Syriac language

| Syriac | |

|---|---|

| ܠܫܢܐ ܣܘܪܝܝܐ, Leššānā Suryāyā | |

Leššānā Suryāyā in written Syriac (Esṭrangelā script) | |

| Pronunciation | lɛʃˈʃɑːnɑː surˈjɑːjɑː |

| Region | Mesopotamia (ancient Iraq), northeastern Syria, southeastern Turkey, northwestern Iran,[1][2] Eastern Arabia, Fertile Crescent[3][4] |

| Era | 1st century AD; Dramatically declined as a vernacular language after the 14th century; Developed into Northeastern Neo-Aramaic and Central Neo-Aramaic languages after the 12th century.[5] |

| Syriac abjad | |

| Official status | |

Recognised minority language in | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-2 | syc Classical Syriac |

| ISO 639-3 | syc Classical Syriac |

| Glottolog | clas1252[9] |

Syriac (/ˈsɪriæk/; ܠܫܢܐ ܣܘܪܝܝܐ[a] Leššānā Suryāyā), also known as Syrian/Syriac Aramaic, Syro-Aramaic or Classical Syriac,[9][10][11] is a dialect of Middle Aramaic of the Northwest Semitic languages of the Afroasiatic family that is written in the Syriac alphabet, a derivation of the Aramaic alphabet. Having first appeared in the early first century AD in Edessa,[12] classical Syriac became a major literary language throughout the Middle East from the 4th to the 8th centuries,[13] preserved in a large body of Syriac literature. Indeed, Syriac literature comprises roughly 90% of the extant Aramaic literature.[14] Syriac was once spoken across much of the Near East as well as Anatolia and Eastern Arabia.[3][4][15] Syriac originated in Mesopotamia and eventually spread west of Iraq in which it became the lingua franca of the region during the Mesopotamian Neo-Assyrian period.[16][17]

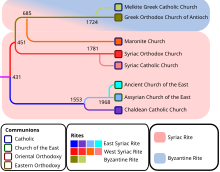

The Old Aramaic language was adopted by the Neo-Assyrian Empire (911–609 BC) when the Assyrians conquered the various Syro-Hittite states to its west. The Achaemenid Empire (546-332 BC), which rose after the fall of the Assyrian Empire, also retained Old Aramaic as its official language, and Old Aramaic remained the lingua franca of the region. During the course of the third and fourth centuries AD, the inhabitants of the region began to embrace Christianity. Because of theological differences, Syriac-speaking Christians bifurcated during the 5th century into the Church of the East, or East Syrians under Sasanian rule, and the Syriac Orthodox, or West Syrians under the Byzantine empire.[18][19] After this separation, the two groups developed distinct dialects differing primarily in the pronunciation and written symbolisation of vowels.[20] The modern, and vastly spoken, Syriac varieties today include Assyrian Neo-Aramaic, Chaldean Neo-Aramaic and Turoyo, among others, which, in turn, have their own subdialects as well.[21][22]

Along with Latin and Greek, Syriac became one of "the three most important Christian languages in the early centuries" of the Common Era.[23] From the 1st century AD, Syriac became the vehicle of Syriac Christianity and culture, and the liturgical language of the Syriac Orthodox Church, the Maronite Church, and the Church of the East, along with its descendants: the Chaldean Catholic Church, the Assyrian Church of the East, the Ancient Church of the East, the Malankara Mar Thoma Syrian Church, the Malankara Orthodox Syrian Church, the Syro-Malabar Catholic Church,[24] the Syro-Malankara Catholic Church, the Syriac Catholic Church, and the Assyrian Pentecostal Church.

Syriac Christianity and language spread throughout Asia as far as the Indian Malabar Coast[24] and Eastern China,[25] and was the medium of communication and cultural dissemination for the later Arabs and, to a lesser extent, the Parthian Empire and Sasanian Empire. Primarily a Christian medium of expression, Syriac had a fundamental cultural and literary influence on the development of Arabic,[26] which largely replaced it towards the 14th century.[5] Syriac remains the sacred language of Syriac Christianity to this day.

