Mark Felt

Mark Felt | |

|---|---|

| |

| 2nd Associate Director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation | |

| In office May 3, 1972 – June 22, 1973 | |

| President | Richard Nixon |

| Preceded by | Clyde Tolson |

| Succeeded by | James B. Adams |

| Personal details | |

| Born | William Mark Felt August 17, 1913 Twin Falls, Idaho, U.S. |

| Died | December 18, 2008 (aged 95) Santa Rosa, California, U.S. |

| Spouse(s) | Audrey I. Robinson Felt (m. 1938; died 1984) |

| Children | 1 son, 1 daughter |

| Alma mater | University of Idaho (BA) George Washington University (JD) |

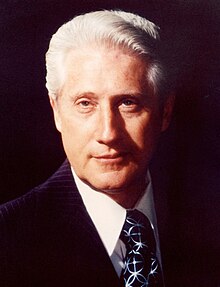

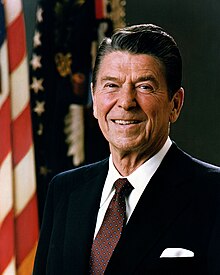

William Mark Felt Sr. (August 17, 1913 – December 18, 2008) was an American law enforcement officer who worked for the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) from 1942 to 1973 and was known for his role in the Watergate scandal. Felt was an FBI special agent who eventually rose to the position of Associate Director, the Bureau's second-highest-ranking post. Felt worked in several FBI field offices prior to his promotion to the Bureau's headquarters. In 1980 he was convicted of having violated the civil rights of people thought to be associated with members of the Weather Underground, by ordering FBI agents to break into their homes and search the premises as part of an attempt to prevent bombings. He was ordered to pay a fine, but was pardoned by President Ronald Reagan during his appeal.

In 2005, at age 91, Felt revealed that during his tenure as associate director of the FBI he had been the notorious anonymous source known as "Deep Throat" who provided The Washington Post reporters Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein with critical information about the Watergate scandal, which ultimately led to the resignation of President Richard Nixon in 1974. Though Felt's identity as Deep Throat was suspected, including by Nixon himself,[1] it had generally remained a secret for 30 years. Felt finally acknowledged that he was Deep Throat after being persuaded by his daughter to reveal his identity before his death.[2]

Felt published two memoirs: The FBI Pyramid in 1979 (updated in 2006), and A G-Man's Life, written with John O'Connor, in 2006. In 2012 the FBI released Felt's personnel file, covering the period from 1941 to 1978. It also released files pertaining to an extortion threat made against Felt in 1956.[3]

Early life and career[edit]

Born on August 17, 1913, in Twin Falls, Idaho,[4] Felt was the son of Rose R. Dygert and Mark Earl Felt, a carpenter and building contractor.[5] His paternal grandfather was a Free Will Baptist minister.[6] His maternal grandparents were born in Canada and Scotland. Through his maternal grandfather, Felt was descended from Revolutionary War general Nicholas Herkimer of New York.[6]

After graduating from Twin Falls High School in 1931, Felt attended the University of Idaho in Moscow.[7] He was a member and president of the Gamma Gamma chapter of the Beta Theta Pi fraternity,[8] and received a Bachelor of Arts degree in 1935.[7][9]

Felt then went to Washington, D.C., to work in the office of Democratic U.S. Senator James P. Pope. In 1938, Felt married Audrey Robinson of Gooding, Idaho, whom he had known when they were students at the University of Idaho.[10] She had come to Washington to work at the Bureau of Internal Revenue. Their wedding was officiated by the chaplain of the United States House of Representatives, the Rev. Sheara Montgomery.[11] Audrey died in 1984; she and Felt had two children, Joan and Mark.

Felt stayed on with Pope's successor in the Senate, David Worth Clark (D-Idaho).[12] He attended the George Washington University Law School at night, earning his law degree in 1940, and was admitted to the District of Columbia Bar in 1941.[13]

Upon graduation, Felt took a position at the Federal Trade Commission but did not enjoy his work. His workload was very light, and he was assigned to investigate whether a toilet paper brand, called "Red Cross", was misleading consumers into thinking it was endorsed by the American Red Cross. Felt wrote in his memoir:

My research, which required days of travel and hundreds of interviews, produced two definite conclusions:

1. Most people did use toilet tissue.

2. Most people did not appreciate being asked about it.

That was when I started looking for other employment.[14]

He applied for a job with the FBI in November 1941 and was accepted. His first day at the Bureau was January 26, 1942.

Early FBI years[edit]

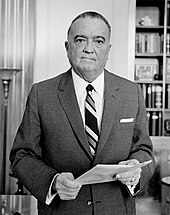

FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover often moved Bureau agents around so they would have wide experience in the field. This was typical of other agencies and corporations of the time. Felt observed that Hoover "wanted every agent to get into any field office at any time. Since he [Hoover] had never been transferred and did not have a family, he had no idea of the financial and personal hardship involved."[15]

After completing 16 weeks of training at the FBI Academy in Quantico, Virginia, and FBI Headquarters in Washington, Felt was assigned to Texas, spending three months each in the field offices in Houston and San Antonio. He returned to FBI Headquarters, where he was assigned to the Espionage Section of the Domestic Intelligence Division, tracking down spies and saboteurs during World War II. He worked on the Major Case Desk. His most notable work was on the "Peasant" case. Helmut Goldschmidt, operating under the codename "Peasant", was a German agent in custody in England. Under Felt's direction, his German masters were led to believe that "Peasant" had made his way to the United States, and thus were fed disinformation on Allied plans.[16]

The Espionage Section was abolished in May 1945 after V-E Day. After the war, Felt was assigned to the Seattle field office. After two years of general work, he spent two years as a firearms instructor and was promoted from agent to supervisor. Upon passage of the Atomic Energy Act and the creation of the United States Atomic Energy Commission, the Seattle office became responsible for completing background checks of workers at the Hanford plutonium plant near Richland, Washington. Felt oversaw those investigations.[17] In 1954 Felt returned briefly to Washington as an inspector's aide. Two months later, he was sent to New Orleans as Assistant Special Agent-in-Charge of the field office. When he was transferred to Los Angeles fifteen months later, he held the same rank there.[18]

Investigates organized crime[edit]

In 1956, Felt was transferred to Salt Lake City and promoted to Special Agent-in-Charge.[19] The Salt Lake City office included Nevada within its purview, and Felt oversaw some of the Bureau's earliest investigations into organized crime, assessing the mob's operations in the Reno and Las Vegas casinos.[18] (It was Hoover's, and therefore the Bureau's, official position at the time that there was no such thing as the Mob.[20]) In February 1958, Felt was assigned to Kansas City, Missouri (which he dubbed "the Siberia of field offices" in his memoir),[18] where he directed further investigations of organized crime. By this time, Hoover had come to believe in organized crime, in the wake of the famous Apalachin, New York, conclave of underworld bosses in November 1957.[21]

Middle career[edit]

Felt returned to Washington, D.C., in September 1962. As assistant to the bureau's assistant director in charge of the Training Division, Felt helped oversee the FBI Academy.[22] In November 1964, he was promoted to an Assistant Director of the Bureau, as Chief Inspector of the Bureau and Head of the Inspection Division.[23] This division oversaw compliance with Bureau regulations and conducted internal investigations.

