930, the esteemed Soviet film director Sergei Eisenstein went to the United States with fellow director Grigori Aleksandrov to study Hollywood's filmmaking process. The American films greatly impacted Aleksandrov, particularly the musicals.[49] He returned in 1932, and in 1934 directed The Jolly Fellows, the first Soviet musical. The film was light on plot and focused more on the comedy and musical numbers. Party officials at first met the film with great hostility. Aleksandrov defended his work by arguing the notion of laughter for laughter's sake.[50] Finally, when Aleksandrov showed the film to Stalin, the leader decided that musicals were an effective means of spreading propaganda. Messages like the importance of collective labor and rags-to-riches stories would become the plots of most Soviet musicals.

"Movies for the Millions"[edit]

The success of The Jolly Fellows ensured a place in Soviet cinema for the musical format, but immediately Shumyatsky set strict guidelines to make sure the films promoted Communist values. Shumyatsky's decree "Movies for the Millions" demanded conventional plots, characters, and montage to successfully portray Socialist Realism (the glorification of industry and the working class) on film.[51]

The first successful blend of a social message and entertainment was Aleksandrov's Circus (1936). It starred his wife, Lyubov Orlova (an operatic singer who had also appeared in The Jolly Fellows) as an American circus performer who has to immigrate to the USSR from the U.S. because she has a mixed-race child, whom she had with a black man. Amidst the backdrop of lavish musical productions, she finally finds love and acceptance in the USSR, providing the message that racial tolerance can only be found in the Soviet Union.

The influence of Busby Berkeley's choreography on Aleksandrov's directing can be seen in the musical number leading up to the climax. Another, more obvious reference to Hollywood is the Charlie Chaplin impersonator who provides comic relief throughout the film. Four million people in Moscow and Leningrad went to see Circus during its first month in theaters.[52]

Another of Aleksandrov's more-popular films was The Bright Path (1940). This was a reworking of the fairytale Cinderella set in the contemporary Soviet Union. The Cinderella of the story was again Orlova, who by this time was the most popular star in the USSR.[53] It was a fantasy tale, but the moral of the story was that a better life comes from hard work. Whereas in Circus, the musical numbers involved dancing and spectacle, the only type of choreography in Bright Path is the movement of factory machines. The music was limited to Orlova's singing. Here, work provided the spectacle.

Ivan Pyryev[edit]

The other director of musical films was Ivan Pyryev. Unlike Aleksandrov, the focus of Pyryev's films was life on the collective farms. His films, Tractor Drivers (1939), The Swineherd and the Shepherd (1941), and his most famous, Cossacks of the Kuban (1949) all starred his wife, Marina Ladynina. Like in Aleksandrov's Bright Path, the only choreography was the work the characters were doing on film. Even the songs were about the joys of working.

Rather than having a specific message for any of his films, Pyryev promoted Stalin's slogan "life has become better, life has become more joyous."[54] Sometimes this message was in stark contrast with the reality of the time. During the filming of Cossacks of the Kuban, the Soviet Union was going through a postwar famine. In reality, the actors who were singing about a time of prosperity were hungry and malnourished.[55] The films did, however, provide escapism and optimism for the viewing public.

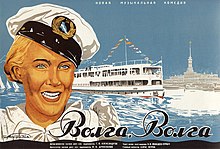

Volga-Volga[edit]

The most popular film of the brief era of Stalinist musicals was Alexandrov's 1938 film Volga-Volga. The star, again, was Lyubov Orlova and the film featured singing and dancing, having nothing to do with work. It is the most unusual of its type. The plot surrounds a love story between two individuals who want to play music. They are unrepresentative of Soviet values in that their focus is more on their music than their jobs. The gags poke fun at the local authorities and bureaucracy. There is no glorification of industry since it takes place in a small rural village. Work is not glorified either, since the plot revolves around a group of villagers using their vacation time to go on a trip up the Volga to perform in Moscow.

Volga-Volga followed the aesthetic principles of Socialist Realism rather than the ideological tenets. It became Stalin's favorite film and he gave it as a gift to President Roosevelt during WWII. It is another example of one of the films that claimed life is better. Released at the height of Stalin's purges, it provided escapism and a comforting illusion for the public.[56]

Lists of musical films[edit]

- See List of musical films by year for a list of musical films in chronological order.

- See List of Bollywood films for a list of Bollywood musical films.