Geographic distribution[edit]

Syriac was the local accent of Aramaic in Edessa, and evolved under the influence of the Church of the East and the Syriac Orthodox Church into its current form. Before Arabic became the dominant language, Syriac was a major language among Christian communities in the Middle East, Central Asia and Kerala,[24] and remains so among the Syriac Christians to this day. It has been found as far afield as Hadrian's Wall in Great Britain, with inscriptions written by Assyrian and Aramean soldiers of the Roman Empire.[27]

History[edit]

The history of Syriac can be divided into three distinct periods:

- Old Aramaic, the language of the Syro-Hittite states of the Levant in the Early Iron Age, was adopted as a lingua franca beside Akkadian in the Neo-Assyrian Empire

- Middle Syriac/Middle Syriac Aramaic (ܟܬܒܢܝܐ Kṯāḇānāyā, "Literary Syriac"), which is divided into:

- Eastern Middle Syriac/Eastern Middle Syriac Aramaic (the literary and ecclesiastical language of the ethnic Syriac Christians of the Assyrian Church of the East, Chaldean Catholic Church, Syro-Malabar Catholic Church, Ancient Church of the East and Assyrian Pentecostal Church)

- Western Middle Syriac/Western Middle Syriac Aramaic (the literary and ecclesiastical language of the largely Syriac members of the Syriac Orthodox Church, Syriac Catholic Church and Maronite Church).

- "Modern Syriac"/"Modern Syriac Aramaic" is a term occasionally used to refer to the modern Neo-Aramaic languages.[28] Even if they cannot be positively identified as the direct descendants of attested Middle Syriac, they must have developed from closely related dialects belonging to the same branch of Aramaic, and the varieties spoken in Christian communities have long co-existed with and been influenced by Middle Syriac as a liturgical and literary language. In this terminology, Modern Syriac is divided into:

- Modern Western Syriac Aramaic (Turoyo and Mlahsô). Note however that these are sometimes excluded from the category of "Modern Syriac".[28]

- Modern Eastern Syriac Aramaic (Northeastern Neo-Aramaic, including Assyrian Neo-Aramaic and Chaldean Neo-Aramaic but the term usually is not used in reference to Neo-Mandaic, another variety of Eastern Aramaic spoken by the Mandaeans).

The name "Syriac", when used with no qualification, generally refers to one specific dialect of Middle Aramaic but not to Old Aramaic or to the various present-day Eastern and Central Neo-Aramaic languages descended from it or from close relatives. The modern varieties are, therefore, not discussed in this article.

Origins and spread[edit]

In 132 BC, the kingdom of Osroene was founded in Edessa and Proto-Syriac evolved in that kingdom. Many Syriac-speakers still look to Edessa as the cradle of their language.[29] There are about eighty extant early Syriac inscriptions, dated to the first three centuries AD (the earliest example of Syriac, rather than Imperial Aramaic, is in an inscription dated to AD 6, and the earliest parchment is a deed of sale dated to AD 243). All of these early examples of the language are non-Christian. As an official language, Syriac was given a relatively coherent form, style and grammar that is lacking in other Old Eastern Aramaic dialects. The Syriac language split into a western variety used by the Syriac Orthodox Churches in upper Mesopotamia and western Syria, and an eastern dialect used in the Sasanian Empire controlled east used by the Church of the East.[30]

During the establishment of the Church of the East in central-southern Iraq, speakers of Syriac split into two; those who followed the Eastern Syriac Rite and those who followed Western Syriac Rite. Syriac was the lingua franca of the entire region of Mesopotamia and the native language of the peoples of Iraq and surrounding regions until it was spread further west of the country to the entire Fertile Crescent region, as well as in parts of Eastern Arabia, becoming the dominant language for centuries, before the spread and replacement with Arabic language as the lingua franca.[31] For this reason, Mesopotamian Iraqi Arabic being an Aramaic Syriac substratum, is said to be the most Aramaic Syriac influenced dialect of Arabic,[32][33][34] sharing significant similarities in language structure, as well as having evident and stark influences from other ancient Mesopotamian languages of Iraq, such as Akkadian, Sumerian and Babylonian.[32][33]

