Ancient Egyptian conception of the soul

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

(Learn how and when to remove this template message)

|

| Part of a series on |

| Ancient Egyptian religion |

|---|

|

|

Beliefs |

|

Practices |

|

Locations |

|

|

Related religions |

|

|

The ancient Egyptians believed that a soul (kꜣ/bꜣ; Egypt. pron. ka/ba) was made up of many parts. In addition to these components of the soul, there was the human body (called the ḥꜥ, occasionally a plural ḥꜥw, meaning approximately "sum of bodily parts").

According to ancient Egyptian creation myths, the god Atum created the world out of chaos, utilizing his own magic (ḥkꜣ).[1] Because the earth was created with magic, Egyptians believed that the world was imbued with magic and so was every living thing upon it. When humans were created, that magic took the form of the soul, an eternal force which resided in and with every human being. The concept of the soul and the parts which encompass it has varied from the Old Kingdom to the New Kingdom, at times changing from one dynasty to another, from five parts to more. Most ancient Egyptian funerary texts reference numerous parts of the soul: the ẖt (Middle Egyptian /ˈçuːwaʔ/, Coptic ϩⲏ) "physical body", the sꜥḥ "spiritual body", the rn (/ɾin/, Coptic ⲣⲁⲛ or ⲗⲉⲛ) "name, identity", the bꜣ "personality", the kꜣ (/kuʔ/, Old Egyptian /kuʁ/) "double", the jb (/jib/, Coptic ⲉⲡ) "heart", the šwt "shadow", the sḫm (/saːχam/) "power, form", and the ꜣḫ (/ʁi:χu/, Coptic ⲓϧ), the combined spirits of a dead person that has successfully completed its transition to the afterlife.[2] Rosalie David, an Egyptologist at the University of Manchester, explains the many facets of the soul as follows:

The Egyptians believed that the human personality had many facets—a concept that was probably developed early in the Old Kingdom. In life, the person was a complete entity, but if he had led a virtuous life, he could also have access to a multiplicity of forms that could be used in the next world. In some instances, these forms could be employed to help those whom the deceased wished to support or, alternately, to take revenge on his enemies.[3]

ẖt (physical)[edit]

The ẖt, or physical form, had to exist for the soul (kꜣ/bꜣ) to have intelligence or the chance to be judged by the guardians of the underworld. Therefore, it was necessary for the body to be preserved as efficiently and completely as possible and for the burial chamber to be as personalized as it could be, with paintings and statuary showing scenes and triumphs from the deceased's life. In the Old Kingdom, only the pharaoh was granted mummification and, thus, a chance at an eternal and fulfilling afterlife. However, by the Middle Kingdom, all dead were afforded the opportunity.[4] Herodotus, an ancient Greek scholar, observed that grieving families were given a choice as to the type and or quality of the mummification they preferred: "The best and most expensive kind is said to represent [Osiris], the next best is somewhat inferior and cheaper, while the third is cheapest of all."[5]

Because the state of the body was tied so closely with the quality of the afterlife, by the time of the Middle Kingdom, not only were the burial chambers painted with depictions of favourite pastimes and great accomplishments of the dead, but there were also small figurines (ushabtis) of servants, slaves, and guards (and, in some cases beloved pets) included in the tombs, to serve the deceased in the afterlife.[6] However, an eternal existence in the afterlife was, by no means, assured.

Before a person could be judged by the gods, they had to be "awakened" through a series of funerary rites designed to reanimate their mummified remains in the afterlife. The main ceremony, the opening of the mouth ceremony, is best depicted within Pharaoh Sety I's tomb. All along the walls and statuary inside the tomb are reliefs and paintings of priests performing the sacred rituals and, below the painted images, the text of the liturgy for opening of the mouth can be found.[7] This ritual which, presumably, would have been performed during interment, was meant to reanimate each section of the body: brain, head, limbs, etc. so that the spiritual body would be able to move in the afterlife.

sꜥḥ (spiritual body)[edit]

If all the rites, ceremonies, and preservation rituals for the ẖt were observed correctly, and the deceased was found worthy (by Osiris and the gods of the underworld) of passing through into the afterlife, the sꜥḥ (or spiritual representation of the physical body) forms. This spiritual body was then able to interact with the many entities extant in the afterlife. As a part of the larger construct, the ꜣḫ, the sꜥḥ was sometimes seen as an avenging spirit which would return from the underworld to seek revenge on those who had wronged the spirit in life. A well-known example was found in a tomb from the Middle Kingdom in which a man leaves a letter to his late wife who, it can be supposed, is haunting him:

What wicked thing have I done to thee that I should have come to this evil pass? What have I done to thee? But what thou hast done to me is to have laid hands on me although I had nothing wicked to thee. From the time I lived with thee as thy husband down to today, what have I done to thee that I need hide? When thou didst sicken of the illness which thou hadst, I caused a master-physician to be fetched…I spent eight months without eating and drinking like a man. I wept exceedingly together with my household in front of my street-quarter. I gave linen clothes to wrap thee and left no benefit undone that had to be performed for thee. And now, behold, I have spent three years alone without entering into a house, though it is not right that one like me should have to do it. This have I done for thy sake. But, behold, thou dost not know good from bad.[8]

jb (heart)[edit]

| ||

| jb (F34) "heart" in hieroglyphs |

|---|

An important part of the Egyptian soul was thought to be the jb, or heart. The heart[9] was believed to be formed from one drop of blood from the heart of the child's mother, taken at conception.[citation needed] To ancient Egyptians, the heart was the seat of emotion, thought, will and intention, evidenced by the many expressions in the Egyptian language which incorporate the word jb. Unlike in English, when ancient Egyptians referenced the jb they generally meant the physical heart as opposed to a metaphorical heart. However, ancient Egyptians usually made no distinction between the mind and the heart with regard to emotion or thought. The two were synonymous.

In the Egyptian religion, the heart was the key to the afterlife. It was essential to surviving death in the nether world, where it gave evidence for, or against, its possessor. Like the physical body (ẖt), the heart was a necessary part of judgement in the afterlife and it was to be carefully preserved and stored within the mummified body with a heart scarab carefully secured to the body above it to prevent it from telling tales. According to the Text of the Book of Breathings,

[They drag Osiris in]to the Pool of Khonsu, ... and likewise [the Osirism Hor, justified] born of Taikhebyt, justified ... after he has grasped his heart. They bury ... the Book of Breathings which [Isis] made, which ... is written on both its inside and outside, (wrapped) in royal linen, and it is placed [under] the ... left arm near his heart.[10]

It was thought that the heart was examined by Anubis and the deities during the Weighing of the Heart ceremony. If the heart weighed more than the feather of Maat, it was immediately consumed by the monster Ammit, and the soul became eternally restless.

kꜣ / KA "double"[edit]

| ||

| kꜣ (D28) in hieroglyphs |

|---|

The kꜣ : 𓂓, was the Egyptian concept of vital essence, which distinguishes the difference between a living and a dead person, with death occurring when the kꜣ left the body. The Egyptians believed that Khnum created the bodies of children on a potter's wheel and inserted them into their mothers' bodies. Depending on the region, Egyptians believed that Heqet or Meskhenet was the creator of each person's kꜣ, breathing it into them at the instant of their birth as the part of their soul that made them be alive. This resembles the concept of spirit in other religions.

The Egyptians also believed that the kꜣ was sustained through food and drink. For this reason food and drink offerings were presented to the dead, although it was the kꜣw within the offerings that was consumed, not the physical aspect. In the Middle kingdom a form of offering tray known as a Soul house was developed to facilitate this.[11][12] The kꜣ was often represented in Egyptian iconography as a second image of the king, leading earlier works to attempt to translate kꜣ as double.

In the Old Kingdom private tombs, artwork depicted a "doubleworld" with essential people and objects for the owner of the ka. As Ancient Orient Curator Andrey Bolshakov explains: "The notion of the ka was a dominating concept of the next life in the Old Kingdom. In a less pure form, it lived into the Middle Kingdom, and lost much of its importance in the New Kingdom, although the ka always remained the recipient of offerings."[13]

