History of ancient Israel and Judah

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Israel |

|

| Ancient Israel and Judah |

| Second Temple period (530 BCE–70 CE) |

| Late Classic (70-636) |

| Middle Ages (636–1517) |

| Modern history (1517–1948) |

| State of Israel (1948–present) |

| History of the Land of Israel by topic |

| Related |

|

|

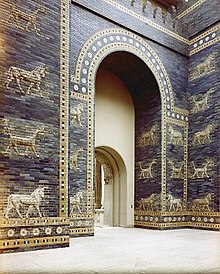

The Kingdom of Israel and the Kingdom of Judah were related kingdoms from the Iron Age period of the ancient Levant. The Kingdom of Israel emerged as an important local power by the 10th century BCE before falling to the Neo-Assyrian Empire in 722 BCE. Israel's southern neighbor, the Kingdom of Judah, emerged in the 9th or 8th century BCE and later became a client state of first the Neo-Assyrian Empire and then the Neo-Babylonian Empire before a revolt against the latter led to its destruction in 586 BCE. Following the fall of Babylon to the Achaemenid Empire under Cyrus the Great in 539 BCE, some Judean exiles returned to Jerusalem, inaugurating the formative period in the development of a distinctive Judahite identity in the province of Yehud Medinata.

During the Hellenistic classic period, Yehud was absorbed into the subsequent Hellenistic kingdoms that followed the conquests of Alexander the Great, but in the 2nd century BCE the Judaeans revolted against the Seleucid Empire and created the Hasmonean kingdom. This, the last nominally independent kingdom of Israel, gradually lost its independence from 63 BCE with its conquest by Pompey of Rome, becoming a Roman and later Parthian client kingdom. Following the installation of client kingdoms under the Herodian dynasty, the Province of Judea was wracked by civil disturbances, which culminated in the First Jewish–Roman War, the destruction of the Second Temple, the emergence of Rabbinic Judaism and Early Christianity. The name Judea (Iudaea) ceased to be used by Greco-Romans after the Bar Kochba revolt of 135 CE.

Periods[edit]

- Iron Age I: 1150[1] –950 BCE[2]

- Iron Age II: 950[3]–586 BCE

- Neo-Babylonian: 586–539 BCE

- Persian: 539–332 BCE

- Hellenistic: 333–53 BCE[4]

Other academic terms often used are:

- First Temple period (c. 1000–586 BCE)[5]

- Second Temple period (c. 516 BCE–70 CE)

Late Bronze Age background (1600–1150 BCE)[edit]

The eastern Mediterranean seaboard – the Levant – stretches 400 miles north to south from the Taurus Mountains to the Sinai Peninsula, and 70 to 100 miles east to west between the sea and the Arabian Desert.[6] The coastal plain of the southern Levant, broad in the south and narrowing to the north, is backed in its southernmost portion by a zone of foothills, the Shfela; like the plain this narrows as it goes northwards, ending in the promontory of Mount Carmel. East of the plain and the Shfela is a mountainous ridge, the "hill country of Judah" in the south, the "hill country of Ephraim" north of that, then Galilee and Mount Lebanon. To the east again lie the steep-sided valley occupied by the Jordan River, the Dead Sea, and the wadi of the Arabah, which continues down to the eastern arm of the Red Sea. Beyond the plateau is the Syrian desert, separating the Levant from Mesopotamia. To the southwest is Egypt, to the northeast Mesopotamia. The location and geographical characteristics of the narrow Levant made the area a battleground among the powerful entities that surrounded it.[7]

Canaan in the Late Bronze Age was a shadow of what it had been centuries earlier: many cities were abandoned, others shrank in size, and the total settled population was probably not much more than a hundred thousand.[8] Settlement was concentrated in cities along the coastal plain and along major communication routes; the central and northern hill country which would later become the biblical kingdom of Israel was only sparsely inhabited[9] although letters from the Egyptian archives indicate that Jerusalem was already a Canaanite city-state recognising Egyptian overlordship.[10] Politically and culturally it was dominated by Egypt,[11] each city under its own ruler, constantly at odds with its neighbours, and appealing to the Egyptians to adjudicate their differences.[9]

The Canaanite city state system broke down during the Late Bronze Age collapse,[12] and Canaanite culture was then gradually absorbed into that of the Philistines, Phoenicians and Israelites.[13] The process was gradual[14] and a strong Egyptian presence continued into the 12th century BCE, and, while some Canaanite cities were destroyed, others continued to exist in Iron Age I.[15]

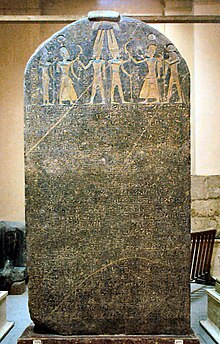

The name "Israel" first appears in the Merneptah Stele c. 1209 BCE: "Israel is laid waste and his seed is no more."[16] This "Israel" was a cultural and probably political entity, well enough established for the Egyptians to perceive it as a possible challenge, but an ethnic group rather than an organised state.[17]

Iron Age I (1150–950 BCE)[edit]

Archaeologist Paula McNutt says: "It is probably ... during Iron Age I [that] a population began to identify itself as 'Israelite'," differentiating itself from its neighbours via prohibitions on intermarriage, an emphasis on family history and genealogy, and religion.[18]

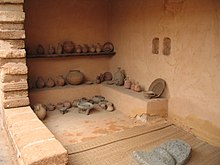

In the Late Bronze Age there were no more than about 25 villages in the highlands, but this increased to over 300 by the end of Iron Age I, while the settled population doubled from 20,000 to 40,000.[19] The villages were more numerous and larger in the north, and probably shared the highlands with pastoral nomads, who left no remains.[20] Archaeologists and historians attempting to trace the origins of these villagers have found it impossible to identify any distinctive features that could define them as specifically Israelite – collared-rim jars and four-room houses have been identified outside the highlands and thus cannot be used to distinguish Israelite sites,[21] and while the pottery of the highland villages is far more limited than that of lowland Canaanite sites, it develops typologically out of Canaanite pottery that came before.[22] Israel Finkelstein proposed that the oval or circular layout that distinguishes some of the earliest highland sites, and the notable absence of pig bones from hill sites, could be taken as markers of ethnicity, but others have cautioned that these can be a "common-sense" adaptation to highland life and not necessarily revelatory of origins.[23] Other Aramaean sites also demonstrate a contemporary absence of pig remains at that time, unlike earlier Canaanite and later Philistine excavations.