On July 1, 1971, Felt was promoted by Hoover to Deputy Associate Director, assisting Associate Director Clyde Tolson.[24] Hoover's right-hand man for decades, Tolson was in failing health and unable to carry out his duties. Richard Gid Powers wrote that Hoover installed Felt to rein in William C. Sullivan's domestic spying operations, as Sullivan had been engaged in secret unofficial work for the White House.[25] In his memoir, Felt quoted Hoover as having said, "I need someone who can control Sullivan. I think you know he has been getting out of hand."[26] In his book, The Bureau, Ronald Kessler said that Felt "managed to please Hoover by being tactful with him and tough on agents".[27] Curt Gentry described Felt as "the director's latest fair-haired boy", who had "no inherent power" in his new post, the real number three being John P. Mohr.[28]

Weather Underground investigations[edit]

Among the criminal groups that the FBI investigated in the early 1970s was the Weather Underground. Their case was dismissed by the court because it concluded that the FBI had conducted illegal activities, including unauthorized wiretaps, break-ins, and mail interceptions. The lead federal prosecutor on the case, William C. Ibershof, claims that Felt and Attorney General John Mitchell initiated these illegal activities that tainted the investigation.[29]

After Hoover's death[edit]

Hoover died in his sleep and was found on the morning of May 2, 1972. Tolson was nominally in charge until the next day, when Nixon appointed L. Patrick Gray III as Acting FBI Director. Tolson submitted his resignation, which Gray accepted. Felt succeeded to Tolson's post as Associate Director, the number-two job in the Bureau.[30] Felt served as an honorary pallbearer at Hoover's funeral.[31] On the day of Hoover's death, Hoover's secretary for five decades, Helen Gandy, began destroying his files. She turned over twelve boxes of the "Official/Confidential" files to Felt on May 4, 1972. These contained 167 files and 17,750 pages, many of them containing derogatory information about individuals whom Hoover had investigated. He used this information as power over them. Felt stored the files in his office.

The existence of such files had long been rumored. Gray told the press that afternoon that "there are no dossiers or secret files. There are just general files and I took steps to preserve their integrity."[32] Felt earlier that day had told Gray, "Mr. Gray, the Bureau doesn't have any secret files", and later accompanied Gray to Hoover's office. They found Gandy boxing up papers. Felt said Gray "looked casually at an open file drawer and approved her work", though Gray would later deny he looked at anything. Gandy retained Hoover's "Personal File" and destroyed it.[32]

When Felt was called to testify in 1975 by the U.S. House about the destruction of Hoover's papers, he said, "There's no serious problems if we lose some papers. I don't see anything wrong and I still don't."[33] At the same hearing, Gandy claimed that she had destroyed Hoover's personal files only after receiving Gray's approval. In a letter submitted to the committee in rebuttal of Gandy's testimony, Gray vehemently denied ever giving such permission. Both Gandy's testimony and Gray's letter were included in the committee's final report.[33]

In his memoir, Felt expressed mixed feelings about Gray. He was the first person appointed as head of the FBI who had no experience in the agency, but he had experience in the Navy. While noting Gray did work hard, Felt was critical of how often he was away from FBI headquarters. Gray lived in Stonington, Connecticut, and commuted to Washington. He also visited all of the Bureau's field offices except Honolulu. His frequent absences led to the nickname "Three-Day Gray".[34] These absences, combined with Gray's hospitalization and recuperation from November 20, 1972, to January 2, 1973,[35] meant that Felt was effectively in charge for much of his final year at the Bureau. Bob Woodward wrote "Gray got to be director of the FBI and Felt did the work."[36] Felt wrote in his memoir:

The record amply demonstrates that President Nixon made Pat Gray the Acting Director of the FBI because he wanted a politician in J. Edgar Hoover's position who would convert the Bureau into an adjunct of the White House machine.[37]

Gray's defenders would later argue that Gray had practiced a management style that was different from that of Hoover. Gray's program of field office visits was something that Hoover had not done since his early years as director; some believed that Gray's visits helped raise the morale of the field agents. Gray's leadership style seemed to continue what he had learned in the US Navy, in which the executive officer concentrates on the basic operation of the ship, while the captain concentrates on its position and heading.[citation needed] Felt believed Gray's methods were an unnecessary distraction from the work of the FBI and showed a lack of leadership. He believed that he was not the only career manager at the FBI who disapproved of Gray's methods, particularly among those who had served under Hoover.[37]

Watergate[edit]

| Watergate scandal |

|---|

|

| Events |

| People |

|

Watergate burglars |

|

Judiciary |

|

Intelligence community |

As Associate Director, Felt saw everything compiled on Watergate before it was given to Gray. The Agent in Charge, Charles Nuzum, sent his findings to Investigative Division Head Robert Gebhardt, who passed the information on to Felt. From the day of the break-in, June 17, 1972, until the FBI investigation was mostly completed in June 1973, Felt was the key control point for FBI information. He had been among the first to learn of the investigation, being informed the morning of June 17.[38] Ronald Kessler, who spoke to former Bureau agents, reported that throughout the investigation, they "were amazed to see material in Woodward and Bernstein's stories lifted almost verbatim from their reports of interviews a few days or weeks earlier".[39]

"Deep Throat" informant[edit]

Bob Woodward first describes his source, nicknamed "Deep Throat", in All the President's Men, as a "source in the Executive Branch who had access to information at CRP (the Committee to Re-elect the President, Nixon's 1972 campaign organization), as well as at the White House".[40] In the book, Deep Throat is described as an "incurable gossip" who was "in a unique position to observe the Executive Branch", a man "whose fight had been worn out in too many battles".[41] Woodward had known the source before Watergate and had discussed politics and government with him.

In 2005 Woodward wrote that he first met Felt at the White House in 1969 or 1970. Woodward was working as an aide to Admiral Thomas Hinman Moorer, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and was delivering papers to the White House Situation Room. In his book The Secret Man, Woodward described Felt as a "tall man with perfectly combed gray hair ... distinguished looking" with a "studied air of confidence, even what might be called a command presence".[42] They stayed in touch and spoke on the telephone several times. When Woodward started working at the Washington Post, he phoned Felt on several occasions to ask for information for articles in the paper. Felt's information, taken on a promise that Woodward would never reveal its origin, was a source for a few stories, notably for an article on May 18, 1972, about Arthur Bremer, who shot George Wallace.

When the Watergate story broke, Woodward called on Felt. Felt told Woodward on June 19 that E. Howard Hunt, who had ties to Nixon, was involved: the telephone number of his White House office had been listed in the address book of one of the burglars. Initially, Woodward's source was known at the Post as "My Friend". Post editor Howard Simons tagged him as "Deep Throat", after the widely known porno film Deep Throat. According to Woodward, Simons thought of the term because Felt had been providing information on a deep background basis.

When Felt revealed his role in 2005, it was noted that "My Friend" has the same initial letters as "Mark Felt". Woodward's notes from interviewing Felt were marked "M.F.", which Woodward says was "not very good tradecraft".[43]

Code for contacting Woodward[edit]

Woodward explained that when he wanted to meet Deep Throat, he would move a flowerpot with a red flag on his apartment balcony; he lived at number 617, Webster House, 1718 P Street, Northwest. On occasions when Deep Throat wanted a meeting, he would circle the page number on page twenty of Woodward's copy of The New York Times (delivered to his building) and draw clock hands to signal the hour.[44]

Adrian Havill questioned these claims in his 1993 biography of Woodward and Bernstein. He said Woodward's balcony faced an interior courtyard and was not visible from the street. Woodward said that the courtyard had been bricked in since he lived there. Havill also said The Times was not delivered in copies marked by apartment, but Woodward and a former neighbor disputed this claim.[45]

Woodward said:

How [Felt] could have made a daily observation of my balcony is still a mystery to me. At the time, the back of my building was not enclosed so anyone could have driven in the back alley to observe my balcony. In addition, my balcony and the back of the apartment complex faced onto a courtyard or back area that was shared with a number of other apartment or office buildings in the area. My balcony could have been seen from dozens of apartments or offices. There were several embassies in the area. The Iraqi embassy was down the street, and I thought it possible that the FBI had surveillance or listening posts nearby. Could Felt have had the counterintelligence agents regularly report on the status of my flag and flowerpot? That seems unlikely, but not impossible.[46]

Haldeman informs Nixon about Felt's leaks[edit]

Days after the break-in, Nixon and White House chief of staff H. R. Haldeman talked about putting pressure on the FBI to slow down the investigation. The District of Columbia police had called in the FBI because they found the burglars had wiretapping equipment. Wiretapping is a crime investigated by the FBI. Haldeman told President Nixon on June 23, 1972, that Felt would "want to cooperate because he's ambitious".[47] These tapes were not declassified and revealed for some time.

