Cratylus (dialogue)

| Part of a series on |

| Platonism |

|---|

|

| The dialogues of Plato |

|

| Allegories and metaphors |

| Related articles |

| Related categories |

|

► Plato |

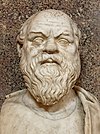

Cratylus (/krəˈtaɪləs/; Ancient Greek: Κρατύλος, Kratylos) is the name of a dialogue by Plato. Most modern scholars agree that it was written mostly during Plato's so-called middle period.[1] In the dialogue, Socrates is asked by two men, Cratylus and Hermogenes, to tell them whether names are "conventional" or "natural", that is, whether language is a system of arbitrary signs or whether words have an intrinsic relation to the things they signify.

The individual Cratylus was the first intellectual influence on Plato (Sedley).[2] Aristotle states that Cratylus influenced Plato by introducing to him the teachings of Heraclitus, according to MW. Riley.[3]

Summary[edit]

The subject of Cratylus is the correctness of names (περὶ ὀνομάτων ὀρθότητος),[4] in other words, it is a critique on the subject of naming (Baxter).[5]

When discussing an ὄνομα[6] (onoma [7][8][9]) and how it would relate to its subject, Socrates compares the original creation of a word to the work of an artist.[10] An artist uses color to express the essence of his subject in a painting. In much the same way, the creator of words uses letters containing certain sounds to express the essence of a word's subject. There is a letter that is best for soft things, one for liquid things, and so on.[11] He comments:

the best possible way to speak consists in using names all (or most) of which are like the things they name (that is, are appropriate to them), while the worst is to use the opposite kind of names.[12]

One countering position, held by Hermogenes, is that names have come about due to custom and convention. They do not express the essence of their subject, so they can be swapped with something unrelated by the individuals or communities who use them.[13]

The line between the two perspectives is often blurred.[clarification needed] During more than half of the dialogue, Socrates makes guesses at Hermogenes' request as to where names and words have come from. These include the names of the Olympian gods, personified deities, and many words that describe abstract concepts. He examines whether, for example, giving names of "streams" to Cronus and Rhea (Ροή – flow or space) are purely accidental.

Don't you think he who gave to the ancestors of the other gods the names “Rhea” and “Cronus” had the same thought as Heracleitus? Do you think he gave both of them the names of streams (ῥευμάτων ὀνόματα) merely by chance?[14]

The Greek term "ῥεῦμα" may refer to the flow of any medium and is not restricted to the flow of water or liquids.[15] Many of the words which Socrates uses as examples may have come from an idea originally linked to the name, but have changed over time. Those of which he cannot find a link, he often assumes have come from foreign origins or have changed so much as to lose all resemblance to the original word. He states, "names have been so twisted in all manner of ways, that I should not be surprised if the old language when compared with that now in use would appear to us to be a barbarous tongue."[16]

The final theory of relations between name and object named is posited by Cratylus, a disciple of Heraclitus, who believes that names arrive from divine origins, making them necessarily correct. Socrates rebukes this theory by reminding Cratylus of the imperfection of certain names in capturing the objects they seek to signify. From this point, Socrates ultimately rejects the study of language, believing it to be philosophically inferior to a study of things themselves.

Hades' name in Cratylus[edit]

An extensive section of Plato's dialogue Cratylus is devoted to the etymology of the god Hades' name, in which Socrates is arguing for a folk etymology not from "unseen" but from "his knowledge (eidenai) of all noble things". The origin of Hades' name is uncertain, but has generally been seen as meaning "The Unseen One" since antiquity. Modern linguists have proposed the Proto-Greek form *Awides ("unseen").[17] The earliest attested form is Aḯdēs (Ἀΐδης), which lacks the proposed digamma. West argues instead for an original meaning of "the one who presides over meeting up" from the universality of death.[18]

Hades' Name in Classical Greek[edit]

The /w/ sound was lost at various times in various dialects, mostly before the classical period.

