Book of Isaiah

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tanakh (Judaism) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Old Testament (Christianity) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bible portal | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Book of Isaiah (Hebrew: ספר ישעיהו, IPA: [sɛ.fɛr jə.ʃaʕ.ˈjɑː.hu]) is the first of the Latter Prophets in the Hebrew Bible and the first of the Major Prophets in the Christian Old Testament.[1] It is identified by a superscription as the words of the 8th-century BCE prophet Isaiah ben Amoz, but there is extensive evidence that much of it was composed during the Babylonian captivity and later.[2] After Johann Christoph Döderlein suggested in 1775 that the book contained the works of two prophets separated by more than a century,[3] Bernhard Duhm originated the view, held as a consensus through most of the 20th century, that the book comprises three separate collections of oracles:[4][5] Proto-Isaiah (chapters 1–39), containing the words of the 8th century prophet Isaiah; Deutero-Isaiah (chapters 40–55), the work of an anonymous 6th-century BCE author writing during the Exile; and Trito-Isaiah (chapters 56–66), composed after the return from Exile.[6] While virtually no scholars today attribute the entire book, or even most of it, to one person,[4] the book's essential unity has become a focus in more recent research. Isaiah 1–33 promises judgment and restoration for Judah, Jerusalem and the nations, and chapters 34–66 presume that judgment has been pronounced and restoration follows soon.[7] It can thus be read as an extended meditation on the destiny of Jerusalem into and after the Exile.[8]

The Deutero-Isaian part of the book describes how God will make Jerusalem the centre of his worldwide rule through a royal saviour (a messiah) who will destroy her oppressor (Babylon); this messiah is the Persian king Cyrus the Great, who is merely the agent who brings about Yahweh's kingship.[9] Isaiah speaks out against corrupt leaders and for the disadvantaged, and roots righteousness in God's holiness rather than in Israel's covenant.[10] Isaiah 44:6 contains the first clear statement of monotheism: "I am the first and I am the last; beside me there is no God".[11] This model of monotheism became the defining characteristic of post-Exilic Judaism, and the basis for Christianity and Islam.[12]

Isaiah was one of the most popular works among Jews in the Second Temple period (c. 515 BCE – 70 CE).[13] In Christian circles, it was held in such high regard as to be called "the Fifth Gospel",[14] and its influence extends beyond Christianity to English literature and to Western culture in general, from the libretto of Handel's Messiah to a host of such everyday phrases as "swords into ploughshares" and "voice in the wilderness".[15]

Structure[edit]

Scholarly consensus through most of the 20th century saw three separate collections of oracles in the book of Isaiah.[4] A typical outline based on this understanding of the book sees its underlying structure in terms of the identification of historical figures who might have been their authors:[17]

- 1–39: Proto-Isaiah, containing the words of the original Isaiah;

- 40–55: Deutero-Isaiah, the work of an anonymous Exilic author;

- 56–66: Trito-Isaiah, an anthology of about twelve passages.[18]

While one part of the consensus still holds – virtually no contemporary scholar maintains that the entire book, or even most of it, was written by one person – this perception of Isaiah as made up of three rather distinct sections underwent a radical challenge in the last quarter of the 20th century.[19] The newer approach looks at the book in terms of its literary and formal characteristics, rather than authors, and sees in it a two-part structure divided between chapters 33 and 34:[20]

- 1–33: Warnings of judgment and promises of subsequent restoration for Jerusalem, Judah and the nations;

- 34–66: Judgment has already taken place and restoration is at hand.

Summary[edit]

Seeing Isaiah as a two-part book (chapters 1–33 and 34–66) with an overarching theme leads to a summary of its contents like the following:[9]

- The book opens by setting out the themes of judgment and subsequent restoration for the righteous. God has a plan which will be realised on the "Day of Yahweh", when Jerusalem will become the centre of his worldwide rule. On that day all the nations of the world will come to Zion (Jerusalem) for instruction, but first the city must be punished and cleansed of evil. Israel is invited to join in this plan. Chapters 5–12 explain the significance of the Assyrian judgment against Israel: righteous rule by the Davidic king will follow after the arrogant Assyrian monarch is brought down. Chapters 13–27 announce the preparation of the nations for Yahweh's world rule; chapters 28–33 announce that a royal saviour (a messiah) will emerge in the aftermath of Jerusalem's punishment and the destruction of her oppressor.