Haldeman later initially suspected lower-level FBI agents, including Angelo Lano, of speaking to the Post.[48] But in a taped conversation on October 19, 1972, Haldeman told the president that sources had said that Felt was speaking to the press.

You can't say anything about this because it will screw up our source and there's a real concern. Mitchell is the only one who knows about this and he feels strongly that we better not do anything because ... if we move on him, he'll go out and unload everything. He knows everything that's to be known in the FBI. He has access to absolutely everything.[49]

Haldeman also said that he had spoken to White House counsel John W. Dean about punishing Felt, but Dean said Felt had committed no crime and could not be prosecuted.

When Acting FBI Director Gray returned from his sick leave in January 1973, he confronted Felt about being the source for Woodward and Bernstein. Gray said he had defended Felt to Attorney General Richard G. Kleindienst: "You know, Mark, Dick Kleindienst told me I ought to get rid of you. He says White House staff members are concerned that you are the FBI source of leaks to Woodward and Bernstein".[35] Felt replied, "Pat, I haven't leaked anything to anybody."[35] Gray told Felt:

I told Kleindienst that you've worked with me in a very competent manner and I'm convinced that you are completely loyal. I told him I was not going to move you out. Kleindienst told me, "Pat, I love you for that."[35]

Nixon passes over Felt again[edit]

On February 17, 1973, Nixon nominated Gray as Hoover's permanent replacement as Director.[50] Until then, Gray had been in limbo as Acting Director. In another taped conversation on February 28, Nixon spoke to Dean about Felt's acting as an informant, and mentioned that he had never met him. Gray was forced to resign on April 27, after it was revealed that he had destroyed a file that had been in the White House safe of E. Howard Hunt.[51] Gray recommended Felt as his successor.

The day Gray resigned, Kleindienst spoke to Nixon, urging him to appoint Felt as head of the FBI. Nixon instead appointed William Ruckelshaus as Acting Director. Stanley Kutler reported that Nixon said, "I don't want him. I can't have him. I just talked to Bill Ruckelshaus and Bill is a Mr. Clean and I want a fellow in there that is not part of the old guard and that is not part of that infighting in there."[52] On another White House tape, from May 11, 1973, Nixon and White House Chief of Staff, Alexander Haig, spoke of Felt leaking material to The New York Times. Nixon said, "he's a bad guy, you see." He said that William Sullivan had told him of Felt's ambition to be Director of the Bureau.[53]

Clashes with Ruckelshaus and resignation[edit]

Felt called his relationship with Ruckelshaus "stormy".[54] In his memoir, Felt describes Ruckelshaus as a "security guard sent to see that the FBI did nothing which would displease Mr. Nixon".[55]

In mid-1973 The New York Times published a series of articles about wiretaps that had been ordered by Hoover during his tenure at the FBI. Ruckelshaus believed that the information must have come from someone at the FBI.

In June 1973 Ruckelshaus received a call from someone claiming to be a New York Times reporter, telling him that Felt was the source of this information.[56] On June 21, Ruckelshaus met privately with Felt and accused him of leaking information to The New York Times, a charge that Felt adamantly denied.[48] Ruckelshaus told Felt to "sleep on it" and let him know the next day what he wanted to do. Felt resigned from the Bureau the next day, June 22, 1973, ending his thirty-one year career.

In a 2013 interview, Ruckelshaus noted the possibility that the original caller was a hoax. He said that he considered Felt's resignation "an admission of guilt" anyway.[56]

Ruckelshaus, who had served only as Acting Director, was replaced several weeks later by Clarence M. Kelley, who had been nominated by Nixon as FBI Director and confirmed by the Senate.

Trial and conviction[edit]

In the early 1970s Felt had supervised Operation COINTELPRO, initiated by Hoover in the 1950s. This period of FBI history has generated great controversy for its abuses of private citizens' rights. The FBI was spying on, infiltrating, and disrupting the Civil Rights Movement, Anti-War Movement, Black Panthers, and other New Left groups. By 1972 Felt was heading the investigation into the Weather Underground, which had planted bombs at the Capitol, the Pentagon, and the State Department building. Felt, along with Edward S. Miller, authorized FBI agents to break into homes secretly in 1972 and 1973, without a search warrant, on nine separate occasions. These kinds of FBI operations were known as "black bag jobs". The break-ins occurred at five addresses in New York and New Jersey, at the homes of relatives and acquaintances of Weather Underground members. They did not contribute to the capture of any fugitives. The use of "black bag jobs" by the FBI was declared unconstitutional by the United States Supreme Court in the Plamondon case, 407 U.S. 297 (1972).

The Church Committee of Congress revealed the FBI's illegal activities, and many agents were investigated. In 1976 Felt publicly stated he had ordered break-ins, and recommended against punishment of individual agents who had carried out orders. Felt also stated that Patrick Gray had also authorized the break-ins, but Gray denied this. Felt said on the CBS television program Face the Nation he would probably be a "scapegoat" for the Bureau's work.[57] "I think this is justified and I'd do it again tomorrow," he said on the program. While admitting the break-ins were "extralegal", he justified them as protecting the "greater good". Felt said:

To not take action against these people and know of a bombing in advance would simply be to stick your fingers in your ears and protect your eardrums when the explosion went off and then start the investigation.

Griffin B. Bell, the Attorney General in the Jimmy Carter administration, directed investigation of these cases. On April 10, 1978, a federal grand jury charged Felt, Miller, and Gray with conspiracy to violate the constitutional rights of American citizens by searching their homes without warrants.

The indictment charged violations of Title 18, Section 241 of the United States Code and stated Felt and the others:

Did unlawfully, willfully, and knowingly combine, conspire, confederate, and agree together and with each other to injure and oppress citizens of the United States who were relatives and acquaintances of the Weatherman fugitives, in the free exercise and enjoyments of certain rights and privileges secured to them by the Constitution and the laws of the United States of America.[58]

Felt told his biographer Ronald Kessler: I was shocked that I was indicted. You would be too, if you did what you thought was in the best interests of the country and someone on technical grounds indicted you.[59]

Felt, Gray, and Miller were arraigned in Washington, DC on April 20. Seven hundred current and former FBI agents were outside the courthouse applauding the "Washington Three", as Felt referred to himself and his colleagues in his memoir.[60] Gray's case did not go to trial and was dropped by the government for lack of evidence on December 11, 1980.[61][62][63]

Felt and Miller attempted to plea bargain with the government, willing to agree to a misdemeanor guilty plea to conducting searches without warrants—a violation of 18 U.S.C. § 2236. The government rejected the offer in 1979. After eight postponements, the case against Felt and Miller went to trial in the United States District Court for the District of Columbia on September 18, 1980.[64] On October 29, former President Richard M. Nixon appeared as a rebuttal witness for the defense.[65][66] He testified that in authorizing the Bureau to conduct break-ins to gather foreign intelligence information "he was acting on precedents established by a number of Presidential directives dating to 1939." It was Nixon's first courtroom appearance since his resignation in 1974. Nixon also contributed money to Felt's defense fund, since Felt's legal expenses were running over $600,000 by then. Also testifying were former Attorneys General Mitchell, Kleindienst, Herbert Brownell Jr., Nicholas Katzenbach, and Ramsey Clark, all of whom said warrantless searches in national security matters were commonplace and understood not to be illegal. Mitchell and Kleindienst denied they had authorized any of the break-ins at issue in the trial. (The Bureau used a national security justification for the searches because it alleged the Weather Underground was in the employ of Cuba.[67])