Mesopotamian Arabic dialects developed by Iraqi Muslims, Iraqi Jews, as well as dialects by Iraqi Christians, most of whom are native ethnic Syriac speakers. Today, Syriac is the native spoken language of millions of Iraqi-Chaldo-Assyrians living in Iraq and the diaspora, and other Syriac-speaking people from Mesopotamia, such as the Mandaean people of Iraq. The dialects of Syriac spoken today include Assyrian Neo-Aramaic, Chaldean Neo-Aramaic, and Mandaic.[35][36][37]

Literary Syriac[edit]

ܛܘܼܒܲܝܗܘܿܢ ܠܐܲܝܠܹܝܢ ܕܲܕ݂ܟܹܝܢ ܒܠܸܒ̇ܗܘܿܢ܄ ܕܗܸܢ݂ܘܿܢ ܢܸܚܙܘܿܢ ܠܐܲܠܵܗܵܐ܂

Ṭūḇayhōn l-ʾaylên da-ḏḵên b-lebbhōn, d-hennōn neḥzōn l-ʾălāhā.

'Blessed are the pure in heart, for they shall see God.'

In the 3rd century, churches in Edessa began to use Syriac as the language of worship. There is evidence that the adoption of Syriac, the language of the Assyrian people, was to effect mission.[clarification needed] Much literary effort was put into the production of an authoritative translation of the Bible into Syriac, the Peshitta (ܦܫܝܛܬܐ Pšīṭtā). At the same time, Ephrem the Syrian was producing the most treasured collection of poetry and theology in the Syriac language.

In 489, many Syriac-speaking Christians living in the eastern reaches of the Roman Empire fled to the Sasanian Empire to escape persecution and growing animosity with Greek-speaking Christians.[citation needed] The Christological differences with the Church of the East led to the bitter Nestorian Schism in the Syriac-speaking world. As a result, Syriac developed distinctive western and eastern varieties. Although remaining a single language with a high level of comprehension between the varieties, the two employ distinctive variations in pronunciation and writing system, and, to a lesser degree, in vocabulary.

Western Syriac is the official language of the West Syriac Rite, practised by the Syriac Orthodox Church, the Syriac Catholic Church, the Maronite Catholic Church, the Malankara Orthodox Syrian Church, the Malabar Independent Syrian Church, the Malankara Mar Thoma Syrian Church and the Syro-Malankara Catholic Church.

Eastern Syriac is the liturgical language of the East Syriac Rite, practised in modern times by the ethnic Assyrian followers of the Assyrian Church of the East, the Assyrian Pentecostal Church, the Ancient Church of the East, the Chaldean Catholic Church, as well as the Syro-Malabar Catholic Church in India.

Syriac literature is by far the most prodigious of the various Aramaic languages. Its corpus covers poetry, prose, theology, liturgy, hymnody, history, philosophy, science, medicine and natural history. Much of this wealth remains unavailable in critical editions or modern translation.

From the 7th century onwards, Syriac gradually gave way to Arabic as the spoken language of much of the region, excepting northern Iraq. The Mongol invasions and conquests of the 13th century, and the religiously motivated massacres of Syriac Christians by Timur further contributed to the rapid decline of the language. In many places outside of Upper Mesopotamia, even in liturgy, it was replaced by Arabic.

Current status[edit]

Revivals of literary Syriac in recent times have led to some success with the creation of newspapers in written Syriac (ܟܬܒܢܝܐ Kṯāḇānāyā) similar to the use of Modern Standard Arabic has been employed since the early decades of the 20th century.[clarification needed] Modern literary Syriac has also been used not only in religious literature but also in secular genres often with Assyrian nationalistic themes.[38]

Syriac is spoken as the liturgical language of the Syriac Orthodox Church, as well as by some of its adherents.[39] Syriac has been recognised as an official minority language in Iraq.[40] It is also taught in some public schools in Iraq, the Democratic Federation of Northern Syria, Israel, Sweden,[41][42] Augsburg (Germany) and Kerala (India).