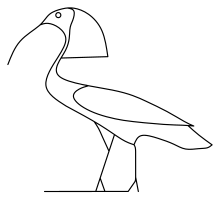

bꜣ / ba (personality)[edit]

| ||

| bꜣ (G29) in hieroglyphs |

|---|

| ||

| bꜣ (G53) in hieroglyphs |

|---|

The bꜣ (Egyptological pronunciation: ba) was everything that makes an individual unique, similar to the notion of 'personality'. In this sense, inanimate objects could also have a bꜣ, a unique character, and indeed Old Kingdom pyramids often were called the bꜣ of their owner. The bꜣ is an aspect of a person that the Egyptians believed would live after the body died, and it is sometimes depicted as a human-headed bird flying out of the tomb to join with the kꜣ in the afterlife.[14]

In the Coffin Texts, one form of the bꜣ that comes into existence after death is corporeal—eating, drinking and copulating. Egyptologist Louis Vico Žabkar argues that the bꜣ is not merely a part of the person but is the person himself, unlike the soul in Greek, or late Judaic, Christian or Muslim thought. The idea of a purely immaterial existence was so foreign to Egyptian thought that when Christianity spread in Egypt, they borrowed the Greek word ψυχή psychē to describe the concept of soul instead of the term bꜣ. Žabkar concludes that so particular was the concept of the bꜣ to ancient Egyptian thought that it ought not to be translated but instead the concept be footnoted or parenthetically explained as one of the modes of existence for a person.[15]

In another mode of existence the bꜣ of the deceased is depicted in the Book of the Dead returning to the mummy and participating in life outside the tomb in non-corporeal form, echoing the solar theology of Ra uniting with Osiris each night.[16]

The word bꜣw (baw), plural of the word bꜣ, meant something similar to "impressiveness", "power", and "reputation", particularly of a deity. When a deity intervened in human affairs, it was said that the bꜣw of the deity were at work.[17]

šwt (shadow)[edit]

A person's shadow or silhouette, šwt, is always present. Because of this, Egyptians surmised that a shadow contains something of the person it represents. Through this association, statues of people and deities were sometimes referred to as shadows.

The shadow was also representative to Egyptians of a figure of death, or servant of Anubis, and was depicted graphically as a small human figure painted completely black. In some cases the šwt represented the impact a person had on the earth. Sometimes people (usually pharaohs) had a shadow box in which part of their šwt was stored.[18]

In a commentary to The Egyptian Book of the Dead (BD), Egyptologist Ogden Goelet, Jr. discusses the forms of the shadow: "In many BD papyri and tombs the deceased is depicted emerging from the tomb by day in shadow form, a thin, black, featureless silhouette of a person. The person in this form is, as we would put it, a mere shadow of his former existence, yet nonetheless still existing. Another form the shadow assumes in the BD, especially in connection with gods, is an ostrich-feather sun-shade, an object which would create a shadow."[19]

sḫm (form)[edit]

Little is known about the Egyptian interpretation of this portion of the soul. Many scholars define sḫm as the living force or life-force of the soul which exists in the afterlife after all judgement has been passed. However, sḫm is also defined in a Book of the Dead as the "power" and as a place within which Horus and Osiris dwell in the underworld.[2]

rn / Ren (name)[edit]

As a part of the soul, a person's rn (or Ren) (rn 'name') was given to them at birth and the Egyptians believed that it would live for as long as that name was spoken, which explains why efforts were made to protect it and the practice of placing it in numerous writings. It is a person's identity, their experiences, and their entire life's worth of memories. For example, part of the Book of Breathings, a derivative of the Book of the Dead, was a means to ensure the survival of the name. A cartouche (magical rope) often was used to surround the name and protect it. Conversely, the names of deceased enemies of the state, such as Akhenaten, were hacked out of monuments in a form of damnatio memoriae. Sometimes, however, they were removed in order to make room for the economical insertion of the name of a successor, without having to build another monument. The greater the number of places a name was used, the greater the possibility it would survive to be read and spoken.

ꜣḫ / Akh[edit]

The ꜣḫ "(magically) effective one"[14] was a concept of the dead that varied over the long history of ancient Egyptian belief. Relative to the afterlife, akh represented the deceased, who was transfigured and often identified with light.[20]

It was associated with thought, but not as an action of the mind; rather, it was intellect as a living entity. The ꜣḫ also played a role in the afterlife. Following the death of the ẖt (physical body), the bꜣ and kꜣ were reunited to reanimate the ꜣḫ.[21][full citation needed] The reanimation of the ꜣḫ was only possible if the proper funeral rites were executed and followed by constant offerings. The ritual was termed s-ꜣḫ "make (a dead person) into an (living) ꜣḫ". In this sense, it even developed into a sort of ghost or roaming dead being (when the tomb was not in order any more) during the Twentieth Dynasty. An ꜣḫ could do either harm or good to persons still living, depending on the circumstances, causing e.g., nightmares, feelings of guilt, sickness, etc. It could be invoked by prayers or written letters left in the tomb's offering chapel also in order to help living family members, e.g., by intervening in disputes, by making an appeal to other dead persons or deities with any authority to influence things on earth for the better, but also to inflict punishments.