The jury returned guilty verdicts on November 6, 1980, two days after the presidential election.[68][69][70] The charge carried a maximum sentence of ten years in prison and a $10,000 fine; on December 15, Judge William Bryant fined Felt $5,000 and Miller $3,500, but imposed no jail time for either.[59][71][72] Writing an OpEd piece in The New York Times a week after the conviction, attorney Roy Cohn claimed that Felt and Miller were being used as scapegoats by the Carter administration and it was an unfair prosecution. Cohn wrote the break-ins were the "final dirty trick" of the Nixon administration, and there had been no "personal motive" to their actions.[73] The New York Times praised the convictions, saying "the case has established that zeal is no excuse for violating the Constitution."[74]

Felt and Miller appealed their verdicts.[71][72][75]

Pardon[edit]

In a phone call on January 30, 1981, Edwin Meese encouraged President Ronald Reagan to issue a pardon. After further encouragement from Felt's former colleagues, President Reagan pardoned Felt and Miller. The pardon was signed on March 26, but due to the assassination attempt on March 30, was not announced to the public until April 15, 1981.[76][77][78]

In the pardon, Reagan wrote:

During their long careers, Mark Felt and Edward Miller served the Federal Bureau of Investigation and our nation with great distinction. To punish them further—after 3 years of criminal prosecution proceedings—would not serve the ends of justice. Their convictions in the U.S. District Court, on appeal at the time I signed the pardons, grew out of their good-faith belief that their actions were necessary to preserve the security interests of our country. The record demonstrates that they acted not with criminal intent, but in the belief that they had grants of authority reaching to the highest levels of government.[79]

Nixon sent Felt and Miller bottles of champagne with the note "Justice ultimately prevails."[80] The New York Times disapproved in an editorial, saying that the United States "deserved better than a gratuitous revision of the record by the President".[81] Felt and Miller said they would seek repayment of their legal fees from the government.

The prosecutor at the trial, John W. Nields Jr., said, "I would warrant that whoever is responsible for the pardons did not read the record of the trial and did not know the facts of the case." Nields also complained that the White House did not consult with the prosecutors in the case, which was contrary to the usual practice when a pardon was under consideration.[75]

Felt said,

I feel very excited and just so pleased that I can hardly contain myself. I am most grateful to the President. I don't know how I'm ever going to be able to thank him. It's just like having a heavy burden lifted off your back. This case has been dragging on for five years.

At a press conference the day of the announcement, Miller said, "I certainly owe the Gipper one."[77][82] Carter Attorney General Griffin Bell said he did not object to the pardons, as the convictions had upheld constitutional principles.

Despite their pardons, Felt and Miller won permission from the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit to appeal their convictions so as to remove it from their record and to prevent it from being used in civil suits by victims of the break-ins they had ordered.[83] Ultimately, the court restored Felt's law license in 1982, based on Reagan's pardon. In June 1982, Felt and Miller testified before the Senate Judiciary Committee's security and terrorism subcommittee. They said that the restrictions placed on the FBI by Attorney General Edward H. Levi were threatening the country's safety.[84]

Family life[edit]

His daughter Joan graduated from high school in Kansas City during his assignment there and attended the University of Kansas for two years before transferring to Stanford in California to study drama.[85] When she was an undergraduate, Felt finally settled in Alexandria, Virginia, when he took his post at the FBI Academy.[86]

Prior to the Watergate scandal, Felt had become estranged from Joan. They had been close during her childhood, but after she graduated from Stanford, she had gone to Chile under a Fulbright scholarship to continue her studies. While there, she became friends with Marxist revolutionary Andrés Pascal Allende, nephew of future president Salvador Allende. When she returned home, her political views had shifted to the extreme left, putting her in conflict with her conservative father.[85]

She earned her master's degree in Spanish at Stanford,[86] and then joined a hippie community in the Santa Cruz Mountains. Felt and his wife went to visit her once and were appalled at her counterculture lifestyle and use of drugs; he was reminded of members of the militant Weather Underground that the FBI had been prosecuting. Joan's friends were equally shocked that her father was an FBI agent. Following their visit, Joan cut off most contact with her parents. As a result, and combined with the fact that she did not follow the news, she was unaware of her father's legal problems that arose from the Watergate scandal.[85]

Over the years, the stress of following her husband's career as well as from the separation from her daughter, combined with Felt's prosecution had taken their toll on Audrey. During Felt's time in Seattle in 1954, Audrey suffered a nervous breakdown. She developed a dependency on alcohol and had been taking antidepressants for years. She had also been hospitalized several times for various ailments. When Felt was put on trial in 1980, she attended the first day, but did not return because she was unable to bear it. In 1984 she committed suicide using Felt's revolver.[85] Felt and his son Mark Jr., an officer in the United States Air Force, decided to keep this a secret and told Joan that her mother had died of a heart attack.[87] Joan did not learn the truth about her mother until 2001.[85]

Meanwhile, Joan had become an adherent of Adi Da, who had founded a new religious movement in San Francisco called Adidam, and she was living in Santa Rosa. She had borne three sons – Ludi (later Will), Rob, and Nick, the latter two from another Adidam devotee whom she never married – but her parents had only met Ludi during their visit in 1974. After Audrey's death, Felt began making yearly visits to see Joan and his grandsons, and they also came to visit him and his new girlfriend, who lived in the same apartment complex.[85]

In 1990 Felt permanently moved to Santa Rosa, leaving behind his entire life in Alexandria. He bought a house where he lived with Joan, and took care of the boys while she worked, teaching at Sonoma State University and Santa Rosa Junior College.[85] He suffered a stroke before 1999, as reported by Kessler in his book The Bureau. According to Kessler's book, in the summer of 1999, Woodward showed up unexpectedly at the Santa Rosa home and took Felt to lunch.[88]

Joan, who was caring for her father, told Kessler that her father had greeted Woodward like an old friend. Their meeting appeared to be more of a celebration than an interview. "Woodward just showed up at the door and said he was in the area," Joan Felt was quoted as saying in Kessler's book, which was published in 2002. "He came in a white limousine, which parked at a schoolyard about ten blocks away. He walked to the house. He asked if it was okay to have a martini with my father at lunch, and I said it would be fine."[88]

Memoir[edit]

Felt published his memoir The FBI Pyramid: From the Inside in 1979. It was co-written with Hoover biographer Ralph de Toledano, though the latter's name appears only in the copyright notice. Toledano in 2005 wrote that the volume was "largely written by me since his original manuscript read like The Autocrat of the Breakfast-Table". Toledano said: Felt swore to me that he was not Deep Throat, and that he had never leaked information to the Woodward-Bernstein team or anyone else. The book was published and bombed.[89]

In his memoir, Felt strongly defended Hoover and his tenure as Director; he condemned the criticisms of the Bureau made in the 1970s by the Church Committee and civil libertarians. He also denounced the treatment of Bureau agents as criminals and said the Freedom of Information Act and Privacy Act of 1974 served only to interfere with government work and helped criminals. (He opens the book with the sentence, "The Bill of Rights is not a suicide pact", Justice Robert H. Jackson's comment in his dissent to Terminiello v. City of Chicago, 337 U.S. 1 (1949)).[5]