In 2014, an Assyrian nursery school could finally be opened in Yeşilköy, Istanbul[43] after waging a lawsuit against the Ministry of National Education which had denied it permission, but was required to respect non-Muslim minority rights as specified in the Treaty of Lausanne.[44]

In August 2016, the Ourhi Centre was founded by the Assyrian community in the city of Qamishli, to educate teachers in order to make Syriac an additional language to be taught in public schools in the Jazira Region of the Democratic Federation of Northern Syria,[45] which then started with the 2016/17 academic year.[46]

Grammar[edit]

Many Syriac words, like those in other Semitic languages, belong to triconsonantal roots, collations of three Syriac consonants. New words are built from these three consonants with variable vowel and consonant sets. For example, the following words belong to the root ܫܩܠ (ŠQL), to which a basic meaning of taking can be assigned:

- ܫܩܠ – šqal: "he has taken"

- ܢܫܩܘܠ – nešqol: "he will take, he was taking, he does take"

- ܫܩܘܠ – šqol: "take!"

- ܫܩܠ – šāqel: "he takes, he is taking"

- ܫܩܠ – šaqqel: "he has lifted/raised"

- ܐܫܩܠ – ʾašqel: "he has set out"

- ܫܩܠܐ – šqālā: "a taking, burden, recension, portion or syllable"

- ܫܩ̈ܠܐ – šeqlē: "takings, profits, taxes"

- ܫܩܠܘܬܐ – šaqluṯā: "a beast of burden"

- ܫܘܩܠܐ – šuqqālā: "arrogance"

Nouns[edit]

Most Syriac nouns are built from triliteral roots. Nouns carry grammatical gender (masculine or feminine), they can be either singular or plural in number (a very few can be dual) and can exist in one of three grammatical states. These states should not be confused with grammatical cases in other languages.

- The absolute state is the basic form of the noun – ܫܩ̈ܠܝܢ, šeqlin, "taxes".

- The emphatic state usually represents a definite noun – ܫܩ̈ܠܐ, šeqlē, "the taxes".

- The construct state marks a noun in relationship to another noun – ܫܩ̈ܠܝ, šeqlay, "taxes of...".

However, very quickly in the development of Classical Syriac, the emphatic state became the ordinary form of the noun, and the absolute and construct states were relegated to certain stock phrases (for example, ܒܪ ܐܢܫܐ/ܒܪܢܫܐ, bar nāšā, "man, person", literally "son of man").

In Old and early Classical Syriac, most genitive noun relationships are built using the construct state, but contrary to the genitive case, it is the head-noun which is marked by the construct state. Thus, ܫܩ̈ܠܝ ܡܠܟܘܬܐ, šeqlay malkuṯā, means "the taxes of the kingdom". Quickly, the construct relationship was abandoned and replaced by the use of the relative particle ܕ, d-, da-. Thus, the same noun phrase becomes ܫܩ̈ܠܐ ܕܡܠܟܘܬܐ, šeqlē d-malkuṯā, where both nouns are in the emphatic state. Very closely related nouns can be drawn into a closer grammatical relationship by the addition of a pronominal suffix. Thus, the phrase can be written as ܫܩ̈ܠܝܗ ܕܡܠܟܘܬܐ, šeqlêh d-malkuṯā. In this case, both nouns continue to be in the emphatic state, but the first has the suffix that makes it literally read "her taxes" ("kingdom" is feminine), and thus is "her taxes, [those] of the kingdom".

Adjectives always agree in gender and number with the nouns they modify. Adjectives are in the absolute state if they are predicative, but agree with the state of their noun if attributive. Thus, ܒܝܫܝ̈ܢ ܫܩ̈ܠܐ, bišin šeqlē, means "the taxes are evil", whereas ܫܩ̈ܠܐ ܒܝ̈ܫܐ, šeqlē ḇišē, means "evil taxes".

Verbs[edit]

Most Syriac verbs are built on triliteral roots as well. Finite verbs carry person, gender (except in the first person) and number, as well as tense and conjugation. The non-finite verb forms are the infinitive and the active and passive participles.