In The Bible Unearthed (2001), Finkelstein and Silberman summarised recent studies. They described how, up until 1967, the Israelite heartland in the highlands of western Palestine was virtually an archaeological terra incognita. Since then, intensive surveys have examined the traditional territories of the tribes of Judah, Benjamin, Ephraim, and Manasseh. These surveys have revealed the sudden emergence of a new culture contrasting with the Philistine and Canaanite societies existing in the Land of Israel earlier during Iron Age I.[24] This new culture is characterised by a lack of pork remains (whereas pork formed 20% of the Philistine diet in places), by an abandonment of the Philistine/Canaanite custom of having highly decorated pottery, and by the practice of circumcision. The Israelite ethnic identity had originated, not from the Exodus and a subsequent conquest, but from a transformation of the existing Canaanite-Philistine cultures.[25]

These surveys revolutionized the study of early Israel. The discovery of the remains of a dense network of highland villages – all apparently established within the span of few generations – indicated that a dramatic social transformation had taken place in the central hill country of Canaan around 1200 BCE. There was no sign of violent invasion or even the infiltration of a clearly defined ethnic group. Instead, it seemed to be a revolution in lifestyle. In the formerly sparsely populated highlands from the Judean hills in the south to the hills of Samaria in the north, far from the Canaanite cities that were in the process of collapse and disintegration, about two-hundred fifty hilltop communities suddenly sprang up. Here were the first Israelites.[26]

Modern scholars therefore see Israel arising peacefully and internally from existing people in the highlands of Canaan.[27]

Iron Age II (950–587 BCE)[edit]

Unusually favourable climatic conditions in the first two centuries of Iron Age II brought about an expansion of population, settlements and trade throughout the region.[28] In the central highlands this resulted in unification in a kingdom with the city of Samaria as its capital,[28] possibly by the second half of the 10th century BCE when an inscription of the Egyptian pharaoh Shoshenq I, the biblical Shishak, records a series of campaigns directed at the area.[29] Israel had clearly emerged by the middle of the 9th century BCE, when the Assyrian king Shalmaneser III names "Ahab the Israelite" among his enemies at the battle of Qarqar (853). At this time Israel was apparently engaged in a three-way contest with Damascus and Tyre for control of the Jezreel Valley and Galilee in the north, and with Moab, Ammon and Aram Damascus in the east for control of Gilead;[28] the Mesha Stele (c. 830), left by a king of Moab, celebrates his success in throwing off the oppression of the "House of Omri" (i.e., Israel). It bears what is generally thought to be the earliest extra-biblical reference to the name Yahweh.[30] A century later Israel came into increasing conflict with the expanding Neo-Assyrian Empire, which first split its territory into several smaller units and then destroyed its capital, Samaria (722). Both the biblical and Assyrian sources speak of a massive deportation of people from Israel and their replacement with settlers from other parts of the empire – such population exchanges were an established part of Assyrian imperial policy, a means of breaking the old power structure – and the former Israel never again became an independent political entity.[31]

Judah emerged as an operational kingdom somewhat later than Israel, probably during the 9th century BCE, but the subject is one of considerable controversy.[32] There are indications that during the 10th and 9th centuries BCE, the southern highlands had been divided between a number of centres, none with clear primacy.[33] During the reign of Hezekiah, between c. 715 and 686 BCE, a notable increase in the power of the Judean state can be observed.[34] This is reflected in archaeological sites and findings, such as the Broad Wall; a defensive city wall in Jerusalem; and the Siloam tunnel, an aqueduct designed to provide Jerusalem with water during an impending siege by the Neo-Assyrian Empire led by Sennacherib; and the Siloam inscription, a lintel inscription found over the doorway of a tomb, has been ascribed to comptroller Shebna. LMLK seals on storage jar handles, excavated from strata in and around that formed by Sennacherib's destruction, appear to have been used throughout Sennacherib's 29-year reign, along with bullae from sealed documents, some that belonged to Hezekiah himself and others that name his servants.[35]

In the 7th century Jerusalem grew to contain a population many times greater than earlier and achieved clear dominance over its neighbours.[36] This occurred at the same time that Israel was being destroyed by the Neo-Assyrian Empire, and was probably the result of a cooperative arrangement with the Assyrians to establish Judah as an Assyrian vassal state controlling the valuable olive industry.[36] Judah prospered as a vassal state (despite a disastrous rebellion against Sennacherib), but in the last half of the 7th century BCE, Assyria suddenly collapsed, and the ensuing competition between Egypt and the Neo-Babylonian Empire for control of the land led to the destruction of Judah in a series of campaigns between 597 and 582.[36]

Babylonian period[edit]

Babylonian Judah suffered a steep decline in both economy and population[37] and lost the Negev, the Shephelah, and part of the Judean hill country, including Hebron, to encroachments from Edom and other neighbours.[38] Jerusalem, while probably not totally abandoned, was much smaller than previously, and the town of Mizpah in Benjamin in the relatively unscathed northern section of the kingdom became the capital of the new Babylonian province of Yehud Medinata.[39] (This was standard Babylonian practice: when the Philistine city of Ashkalon was conquered in 604, the political, religious and economic elite [but not the bulk of the population] was banished and the administrative centre shifted to a new location).[40] There is also a strong probability that for most or all of the period the temple at Bethel in Benjamin replaced that at Jerusalem, boosting the prestige of Bethel's priests (the Aaronites) against those of Jerusalem (the Zadokites), now in exile in Babylon.[41]

The Babylonian conquest entailed not just the destruction of Jerusalem and its temple, but the liquidation of the entire infrastructure which had sustained Judah for centuries.[42] The most significant casualty was the state ideology of "Zion theology,"[43] the idea that the god of Israel had chosen Jerusalem for his dwelling-place and that the Davidic dynasty would reign there forever.[44] The fall of the city and the end of Davidic kingship forced the leaders of the exile community – kings, priests, scribes and prophets – to reformulate the concepts of community, faith and politics.[45] The exile community in Babylon thus became the source of significant portions of the Hebrew Bible: Isaiah 40–55; Ezekiel; the final version of Jeremiah; the work of the hypothesized priestly source in the Pentateuch; and the final form of the history of Israel from Deuteronomy to 2 Kings.[46] Theologically, the Babylonian exiles were responsible for the doctrines of individual responsibility and universalism (the concept that one god controls the entire world) and for the increased emphasis on purity and holiness.[46] Most significantly, the trauma of the exile experience led to the development of a strong sense of Hebrew identity distinct from other peoples,[47] with increased emphasis on symbols such as circumcision and Sabbath-observance to sustain that distinction.[48]

The concentration of the biblical literature on the experience of the exiles in Babylon disguises the fact that the great majority of the population remained in Judah; for them, life after the fall of Jerusalem probably went on much as it had before.[49] It may even have improved, as they were rewarded with the land and property of the deportees, much to the anger of the community of exiles remaining in Babylon.[50] The assassination around 582 of the Babylonian governor by a disaffected member of the former royal House of David provoked a Babylonian crackdown, possibly reflected in the Book of Lamentations, but the situation seems to have soon stabilised again.[51] Nevertheless, those unwalled cities and towns that remained were subject to slave raids by the Phoenicians and intervention in their internal affairs by Samaritans, Arabs, and Ammonites.[52]

Persian period[edit]

When Babylon fell to the Persian Cyrus the Great in 539 BCE, Judah (or Yehud medinata, the "province of Yehud") became an administrative division within the Persian empire. Cyrus was succeeded as king by Cambyses, who added Egypt to the empire, incidentally transforming Yehud and the Philistine plain into an important frontier zone. His death in 522 was followed by a period of turmoil until Darius the Great seized the throne in about 521. Darius introduced a reform of the administrative arrangements of the empire including the collection, codification and administration of local law codes, and it is reasonable to suppose that this policy lay behind the redaction of the Jewish Torah.[53] After 404 the Persians lost control of Egypt, which became Persia's main rival outside Europe, causing the Persian authorities to tighten their administrative control over Yehud and the rest of the Levant.[54] Egypt was eventually reconquered, but soon afterward Persia fell to Alexander the Great, ushering in the Hellenistic period in the Levant.