Library Journal wrote in its review that "at one time Felt was assumed to be Watergate's 'Deep Throat'; in this interesting but hardly sensational memoir, he makes it clear that that honor, if honor it be, lies elsewhere."[90] The New York Times Book Review was highly critical of the book, saying Felt "seeks to perpetuate a view of Hoover and the FBI that is no longer seriously peddled even on the backs of cereal boxes". It said the book contained "a disturbing number of factual errors".[91] Curt Gentry said that Felt was "the keeper of the Hoover flame".[92]

Kessler said in his book that the measures Woodward took to conceal his meeting with Felt lent "credence" to the notion that Felt was Deep Throat. Woodward confirmed that Felt was Deep Throat in 2005. "There are plenty of people claiming they knew Deep Throat was actually former FBI man Mark Felt ... On May 3, 2002, PAGE SIX reported that Ronald Kessler, author of The Bureau: The Secret History of the FBI, says that all the evidence points to former top FBI official W. Mark Felt."[93]

Deep Throat speculation[edit]

The identity of Deep Throat was debated for more than three decades, and Felt was frequently mentioned as a possibility. An October 1990 Washingtonian magazine article about "Washington secrets" listed the 15 most prominent Deep Throat candidates, including Felt.

Jack Limpert published evidence as early as 1974 that Felt was the informant.[94] On June 25 of that year, a few weeks after All the President's Men was published, The Wall Street Journal ran an editorial, "If You Drink Scotch, Smoke, Read, Maybe You're Deep Throat." It began "W. Mark Felt says he isn't now, nor has he ever been Deep Throat." The Journal quoted Felt saying the character was a "composite" and "I'm just not that kind of person."[95] In 1975 George V. Higgins wrote: "Mark Felt knows more reporters than most reporters do, and there are some who think he had a Washington Post alias borrowed from a dirty movie."[96] During a grand jury investigation in 1976, Felt was called to testify. The prosecutor, J. Stanley Pottinger, Assistant Attorney General for Civil Rights, discovered that Felt was "Deep Throat", but the secrecy of the proceedings protected the information from being public.[97]

In 1992 James Mann, who had been a reporter at The Washington Post in 1972 and worked with Woodward, wrote a piece for The Atlantic Monthly, saying the source had to have been within the FBI. He noted Felt as a possibility, but said he could not confirm this.[98]

Alexander P. Butterfield, the White House aide best known for revealing Nixon's taping system, told the Hartford Courant in 1995, "I think it was a guy named Mark Felt."[99] In July 1999, Felt was identified as Deep Throat by the Hartford Courant, citing Chase Culeman-Beckman, a nineteen-year-old from Port Chester, New York. Culeman-Beckman said Jacob Bernstein, the son of Carl Bernstein and Nora Ephron, had told him the name at summer camp in 1988, and that Jacob claimed he had been told by his father. Felt said to the Courant, "No, it's not me. I would have done better. I would have been more effective. Deep Throat didn't exactly bring the White House crashing down, did he?" Bernstein said his son didn't know. "Bob and I have been wise enough never to tell our wives, and we've certainly never told our children."[100] (Bernstein reiterated on June 2, 2005, on the Today Show that his wife had never known.)

Leonard Garment, President Nixon's former law partner who became White House counsel after John W. Dean's resignation, ruled Felt out as Deep Throat in his 2000 book In Search of Deep Throat. Garment wrote:

The Felt theory was a strong one ... Felt had a personal motive for acting. After the death of J. Edgar Hoover ... Felt thought he was a leading candidate to succeed Hoover ... The characteristics were a good fit. The trouble with Felt's candidacy was that Deep Throat in All the President's Men simply did not sound to me like a career FBI man.[101]

Garment said the information leaked to Woodward was inside White House information to which Felt would not have had access. "Felt did not fit."[102] (Once the secret was revealed, it was noted Felt did have access to such information because the Bureau's agents were interviewing high-ranking White House officials.)

In 2002 the San Francisco Chronicle profiled Felt. Noting his denial in The FBI Pyramid, the paper wrote:

Curiously, his son—American Airlines pilot Mark Felt—now says that shouldn't be read as a definitive denial, and that he plans to answer the question once-and-for-all in a second memoir. The excerpt of the working draft obtained by the Chronicle has Felt still denying he's Throat but providing a rationale for why Throat did the right thing.[103]

In February 2005 reports surfaced that Woodward had prepared Deep Throat's obituary because he was near death. Chief Justice William Rehnquist was battling cancer at the time (he would die in September 2005), and there was speculation that Rehnquist might have been Deep Throat. Rehnquist was Assistant Attorney General of the Office of Legal Counsel, from 1969 to 1971,[104] and then served on the Supreme Court until his death in 2005.

Deep Throat revealed[edit]

Vanity Fair magazine revealed that Felt was Deep Throat on May 31, 2005, when it published an article (eventually appearing in the July issue of the magazine) on its website by John D. O'Connor, an attorney acting on Felt's behalf. Felt said, "I'm the guy they used to call Deep Throat." After the Vanity Fair story broke, Benjamin C. Bradlee, the editor of the Washington Post during Watergate, confirmed that Felt was Deep Throat. According to the Vanity Fair article, Felt was persuaded to come out by his family. They hoped to capitalize on the book deals and other lucrative opportunities which Felt would be offered in order to help pay for his grandchildren's education.[2] His family was unaware that he was Deep Throat for many years. They realized the truth after his retirement, when they became aware of his close friendship with Bob Woodward.

Nixon's Chief Counsel Charles Colson, who served prison time for his actions in the Nixon White House, said Felt had violated "his oath to keep this nation's secrets".[105] A Los Angeles Times editorial argued that this argument was specious, "as if there's no difference between nuclear strategy and rounding up hush money to silence your hired burglars".[106] Ralph de Toledano, who co-wrote Felt's 1979 memoir, said Mark Felt Jr. had approached him in 2004 to buy Toledano's half of the copyright. Toledano agreed to sell but was never paid. He attempted to rescind the deal, threatening legal action. A few days before the Vanity Fair article was released, Toledano finally received a check.

He later said: "I had been gloriously and illegally deceived, and Deep Throat was, in characteristic style, back in business—which given his history of betrayal, was par for the course."[89]

After the revelation, publishers were interested in signing Felt to a book deal. Weeks later, PublicAffairs Books announced that it signed a deal with Felt. Its CEO was a Washington Post reporter and editor during the Watergate era. The new book was to include material from Felt's 1979 memoir, plus an update. The new volume was scheduled for publication in early 2006. Felt sold the movie rights to his story to Universal Pictures for development by Tom Hanks's production company, Playtone. The book and movie deals were valued at US $1 million.[107] A film based on those rights, Mark Felt: The Man Who Brought Down the White House, in which Felt is portrayed by Liam Neeson, was released in 2017.

In mid-2005 Woodward published an account of his contacts with Felt, The Secret Man: The Story of Watergate's Deep Throat (ISBN 0-7432-8715-0).

Appraisal of Watergate role[edit]

Public response to Felt and his actions has varied widely since these revelations. In the immediate aftermath, Felt's family called him an "American hero", suggesting that he leaked information for moral or patriotic reasons. G. Gordon Liddy, who was convicted of burglary in the Watergate scandal, said Felt should have gone to the grand jury rather than leak.[108]

Speculation about Felt's motives for leaking has also varied widely. Some suggested that it was revenge for Nixon's choosing Gray over Felt to replace Hoover as FBI Director. Others suggest Felt acted out of institutional loyalty to the FBI.