- The oppressor (now identified as Babylon rather than Assyria) is about to fall. Chapters 34–35 tell how Yahweh will return the redeemed exiles to Jerusalem. Chapters 36–39 tell of the faithfulness of king Hezekiah to Yahweh during the Assyrian siege as a model for the restored community. Chapters 40–54 state that the restoration of Zion is taking place because Yahweh, the creator of the universe, has designated the Persian king Cyrus the Great as the promised messiah and temple-builder. Chapters 55–66 are an exhortation to Israel to keep the covenant. God's eternal promise to David is now made to the people of Israel/Judah at large. The book ends by enjoining righteousness as the final stages of God's plan come to pass, including the pilgrimage of the nations to Zion and the realisation of Yahweh's kingship.

The older understanding of this book as three fairly discrete sections attributable to identifiable authors leads to a more atomised picture of its contents, as in this example:

- Proto-Isaiah/First Isaiah (chapters 1–39):[21]

- 1–12: Oracles against Judah mostly from Isaiah's early years;

- 13–23: Oracles against foreign nations from his middle years;

- 24–27: The "Isaiah Apocalypse", added at a much later date;

- 28–33: Oracles from Isaiah's later ministry

- 34–35: A vision of Zion, perhaps a later addition;

- 36–39: Stories of Isaiah's life, some from the Book of Kings

- Deutero-Isaiah/Second Isaiah (chapters 40–54), with two major divisions, 40–48 and 49–54, the first emphasising Israel, the second Zion and Jerusalem:[22]

- An introduction and conclusion stressing the power of God's word over everything;

- A second introduction and conclusion within these in which a herald announces salvation to Jerusalem;

- Fragments of hymns dividing various sections;

- The role of foreign nations, the fall of Babylon, and the rise of Cyrus as God's chosen one;

- Four "Servant Songs" personalising the message of the prophet;

- Several longer poems on topics such as God's power and invitations to Israel to trust in him;

- Trito-Isaiah/Third Isaiah (chapters 55–66):

- A collection of oracles by unknown prophets in the years immediately after the return from Babylon.[23]

Composition[edit]

Authorship[edit]

While it is widely accepted that the book of Isaiah is rooted in a historic prophet called Isaiah, who lived in the Kingdom of Judah during the 8th century BCE, it is also widely accepted that this prophet did not write the entire book of Isaiah.[8][24] The observations which have led to this are as follows:

- Historical situation: Chapters 40–55 presuppose that Jerusalem has already been destroyed (they are not framed as prophecy) and the Babylonian exile is already in effect – they speak from a present in which the Exile is about to end. Chapters 56–66 assume an even later situation, in which the people are already returned to Jerusalem and the rebuilding of the Temple is already under way.[25]

- Anonymity: Isaiah's name suddenly stops being used after chapter 39.[26]

- Style: There is a sudden change in style and theology after chapter 40; numerous key words and phrases found in one section are not found in the other.[27]

The composition history of Isaiah reflects a major difference in the way authorship was regarded in ancient Israel and in modern societies; the ancients did not regard it as inappropriate to supplement an existing work while remaining anonymous.[28] While the authors are anonymous, it is plausible that all of them were priests, and the book may thus reflect Priestly concerns, in opposition to the increasingly successful reform movement of the Deuteronomists.[29]

Historical context[edit]

The historic Isaiah ben Amoz lived in the Kingdom of Judah during the reigns of four kings from the mid to late 8th-century BCE.[24][30] During this period, Assyria was expanding westward from its origins in modern-day northern Iraq towards the Mediterranean, destroying first Aram (modern Syria) in 734–732 BCE, then the Kingdom of Israel in 722–721, and finally subjugating Judah in 701.[31] Proto-Isaiah is divided between verse and prose passages, and a currently popular theory is that the verse passages represent the prophecies of the original 8th-century Isaiah, while the prose sections are "sermons" on his texts composed at the court of Josiah a hundred years later, at the end of the 7th century.[32]

The conquest of Jerusalem by Babylon and the exile of its elite in 586 BCE ushered in the next stage in the formation of the book. Deutero-Isaiah addresses himself to the Jews in exile, offering them the hope of return.[33] This was the period of the meteoric rise of Persia under its king Cyrus the Great – in 559 BCE he succeeded his father as ruler of a small vassal kingdom in modern eastern Iran, by 540 he ruled an empire stretching from the Mediterranean to Central Asia, and in 539 he conquered Babylon.[34] Deutero-Isaiah's predictions of the imminent fall of Babylon and his glorification of Cyrus as the deliverer of Israel date his prophecies to 550–539 BCE, and probably towards the end of this period.[35]