In Ionic, /w/ had probably disappeared before Homer's epics were written down (7th century BC), but its former presence can be detected in many cases because its omission left the meter defective. For example, the words ἄναξ (/ánaks/; 'tribal king', 'lord', '(military) leader')[19] and οἶνος (/óînos/; 'wine') are sometimes found in the Iliad in the meter where a word starting with a consonant would be expected. Cognate-analysis and earlier written evidence shows that earlier these words would have been ϝάναξ (/wánaks/, attested to in this form in Mycenaean Greek) and ϝοῖνος (/wóînos/; cf. Cretan Doric ibêna, cf. Latin vīnum and English "wine").[20][21]

Appropriate sounds[edit]

- ρ ('r') is a "tool for copying every sort of motion (κίνησις)."[22][foot 1]

- ι ('i') for imitating "all the small things that can most easily penetrate everything",[23][foot 2]

- φ ('phi'), ψ ('psi'). σ ('s'), and ζ ('z') as "all these letters are pronounced with an expulsion of breath", they are most appropriate for imitating "blowing or hard breathing".[24][foot 3]

- δ ('d') and τ ('t') as both involve "compression and [the] stopping of the power of the tongue" when pronounced, they are most appropriate for words indicating a lack or stopping of motion.[24][25][foot 4]

- λ ('l'), as "the tongue glides most of all" when pronounced, it is most appropriate for words denoting a sort of gliding.[25][foot 5]

- γ ('g') best used when imitating "something cloying", as the gliding of the tongue is stopped when pronounced.[25][foot 6]

- ν ('n') best used when imitating inward things, as it is "sounded inwardly".[25][26][foot 7]

- α ('a'), η ('long e') best used when imitating large things, as they are both "pronounced long".[26][foot 8]

- ο ('o') best used when imitating roundness.[26][foot 9]

Although these are clear examples of onomatopoeia, Socrates's statement that words are not musical imitations of nature suggests that Plato didn't believe that language itself generates from sound words.[27]

Platonic theory of forms[edit]

Plato's theory of forms also makes an appearance. For example, no matter what a hammer is made out of, it is still called a "hammer", and thus is the form of a hammer:

Socrates: So mustn't a rule-setter also know how to embody in sounds and syllables the name naturally suited to each thing? And if he is to be an authentic giver of names, mustn't he, in making and giving each name, look to what a name itself is? And if different rule-setters do not make each name out of the same syllables, we mustn't forget that different blacksmiths, who are making the same tool for the same type of work, don't all make it out of the same iron. But as long as they give it the same form--even if that form is embodied in different iron--the tool will be correct, whether it is made in Greece or abroad. Isn't that so?[28]

Plato's theory of forms again appears at 439c, when Cratylus concedes the existence of "a beautiful itself, and a good itself, and the same for each one of the things that are".[29]

Texts and translations[edit]

An early translation was made by Thomas Taylor in 1804.

Plato: Cratylus, Parmenides, Greater Hippias, Lesser Hippias. With translation by Harold N. Fowler. Loeb Classical Library 167. Harvard Univ. Press (originally published 1926). ISBN 9780674991859 HUP listing

Plato: Opera, volume I. Oxford Classical Texts. ISBN 978-0198145691

Plato: Complete Works. Hackett, 1997. ISBN 978-0872203495

See also[edit]

Footnotes[edit]

- ^ e.g. rhein ('flowing'), rhoe ('flow'), tromos ('trembling'), trechein ('running'), krouein ('striking'), thrauein ('crushing'), ereikein ('rending'), thruptein ('breaking'), kermatizein ('crumbling'), rhumbein ('whirling').

- ^ e.g. ienai ('moving'), hiesthai ('hastening').

- ^ e.g. psuchron ('chilling'), zeon ('seething'), seiesthai ('shaking'), seismos ('quaking').

- ^ e.g. desmos ('shackling'), stasis ('rest').

- ^ e.g. olisthanein ('glide'), leion ('smooth'), liparon ('sleek'), kollodes ('viscous').

- ^ e.g. glischron ('gluey'), gluku ('sweet'), gloiodes ('clammy').

- ^ e.g. endon ('within'), entos ('inside').

- ^ e.g. mega ('large'), mekos ('length').