Political scientist George Friedman argued:

The Washington Post created a morality play about an out-of-control government brought to heel by two young, enterprising journalists and a courageous newspaper. That simply wasn't what happened. Instead, it was about the FBI using The Washington Post to leak information to destroy the president, and The Washington Post willingly serving as the conduit for that information while withholding an essential dimension of the story by concealing Deep Throat's identity.[109]

In his 2012 book Leak: Why Mark Felt Became Deep Throat, Max Holland argued that Felt leaked the information in an attempt to become head of the FBI. Holland said that Felt wanted to create the perception that Gray "could not control the FBI". This could result in Nixon's firing Gray, leaving Felt as the obvious choice to run the agency. Holland said this plan (if it was one) backfired as Nixon and his team found out that Felt was the leaker.[110]

Death[edit]

Felt died at home, in his sleep, on December 18, 2008.[111] He was 95 years old and his death was attributed to heart failure.[112]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ Robert Yoon and Stephen Bach (June 3, 2005). "Tapes: Nixon suspected Felt". CNN.com.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- ^ a b "I'm the Guy They Called Deep Throat". Vanity Fair. July 2005. Retrieved May 28, 2013.

- ^ "40 years later, remembering Watergate scandal's 'Deep Throat'". CNN. June 15, 2012.

- ^ W. Mark Felt, The FBI Pyramid: From the Inside (New York: Putnam, 1979) p. 11; & Ronald Kessler, The F.B.I.: Inside the World's Most Powerful Law Enforcement Agency (New York: Pocket Books, 1994), p. 163.

- ^ a b Felt, FBI Pyramid, p. 11.

- ^ a b "Ancestry of Mark Felt". www.wargs.com.

- ^ a b "Seniors". Gem of the Mountains, University of Idaho yearbook. 1935. p. 41.

- ^ "Beta Theta Pi". Gem of the Mountains, University of Idaho yearbook. 1935. p. 263.

- ^ Yenser, Pamela; Yenser, Kelly (Fall 2005). "Mark Felt's deep secret". Here We Have Idaho. University of Idaho. (Alumni magazine). p. 8.

- ^ "Seniors". Gem of the Mountains, University of Idaho yearbook. 1937. p. 200.

- ^ Felt, FBI Pyramid, p. 18.

- ^ Felt, FBI Pyramid, p. 18; & Anthony Theoharis, Tony G. Poveda, Susan Rosenfeld, and Richard Powers eds., The FBI: A Comprehensive Reference Guide (New York: Checkmark Books, 2000), pp. 324–325.

- ^ Theoharis et al., FBI: Reference Guide, pp. 324–325.

- ^ Felt, FBI Pyramid, p. 19.

- ^ W. Mark Felt, The FBI Pyramid: From the Inside (New York: Putnam, 1979) p. 25.

- ^ Thaddeus Holt. The Deceivers: Allied Military Deception in the Second World War. New York: Scribner, 2004. 452–456

- ^ Felt, p. 29ff.

- ^ a b c Felt, p. 45.

- ^ Wadsworth, Nelson (January 22, 1958). "Firing from th' hip easy for FBI agents". Deseret News. (Salt Lake City, Utah). p. B9.

- ^ J. Edgar Hoover: The Man And The Secrets, by Curt Gentry, 1991.

- ^ John O'Connor, "'I'm the Guy They Called Deep Throat'", Vanity Fair PDF

- ^ Felt, FBI Pyramid, p. 59.

- ^ Felt, FBI Pyramid, p. 67.

- ^ Theoharis et al., FBI: Reference Guide, p. 315, p. 470; & Curt Gentry, J. Edgar Hoover: The Man and the Secrets (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1991), p. 624.

- ^ Powers, Richard Gid (2004). Broken: The Troubled Past and Uncertain Future of the FBI. Simon and Schuster. p. 289. ISBN 9780684833712.

- ^ Felt, FBI Pyramid, page number not given

- ^ Kessler, F.B.I.: Inside the Agency, p. 163.

- ^ Gentry, J. Edgar Hoover: The Man and the Secrets, p. 24.

- ^ William C. Ibershof (October 9, 2008). "Letter to the Editor: Prosecuting Weathermen". The New York Times.

- ^ Gentry, J. Edgar Hoover: The Man and the Secrets, p. 43.

- ^ Gentry, J. Edgar Hoover: The Man and the Secrets, p. 49.

- ^ a b Gentry, J. Edgar Hoover: The Man and the Secrets, p. 50; & United States Congress, House of Representatives, "Inquiry Into the Destruction of Former FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover's Files and FBI Recordkeeping: Hearing Before a Subcommittee of the Committee on Government Operations."

- ^ a b United States Congress, House of Representatives, "Inquiry Into the Destruction of Former FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover's Files and FBI Recordkeeping: Hearing Before a Subcommittee of the Committee on Government Operations."

- ^ Felt, FBI Pyramid, p. 216.

- ^ a b c d Felt, FBI Pyramid, p. 225.

- ^ Woodward, The Secret Man: The Story of Watergate's Deep Throat, p. 51

- ^ a b Felt, FBI Pyramid, p. 186.

- ^ Felt, FBI Pyramid, p. 245.

- ^ Kessler, F.B.I.: Inside the Agency, p. 269.

- ^ Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein, All the President's Men, 2nd ed. (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1994), p. 71.

- ^ Woodward and Bernstein, All the President's Men, p. 131.

- ^ Bob Woodward, "How Mark Felt Became 'Deep Throat'", The Washington Post; Woodward Secret Man, p. 16

- ^ Brokaw, Tom (July 6, 2005). "The Story behind 'Deep Throat'". NBC News.

- ^ Bernstein and Woodward, All the President's Men, p. 71.

- ^ Adrian Havill, Deep Truth: The Lives of Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein (New York: Carol Publishing, 1993), pp. 78–82.

- ^ "Voice from the shadows", The Sydney Morning Herald, p. 35.

- ^ Stanley Kutler, Abuse of Power: The New Nixon Tapes (New York: Touchstone, 1998), p. 67.

- ^ a b Dobbs, Michael (June 20, 2005). "Watergate and the Two Lives of Mark Felt: Roles as FBI Official, 'Deep Throat' Clashed". Washington Post. p. A01. Retrieved July 25, 2007.

- ^ Felt, FBI Pyramid, p. 227.

- ^ Felt, FBI Pyramid, p. 278.

- ^ Felt, FBI Pyramid, p. 293; Kessler, F.B.I.: Inside the Agency, p. 181; & Kutler, Abuse of Power, p. 347.

- ^ Kutler, Abuse of Power, p. 347.

- ^ Kutler, Abuse of Power, p. 454.

- ^ Felt, FBI Pyramid, p. 300.

- ^ Felt, FBI Pyramid, p. 293.

- ^ a b Mark F., Bernstein (October 9, 2013). "Q&A: William Ruckelshaus '55 on the Watergate Scandal". Princeton Alumni Weekly.

- ^ John Crewdson (August 30, 1976), "Ex-F.B.I. Aide Sees 'Scapegoat' Role", The New York Times, p. 21.

- ^ Felt, FBI Pyramid, p. 333.

- ^ a b Kessler, F.B.I.: Inside the Agency, p. 194.

- ^ Felt, FBI Pyramid, p. 337.

- ^ "Ex-FBI chief cleared on break-in charges". Eugene Register-Guard. (Oregon). UPI. December 11, 1980. p. 3A.

- ^ "Judge drops Gray counts". The Bulletin. (Bend, Oregon). UPI. December 11, 1980. p. 1.

- ^ "Justice drops charges against Gray". Wilmington Morning Star. (North Carolina). (New York Times). December 12, 1980. p. 3A.

- ^ Robert Pear: "Conspiracy Trial for 2 Ex-F.B.I. Officials Accused in Break-ins", The New York Times, September 19, 1980; & "Long Delayed Trial Over F.B.I. Break-ins to Start in Capital Tomorrow", The New York Times, September 14, 1980, p. 30.