The Persians ended the Jewish exile, and by 515 BCE the exiles, or at least some of them, had returned to Jerusalem and rebuilt the Temple. The return, however, was not without problems: the returnees found themselves in conflict with those who had remained in the country and who now owned the land, and there were further conflicts over the form of government that should be set up. This background forms the context of Trito-Isaiah.[33]

Themes[edit]

Overview[edit]

Isaiah is focused on the main role of Jerusalem in God's plan for the world, seeing centuries of history as though they were all the single vision of the 8th-century prophet Isaiah.[17] Proto-Isaiah speaks of Israel's desertion of God and what will follow: Israel will be destroyed by foreign enemies, but after the people, the country and Jerusalem are punished and purified, a holy remnant will live in God's place in Zion, governed by God's chosen king (the messiah), under the presence and protection of God; Deutero-Isaiah has as its subject the liberation of Israel from captivity in Babylon in another Exodus, which the God of Israel will arrange using Cyrus, the Persian conqueror, as his agent; Trito-Isaiah concerns Jerusalem, the Temple, the Sabbath, and Israel's salvation.[36] (More explicitly, it concerns questions current among Jews living in Jerusalem and Palestine in the post-Exilic period about who is a God-loving Jew and who is not).[37] Walter Brueggemann has described this overarching narrative as "a continued meditation upon the destiny of Jerusalem".[38]

Holiness, righteousness, and God's plan[edit]

God's plan for the world is based on his choice of Jerusalem as the place where he will manifest himself, and of the line of David as his earthly representative – a theme that may possibly have been created through Jerusalem's reprieve from Assyrian attack in 701 BCE. [39] God is "the holy one of Israel"; justice and righteousness are the qualities that mark the essence of God, and Israel has offended God through unrighteousness.[10] Isaiah speaks out for the poor and the oppressed and against corrupt princes and judges, but unlike the prophets Amos and Micah he roots righteousness not in Israel's covenant with God but in God's holiness.[10]

Monotheism[edit]

Isaiah 44:6 contains the first clear statement of monotheism: "I am the first and I am the last; beside me there is no God". In Isaiah 44:09–20, this is developed into a satire on the making and worship of idols, mocking the foolishness of the carpenter who worships the idol that he himself has carved. While Yahweh had shown his superiority to other gods before, in Second Isaiah, he becomes the sole God of the world. This model of monotheism became the defining characteristic of post-Exilic Judaism and became the basis for Christianity and Islam.[12]

A new Exodus[edit]

A central theme in Second Isaiah is that of a new Exodus – the return of the exiled people Israel from Babylon to Jerusalem. The author imagines a ritualistic return to Zion (Judah) led by Yahweh. The importance of this theme is indicated by its placement at the beginning and end of Second Isaiah (40:3–5, 55:12–13). This new Exodus is repeatedly linked with Israel's Exodus from Egypt to Canaan under divine guidance, but with new elements. These links include the following:

- The original Exodus participants left "in great haste" (Ex 12:11, Deut 16:3), whereas the participants in this new Exodus will "not go out in great haste" (Isa 52:12).

- The land between Egypt and Canaan of the first Exodus was a "great and terrible wilderness, an arid wasteland" (Deut 8:15), but in this new Exodus, the land between Babylon (Mesopotamia) and the Promised Land will be transformed into a paradise, where the mountains will be lowered and the valleys raised to create level road (Isa 40:4).

- In the first Exodus, water was provided by God, but scarcely. In the new Exodus, God will "make the wilderness a pool of water, and the dry land springs of water" (Isa 41:18).[40]

Later interpretation and influence[edit]

2nd Temple Judaism (515 BCE – 70 CE)[edit]

Isaiah was one of the most popular works in the period between the foundation of the Second Temple c. 515 BCE and its destruction by the Romans in 70 CE.[13] Isaiah's "shoot [which] will come up from the stump of Jesse" is alluded to or cited in the Psalms of Solomon and various apocalyptic works including the Similitudes of Enoch, 2 Baruch, 4 Ezra, and the third of the Sibylline oracles, all of which understood it to refer to a/the messiah and the messianic age.[41] Isaiah 6, in which Isaiah describes his vision of God enthroned in the Temple, influenced the visions of God in works such as the "Book of the Watchers" section of the Book of Enoch, the Book of Daniel and others, often combined with the similar vision from the Book of Ezekiel.[42] A very influential portion of Isaiah was the four so-called Songs of the Suffering Servant from Isaiah 42, 49, 50 and 52, in which God calls upon his servant to lead the nations (the servant is horribly abused, sacrifices himself in accepting the punishment due others, and is finally rewarded). Some Second Temple texts, including the Wisdom of Solomon and the Book of Daniel identified the Servant as a group – "the wise" who "will lead many to righteousness" (Daniel 12:3) – but others, notably the Similitudes of Enoch, understood it in messianic terms.[43] The earliest Christians, building on this second tradition, interpreted Isaiah 52:13–53:12, the fourth of the songs, as a prophecy of the death and exaltation of Jesus, a role which Jesus himself accepted according to Luke 4:17–21.[44]