The separation of ꜣḫ and the unification of kꜣ and bꜣ were brought about after death by having the proper offerings made and knowing the proper, efficacious spell, but there was an attendant risk of dying again. Egyptian funerary literature (such as the Coffin Texts and the Book of the Dead) were intended to aid the deceased in "not dying a second time" and to aid in becoming an ꜣḫ.

Relationships[edit]

Ancient Egyptians believed that death occurs when a person's kꜣ leaves the body. Ceremonies conducted by priests after death, including the "opening of the mouth (wp r)", aimed not only to restore a person's physical abilities in death, but also to release a Ba's attachment to the body. This allowed the bꜣ to be united with the kꜣ in the afterlife, creating an entity known as an ꜣḫ.

Egyptians conceived of an afterlife as quite similar to normal physical existence – but with a difference. The model for this new existence was the journey of the Sun. At night the Sun descended into the Duat or "underworld". Eventually the Sun meets the body of the mummified Osiris. Osiris and the Sun, re-energized by each other, rise to new life for another day. For the deceased, their body and their tomb were their personal Osiris and a personal Duat. For this reason they are often addressed as "Osiris". For this process to work, some sort of bodily preservation was required, to allow the bꜣ to return during the night, and to rise to new life in the morning. However, the complete ꜣḫs were also thought to appear as stars.[22] Until the Late Period, non-royal Egyptians did not expect to unite with the Sun deity, it being reserved for the royals.[23]

The Book of the Dead, the collection of spells which aided a person in the afterlife, had the Egyptian name of the Book of going forth by day. They helped people avoid the perils of the afterlife and also aided their existence, containing spells to ensure "not dying a second time in the underworld", and to "grant memory always" to a person. In the Egyptian religion it was possible to die in the afterlife and this death was permanent.

The tomb of Paheri, an Eighteenth dynasty nomarch of Nekhen, has an eloquent description of this existence, and is translated by James Peter Allen as:

Your life happening again, without your ba being kept away from your divine corpse, with your ba being together with the akh ... You shall emerge each day and return each evening. A lamp will be lit for you in the night until the sunlight shines forth on your breast. You shall be told: "Welcome, welcome, into this your house of the living!"[14]

Notes[edit]

- ^ Pinch, Geraldine (2004). Egyptian Mythology: A Guide to the Gods, Goddesses, and Traditions of Ancient Egypt. Oxford University Press.

- ^ a b BUDGE, E. A. WALLIS. THE BOOK OF THE DEAD The Papyrus of Ani IN THE BRITISH MUSEUM. THE EGYPTIAN TEXT WITH INTERLINEAR TRANSLITERATION AND TRANSLATION, A RUNNING TRANSLATION, INTRODUCTION, ETC. https://www.sacred-texts.com/egy/ebod/index.htm: British Museum.

- ^ David, Rosalie (2003). Religion and Magic in Ancient Egypt. Penguin Books. p. 116.

- ^ Ikram, Salima (2003). Death and Burial in Ancient Egypt. Longman. ISBN 978-0582772168.

- ^ Nardo, Don (2004). Exploring Cultural History - Living in Ancient Egypt. Thomson/Gale. p. 110.

- ^ Miniaci, Gianluca (2014). "THE CASE OF THE THIRD INTERMEDIATE PERIOD 'SHABTI-MAKER (?) OF THE AMUNDOMAIN' DIAMUN / PADIAMUN AND THE CHANGE IN CONCEPTION OF SHABTISTATUETTES". The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology. 100: 245–273. JSTOR 24644973.

- ^ Mojsov, Bojana (Winter 2002). "The Ancient Egyptian Underworld in the Tomb of Sety I: Sacred Books of Eternal Life". The Massachusetts Review. 42 (4): 489–506. JSTOR 25091798.