Yehud's population over the entire period was probably never more than about 30,000 and that of Jerusalem no more than about 1,500, most of them connected in some way to the Temple.[55] According to the biblical history, one of the first acts of Cyrus, the Persian conqueror of Babylon, was to commission Jewish exiles to return to Jerusalem and rebuild their Temple, a task which they are said to have completed c. 515.[56] Yet it was probably not until the middle of the next century, at the earliest, that Jerusalem again became the capital of Judah.[57] The Persians may have experimented initially with ruling Yehud as a Davidic client-kingdom under descendants of Jehoiachin,[58] but by the mid–5th century BCE, Yehud had become, in practice, a theocracy, ruled by hereditary high priests,[59] with a Persian-appointed governor, frequently Jewish, charged with keeping order and seeing that taxes (tribute) were collected and paid.[60] According to the biblical history, Ezra and Nehemiah arrived in Jerusalem in the middle of the 5th century BCE, the former empowered by the Persian king to enforce the Torah, the latter holding the status of governor with a royal commission to restore Jerusalem's walls.[61] The biblical history mentions tension between the returnees and those who had remained in Yehud, the returnees rebuffing the attempt of the "peoples of the land" to participate in the rebuilding of the Temple; this attitude was based partly on the exclusivism that the exiles had developed while in Babylon and, probably, also partly on disputes over property.[62] During the 5th century BCE, Ezra and Nehemiah attempted to re-integrate these rival factions into a united and ritually pure society, inspired by the prophecies of Ezekiel and his followers.[63]

The Persian era, and especially the period between 538 and 400 BCE, laid the foundations for the unified Judaic religion and the beginning of a scriptural canon.[64] Other important landmarks in this period include the replacement of Hebrew as the everyday language of Judah by Aramaic (although Hebrew continued to be used for religious and literary purposes)[65] and Darius's reform of the empire's bureaucracy, which may have led to extensive revisions and reorganizations of the Jewish Torah.[53] The Israel of the Persian period consisted of descendants of the inhabitants of the old kingdom of Judah, returnees from the Babylonian exile community, Mesopotamians who had joined them or had been exiled themselves to Samaria at a far earlier period, Samaritans, and others.[66]

Hellenistic period[edit]

The beginning of the Hellenistic Period is marked by the conquest of Alexander the Great (333 BCE). When Alexander died in 323, he had no heirs that were able to take his place as ruler of his empire, so his generals divided the empire among themselves.[67] Ptolemy I asserted himself as the ruler of Egypt in 322 and seized Yehud Medinata in 320, but his successors lost it in 198 to the Seleucids of Syria. At first, relations between Seleucids and Jews were cordial, but the attempt of Antiochus IV Epiphanes (174–163) to impose Hellenic cults on Judea sparked the Maccabean Revolt that ended in the expulsion of the Seleucids and the establishment of an independent Jewish kingdom under the Hasmonean dynasty. Some modern commentators see this period also as a civil war between orthodox and hellenized Jews.[68][69] Hasmonean kings attempted to revive the Judah described in the Bible: a Jewish monarchy ruled from Jerusalem and including all territories once ruled by David and Solomon. In order to carry out this project, the Hasmoneans forcibly converted one-time Moabites, Edomites, and Ammonites to Judaism, as well as the lost kingdom of Israel.[70] Some scholars argue that the Hasmonean dynasty institutionalized the final Jewish biblical canon.[71]

Ptolemaic rule[edit]

Ptolemy I took control of Egypt in 322 BCE after the death of Alexander the Great. He also took control of Yehud Medinata in 320 because he was very aware that it was a great place to attack Egypt from and was also a great defensive position. However, there were others who also had their eyes on that area. Another former general, Antigonus Monophthalmus, had driven out the satrap of Babylon, Seleucus, in 317 and continued on towards the Levant. Seleucus found refuge with Ptolemy and they both rallied troops against Antigonus' son Demetrius, since Antigonus had retreated back to Asia Minor. Demetrius was defeated at the battle of Gaza and Ptolemy regained control of Yehud Medinata. However, not soon after this Antigonus came back and forced Ptolemy to retreat back to Egypt. This went on until the Battle of Ipsus in 301 where Seleucus' armies defeated Antigonus. Seleucus was given the areas of Syria and Palestine, but Ptolemy would not give up those lands, causing the Syrian Wars between the Ptolemies and Seleucids. Not much is known about the happenings of those in Yehud Medinata from the time of Alexander's death until the Battle of Ipsus due to the frequent battles.[72] At first, the Jews were content with Ptolemy's rule over them. His reign brought them peace and economic stability. He also allowed them to keep their religious practices, so long as they paid their taxes and didn't rebel.[73] After Ptolemy I came Ptolemy II Philadelphus, who was able to keep the territory of Yehud Medinata and brought the dynasty to the peak of its power. He was victorious in both the first and second Syrian Wars, but after trying to end the conflict with the Seleucids by arranging a marriage between his daughter Berenice and the Seleucid king Antiochus II, he died. The arranged marriage did not work and Berenice, Antiochus, and their child were killed from an order of Antiochus' former wife. This was one of the reasons for the third Syrian War. Before all of this, Ptolemy II fought and defeated the Nabataeans. In order to enforce his hold on them, he reinforced many cities in Palestine and built new ones. As a result of this, more Greeks and Macedonians moved to those new cities and brought over their customs and culture, or Hellenism. The Ptolemaic Rule also gave rise to 'tax farmers'. These were the bigger farmers who collected the high taxes of the smaller farmers. These farmers made a lot of money off of this, but it also put a rift between the aristocracy and everyone else. During the end of the Third Syrian War, the high priest Onias II would not pay the tax to the Ptolemy III Euergetes. It is thought that this shows a turning point in the Jew's support of the Ptolemies.[74] The Fourth and Fifth Syrian Wars marked the end of the Ptolemaic control of Palestine. Both of these wars hurt Palestine more than the previous three. That and the combination of the ineffective rulers Ptolemy IV Philopater and Ptolemy V and the might of the large Seleucid army ended the century-long rule of the Ptolemaic Dynasty over Palestine.[75]

Seleucid rule and the Maccabean Revolt[edit]