Syriac has only two true morphological tenses: perfect and imperfect. Whereas these tenses were originally aspectual in Aramaic, they have become a truly temporal past and future tenses respectively. The present tense is usually marked with the participle followed by the subject pronoun. However, such pronouns are usually omitted in the case of the third person. This use of the participle to mark the present tense is the most common of a number of compound tenses that can be used to express varying senses of tense and aspect.

Syriac also employs derived verb stems such as are present in other Semitic languages. These are regular modifications of the verb's root to express other changes in meaning. The first stem is the ground state, or Pəʿal (this name models the shape of the root) form of the verb, which carries the usual meaning of the word. The next is the intensive stem, or Paʿʿel, form of the verb, which usually carries an intensified meaning. The third is the extensive stem, or ʾAp̄ʿel, form of the verb, which is often causative in meaning. Each of these stems has its parallel passive conjugation: the ʾEṯpəʿel, ʾEṯpaʿʿal and ʾEttap̄ʿal respectively. To these six cardinal stems are added a few irregular stems, like the Šap̄ʿel and ʾEštap̄ʿal, which generally have an extensive meaning.

Phonology[edit]

This section does not cite any sources. (January 2009) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

Phonologically, like the other Northwest Semitic languages, Syriac has 22 consonants. The consonantal phonemes are:

| transliteration | ʾ | b | g | d | h | w | z | ḥ | ṭ | y | k | l | m | n | s | ʿ | p | ṣ | q | r | š | t |

| letter | ܐ | ܒ | ܓ | ܕ | ܗ | ܘ | ܙ | ܚ | ܛ | ܝ | ܟ | ܠ | ܡ | ܢ | ܣ | ܥ | ܦ | ܨ | ܩ | ܪ | ܫ | ܬ |

| pronunciation | [ʔ] | [b], [v] | [g], [ɣ] | [d], [ð] | [h] | [w] | [z] | [ħ] | [tˤ] | [j] | [k], [x] | [l] | [m] | [n] | [s] | [ʕ] | [p], [f] | [sˤ] | [q] | [r] | [ʃ] | [t], [θ] |

Phonetically, there is some variation in the pronunciation of Syriac in its various forms. The various Modern Eastern Aramaic vernaculars have quite different pronunciations, and these sometimes influence how the classical language is pronounced, for example, in public prayer. Classical Syriac has two major streams of pronunciation: western and eastern.

Consonants[edit]

Syriac shares with Aramaic a set of lightly-contrasted stop/fricative pairs. In different variations of a certain lexical root, a root consonant might exist in stop form in one variation and fricative form in another. In the Syriac alphabet, a single letter is used for each pair. Sometimes a dot is placed above the letter (quššāyā "strengthening"; equivalent to a dagesh in Hebrew) to mark that the stop pronunciation is required, and a dot is placed below the letter (rukkāḵā "softening") to mark that the fricative pronunciation is required. The pairs are:

- Voiced labial pair – /b/ and /v/

- Voiced velar pair – /ɡ/ and /ɣ/

- Voiced dental pair – /d/ and /ð/

- Voiceless labial pair – /p/ and /f/

- Voiceless velar pair – /k/ and /x/

- Voiceless dental pair – /t/ and /θ/

Like some Semitic languages, Syriac too has emphatic consonants, and it has three of them. These are consonants that have a coarticulation in the pharynx or slightly higher. The set consists of:

- Pharyngealized voiceless dental stop – /tˤ/

- Pharyngealized voiceless alveolar fricative – /sˤ/

- Voiceless uvular stop – /q/ (historically emphatic variant of /k/)

There are two pharyngeal fricatives, another class of consonants typically found in Semitic languages.

Syriac also has a rich array of sibilants:

- Voiced alveolar fricative – /z/

- Voiceless alveolar fricative – /s/

- Pharyngealized voiceless alveolar fricative – /sˤ/

- Voiceless postalveolar sibilant – /ʃ/

| Bilabial | Labio- dental |

Dental | Alveolar | Post- alveolar |

Palatal | Velar | Uvular | Pharyn- geal |

Glottal | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| plain | emphatic | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Nasal | m | n | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Stop | p | b | t | d | tˤ | k | ɡ | q | ʔ | |||||||||||||

| Fricative | f | v | θ | ð | s | z | sˤ | ʃ | x | ɣ | ħ | ʕ | h | |||||||||

| Approximant | w | l | j | |||||||||||||||||||

| Trill | r | |||||||||||||||||||||

Vowels[edit]

As with most Semitic languages, the vowels of Syriac are mostly subordinated to consonants. Especially in the presence of an emphatic consonant, vowels tend to become mid-centralised.

