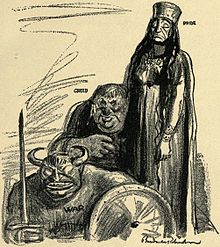

Greed

Greed (or avarice) is an uncontrolled longing for increase in the acquisition or use: of material gain (be it food, money, land, or animate/inanimate possessions); or social value, such as status, or power. Greed has been identified as an undesirable behavior throughout known human history.

Nature of Greed[edit]

As a secular psychological concept, greed is an inordinate desire to acquire or possess more than one needs. The degree of inordinance is related to the inability to control the reformulation of "wants" once desired "needs" are eliminated. Erich Fromm described greed as "a bottomless pit which exhausts the person in an endless effort to satisfy the need without ever reaching satisfaction." It is typically used to criticize those who seek excessive material wealth, although it may equally be applied to the need to feel more excessively moral, social, or otherwise better than someone else.

The purpose for greed, and any actions associated with it, may be to promote personal or family survival. It may also be an intent to deny or obstruct competitors from potential means (for basic survival and comfort) or future opportunities; therefore being insidious or tyrannical and having a negative connotation. Alternately, the purpose could be defense or counteraction from such dangers being threatened by others.

One consequence of greedy activity may be an inability to sustain any of the costs or burdens associated with that which has been or is being accumulated, leading to a backfire or destruction, whether of self or more generally. Other outcomes may include a degradation of social position, or exclusion from community protections. So, the level of "inordinance" of greed pertains to the amount of vanity, malice or burden associated with it.

Views[edit]

Any animal examples of greed in historic observations are often an attribution of human motication to domesticated species. The dog-in-the-manger, or piggish behaviors are typical examples. However the wolverine, whose scientific name (Gulo gulo)) means "glutton", is known both for its outsized appetite, and for spoiling any food remaining after it has gorged[1]

Ancient concepts of greed come to us from nearly every culture. In Classical Greek thought; pleonexy (the unjust desire for tangible/intangible worth attaining to others) is discussed in the works of Plato and Aristotle, among others.[2] A pan-Hellenic disapproval of greed is indicated by the mythic punishment meted to Tantalus, from whom ever-present food and water was eternally withheld. Contemporary writers and politicians fix blame for the end of the Roman Republic in a large part on greed, from Sallust and Plutarch[3] to the Gracchi and Cicero. The three-headed Zoroastrian demon Aži Dahāka became a fixed part of the folklore of the Persian empires, representing unslaked desire. In the Sanskrit Dharmashastras the "root of all immorality is lobha (greed)."[4], as stated in the Laws of Manu (7:49).[5] In early China, both the Shai jan jing and the Zuo zhuan texts count the greedy Taotie among the malevolent Four Perils besetting gods and men. In early allegoric literature of many lands, greed may also be represented by the fox.

Greed was often applied as a racial pejorative by the ancient Greeks and Romans against Egyptians, Punics, or other Oriental peoples[6], as well as enemies or people whose customs were considered strange. By the Middle Ages the insult was widely directed towards Jews.[7]

In the Books of Moses, the commandments of the sole deity are written in the book of Exodus (20:2-17), and again in Deuteronomy (5:6-21); two of these particularly deal directly with greed, prohibiting theft and covetousness. These commandments are moral foundations of not only Judaism, but also of Christianity, Islam, Unitarian Universalism, and the Baháʼí Faith among others. In the Quran we are advised do not spend wastefully, indeed, the wasteful are brothers of the devils..., but also do not make your hand [as though] chained to your neck..."[8] The Christian Gospels quote Jesus as saying, "“Watch out! Be on your guard against all kinds of greed; a man's life does not consist in the abundance of his possessions”[9], and "For everything in the world—the lust of the flesh, the lust of the eyes, and the pride of life—comes not from the Father but from the world.".[10]

In the fifth centiry, St. Augustine wrote: “Greed is not a defect in the gold that is desired but in the man who loves it perversely by falling from justice which he ought to esteem as incomparably superior to gold..."[11] St. Thomas Aquinas states greed "is a sin against God, just as all mortal sins, in as much as man condemns things eternal for the sake of temporal things."[12]:A1 He also wrote that "greed can be “a sin directly against one’s neighbor, since one man cannot over-abound (superabundare) in external riches, without another man lacking them, for temporal goods cannot be possessed by many at the same time."