The Seleucid Rule of Palestine began in 198 BCE under Antiochus III. He, like the Ptolemies, let the Jews keep their religion and customs and even went so far as to encourage the rebuilding of the temple and city after they welcomed him so warmly into Jerusalem.[76] However, Antiochus owed the Romans a great deal of money. In order to raise this money, he decided to rob a temple. The people at the temple of Bel in Elam were not pleased, so they killed Antiochus and everyone helping him in 187 BCE. He was succeeded by his son Seleucus IV Philopater. He simply defended the area of Palestine from Ptolemy V before being murdered by his minister in 175. His brother Antiochus IV Epiphanes took his place. Before he killed the king, the minister Heliodorus had tried to steal the treasures the temple in Jerusalem. He was informed of this knowledge by a rival of the current High Priest Onias III. Heliodorus was not allowed into the temple, but it required Onias to go explain to the king why one of his ministers was denied access somewhere. In his absence, his rivals put up a new high priest. Onias' brother Jason (a Hellenized version of Joshua) took his place.[77] Now with Jason as high priest and Antiochus IV as king, many Jews adopted Hellenistic ways. Some of these ways, as stated in the Book of 1 Maccabees, were the building of a gymnasium, finding ways to hide their circumcision, and just generally not abiding by the holy covenant.[78] This led to the beginning of the Maccabean Revolt.

According to the Book of Maccabees, many Jews were not happy with the way Hellenism had spread into Judea. Some of these Jews were Mattathias and his sons.[78] Mattathias refused to offer sacrifice when the king told him to. He killed a Jew who was going to do so as well as the king's representative. Because of this, Mattathias and his sons had to flee. This marks the true beginning of the Maccabean Revolt. Judas Maccabeus became the leader of the rebels. He proved to be a successful general, defeating an army lead by Apollonius. They started to catch the attention of King Antiochus IV in 165, who told his chancellor to put an end to the revolt. The chancellor, Lysias, sent three generals to do just that, but they were all defeated by the Maccabees. Soon after, Lysias went himself but, according to 1 and 2 Maccabees he was defeated. There is evidence to show that it was not that simple and that there was negotiation, but Lysias still left. After the death of Antiochus IV in 164, his son, Antiochus V, gave the Jews religious freedom. Lysias claimed to be his regent. Around this time was the re-dedication of the temple. During the siege of the Acra, one of Judas' brothers, Eleazor, was killed. The Maccabees had to retreat back to Jerusalem, where they should have been beaten badly. However, Lysias had to pull out because of a contradiction of who was to be regent for Antiochus V. Shortly after, both were killed by Demetrius I Soter who became the new king. The new high priest, Alcimus, had come to Jerusalem with the company of an army lead by Bacchides.[79] A group of scribes called the Hasideans asked him for his word that he would not harm anyone. He agreed, but killed sixty of them.[80] Around this time Judas was able to make a treaty with the Romans. Soon after this, Judas was killed in Jerusalem fighting Bacchides' army. His brother Jonathan succeeded him. For eight years, Jonathan didn't do much. However, in 153 the Seleucid Empire started to face some problems. Jonathan used this chance to exchange his services of troops for Demetrius so that he could take back Jerusalem. He was appointed high priest by Alexander Balas for the same thing. When conflicts between Egypt and the Seleucids arose, Jonathan occupied the Acra. As conflicts over the throne arose, he completely took control of the Acra. But in 142 he was killed.[81] His brother Simon took his place.[82]

The Hasmonean Dynasty[edit]

Simon was nominated for the title of high priest, general, and leader by a "great assembly". He reached out to Rome to have them guarantee that Judea would be an independent land. Antiochus VII wanted the cities of Gadara, Joppa, and the Acra back. He also wanted a very large tribute. Simon only wanted to pay a fraction of that for only two of the cites, so Antiochus sent his general Cendebaeus to attack. The general was killed and the army fled. Simon and two of his sons were killed in a plot to overthrow the Hasmoneans. His last remaining son, John Hyrcanus, was supposed to be killed as well, but he was informed of the plan and rushed to Jerusalem to keep it safe. Hyrcanus had many issues to deal with as the new high priest. Antiochus invaded Judea and besieged Jerusalem in 134 BCE. Due to lack of food, Hyrcanus had to make a deal with Antiochus. He had to pay a large sum of money, tear down the walls of the city, acknowledge Seleucid power over Judea, and help the Seleucids fight against the Parthians. Hyrcanus agreed to this, but the war against the Parthians didn't work and Antiochus died in 128. Hyrcanus was able to take back Judea and keep his power. John Hyrcanus also kept good relations with the Roman and the Egyptians, owing to the large number of Jews living there, and conquered Transjordan, Samaria,[83] and Idumea (also known as Edom).[84][85] Aristobulus I was the first Hasmonean priest-king. He defied his father's wishes that his mother should take over the government and instead had her and all of his brothers except for one thrown in prison. The one not thrown in prison was later killed on his orders. The most significant thing he did during his one-year-reign was conquer most of Galilee. After his death, he was succeeded by his brother Alexander Jannaeus, who was only concerned with power and conquest. He also married his brother's widow, showing little respect for Jewish law. His first conquest was Ptolemais. The people called to Ptolemy IX for aid, as he was in Cyprus. However, it was his mother, Cleopatra III, who came to help Alexander and not her son. Alexander was not a popular ruler. This caused a civil war in Jerusalem that lasted for six years. After Alexander Jannaeus' death, his widow became ruler, but not high priest. The end of the Hasmonean Dynasty was in 63 when the Romans came at the request of the current priest-king Aristobulus II and his competitor Hyrcanus II. In 63 BCE the Roman general Pompey conquered Jerusalem and the Romans put Hyrcanus II up as high priest, but Judea became a client-kingdom of Rome. The dynasty came to an end in 40 BCE when Herod was crowned king of Judah by the Romans. With their help, Herod had seized Jerusalem by 37.[86]

The Herodean Dynasty[edit]

In 40–39 BCE, Herod the Great was appointed King of the Jews by the Roman Senate, and in 6 CE the last ethnarch of Judea was deposed by the emperor Augustus, his territories combined with Idumea and Samaria and annexed as Iudaea Province under direct Roman administration.[87]

Religion[edit]

Henotheism[edit]

Henotheism is defined in the dictionary as adherence to one god out of several.[88] Many scholars believe that before monotheism in ancient Israel came a transitional period in between polytheism and monotheism. In this transitional period many followers of the Israelite religion worshiped the god Yahweh but did not deny the existence of other deities accepted throughout the region.[89] Some scholars attribute this henotheistic period to influences from Mesopotamia. There are strong arguments that Mesopotamia, particularly Assyria shared the concept of the cult of Ashur with Israel.[90] This concept entailed adopting the gods of other cultures into their pantheon, with Ashur as the supreme god of all the others.[90] This concept is believed to have influenced the transitional period in Israelite religion in which many people were henotheists. Israelite religion shares many characteristics with Canaanite religion, which itself was formed with influence from Mesopotamian religious traditions.[91] Using Canaanite religion as a base was natural due to the fact that the Canaanite culture inhabited the same region prior to the emergence of Israelite culture.[92] Canaanite religion was a polytheistic religion in which many gods represented unique concepts. Many scholars agree that the Israelite god of Yahweh was adopted from the Canaanite god El.[92] El was the creation god and as such it makes sense for the Israelite supreme god to have El's characteristics. Monotheism in the region of ancient Israel and Judah did not take hold over night and during the intermediate stages most people are believed to have been henotheistic.[91] Before the emergence of Yahweh as the patron god of the region of ancient Israel and Judah not all worshiped him alone, or even at all. The word "Israel" is based on the name El rather than Yahweh.[93][94][95]