Classical Syriac had the following set of distinguishable vowels:

- Close front unrounded vowel – /i/

- Close-mid front unrounded vowel – /e/

- Open-mid front unrounded vowel – /ɛ/

- Open front unrounded vowel – /a/

- Open back unrounded vowel – /ɑ/

- Close-mid back rounded vowel – /o/

- Close back rounded vowel – /u/

In the western dialect, /ɑ/ has become /o/, and the original /o/ has merged with /u/. In eastern dialects there is more fluidity in the pronunciation of front vowels, with some speakers distinguishing five qualities of such vowels, and others only distinguishing three. Vowel length is generally not important: close vowels tend to be longer than open vowels.

The open vowels form diphthongs with the approximants /j/ and /w/. In almost all dialects, the full sets of possible diphthongs collapses into two or three actual pronunciations:

- /ɑj/ usually becomes /aj/, but the western dialect has /oj/

- /aj/, further, sometimes monophthongized to /e/

- /aw/ usually becomes /ɑw/

- /ɑw/, further, sometimes monophthongized to /o/

See also[edit]

- Corpus Scriptorum Christianorum Orientalium

- Levantine Arabic

- List of loanwords in Assyrian Neo-Aramaic

- Suriyani Malayalam

- Syriac sacral music

- Syriac studies

Notes[edit]

- ^ Classical, unvocalized spelling; with Eastern Syriac vowels: ܠܸܫܵܢܵܐ ܣܘܼܪܝܵܝܵܐ; with Western Syriac vowels: ܠܶܫܳ݁ܢܳܐ ܣܽܘܪܝܳܝܳܐ.

References[edit]

- ^ "Mesopotamian Languages — Department of Archaeology".

- ^ "BBC - History - Ancient History in depth: Mesopotamia".

- ^ a b Holes, Clive (2001). Dialect, Culture, and Society in Eastern Arabia: Glossary. pp. XXIV–XXVI. ISBN 978-9004107632.

- ^ a b Cameron, Averil (1993). The Mediterranean World in Late Antiquity. p. 185. ISBN 9781134980819.

- ^ a b Angold 2006, pp. 391

- ^ https://www.constituteproject.org/constitution/Iraq_2005.pdf?lang=en

- ^ http://www.turkmen.nl/1A_Others/minority-Iraq.pdf

- ^ "Kurdistan: Constitution of the Iraqi Kurdistan Region". Retrieved 14 April 2019.

- ^ a b Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2017). "Classical Syriac". Glottolog 3.0. Jena, Germany: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- ^ "Documentation for ISO 639 identifier: syc". ISO 639-2 Registration Authority - Library of Congress. Retrieved 2017-07-03.

Name: Classical Syriac

- ^ "Documentation for ISO 639 identifier: syc". ISO 639-3 Registration Authority - SIL International. Retrieved 2017-07-03.

Name: Classical Syriac

- ^ Cameron, Averil; Garnsey, Peter (1998). The Cambridge Ancient History. 13. p. 708. ISBN 9780521302005.

- ^ Beyer, Klaus (1986). The Aramaic Language: its distribution and subdivisions. John F. Healey (trans.). Göttingen: Vandenhoeck und Ruprecht. p. 44. ISBN 978-3-525-53573-8.

- ^ Tannous, Jack (2010). Syria Between Byzantium and Islam (phd). Princeton University. p. 1.

- ^ Smart, J R (2013). Tradition and Modernity in Arabic Language and Literature. p. 253. ISBN 9781136788123.

