Himinbjörg

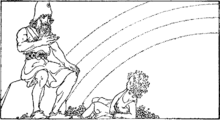

In Norse mythology, Himinbjörg (Old Norse "heaven's castle"[1] or "heaven mountain"[2]) is the home of the god Heimdallr. Himinbjörg is attested in the Poetic Edda, compiled from earlier traditional sources, and the Prose Edda and Heimskringla, both written in the 13th century by Snorri Sturluson. Himinbjörg is associated with Heimdallr in all sources. According to the Poetic Edda, Heimdallr dwells there as watchman for the gods and there drinks fine mead, whereas in the Prose Edda Himinbjörg is detailed as located where the burning rainbow bridge Bifröst meets heaven. Scholars have commented on the differences between the two attestations and linked the name of the mythical location to various place names.

Attestations[edit]

Himinbjörg receives a single mention in the Poetic Edda. In the poem Grímnismál, Odin (disguised as Grímnir), tortured, starved and thirsty, tells the young Agnar of a number of mythological locations. The eighth location he mentions is Himinbjörg, where he says Heimdallr drinks fine mead:

Benjamin Thorpe translation:

- Himinbiörg is the eighth, where Heimdall,

- it is said, rules o'er the holy fanes:

- there the gods' watchman, in his tranquil home,

- drinks joyful the good mead.[3]

Henry Adams Bellows translation:

- Himingbjorg is the eight, and Heimdall there

- O'er men hold sway, it is said;

- In his well-built house does the warder of heaven

- The good mead gladly drink.[4]

Regarding the above stanza, Henry Adams Bellows comments that "in stanza the two functions of Heimdall—as father of mankind [ . . . ] and as warder of the gods—seem both to be mentioned, but the second line in the manuscripts is apparently in bad shape, and in the editions it is more or less conjecture".[4]

In the Prose Edda, Himinbjörg is mentioned twice, both times in the book Gylfaginning. The first mention is found in chapter 27, where the enthroned figure of High informs Gangleri that Himinbjörg stands where the burning bridge Bifröst meets heaven.[5] Later, in chapter 27, High says that Heimdallr lives in Himinbjörg by Bifröst and there guards the bridge from mountain jotnar while sitting at the edge of heaven. The above-mentioned Grímnismál stanza is quoted shortly thereafter.[6]

In Ynglinga saga, compiled in Heimskringla, Snorri presents a euhemerized origin of the Norse gods and rulers descending from them. In chapter 5, Snorri asserts that the æsir settled in what is now Sweden and built various temples. Snorri writes that Odin settled in Lake Logrin "at a place which formerly was called Sigtúnir. There he erected a large temple and made sacrifices according to the custom of the Æsir. He took possession of the land as far as he had called it Sigtúnir. He gave dwelling places to the temple priests." Snorri adds that, after this, Njörðr dwelt in Nóatún, Freyr dwelt in Uppsala, Heimdallr at Himinbjörg, Thor at Þrúðvangr, Baldr at Breiðablik and that to everyone Odin gave fine estates.[7]

Theories[edit]

Regarding the differences between the Grímnismál and Gylfaginning attestations, scholar John Lindow says that while the bridge Bilröst "leads to the well, which is presumably at the center of the abode of the gods, Snorri's notion of Bilröst as the rainbow may have led him to put Himinbjörg at the end of heaven". Lindow further comments that the notion "is, however, consistent with the notion of Heimdall as a boundary figure".[2]

19th century scholar Jacob Grimm translates the name as "the heavenly hills", and links Himinbjörg to a few common nouns and place names in various parts of Germanic Europe. Grimm compares Himinbjörg to the Old Norse common noun himinfiöll for especially high mountains, and the Old High German Himilînberg ('heavenly mountains'), a place haunted by spirits in the Vita sancti Galli, a Himelberc in Liechtenstein and a Himilesberg near Fulda, Germany, besides more examples from Hesse, a Himmelsberg in Västergötland, Sweden and one, "alleged to be Heimdall's", in Halland, Sweden. Grimm further compares the Old Norse Himinvângar, cognate to Old Saxon hebanwang, hebeneswang, a term for "paradise" and the Old English Heofenfeld ('heavenly field') mentioned by Bede.[8]

Notes[edit]

References[edit]

- Bellows, Henry Adams (1923). The Poetic Edda. American-Scandinavian Foundation.

- Faulkes, Anthony (Trans.) (1995). Edda. Everyman. ISBN 0-460-87616-3

- Hollander, Lee M. (Trans.) (2007). Heimskringla: History of the Kings of Norway. University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-0-292-73061-8

- Grimm, Jacob (1882) translated by James Steven Stallybrass. Teutonic Mythology: Translated from the Fourth Edition with Notes and Appendix by James Stallybrass. Volume I. London: George Bell and Sons.

- Larrington, Carolyne (Trans.) (1999). The Poetic Edda. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-283946-2

- Lindow, John (2002). Norse Mythology: A Guide to the Gods, Heroes, Rituals, and Beliefs. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-515382-0

- Thorpe, Benjamin (Trans.) (1866) The Elder Edda of Saemund Sigfusson. Norrœna Society.

- Simek, Rudolf (2007) translated by Angela Hall. Dictionary of Northern Mythology. D.S. Brewer ISBN 0-85991-513-1