- ^ Nardo, Don. Living in Ancient Egypt. Thomson/Gale. p. 39.

- ^ "Ib | ancient Egyptian religion". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2018-03-17.

- ^ Rhodes, Michael (2015). Translation of the Book of Breathings. Brigham young University.

- ^ "soul house". British Museum Collection online. British Museum. Retrieved 30 November 2018.

- ^ "Soul-houses". Digital Egypt for Universities. University College London. 2002. Retrieved 21 October 2018.

- ^ The ancient gods speak : a guide to Egyptian religion. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press. 2002. p. 181. ISBN 019515401-0.

- ^ a b c Allen, James W. (2000). Middle Egyptian : An Introduction to the Language and Culture of Hieroglyphs. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-77483-3.

- ^ Žabkar, Louis V. (1968). A Study of the Ba Concept In Ancient Egyptian Texts (PDF). University of Chicago Press. pp. 162–163. LCCN 68-55393.

- ^ Oxford Guide: The Essential Guide to Egyptian Mythology, James P. Allen, p. 28, Berkley, 2003, ISBN 0-425-19096-X

- ^ Borghouts, Joris Frans (1982). ""Divine Intervention in Ancient Egypt and Its Manifestation (bꜣw)" In Gleanings from Deir el-Medîna, edited by Robert Johannes Demarée and Jacobus Johannes Janssen". Egyptologische Uitgaven, Leiden: Nederlands Instituut Voor Het Nabije Oosten: 1–70.

- ^ "Monuments and the Parts of the Soul". Erenow. Retrieved 5 February 2019.

- ^ Goelet, Ogden, Jr. (1994). The Egyptian Book of the dead: the Book of going forth by day: being the Papyrus of Ani (royal scribe of the divine offerings), written and illustrated circa 1250 B.C.E., by scribes and artists unknown, including the balance of chapters of the books of the dead known as the Theban recension, compiled from ancient texts, dating back to the roots of Egyptian civilization (1st ed.). Chronicle Books. p. 152. ISBN 0811807673.

- ^ The ancient gods speak : a guide to Egyptian religion. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press. 2002. p. 7. ISBN 0195154010.

- ^ Egyptology online, 2009

- ^ Frankfort, Henri (2011). Ancient Egyptian Religion: An Interpretation. Courier Corporation. p. 100. ISBN 978-0-486-41138-5.

- ^ 26th Dynasty stela description Archived 2007-09-29 at the Wayback Machine from Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna

References[edit]

- Egyptology online (2001), The concept of the afterlife, archived from the original on 2008-04-21, retrieved 2009-01-01

Further reading[edit]

- Allen, James Paul. 2001. "Ba". In The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, edited by Donald Bruce Redford. Vol. 1 of 3 vols. Oxford, New York, and Cairo: Oxford University Press and The American University in Cairo Press. 161–162.

- Allen, James P. 2000. "Middle Egyptian: An Introduction to the Language and Culture of Hieroglyphs", Cambridge University Press.

- Borghouts, Joris Frans. 1982. "Divine Intervention in Ancient Egypt and Its Manifestation (b3w)". In Gleanings from Deir el-Medîna, edited by Robert Johannes Demarée and Jacobus Johannes Janssen. Egyptologische Uitgaven 1. Leiden: Nederlands Instituut voor het Nabije Oosten. 1–70.

- Borioni, Giacomo C. 2005. "Der Ka aus religionswissenschaftlicher Sicht", Veröffentlichungen der Institute für Afrikanistik und Ägyptologie der Universität Wien.

- Burroughs, William S. 1987. "The Western Lands", Viking Press. (fiction).

- Friedman, Florence Margaret Dunn. 1981. On the Meaning of Akh (3ḫ) in Egyptian Mortuary Texts. Doctoral dissertation; Waltham: Brandeis University, Department of Classical and Oriental Studies.

- ———. 2001. "Akh". In The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, edited by Donald Bruce Redford. Vol. 1 of 3 vols. Oxford, New York, and Cairo: Oxford University Press and The American University in Cairo Press. 47–48.

- Žabkar, Louis Vico. 1968. A Study of the Ba Concept in Ancient Egyptian Texts. Studies in Ancient Oriental Civilization 34. Chicago: University of Chicago Press