During this intermediate period of henotheism many families worshiped different gods. Religion was very much centered around the family, as opposed to the community. People sparsely populated the region of Israel and Judah during the time of Moses. As such many different areas worshiped different gods, due to social isolation.[96] It was not until later on in Israelite history that people started to worship Yahweh alone and fully convert to monotheistic values. That switch occurred with the growth of power and influence of the Israelite kingdom and its rulers and can be read about further in the Iron Age Yahwism section below. Evidence from the bible suggests that henotheism did exist: "They [the Hebrews] went and served alien gods and paid homage to them, gods of whom they had no experience and whom he [Yahweh] did not allot to them" (Deut. 29.26). Many believe that this quote goes to show that the early Israelite kingdom followed similar traditions as ancient Mesopotamia, where each major urban center had a supreme god. Each culture then embraced their patron god but did not deny the existence of other cultures' patron gods. In Assyria, the patron god was Ashur, and in ancient Israel, it was Yahweh; however, both Israelite and Assyrian cultures recognized each other's deities during this period.[96]

Some scholars have used the Bible as evidence to argue that most of the people alive during the events recounted in the Old Testament, including Moses, were most likely henotheists. There are many quotes from the Old Testament support this point of view. One quote from Jewish and Christian tradition that supports this claim is the first commandment which in its entirety reads "I am the LORD your God, who brought you out of the land of Egypt, out of the house of bondage. You shall have no other gods before me."[97] This quote does not deny the existence of other gods; it merely states that Jews and Christians should consider Yahweh or God the supreme god, incomparable to other supernatural beings. Some scholars attribute the concept of angels and demons found in Judaism and Christianity to the tradition of henotheism. Instead of completely getting rid of the concept of other supernatural beings, these religions changed former deities into angels and demons.[91] Yahweh became the supreme god governing angels, demons and humans, with angels and demons considered more powerful than the average human. This tradition of believing in multiple forms of supernatural beings is attributed by many to the traditions of ancient Mesopotamia and Canaan and their pantheons of gods. Earlier influences from Mesopotamia and Canaan were important in creating the foundation of Israelite religion consistent with the Kingdoms of ancient Israel and Judah, and have since left lasting impacts on some of the biggest and most widespread religions in our world today.

Iron Age Yahwism[edit]

The religion of the Israelites of Iron Age I, like the Ancient Canaanite religion from which it evolved and other religions of the ancient Near East, was based on a cult of ancestors and worship of family gods (the "gods of the fathers").[98][99] With the emergence of the monarchy at the beginning of Iron Age II the kings promoted their family god, Yahweh, as the god of the kingdom, but beyond the royal court, religion continued to be both polytheistic and family-centered.[100] The major deities were not numerous – El, Asherah, and Yahweh, with Baal as a fourth god, and perhaps Shamash (the sun) in the early period.[101] At an early stage El and Yahweh became fused and Asherah did not continue as a separate state cult,[101] although she continued to be popular at a community level until Persian times.[102]

Yahweh, the national god of both Israel and Judah, seems to have originated in Edom and Midian in southern Canaan and may have been brought to Israel by the Kenites and Midianites at an early stage.[103] There is a general consensus among scholars that the first formative event in the emergence of the distinctive religion described in the Bible was triggered by the destruction of Israel by Assyria in c. 722 BCE. Refugees from the northern kingdom fled to Judah, bringing with them laws and a prophetic tradition of Yahweh. This religion was subsequently adopted by the landowners of Judah, who in 640 BCE placed the eight-year-old Josiah on the throne. Judah at this time was a vassal state of Assyria, but Assyrian power collapsed in the 630s, and around 622 Josiah and his supporters launched a bid for independence expressed as loyalty to "Yahweh alone".

The Babylonian exile and Second Temple Judaism[edit]

According to the Deuteronomists, as scholars call these Judean nationalists, the treaty with Yahweh would enable Israel's god to preserve both the city and the king in return for the people's worship and obedience. The destruction of Jerusalem, its Temple, and the Davidic dynasty by Babylon in 587/586 BCE was deeply traumatic and led to revisions of the national mythos during the Babylonian exile. This revision was expressed in the Deuteronomistic history, the books of Joshua, Judges, Samuel and Kings, which interpreted the Babylonian destruction as divinely-ordained punishment for the failure of Israel's kings to worship Yahweh to the exclusion of all other deities.[104]

The Second Temple period (520 BCE – 70 CE) differed in significant ways from what had gone before.[105] Strict monotheism emerged among the priests of the Temple establishment during the seventh and sixth centuries BCE, as did beliefs regarding angels and demons.[106] At this time, circumcision, dietary laws, and Sabbath-observance gained more significance as symbols of Jewish identity, and the institution of the synagogue became increasingly important, and most of the biblical literature, including the Torah, was written or substantially revised during this time.[107]

See also[edit]

- Biblical archaeology

- Canaan#History

- Chronology of the Bible

- Early Israelite campaigns

- Habiru

- History of Israel

- History of Palestine

- History of the Jews in Egypt

- History of the Jews in Iran

- History of the Jews in the Roman Empire

- History of the Levant

- History of the Southern Levant

- Intertestamental period

- Israelites

- Jews

- Jewish diaspora

- Kings of Israel and Judah

- Kings of Judah

- Lachish relief

- Old Testament

- Pre-history of the Southern Levant

- Shasu

- Tanakh

- United Monarchy

References[edit]

Citations[edit]

- ^ The Lester and Sally Entin Faculty of Humanities,Megiddo. in Archaeology & History of the Land of the Bible International MA in Ancient Israel Studies, Tel Aviv University: "...Megiddo has...a fascinating picture of state-formation and social evolution in the Bronze Age (ca. 3500-1150 B.C.) and Iron Age (ca. 1150-600 B.C.)..."

- ^ Finkelstein, Israel, (2019).First Israel, Core Israel, United (Northern) Israel, in Near Eastern Archaeology 82.1 (2019), p. 8: "...The late Iron I system came to an end during the tenth century BCE..."