- ^ Studies in Neo-Aramaic. Heinrichs, Wolfhart. Atlanta, Ga.: Scholars Press. 1990. ISBN 978-1555404307. OCLC 20670754.CS1 maint: others (link)

- ^ The semitic languages : an international handbook. Weninger, Stefan., Khan, Geoffrey., Streck, Michael P., Watson, Janet C. E. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton. 2011. p. 652. ISBN 9783110251586. OCLC 772845156.CS1 maint: others (link)

- ^ Beyer, Klaus; John F. Healey (trans.) (1986). The Aramaic Language: its distribution and subdivisions. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck und Ruprecht. p. 44. ISBN 3-525-53573-2.

- ^ Bae, C. Aramaic as a Lingua Franca During the Persian Empire (538-333 BCE). Journal of Universal Language. March 2004, 1-20.

- ^ Maclean, Arthur John (1895). Grammar of the dialects of vernacular Syriac: as spoken by the Eastern Syrians of Kurdistan, north-west Persia, and the Plain of Mosul: with notices of the vernacular of the Jews of Azerbaijan and of Zakhu near Mosul. Cambridge University Press, London.

- ^ Avenery, Iddo, The Aramaic Dialect of the Jews of Zakho. The Israel academy of Science and Humanities 1988.

- ^ Heinrichs, Wolfhart (ed.) (1990). Studies in Neo-Aramaic. Scholars Press: Atlanta, Georgia. ISBN 1-55540-430-8.

- ^ Wilken, Robert Louis (2012-11-27). The First Thousand Years: A Global History of Christianity. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. p. 26. ISBN 978-0-300-11884-1.

- ^ a b c "City Youth Learn Dying Language, Preserve It". The New Indian Express. May 9, 2016. Retrieved May 9, 2016.

- ^ Ji, Jingyi (2007). Encounters Between Chinese Culture and Christianity: A Hermeneutical Perspective. LIT Verlag Münster. p. 41. ISBN 978-3-8258-0709-2.

- ^ Beeston, Alfred Felix Landon (1983). Arabic literature to the end of the Umayyad period. Cambridge University Press. p. 497. ISBN 978-0-521-24015-4.

- ^ Higgins, Charlotte (13 October 2009). "When Syrians, Algerians and Iraqis patrolled Hadrian's Wall". The Guardian.

- ^ a b Lipiński, Edward Lipiński (2001). Semitic Languages: Outline of a Comparative Grammar. Peeters Publishers. p. 70. ISBN 978-90-429-0815-4.

- ^ Drijvers, H. J. W. (1980). Cults and beliefs at Edessa. Brill Archive. p. 1. ISBN 978-90-04-06050-0.

- ^ Stefan Weninger (2011). The Semitic Languages: An International Handbook. p. 652. ISBN 9783110251586.

- ^ Humanism, Culture, and Language in the Near East : Studies in Honor of Georg Krotkoff. Krotkoff, Georg., Afsaruddin, Asma, 1958-, Zahniser, A. H. Mathias, 1938-. Winona Lake, Ind.: Eisenbrauns. 1997. ISBN 9781575065083. OCLC 747412055.CS1 maint: others (link)

- ^ a b "LANGUAGES OF IRAQ: ANCIENT AND MODERN p. 95" (PDF).

- ^ a b Sanchez, Francisco del Rio. ""Influences of Aramaic on dialectal Arabic", in: Archaism and Innovation in the Semitic Languages. Selected papers". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - ^ Smart, J. R.; Smart, J. R. (2013-12-16). Tradition and modernity in Arabic language and literature. Smart, J. R., Shaban Memorial Conference (2nd : 1994 : University of Exeter). Richmond, Surrey, U.K. ISBN 9781136788123. OCLC 865579151.

- ^ Donabed, Sargon (2015-02-01). Reforging a Forgotten History: Iraq and the Assyrians in the Twentieth Century. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 9780748686056.

- ^ Muller-Kessler, Christa (July 2003). "Aramaic k, lyk and Iraqi Arabic aku, maku: The Mesopotamian Particles of Existence". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 123 (3): 641–646. doi:10.2307/3217756. JSTOR 3217756.

- ^ "Minorities of IRAQ: EU Research Service" (PDF).