Dante's 14th century epic poem Inferno assigns those committed to the deadly sin of greed to punishment in the fourth of the nine circles of Hell. The inhabitants are misers, hoarders, and spendthrifts; they must constantly battle one another. The guiding spirit, Virgil, tells the poet these souls have lost their personality in their disorder, and are no longer recognizable: "That ignoble life, Which made them vile before, now makes them dark, And to all knowledge indiscernible."[13] In Dante's Purgatory, avaricious penitents were bound and laid face down on the ground for having concentrated too much on earthly thoughts. Dante's near-contemporary, Geoffrey Chaucer, wrote of greed in his Prologue to The Pardoner's Tale these words: "Radix malorum est Cupiditas"(or “the root of all evil is greed”)[14]; however the Pardoner himself serves us as a charicature of churchly greed.[15]

Thomas Hobbes argues in his Leviathan that greed is a integral part of the natural condition of man. John Locke, however, claimed unused property is wasteful and an offence against nature, because "as anyone can make use of to any advantage of life before it spoils; so much he may by his labour fix a property in. Whatever is beyond this, is more than his share, and belongs to others.”[16]

Meher Baba dictated that "Greed is a state of restlessness of the heart, and it consists mainly of craving for power and possessions. Possessions and power are sought for the fulfillment of desires. Man is only partially satisfied in his attempt to have the fulfillment of his desires, and this partial satisfaction fans and increases the flame of craving instead of extinguishing it. Thus greed always finds an endless field of conquest and leaves the man endlessly dissatisfied. The chief expressions of greed are related to the emotional part of man."[17]

Ivan Boesky famously defended greed in an 18 May 1986 commencement address at the UC Berkeley's School of Business Administration, in which he said, "Greed is all right, by the way. I want you to know that. I think greed is healthy. You can be greedy and still feel good about yourself".[18] This speech inspired the 1987 film Wall Street, which features the famous line spoken by Gordon Gekko: "Greed, for lack of a better word, is good. Greed is right, greed works. Greed clarifies, cuts through, and captures the essence of the evolutionary spirit. Greed, in all of its forms; greed for life, for money, for love, knowledge has marked the upward surge of mankind."[19]

Inspirations[edit]

Scavenging and hoarding of materials or objects, theft and robbery, especially by means of violence, trickery, or manipulation of authority are all actions that may be inspired by greed. Such misdeeds can include simony, where one profits from soliciting goods within the actual confines of a church. A well-known example of greed is the pirate Hendrick Lucifer, who fought for hours to acquire Cuban gold, becoming mortally wounded in the process. He died of his wounds hours after having transferred the booty to his ship.[20]

Genetics[edit]

Some research suggests there is a genetic basis for greed. It is possible people who have a shorter version of the ruthlessness gene (AVPR1a) may behave more selfishly.[21]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ https://www.visionlearning.com/blog/2014/12/17/wolverines-give-insight-evolution-greed/

- ^ https://countercurrents.org/2018/10/the-evolution-of-greed-from-aristotle-to-gordon-gekko

- ^ http://www.reallycoolblog.com/greed-power-and-prestige-explaining-the-fall-of-the-roman-republic/

- ^ https://qz.com/india/1041986/wealth-interest-and-greed-the-dharma-of-doing-business-in-medieval-india/

- ^ https://www.sacred-texts.com/hin/manu/manu07.htm

- ^ The Invention of Racism in Classical Antiquity, Benjamin Isaac, Princeton University Press, 2004; ISBN 0691-11691-1

- ^ https://www.myjewishlearning.com/article/usury-and-moneylending-in-judaism/

- ^ https://quran.com/17/26-36?translations=20

- ^ Luke 12:15

- ^ John 2:16

- ^ https://www.goodreads.com/quotes/870546-greed-is-not-a-defect-in-the-gold-that-is,

- ^ Thomas Aquinas. "The Summa Theologica II-II.Q118 (The vices opposed to liberality, and in the first place, of covetousness)" (1920, Second and Revised ed.). New Advent.

- ^ https://www.owleyes.org/text/dantes-inferno/read/canto-7#root-422366-1

- ^ https://sites.fas.harvard.edu/~chaucer/teachslf/pard-par.htm, line 426

- ^ https://partiallyexaminedlife.com/2018/11/23/a-philosophical-horror-story-chaucers-the-pardoners-tale/

- ^ https://www.earlymoderntexts.com/assets/pdfs/locke1689a.pdf, Chapter 5

- ^ Baba, Meher (1967). Discourses. Volume II. San Francisco: Sufism Reoriented. p. 27.

- ^ Gabriel, Satya J (November 21, 2001). "Oliver Stone's Wall Street and the Market for Corporate Control". Economics in Popular Film. Mount Holyoke. Retrieved 2008-12-10.

- ^ Ross, Brian (November 11, 2005). "Greed on Wall Street". ABC News. Retrieved 2008-03-18.

- ^ Dreamtheimpossible (September 14, 2011). "Examples of greed". Archived from the original on January 18, 2012. Retrieved October 4, 2011.

- ^ 'Ruthlessness gene' discovered