- See List of films based on stage plays or musicals for a list of musical films based on theatre productions.

- See List of highest-grossing musicals for the highest-grossing musical films.

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c Kenrick, John. "History of Musical Film, 1927-30: Hollywood Learns To Sing". Musicals101.com, 2004, accessed May 17, 2010

- ^ '"Eyman, Scott. The Speed of Sound: Hollywood and the Talkie Revolution Simon & Schuster, 1997, p. 160

- ^ a b Kenrick, John. "History of Musical Film, 1927-30: Part II". Musicals101.com, 2004, accessed May 17, 2010

- ^ a b Kenrick, John. "History of Musical Film, 1930s: Part I: 'Hip, Hooray and Ballyhoo'". Musicals101.com, 2003, accessed May 17, 2010

- ^ Kenrick, John. "History of Musical Film, 1930s Part II". Musicals101.com, 2004, accessed May 17, 2010

- ^ The Big Broadcast of 1938 on imdb.con

- ^ The Big Broadcast of 1938 - Awards on imdb.com

- ^ "Build my gallows high: Joshua Oppenheimer on The Act of Killing". British Film Institute. Retrieved 2018-04-29.

- ^ Gokulsing, K. Moti; Dissanayake, Wimal (2004). Indian Popular Cinema: A Narrative of Cultural Change. Trentham Books. pp. 98–99. ISBN 978-1-85856-329-9.

- ^ Gooptu, Sharmistha (2010). Bengali Cinema: 'An Other Nation'. Routledge. p. 38. ISBN 9781136912177.

- ^ "Talking Images, 75 Years of Cinema". The Tribune. Retrieved 9 March 2013.

- ^ Before Brando, There Was Dilip Kumar, The Quint, December 11, 2015

- ^ "Unmatched innings". The Hindu. 24 January 2012. Archived from the original on 8 February 2012. Retrieved 9 January 2015.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

- ^ Sen, Raja (29 June 2011). "Readers Choice: The Greatest Actresses of all time". Rediff.com. Retrieved 19 September 2011.

- ^ K. Moti Gokulsing, K. Gokulsing, Wimal Dissanayake (2004). Indian Popular Cinema: A Narrative of Cultural Change. Trentham Books. p. 17. ISBN 978-1-85856-329-9.

- ^ Sharpe, Jenny (2005). "Gender, Nation, and Globalization in Monsoon Wedding and Dilwale Dulhania Le Jayenge". Meridians: Feminism, Race, Transnationalism. 6 (1): 58–81 [60 & 75]. doi:10.1353/mer.2005.0032.

- ^ Gooptu, Sharmistha (July 2002). "Reviewed work(s): The Cinemas of India (1896–2000) by Yves Thoraval". Economic and Political Weekly. 37 (29): 3023–4.

- ^ K. Moti Gokulsing, K. Gokulsing, Wimal Dissanayake (2004). Indian Popular Cinema: A Narrative of Cultural Change. Trentham Books. p. 18. ISBN 978-1-85856-329-9.

- ^ Khanna, Priyanka (24 February 2008). "For Bollywood, Oscar is a big yawn again". Thaindian News. Archived from the original on 30 September 2012. Retrieved 29 July 2012.

- ^ Sridharan, Tarini (25 November 2012). "Mother India, not Woman India". The Hindu. Chennai, India. Archived from the original on 6 January 2013. Retrieved 5 March 2012.

- ^ Bollywood Blockbusters: Mother India (Part 1) (Documentary). CNN-IBN. 2009. Archived from the original on 15 July 2015.

- ^ Kehr, Dave (23 August 2002). "Mother India (1957). Film in review; 'Mother India'". The New York Times. Retrieved 7 June 2012.

- ^ a b "Revisiting Prakash Mehra's Zanjeer: The film that made Amitabh Bachchan". The Indian Express. 20 June 2017.

- ^ a b Raj, Ashok (2009). Hero Vol.2. Hay House. p. 21. ISBN 9789381398036.

- ^ Ganti, Tejaswini (2004). Bollywood: A Guidebook to Popular Hindi Cinema. Psychology Press. p. 153. ISBN 9780415288545.

- ^ Chaudhuri, Diptakirti (2015). Written by Salim-Javed: The Story of Hindi Cinema's Greatest Screenwriters. Penguin Books. p. 72. ISBN 9789352140084.