- ^ "Nixon testifies for ex-FBI officials". Spokesman-Review. (Spokane, Washington). Associated Press. October 30, 1980. p. 5.

- ^ "Nixon defends break-ins". The Bulletin. (Bend, Oregon). UPI. October 30, 1980. p. 1.

- ^ Robert Pear, "Testimony by Nixon Heard in F.B.I. Trial", The New York Times, October 30, 1980.

- ^ "Jury convicts 2 ex-FBI officials". Spokesman-Review. (Spokane, Washington). (New York Times). November 7, 1980. p. 3.

- ^ "2 former FBI officials found guilty in 1970s home break=in cases". Toledo Blade. (Ohio). Associated Press. November 7, 1980. p. 1.

- ^ "Ex-FBI chiefs found guilty". The Bulletin. (Bend, Oregon). UPI. November 6, 1980. p. 1.

- ^ a b "Ex-FBI officials draw fines, no jail terms". The Bulletin. (Bend, Oregon). UPI. December 15, 1980. p. 1.

- ^ a b "Ex-FBI pair facing fines but not jail". Spokesman-Review. (Spokane, Washington). Associated Press. December 16, 1980. p. 3.

- ^ Roy Cohn, "Stabbing the F.B.I.", The New York Times, November 15, 1980, p. 20.

- ^ "The Right Punishment for F.B.I. Crimes." (Editorial), The New York Times, December 18, 1980.

- ^ a b Robert Pear, "President Pardons 2 Ex-F.B.I. Officials in 1970's Break-ins", The New York Times; & Lou Cannon and Laura A. Kiernan, "President Pardons 2 Ex-FBI Officials Guilty in Break-Ins", The Washington Post.

- ^ Pear, Robert (April 16, 1981). "Ex-FBI officials granted pardons". Spokesman-Review. (Spokane, Washington). (New York Times). p. 3.

- ^ a b "Former FBI officials, convicted in break-ins, are pardoned by Reagan". Toledo Blade. (Ohio). Associated Press. April 16, 1981. p. 1.

- ^ "Reagan thought jury erred on FBI". The Bulletin. (Bend, Oregon). UPI. April 16, 1981. p. 1.

- ^ Statement on Granting Pardons to W. Mark Felt and Edward S. Miller, Ronald Reagan. April 15, 1981.

- ^ Gentry, J. Edgar Hoover: The Man and the Secrets, p. 595; Robert Sam Anson, Exile: The Unquiet Oblivion of Richard M. Nixon, p. 233; Laurie Johnston and Robert McG. Thomas, "Congratulations and Champagne from Nixon."

- ^ "Pardoning the F.B.I's Past." (Editorial), The New York Times, April 16, 1980.

- ^ "Watergate Ghosts Rise Again". Time. Vol. 117 no. 2. 1981. p. 62.

- ^ Joe Pichirallo, "Judge Allows Appeals by Ex-Officials Of FBI Despite Pardons by Reagan", The Washington Post.

- ^ Felt, FBI Pyramid, p. 349.

- ^ a b c d e f g Ryan, Joan (May 28, 2006). "Family Man". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved May 28, 2018.

- ^ a b Duke, Lynne (June 12, 2005). "Deep Throat's Daughter, The Kindred Free Spirit". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved May 28, 2018.

- ^ Duke, Lynne (April 22, 2006). "Deep Throat's Other Secret". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved May 28, 2018.

- ^ a b Kessler, Ronald (2016). The Bureau: The Secret History of the FBI. St. Martin's Press. p. 201. ISBN 9781250111265.

- ^ a b Ralph de Toledano, "Deep Throat's Ghost." The American Conservative. July 4, 2005.

- ^ Henry Steck, "Review of The FBI Pyramid", Library Journal.

- ^ David Wise, "Apologia by No. 2", The New York Times Book Review.

- ^ Gentry, J. Edgar Hoover: The Man and the Secrets, p. 728.

- ^ New York Post, June 3, 2005

- ^ Jack Limpert, "Deeper Into Deep Throat", Washingtonian.

- ^ Woodward, Secret Man, p. 116.

- ^ George V. Higgins (1975), The Friends of Richard Nixon, 1976 reprint, New York: Ballantine, Ch. 14, p. 147, ISBN 978-0-345-25226-5.

- ^ Woodward, Secret Man, p. 131.

- ^ James Mann, "Deep Throat: An Institutional Analysis", The Atlantic Monthly.

- ^ Frank Rizzo, "Nixon one role will remain nameless", The Hartford Courant.

- ^ David Daley, "Deep Throat: 2 boys talking politics at summer camp may have revealed a Watergate secret", The Hartford Courant.

- ^ Leonard Garment, In Search of Deep Throat: The Greatest Political Mystery of Our Time, pp. 146–47.

- ^ Leonard Garment, In Search of Deep Throat: The Greatest Political Mystery of Our Time, pp. 170–71.

- ^ Vicki Haddock, "The Bay Area's 'Deep Throat' candidate", San Francisco Chronicle.

- ^ "LII: US Supreme Court: Justice Rehnquist". Supct.law.cornell.edu. Retrieved September 19, 2008.

- ^ Tom Raum. "Turncoat or U.S. hero? Deep Throat casts divide." Journal–Gazette (Ft. Wayne, Indiana). June 2, 2005. 1A.

- ^ "Deep Thoughts" (editorial). Los Angeles Times. June 2, 2005. B10.

- ^ Bob Thompson. "Deep Throat Family Cuts Publishing, Film Pacts; Tom Hanks to Develop Movie About Secret Watergate Source" The Washington Post. June 16, 2005. C1.

- ^ Martin Schram. "Nixon's henchmen lecture us on ethics" Newsday. June 6, 2005. A32.

- ^ "The deeper truth about Deep Throat". MercatorNet. December 24, 2008. Retrieved April 9, 2010.

- ^ Shafer, Jack (February 21, 2012). "What made Deep Throat leak?". Reuters Blogs.

- ^ Sullivan, Patricia (December 20, 2008). "Lawman's Unwavering Compass Led Him to White House Showdown". Washington Post. Retrieved April 12, 2016.

- ^ Neuman, Johanna (December 19, 2016). "W. Mark Felt, Watergate source 'Deep Throat,' dies at 95". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on June 17, 2015. Retrieved April 12, 2016.

Bibliography[edit]

- Anson, Robert Sam. Exile: The Unquiet Oblivion of Richard M. Nixon. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1984. (ISBN 0-671-44021-7)

- Benfell, Carol. "A Family Secret: Joan Felt Explains Why Family Members Urged Her Father, Watergate's 'Deep Throat' to Reveal His Identity". The Press Democrat (Santa Rosa, California). June 5, 2005. A1.

- Bernstein, Carl and Bob Woodward. All the President's Men. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1974. (ISBN 0-671-21781-X)

- Cannon, Lou and Laura A. Kiernan. "President Pardons 2 Ex-FBI Officials Guilty in Break-Ins". The Washington Post. April 16, 1981. A1.

- Cohn, Roy. "Stabbing the F.B.I." The New York Times. November 15, 1980. 20.

- Crewdson, John. "Ex-Aide Approved F.B.I. Burglaries." The New York Times. August 18, 1976. A1.

- Crewdson, John. "Ex-F.B.I. Aide Sees 'Scapegoat' Role". The New York Times. August 30, 1976. 21.

- Daley, David. "Deep Throat: 2 boys talking politics at summer camp may have revealed a Watergate secret." The Hartford Courant. July 28, 1999. A1.

- "Deep Thoughts" (editorial). Los Angeles Times. June 2, 2005. B10.