- ^ e.g. gongulon ('round').

References[edit]

- ^ pp. 6, 13-14, David Sedley, Plato's Cratylus, Cambridge U Press 2003.

- ^ D Sedley (Laurence Professor of Ancient Philosophy in the University of Cambridge) - Plato's Cratylus (p.2) Cambridge University Press, 6 Nov 2003 ISBN 1139439197 [Retrieved 2015-3-26]

- ^ MW. Riley (Professor of Classics and Tutor, formerly Director, of the Integral Liberal Arts Program at Saint Mary's College in Moraga, California c.2005) - Plato's Cratylus: Argument, Form, and Structure (p.29) Publication:Rodopi, 1 Jan 2005 [Retrieved 2015-3-27]

- ^ F Ademollo (studied classics at the University of Florence and has held postdoctoral research positions at the University of Florence and at the Scuola Normale Superiore) - The Cratylus of Plato: A Commentary (p.I) Cambridge University Press, 3 Feb 2011 ISBN 1139494694 [Retrieved 2015-3-26]

- ^ T M. S. Baxter (holds a Ph.D. in Ancient Philosophy from the University of Cambridge) - The Cratylus: Plato's Critique of Naming Volume 58 of Philosophia Antiqua : A Series of Studies on Ancient Philosophy BRILL, 1992 ISBN 9004095977 [Retrieved 2015-3-26]

- ^ Perseus - Latin Word Study Tool - onoma Tufts University [Retrieved 2015-3-20]

- ^ AC Yu - Early China/Ancient Greece: Thinking through Comparisons (edited by S Shankman, SW Durrant) SUNY Press, 1 Feb 2012 ISBN 0791488942 [Retrieved 2015-3-20]

- ^ Cratylus - Translated by Benjamin Jowett [Retrieved 2015-3-20]

- ^ Strong's Concordance - onoma Bible Hub (ed. used as secondary verification of onoma)

- ^ Cratylus 390d-e.

- ^ Cratylus 431d.

- ^ Cratylus 435c.

- ^ Cratylus 383a-b.

- ^ Cratylus 402b

- ^ Entry ῥεῦμα at LSJ. Besides the flow liquids, "ῥεῦμα" may refer to the flow of sound (Epicurus,Ep. 1p.13U), to the flow of fortune etc.

- ^ Cratylus 421d

- ^ According to Dixon-Kennedy, https://archive.org/stream/MikeDixonKennedy.......encyclopediaOfGrecoRomanMythologybyHouseOfBooks/MikeDixonKennedy.......encyclopediaOfGreco-romanMythologybyHouseOfBooks#page/n159/mode/2up p. 143] (following Kerényi 1951, p. 230) says "...his name means 'the unseen', a direct contrast to his brother Zeus, who was originally seen to represent the brightness of day". Ivanov, p. 284, citing Beekes 1998, pp. 17–19, notes that derivation of Hades from a proposed *som wid- is semantically untenable; see also Beekes 2009, p. 34.

- ^ West, p. 394.

- ^ ἄναξ. Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert; A Greek–English Lexicon at the Perseus Project.

- ^ Chadwick, John (1958). The Decipherment of Linear B. Second edition (1990). Cambridge UP. ISBN 0-521-39830-4.

- ^ οἶνος. Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert; A Greek–English Lexicon at the Perseus Project:

- ^ Cratylus 426c-e.

- ^ Cratylus 426e-427a.

- ^ a b Cratylus 427a.

- ^ a b c d Cratylus 427b.

- ^ a b c Cratylus 427c.

- ^ Claramonte, Manuel Breva (1983). Sanctius Theory of Language: A Contribution to the History of Renaissance Linguistic. John Benjamins Publishing, p. 24. ISBN 9027245053

- ^ Cratylus 389d-390a1.

- ^ Cratylus 439c-d.

External links[edit]

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Greek Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- Bibliography on Plato's Cratylus (PDF)

- Cratylus translation by Benjamin Jowett (1892) starting at Page 323

Cratylus public domain audiobook at LibriVox

Cratylus public domain audiobook at LibriVox