- ^ Anand (7 March 2004). "On the Bollywood beat". The Hindu. Chennai, India. Retrieved 31 May 2009.

- ^ Subhash K Jha (8 April 2005). "Amit Khanna: The Man who saw 'Bollywood'". Sify. Archived from the original on 9 April 2005. Retrieved 31 May 2009.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

- ^ a b c d e Chaudhuri, Diptakirti (2015-10-01). Written by Salim-Javed: The Story of Hindi Cinema's Greatest Screenwriters. Penguin UK. p. 58. ISBN 9789352140084.

- ^ "How film-maker Nasir Husain started the trend for Bollywood masala films". Hindustan Times. 30 March 2017.

- ^ a b Kaushik Bhaumik, An Insightful Reading of Our Many Indian Identities, The Wire, 12/03/2016

- ^ Rachel Dwyer (2005). 100 Bollywood films. Lotus Collection, Roli Books. p. 14. ISBN 978-81-7436-433-3. Retrieved 6 August 2013.

- ^ Stadtman, Todd (2015). Funky Bollywood: The Wild World of 1970s Indian Action Cinema. FAB Press. ISBN 9781903254776.

- ^ a b Ahmed, Rauf. "The Present". Rediff.com. Archived from the original on 29 May 2008. Retrieved 30 June 2008.

- ^ Chintamani, Gautam (2016). Qayamat Se Qayamat Tak: The Film That Revived Hindi Cinema. HarperCollins. ISBN 9789352640980.

- ^ a b Ray, Kunal (18 December 2016). "Romancing the 1980s". The Hindu.

- ^ Sen, Meheli (2017). Haunting Bollywood: Gender, Genre, and the Supernatural in Hindi Commercial Cinema. University of Texas Press. p. 189. ISBN 9781477311585.

- ^ Joshi, Priya (2015). Bollywood's India: A Public Fantasy. Columbia University Press. p. 171. ISBN 9780231539074.

- ^ a b "The Three Khans of Bollywood - DESIblitz". 18 September 2012. Retrieved 4 July 2018.

- ^ Cain, Rob. "Are Bollywood's Three Khans The Last Of The Movie Kings?".

- ^ After Aamir, SRK, Salman, why Bollywood's next male superstar may need a decade to rise, Firstpost, 16 October 2016

- ^ "Why Aamir Khan Is The King Of Khans: Foreign Media".

- ^ a b "Hollywood/Bollywood". Public Broadcasting Service. Retrieved 12 February 2010.

- ^ "Baz Luhrmann Talks Awards and "Moulin Rouge"".

- ^ "Guide Picks – Top Movie Musicals on Video/DVD". About.com. Retrieved 15 May 2009.

- ^ Denise Youngblood. Movies for the Masses: Popular Cinema and Soviet Society in the 1920s (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992), 18

- ^ Dana Ranga. "East Side Story" (Kino International, 1997)

- ^ Richard Taylor, Derek Spring. Stalinism and Soviet Cinema (London: Routledge Inc., 1993), 75

- ^ Ranga. "East Side Story"

- ^ Andrew Horton. Inside Soviet Film Satire: Laughter with a Lash (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993), 84

- ^ Horton. Inside Soviet Film Satire, 85

- ^ Horton. Inside Soviet Film Satire, 92

- ^ Taylor, Spring. Stalinism and Soviet Cinema, 77

- ^ Joseph Stalin. Speech at the Conference of Stakhonovites (1935)

- ^ Elena Zubkova. Russia After the War: Hopes, Illusions, and Disappointments, 1945–1957 (armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe, 1998), 35

- ^ Svetlana Boym, Common Places (Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press, 1994), 200-201. ISBN 9780674146266; and Birgit Beumers, A History of Russian Cinema (Oxford: Berg, 2009). ISBN 9781845202149

Further reading[edit]

| Library resources about Musical film |

- McGee, Mark Thomas. The Rock and Roll Movie Encyclopedia of the 1950s. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland & Co., 1990. 0-89950-500-7

- Padva, Gilad. Uses of Nostalgia in Musical Politicization of Homo/Phobic Myths in Were the World Mine, The Big Gay Musical, and Zero Patience. In Padva, Gilad, Queer Nostalgia in Cinema and Pop Culture, pp. 139–172. Basingstock, UK and New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014. ISBN 978-1-137-26633-0.