Christianity[edit]

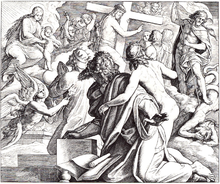

The Book of Isaiah has been immensely influential in the formation of Christianity, from the devotion to the Virgin Mary to anti-Jewish polemic, medieval passion iconography, and modern Christian feminism and liberation theology. The regard in which Isaiah was held was so high that the book was frequently called "the Fifth Gospel", the prophet who spoke more clearly of Christ and the Church than any others.[14] Its influence extends beyond the Church and Christianity to English literature and to Western culture in general, from the libretto of Handel's Messiah to a host of such everyday phrases as "swords into ploughshares" and "voice in the wilderness".[15]

The Gospel of John quotes Isaiah 6:10 and states that "Isaiah said this because he saw Jesus’ glory and spoke about him."[45] Isaiah makes up 27 of the 37 quotations from the prophets in the Pauline epistles, and takes pride of place in the Gospels and in Acts of the Apostles.[46] Isaiah 7:14, where the prophet is assuring king Ahaz that God will save Judah from the invading armies of Israel and Syria, forms the basis for Matthew 1:23's doctrine of the virgin birth,[47] while Isaiah 40:3–5's image of the exiled Israel led by God and proceeding home to Jerusalem on a newly constructed road through the wilderness was taken up by all four Gospels and applied to John the Baptist and Jesus.[48]

Isaiah seems always to have had a prominent place in Jewish Bible use, and it is probable that Jesus himself was deeply influenced by Isaiah.[49] Thus many of the Isaiah passages that are familiar to Christians gained their popularity not directly from Isaiah but from the use of them by Jesus and the early Christian authors – this is especially true of the Book of Revelation, which depends heavily on Isaiah for its language and imagery.[50]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

Citations[edit]

- ^ Cate 1990b, p. 413.

- ^ Sweeney 1998, p. 75-76.

- ^ Clifford 1992, p. 473.

- ^ a b c Petersen 2002, pp. 47–48.

- ^ Sweeney 1998, p. 76-77.

- ^ Lemche 2008, p. 96.

- ^ Sweeney 1998, pp. 78–79.

- ^ a b Brueggemann 2003, p. 159.

- ^ a b Sweeney 1998, pp. 79–80.

- ^ a b c Petersen 2002, p. 89-90.

- ^ Gnuse 1997, p. 87.

- ^ a b Coogan 2009, p. 335-336.

- ^ a b Hannah 2005, p. 7.

- ^ a b Sawyer 1996, p. 1-2.

- ^ a b Sawyer 1996, pp. 1–2.

- ^ Goldingay 2001, pp. 22–23.

- ^ a b Sweeney 1998, p. 78.

- ^ Soggin 1989, p. 394.

- ^ Petersen 2002, p. 47-48.

- ^ Sweeney 1998, p. 78-79.

- ^ Boadt 1984, p. 325.

- ^ Boadt 1984, pp. 418–19.

- ^ Boadt 1984, p. 444.

- ^ a b Stromberg 2011, p. 2.

- ^ Stromberg 2011, p. 2-4.

- ^ Childs 2001, p. 3.

- ^ Cate 1990b, p. 414.

- ^ Stromberg 2011, p. 4.

- ^ Barker 2003, p. 494.

- ^ Brettler 2010, p. 161-162.

- ^ Sweeney 1998, p. 75.

- ^ Goldingay 2001, p. 4.

- ^ a b Barker 2003, p. 524.

- ^ Whybray 2004, p. 11.

- ^ Whybray 2004, p. 11-12.

- ^ Lemche 2008, p. 18-20.

- ^ Lemche 2008, p. 233.

- ^ Brueggemann 2003, p. 160.

- ^ Petersen 2002, p. 91-94.

- ^ Coogan 2009, p. 333.

- ^ Hannah 2005, p. 11.

- ^ Hannah 2005, pp. 22–23.

- ^ Hannah 2005, p. 27-31.