- ^ Kiraz, George. "Kthobonoyo Syriac: Some Observations and Remarks". Hugoye: Journal of Syriac Studies. Beth Mardutho: The Syriac Institute and Institute of Christian Oriental Research at The Catholic University of America. Archived from the original on 30 November 2011. Retrieved 30 September 2011.

- ^ Concise Encyclopedia of Languages of the World. Elsevier. 6 April 2010. pp. 58–. ISBN 978-0-08-087775-4.

- ^ Anbori, Abbas. "The Comprehensive Policy to Manage the Ethnic Languages in Iraq" (PDF): 4–5. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - ^ Dorit, Shilo (1 April 2010). "The Ben Yehudas of Aramaic". Haaretz. Retrieved 30 September 2011.

- ^ "Syriac... a language struggling to survive". Voices of Iraq. 28 December 2007. Archived from the original on 30 March 2012. Retrieved 30 September 2011.

- ^ Assyrian School Welcomes Students in Istanbul, Marking a New Beginning

- ^ Turkey Denies Request to Open Assyrian-Language Kindergarten Archived 2014-11-04 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Syriac Christians revive ancient language despite war". ARA News. 2016-08-19. Retrieved 2016-08-19.

- ^ "Hassakeh: Syriac Language to Be Taught in PYD-controlled Schools". The Syrian Observer. 3 October 2016. Retrieved 2016-10-05.

Bibliography[edit]

- Journal of Sacred Literature, New Series [Series 4] vol. 2 (1863) pp. 75–87, The Syriac Language and Literature

- Beyer, Klaus (1986). The Aramaic language: its distribution and subdivisions. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck und Ruprecht. ISBN 3-525-53573-2.

- Brock, Sebastian (2006). An Introduction to Syriac Studies. Piscataway, NJ: Gorgias Press. ISBN 1-59333-349-8.

- Brockelmann, Carl (1895). Lexicon Syriacum. Berlin: Reuther & Reichard; Edinburgh: T. & T. Clark.

- Ciancaglini, Claudia A. (2006). "SYRIAC LANGUAGE i. IRANIAN LOANWORDS IN SYRIAC". Encyclopaedia Iranica.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Healey, John F (1980). First studies in Syriac. University of Birmingham/Sheffield Academic Press. ISBN 0-7044-0390-0.

- Maclean, Arthur John (2003). Grammar of the dialects of vernacular Syriac: as spoken by the Eastern Syrians of Kurdistan, north-west Persia, and the Plain of Mosul: with notices of the vernacular of the Jews of Azerbaijan and of Zakhu near Mosul. Gorgias Press. ISBN 1-59333-018-9.

- Nöldeke, Theodor and Julius Euting (1880) Kurzgefasste syrische Grammatik. Leipzig: T.O. Weigel. [translated to English as Compendious Syriac Grammar, by James A. Crichton. London: Williams & Norgate 1904. 2003 edition: ISBN 1-57506-050-7].

- Angold, Michael (2006), O’Mahony, Anthony (ed.), Cambridge History of Christianity: Volume 5, Eastern Christianity, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0521811132.

- Payne Smith, Jessie (Ed.) (1903). A compendious Syriac dictionary founded upon the Thesaurus Syriacus of Robert Payne Smith. Oxford University Press, reprinted in 1998 by Eisenbrauns. ISBN 1-57506-032-9.

- Robinson, Theodore Henry (1915). Paradigms and exercises in Syriac grammar. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-926129-6.

- Rudder, Joshua. Learn to Write Aramaic: A Step-by-Step Approach to the Historical & Modern Scripts. n.p.: CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2011. 220 pp. ISBN 978-1461021421 Includes the Estrangela (pp. 59–113), Madnhaya (pp. 191–206), and the Western Serto (pp. 173–190) scripts.

- Syriac traditional pronunciation

External links[edit]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Syriac language. |

| Aramaic edition of Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia |

- Aramaic Dictionary (lexicon and concordance)

- Syriac at ScriptSource.com

- The Comprehensive Aramaic Lexicon

- Syriac Studies Reference Library, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University

- . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.

- Leshono Suryoyo - Die traditionelle Aussprache des Westsyrischen - The traditional pronunciation of Western Syriac