- ^ Finkelstein, Israel, and Eli Piasetzky, 2010. "The Iron I/IIA Transition in the Levant: A Reply to Mazar and Bronk Ramsey and a New Perspective", in Radiocarbon, Vol 52, No. 4, The Arizona Board of Regents in behalf of the University of Arizona, pp. 1667 and 1674: "The Iron I/IIA transition occurred during the second half of the 10th century...We propose that the late Iron I cities came to an end in a gradual process and interpret this proposal with Bayesian Model II...The process results in a transition date of 915-898 BCE (68% range), or 927-879 BCE (95% range)..."

- ^ King & Stager 2001, p. xxiii.

- ^ Jerusalem in the First Temple period (c.1000-586 B.C.E.), Ingeborg Rennert Center for Jerusalem Studies, Bar-Ilan University, last modified 1997, accessed 11 February 2019

- ^ Miller 1986, p. 36.

- ^ Coogan 1998, pp. 4–7.

- ^ Finkelstein 2001, p. 78.

- ^ a b Killebrew 2005, pp. 38–39.

- ^ Cahill in Vaughn 1992, pp. 27–33.

- ^ Kuhrt 1995, p. 317.

- ^ Killebrew 2005, pp. 10–16.

- ^ Golden 2004b, pp. 61–62.

- ^ McNutt 1999, p. 47.

- ^ Golden 2004a, p. 155.

- ^ Stager in Coogan 1998, p. 91.

- ^ Dever 2003, p. 206.

- ^ McNutt 1999, p. 35.

- ^ McNutt 1999, pp. 46–47.

- ^ McNutt 1999, p. 69.

- ^ Miller 1986, p. 72.

- ^ Killebrew 2005, p. 13.

- ^ Edelman in Brett 2002, pp. 46–47.

- ^ Finkelstein and Silberman (2001), p. 107

- ^ Avraham Faust, "How Did Israel Become a People? The Genesis of Israelite Identity", Biblical Archaeology Review 201 (2009): 62–69, 92–94.

- ^ Finkelstein and Silberman (2001), p. 107.

- ^

Compare: Gnuse, Robert Karl (1997). No Other Gods: Emergent Monotheism in Israel. Journal for the study of the Old Testament: Supplement series. 241. Sheffield: A&C Black. p. 31. ISBN 9781850756576. Retrieved 2 June 2016.

Out of the discussions a new model is beginning to emerge, which has been inspired, above all, by recent archaeological field research. There are several variations in this new theory, but they share in common the image of an Israelite community which arose peacefully and internally in the highlands of Palestine.

- ^ a b c Thompson 1992, p. 408.

- ^ Mazar in Schmidt, p. 163.

- ^ Patrick D. Miller (2000). The Religion of Ancient Israel. Westminster John Knox Press. pp. 40–. ISBN 978-0-664-22145-4.

- ^ Lemche 1998, p. 85.

- ^ Grabbe 2008, pp. 225–26.

- ^ Lehman in Vaughn 1992, p. 149.

- ^ David M. Carr, Writing on the Tablet of the Heart: Origins of Scripture and Literature, Oxford University Press, 2005, 164.

- ^ "LAMRYEU-HNNYEU-OBD-HZQYEU".

- ^ a b c Thompson 1992, pp. 410–11.

- ^ Grabbe 2004, p. 28.

- ^ Lemaire in Blenkinsopp 2003, p. 291.

- ^ Davies 2009.

- ^ Lipschits 2005, p. 48.

- ^ Blenkinsopp in Blenkinsopp 2003, pp. 103–05.

- ^ Blenkinsopp 2009, p. 228.

- ^ Middlemas 2005, pp. 1–2.

- ^ Miller 1986, p. 203.

- ^ Middlemas 2005, p. 2.

- ^ a b Middlemas 2005, p. 10.

- ^ Middlemas 2005, p. 17.

- ^ Bedford 2001, p. 48.

- ^ Barstad 2008, p. 109.

- ^ Albertz 2003a, p. 92.

- ^ Albertz 2003a, pp. 95–96.

- ^ Albertz 2003a, p. 96.

- ^ a b Blenkinsopp 1988, p. 64.

- ^ Lipschits in Lipschits 2006, pp. 86–89.

- ^ Grabbe 2004, pp. 29–30.

- ^ Nodet 1999, p. 25.

- ^ Davies in Amit 2006, p. 141.

- ^ Niehr in Becking 1999, p. 231.

- ^ Wylen 1996, p. 25.

- ^ Grabbe 2004, pp. 154–55.

- ^ Soggin 1998, p. 311.

- ^ Miller 1986, p. 458.

- ^ Blenkinsopp 2009, p. 229.

- ^ Albertz 1994, pp. 437–38.

- ^ Kottsieper in Lipschits 2006, pp. 109–10.

- ^ Becking in Albertz 2003b, p. 19.

- ^ Jagersma, H. (1994). A history of Israel to Bar Kochba. SCM. p. 16. ISBN 033402577X. OCLC 906667007.

- ^ Weigel, David. "Hanukkah as Jewish civil war". Slate.com. Slate Magazine. Retrieved 15 August 2012.

- ^ "The Revolt of the Maccabees". Simpletoremember.com. Retrieved 15 August 2012.

- ^ Davies 1992, pp. 149–50.

- ^ Philip R. Davies in The Canon Debate, p. 50: "With many other scholars, I conclude that the fixing of a canonical list was almost certainly the achievement of the Hasmonean dynasty."

- ^ Jagersma, H. (1994). A history of Israel to Bar Kochba. SCM. pp. 17–18. ISBN 033402577X. OCLC 906667007.

- ^ Grabbe, Lester L. (1992). Judaism from Cyrus to Hadrian. Fortress Press. p. 216. OCLC 716308928.

- ^ Jagersma, H. (Hendrik) (1994). A history of Israel to Bar Kochba. SCM. pp. 22–29. ISBN 033402577X. OCLC 906667007.

- ^ Jagersma, H. (Hendrik) (1994). A history of Israel to Bar Kochba. SCM. pp. 29–35. ISBN 033402577X. OCLC 906667007.

- ^ Kosmin, Paul J. (2018). The land of the elephant kings : space, territory, and ideology in the Seleucid Empire. p. 154. ISBN 978-0674986886. OCLC 1028624877.

- ^ Pearlman, Moshe (1973). The Maccabees. Macmillan. OCLC 776163.

- ^ a b New American Bible. p. 521.

- ^ Jagersma, H. (Hendrik) (1994). A history of Israel to Bar Kochba. SCM. pp. 59–63. ISBN 033402577X. OCLC 906667007.

- ^ New American Bible. p. 532.

- ^ Jagersma, H. (Hendrik) (1994). A history of Israel to Bar Kochba. SCM. pp. 63–67. ISBN 033402577X. OCLC 906667007.

- ^ Jagersma, H. (Hendrik) (1994). A history of Israel to Bar Kochba. SCM. p. 79. ISBN 033402577X. OCLC 906667007.