- ^ Barker 2003, pp. 534–35.

- ^ John 12:39-41

- ^ Sawyer 1996, p. 22.

- ^ Sweeney 1996, p. 161.

- ^ Brueggemann 2003, p. 174.

- ^ Sawyer 1996, p. 23.

- ^ Sawyer 1996, p. 25.

Works cited[edit]

- Bandstra, Barry L. (2008). Reading the Old Testament: an introduction to the Hebrew Bible. Cengage Learning. ISBN 0495391050.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Barker, Margaret (2003). "Isaiah". In Dunn, James D. G.; Rogerson, John William (eds.). Eerdmans Commentary on the Bible. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802837110.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Blenkinsopp, Joseph (2002). Isaiah 40–55: A new translation with introduction and commentary. Doubleday. ISBN 0-385-49717-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Blenkinsopp, Joseph (2003). Isaiah 56–66: A new translation with introduction and commentary. Doubleday. ISBN 0-385-50174-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Boadt, Lawrence (1984). Reading the Old Testament:An Introduction. Paulist Press. ISBN 9780809126316.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Brettler, Marc Zvi (2010). How to read the Bible. Jewish Publication Society. ISBN 978-0-8276-0775-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Brueggemann, Walter (2003). An introduction to the Old Testament: the canon and Christian imagination. Westminster John Knox. ISBN 978-0-664-22412-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cate, Robert L. (1990a). "Isaiah". In Mills, Watson E.; Bullard, Roger Aubrey (eds.). Mercer Dictionary of the Bible. Mercer University Press. ISBN 9780865543737.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cate, Robert L. (1990b). "Isaiah, book of". In Mills, Watson E.; Bullard, Roger Aubrey (eds.). Mercer Dictionary of the Bible. Mercer University Press. ISBN 9780865543737.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Childs, Brevard S. (2001). Isaiah. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 9780664221430.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Clifford, Richard (1992). "Isaiah, Book of: Second Isaiah". In Freedman, David Noel (ed.). The Anchor Bible Dictionary. 3. Doubleday. p. 473. ISBN 0385193610.

- Cohn-Sherbok, Dan (1996). The Hebrew Bible. Cassell. ISBN 0-304-33702-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Coogan, Michael D. (2009). A Brief Introduction to the Old Testament. Oxford University Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gnuse, Robert Karl (1997). No Other Gods: Emergent Monotheism in Israel. Continuum. ISBN 9781850756576.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Goldingay, John (2001). Isaiah. Hendrickson Publishers. ISBN 0-85364-734-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Goldingay, John (2005). The message of Isaiah 40–55: a literary-theological commentary. Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN 9780567030382.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hannah, Darrell D. (2005). "Isaiah Within Judaism of the Second Temple Period". In Moyise, Steve; Menken, Maarten J.J. (eds.). Isaiah in the New Testament: The New Testament and the Scriptures of Israel. Continuum. ISBN 9780802837110.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lemche, Niels Peter (2008). The Old Testament between theology and history: a critical survey. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 9780664232450.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Petersen, David L. (2002). The Prophetic Literature: An Introduction. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 9780664254537.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sawyer, John F.A. (1996). The Fifth Gospel: Isaiah in the History of Christianity. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521565967.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Soggin, J. Alberto (1989). Introduction to the Old Testament: From Its Origins to the Closing of the Alexandrian Canon. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 0-664-21331-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Stromberg, Jake (2011). An Introduction to the Study of Isaiah. Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN 9780567363305.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sweeney, Marvin A. (1996). Isaiah 1–39: With an Introduction to Prophetic Literature. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802841001.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sweeney, Marvin A. (1998). "The Latter Prophets". In McKenzie, Steven L.; Graham, Matt Patrick (eds.). The Hebrew Bible Today: An Introduction to Critical Issues. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 9780664256524.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Whybray, R. N. (2004). The Second Isaiah. T&T Clarke. ISBN 9780567084248.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links[edit]

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Book of Isaiah |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Book of Isaiah. |

Translations[edit]

- Book of Isaiah - Hebrew, side by side with English

- Book of Isaiah (English translation [with Rashi's commentary] at Chabad.org)

- Bible Gateway

Isaiah public domain audiobook at LibriVox

Isaiah public domain audiobook at LibriVox

Book of Isaiah

| ||

| Preceded by Kings |

Hebrew Bible | Succeeded by Jeremiah |

| Preceded by Song of Songs |

Protestant Old Testament | |

| Preceded by Sirach |

Roman Catholic & Eastern Old Testament | |