- Duke, Lynne. "Deep Throat's Daughter, The Kindred Free Spirit" The Washington Post. June 12, 2005. A1.

- Felt, W. Mark. The FBI Pyramid: From the Inside. New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons, 1979. (ISBN 0-399-11904-3).

- Garment, Leonard. In Search of Deep Throat: The Greatest Political Mystery of Our Time. New York: Basic Books, 2000. ISBN 0-465-02613-3

- Gentry, Curt. J. Edgar Hoover: The Man and the Secrets. New York: W.W. Norton, 1991. (ISBN 0-393-02404-0)

- Haddock, Vicki. "The Bay Area's 'Deep Throat' candidate." The San Francisco Chronicle. June 16, 2002. D1.

- Havill, Adrian. Deep Truth: The Lives of Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein. New York: Birch Lane Press, 1993. ISBN 1-55972-172-3

- Higgins, George V. The Friends of Richard Nixon. New York: Ballantine, 1976 reprint [1975]. ISBN 978-0-345-25226-5

- Holland, Max. Leak: Why Mark Felt Became Deep Throat. Lawrence, Kansas, University Press of Kansas, 2012. ISBN 978-0-7006-1829-3

- Holt, Thaddeus, "The Deceivers: Allied Military Deception in the Second World War". New York: Scribner, 2004. ISBN 0-7432-5042-7.

- Horrock, Nicholas M. "Gray and 2 Ex-F.B.I Aides Indicted on Conspiracy in Search for Radicals." The New York Times. April 11, 1978. A1.

- Johnston, David, "Behind Deep Throat's Clandestine Ways, a Cloak-and-Dagger Past." The New York Times. June 4, 2005

- Johnston, Laurie and Robert McG. Thomas. "Congratulations and Champagne from Nixon." The New York Times. April 30, 1981. C18.

- Kamen, Al and Laura A. Kiernan. "Lawyers". The Washington Post. June 28, 1982. B3.

- Kessler, Ronald. The F.B.I.: Inside the World's Most Powerful Law Enforcement Agency. New York: Pocket Books, 1993. ISBN 0-671-78657-1

- Kutler, Stanley I., editor. Abuse of Power: The New Nixon Tapes. New York: The Free Press, 1997. ISBN 0-684-84127-4

- Lardner, George. "Attorney General Backs FBI Pardons but Ex-Prosecutor Disagrees". The Washington Post. April 17, 1981. A9.

- Limpert, Jack. "Deeper Into Deep Throat". Washingtonian. August 1974.

- Mann, James. "Deep Throat: An Institutional Analysis". The Atlantic Monthly. May 1992.

- Marro, Anthony. "Gray and 2 Ex-F.B.I. Aides Deny Guilt as 700 at Court Applaud Them". The New York Times. April 21, 1978. A13.

- O'Connor, John D. "'I'm the Guy They Called Deep Throat'". Vanity Fair. July 2005. 86–89, 129–133. Retrieved on November 21, 2008.

- "Pardoning the F.B.I's Past". (Editorial). The New York Times. April 16, 1980. A30.

- Pear, Robert. "Conspiracy Trial for 2 Ex-F.B.I. Officials Accused in Break-ins." The New York Times. September 19, 1980. A14.

- Pear, Robert. "Long Delayed Trial Over F.B.I. Break-ins to Start in Capital Tomorrow". The New York Times. September 14, 1980. 30.

- Pear, Robert. "President Pardons 2 Ex-F.B.I. Officials in 1970's Break-ins." The New York Times. April 16, 1981. A1.

- Pear, Robert. "Prosecutors Rejected Offer of Plea to F.B.I. Break-ins". The New York Times. January 11, 1981. 24.

- Pear, Robert. "Testimony by Nixon Heard in F.B.I. Trial." The New York Times. October 30, 1980. A17.

- Pear, Robert. "2 Ex-F.B.I. Agents Get Light Fines for Authorizing Break-ins in 70's". The New York Times. December 16, 1980. A1.

- Pear, Robert. "2 Pardoned Ex-F.B.I. Officials to Seek U.S. Payment of Some Legal Fees." The New York Times. May 1, 1981. A14.

- Pichirallo, Joe. "Judge Allows Appeals by Ex-Officials Of FBI Despite Pardons by Reagan". The Washington Post. July 24, 1981. C5.

- Raum, Tom. "Turncoat or U.S. hero? Deep Throat casts divide". The Journal–Gazette (Ft. Wayne, Indiana). June 2, 2005. 1A.

- "The Right Punishment for F.B.I. Crimes." (Editorial). The New York Times. December 18, 1980. A30.

- Rizzo, Frank. "Nixon one role will remain nameless." The Hartford Courant. December 17, 1995. G1.

- Schram, Martin. "Nixon's henchmen lecture us on ethics". Newsday. June 6, 2005. A32.

- Steck, Henry. Review of The FBI Pyramid. Library Journal. April 1, 1980. 850.

- Summers, Anthony. Official and Confidential: The Secret Life of J. Edgar Hoover. New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons, 1993. (ISBN 0-399-13800-5)

- Theoharis, Athan G., Tony G. Poveda, Susan Rosefeld, and Richard Gid Powers. The FBI: A Comprehensive Reference Guide. New York: Checkmark Books, 2000. (ISBN 0-8160-4228-4)

- Thompson, Bob. "Deep Throat Family Cuts Publishing, Film Pacts; Tom Hanks to Develop Movie About Secret Watergate Source" The Washington Post. June 16, 2005. C1.

- Toledano, Ralph de. "Deep Throat's Ghost". The American Conservative. July 4, 2005.

- United Press International. "2 Ex-FBI Aides Urge Relation of Spying Rules." The Miami Herald. June 27, 1982. 24A.

- United States Congress. House of Representatives. Committee on Government Operations. Subcommittee on Government Information and Individual Rights. Inquiry Into the Destruction of Former FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover's Files and FBI Recordkeeping: Hearing Before a Subcommittee of the Committee on Government Operations, House of Representatives, 94th Congress, December 1, 1975. Washington, D.C.: United States Government Printing Office, 1975.

- United States. National Archives and Records Administration. Office of the Federal Register. Public Papers of the President: Ronald Reagan, 1981. Washington, D.C.: United States Government Printing Office, 1982. Ronald Reagan Presidential Library, National Archives and Records Administration

- Wise, David. "Apologia by No. 2". The New York Times Book Review. January 27, 1980. 12.

- Woodward, Bob. "How Mark Felt Became 'Deep Throat.'" The Washington Post. June 2, 2005. A1.

- Woodward, Bob. The Secret Man: The Story of Watergate's Deep Throat. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2005. (ISBN 0-7432-8715-0)

External links[edit]

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Mark Felt |

- Dohrn, Jennifer. "I Was The Target Of Illegal FBI Break-Ins Ordered by Mark Felt aka 'Deep Throat'" (June 2, 2005). Democracy Now!

- Dean, John W. Why The Revelation of the Identity Of Deep Throat Has Only Created Another Mystery (June 3, 2005). Findlaw (also see the extensive appendix, containing all of Woodward's references to "Deep Throat" in All The President's Men)

- AP Obituary in the San Francisco Chronicle

- Appearances on C-SPAN

- Mark Felt at Find a Grave

- 1913 births

- 2008 deaths

- American whistleblowers

- Deputy Directors of the Federal Bureau of Investigation

- George Washington University Law School alumni

- Idaho lawyers

- People convicted of depriving others of their civil rights

- People from Santa Rosa, California

- People from Twin Falls, Idaho

- Recipients of American presidential pardons

- Stroke survivors

- University of Idaho alumni

- Watergate scandal investigators

- Writers from Idaho