- ^ On the destruction of the Samaritan temple on Mount Gerizim by John Hyrcanus, see for instance: Menahem Mor, "The Persian, Hellenistic and Hasmonean Period," in The Samaritans (ed. Alan D. Crown; Tübingen: Mohr-Siebeck, 1989) 1–18; Jonathan Bourgel (2016). "The Destruction of the Samaritan Temple by John Hyrcanus: A Reconsideration". Journal of Biblical Literature. 135 (153/3): 505. doi:10.15699/jbl.1353.2016.3129.

- ^ Berthelot, Katell (2017). In Search of the Promised Land?. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. pp. 240–41. doi:10.13109/9783666552526. ISBN 9783525552520.

- ^ Jagersma, H. (Hendrik) (1994). A history of Israel to Bar Kochba. SCM. pp. 80–85. ISBN 033402577X. OCLC 906667007.

- ^ Jagersma, H. (Hendrik) (1994). A history of Israel to Bar Kochba. SCM. pp. 87–102. ISBN 033402577X. OCLC 906667007.

- ^ Ben-Sasson 1976, p. 246.

- ^ "the definition of henotheism". www.dictionary.com. Retrieved 26 April 2019.

- ^ Taliaferro, Charles; Harrison, Victoria S.; Goetz, Stewart (2012). The Routledge Companion to Theism. Routledge.

- ^ a b Levine, Baruch (2005). "Assyrian Ideology and Israelite Monotheism". British Institute for the Study of Iraq. 67 (1): 411–27. JSTOR 4200589.

- ^ a b c Meek, Theophile James (1942). "Monotheism and the Religion of Israel". Journal of Biblical Literature. 61 (1): 21–43. doi:10.2307/3262264. JSTOR 3262264.

- ^ a b Dever, William (1987). "Archaeological Sources for the History of Palestine: The Middle Bronze Age: The Zenith of the Urban Canaanite Era". The Biblical Archaeologist. 50 (3): 149–77. doi:10.2307/3210059. JSTOR 3210059.

- ^ Coogan, Michael David; Coogan, Michael D. (2001). The Oxford History of the Biblical World. Oxford University Press. p. 54. ISBN 9780195139372. Retrieved 3 November 2019.

- ^ Smith, Mark S. (2002). The Early History of God: Yahweh and the Other Deities in Ancient Israel. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. p. 32. ISBN 9780802839725.

- ^ Giliad, Elon (20 April 2015). "Why Is Israel Called Israel?". Haaretz. Retrieved 3 November 2019.

- ^ a b Caquot, André (2000). "At the Origins of the Bible". Near Eastern Archaeology. 63 (4): 225–27. doi:10.2307/3210793. JSTOR 3210793.

- ^ "Catechism of the Catholic Church – The Ten Commandments". www.vatican.va. Retrieved 28 April 2019.

- ^ Tubbs, Jonathan (2006) "The Canaanites" (BBC Books)

- ^ Van der Toorn 1996, p. 4.

- ^ Van der Toorn 1996, pp. 181–82.

- ^ a b Smith 2002, p. 57.

- ^ Dever (2005), p.

- ^ Van der Toorn 1999, pp. 911–13.

- ^ Dunn and Rogerson, pp. 153–54

- ^ Avery Peck, p. 58

- ^ Grabbe (2004), pp. 243–44.

- ^ Avery Peck, p. 59

Bibliography[edit]

- Dever, William (2017). Beyond the Texts: An Archaeological Portrait of Ancient Israel and Judah. SBL Press. ISBN 9780884142171.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Albertz, Rainer (1994) [Vanderhoek & Ruprecht 1992]. A History of Israelite Religion, Volume I: From the Beginnings to the End of the Monarchy. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 9780664227197.

- Albertz, Rainer (1994) [Vanderhoek & Ruprecht 1992]. A History of Israelite Religion, Volume II: From the Exile to the Maccabees. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 9780664227203.

- Albertz, Rainer (2003a). Israel in Exile: The History and Literature of the Sixth Century B.C.E. Society of Biblical Literature. ISBN 9781589830554.

- Avery-Peck, Alan; et al., eds. (2003). The Blackwell Companion to Judaism. Blackwell. ISBN 9781577180593.

- Barstad, Hans M. (2008). History and the Hebrew Bible. Mohr Siebeck. ISBN 9783161498091.

- Becking, Bob (2003b). "Law as Expression of Religion (Ezra 7–10)". In Albertz, Rainer; Becking, Bob (eds.). Yahwism After the Exile: Perspectives on Israelite Religion in the Persian Era. Koninklijke Van Gorcum. ISBN 9789023238805.

- Bedford, Peter Ross (2001). Temple Restoration in Early Achaemenid Judah. Brill. ISBN 978-9004115095.

- Ben-Sasson, H.H. (1976). A History of the Jewish People. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-39731-6.

- Blenkinsopp, Joseph (1988). Ezra-Nehemiah: A Commentary. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780664221867.

- Blenkinsopp, Joseph (2003). "Bethel in the Neo-Babylonian Period". In Blenkinsopp, Joseph; Lipschits, Oded (eds.). Judah and the Judeans in the Neo-Babylonian Period. Eisenbrauns. ISBN 9781575060736.

- Blenkinsopp, Joseph (2009). Judaism, the First Phase: The Place of Ezra and Nehemiah in the Origins of Judaism. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802864505.

- Cahill, Jane M. (1992). "Jerusalem at the Time of the United Monarchy". In Vaughn, Andrew G.; Killebrew, Ann E. (eds.). Jerusalem in Bible and Archaeology: The First Temple Period. Sheffield. ISBN 9781589830660.

- Coogan, Michael D., ed. (1998). The Oxford History of the Biblical World. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195139372.

- Davies, Philip R. (1992). In Search of Ancient Israel. Sheffield. ISBN 9781850757375.

- Davies, Philip R. (2006). "The Origin of Biblical Israel". In Amit, Yaira; et al. (eds.). Essays on Ancient Israel in its Near Eastern Context: A Tribute to Nadav Na'aman. Eisenbrauns. ISBN 9781575061283.

- Davies, Philip R. (2009). "The Origin of Biblical Israel". Journal of Hebrew Scriptures. 9 (47). Archived from the original on 28 May 2008.

- Dever, William (2003). Who Were the Early Israelites and Where Did They Come From?. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802809759.

- Dever, William (2005). Did God Have a Wife?: Archaeology and Folk Religion in Ancient Israel. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802828521.

- Dunn, James D.G.; Rogerson, John William, eds. (2003). Eerdmans commentary on the Bible. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802837110.

- Edelman, Diana (2002). "Ethnicity and Early Israel". In Brett, Mark G. (ed.). Ethnicity and the Bible. Brill. ISBN 978-0391041264.

- Finkelstein, Israel; Silberman, Neil Asher (2001). The Bible Unearthed. ISBN 9780743223386.

- Gnuse, Robert Karl (1997). No Other Gods: Emergent Monotheism in Israel. Sheffield Academic Press. ISBN 9781850756576.

- Golden, Jonathan Michael (2004a). Ancient Canaan and Israel: An Introduction. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195379853.

- Golden, Jonathan Michael (2004b). Ancient Canaan and Israel: New Perspectives. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781576078976.

- Grabbe, Lester L. (2004). A History of the Jews and Judaism in the Second Temple Period. T&T Clark International. ISBN 9780567043528.

- Grabbe, Lester L., ed. (2008). Israel in Transition: From Late Bronze II to Iron IIa (c. 1250–850 B.C.E.). T&T Clark International. ISBN 9780567027269.

- Killebrew, Ann E. (2005). Biblical Peoples and Ethnicity: An Archaeological Study of Egyptians, Canaanites, and Early Israel, 1300–1100 B.C.E. Society of Biblical Literature. ISBN 9781589830974.

- King, Philip J.; Stager, Lawrence E. (2001). Life in Biblical Israel. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 978-0-664-22148-5.

Life in biblical Israel By Philip J. King, Lawrence E. Stager.

- Kottsieper, Ingo (2006). "And They Did Not Care to Speak Yehudit". In Lipschits, Oded; et al. (eds.). Judah and the Judeans in the Fourth Century B.C.E. Eisenbrauns. ISBN 9781575061306.

- Kuhrt, Amélie (1995). The Ancient Near East c. 3000–330 BCE. Routledge. ISBN 9780415167635.

- Lehman, Gunnar (1992). "The United Monarchy in the Countryside". In Vaughn, Andrew G.; Killebrew, Ann E. (eds.). Jerusalem in Bible and Archaeology: The First Temple Period. Sheffield. ISBN 9781589830660.

- Lemaire, André (2003). "Nabonidus in Arabia and Judea During the Neo-Babylonian Period". In Blenkinsopp, Joseph; Lipschits, Oded (eds.). Judah and the Judeans in the Neo-Babylonian Period. Eisenbrauns. ISBN 9781575060736.

- Lemche, Niels Peter (1998). The Israelites in History and Tradition. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 9780664227272.

- Lipschits, Oded (2005). The Fall and Rise of Jerusalem. Eisenbrauns. ISBN 9781575060958.

- Lipschits, Oded; Vanderhooft, David (2006). "Yehud Stamp Impressions in the Fourth Century B.C.E.". In Lipschits, Oded; et al. (eds.). Judah and the Judeans in the Fourth Century B.C.E. Eisenbrauns. ISBN 9781575061306.

- Mazar, Amihay (2007). "The Divided Monarchy: Comments on Some Archaeological Issues". In Schmidt, Brian B. (ed.). The Quest for the Historical Israel. Society of Biblical Literature. ISBN 9781589832770.

- McNutt, Paula (1999). Reconstructing the Society of Ancient Israel. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 9780664222659.

- Middlemas, Jill Anne (2005). The Troubles of Templeless Judah. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199283866.

- Miller, James Maxwell; Hayes, John Haralson (1986). A History of Ancient Israel and Judah. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 978-0-664-21262-9.

- Niehr, Herbert (1999). "Religio-Historical Aspects of the Early Post-Exilic Period". In Becking, Bob; Korpel, Marjo Christina Annette (eds.). The Crisis of Israelite Religion: Transformation of Religious Tradition in Exilic and Post-Exilic Times. Brill. ISBN 978-9004114968.

- Nodet, Étienne (1999) [Editions du Cerf 1997]. A Search for the Origins of Judaism: From Joshua to the Mishnah. Sheffield Academic Press. ISBN 9781850754459.

- Smith, Mark S.; Miller, Patrick D. (2002) [Harper & Row 1990]. The Early History of God. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802839725.

- Soggin, Michael J. (1998). An Introduction to the History of Israel and Judah. Paideia. ISBN 9780334027881.

- Stager, Lawrence E. (1998). "Forging an Identity: The Emergence of Ancient Israel". In Coogan, Michael D. (ed.). The Oxford History of the Biblical World. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195139372.

- Thompson, Thomas L. (1992). Early History of the Israelite People. Brill. ISBN 978-9004094833.

Early history of the Israelite people: from the written and archaeological ... By Thomas L. Thompson.

- Van der Toorn, Karel (1996). Family Religion in Babylonia, Syria, and Israel. Brill. ISBN 978-9004104105.

- Van der Toorn, Karel; Becking, Bob; Van der Horst, Pieter Willem (1999). Dictionary of Deities and Demons in the Bible (2d ed.). Koninklijke Brill. ISBN 9780802824912.

- Wylen, Stephen M. (1996). The Jews in the Time of Jesus: An Introduction. Paulist Press. ISBN 9780809136100.

An introduction to early Judaism By James C. VanderKam.

Further reading[edit]

This further reading section may contain inappropriate or excessive suggestions that may not follow Wikipedia's guidelines. Please ensure that only a reasonable number of balanced, topical, reliable, and notable further reading suggestions are given; removing less relevant or redundant publications with the same point of view where appropriate. Consider utilising appropriate texts as inline sources or creating a separate bibliography article. (August 2013) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

- Avery-Peck, Alan, and Neusner, Jacob, (eds), "The Blackwell Companion to Judaism (Blackwell, 2003)

- Marc Zvi, "The Creation of History in Ancient Israel" (Routledge, 1995), and also review at Dannyreviews.com

- Cook, Stephen L., "The social roots of biblical Yahwism" (Society of Biblical Literature, 2004)

- Day, John (ed), "In search of pre-exilic Israel: proceedings of the Oxford Old Testament Seminar" (T&T Clark International, 2004)

- Gravett, Sandra L., "An Introduction to the Hebrew Bible: A Thematic Approach" (Westminster John Knox Press, 2008)

- Grisanti, Michael A., and Howard, David M., (eds), "Giving the Sense:Understanding and Using Old Testament Historical Texts" (Kregel Publications, 2003)

- Hess, Richard S., "Israelite religions: an archaeological and biblical survey" Baker, 2007)

- Kavon, Eli, "Did the Maccabees Betray the Hanukka Revolution?", The Jerusalem Post, 26 December 2005

- Lemche, Neils Peter, "The Old Testament between theology and history: a critical survey" (Westminster John Knox Press, 2008)

- Levine, Lee I., "Jerusalem: portrait of the city in the second Temple period (538 B.C.E.–70 C.E.)" (Jewish Publication Society, 2002)

- Na'aman, Nadav, "Ancient Israel and its neighbours" (Eisenbrauns, 2005)

- Penchansky, David, "Twilight of the gods: polytheism in the Hebrew Bible" (Westminster John Knox Press, 2005)

- Provan, Iain William, Long, V. Philips, Longman, Tremper, "A Biblical History of Israel" (Westminster John Knox Press, 2003)

- Stephen C., "Images of Egypt in early biblical literature" (Walter de Gruyter, 2009)

- Sparks, Kenton L., "Ethnicity and identity in ancient Israel" (Eisenbrauns, 1998)

- Stackert, Jeffrey, "Rewriting the Torah: literary revision in Deuteronomy and the holiness code" (Mohr Siebeck, 2007)

- Vanderkam, James, "An introduction to early Judaism" (Eerdmans, 2001)