Parable of the Good Samaritan

The parable of the Good Samaritan is a parable told by Jesus in the Gospel of Luke.[1] It is about a traveller who is stripped of clothing, beaten, and left half dead alongside the road. First a priest and then a Levite comes by, but both avoid the man. Finally, a Samaritan happens upon the traveller. Samaritans and Jews despised each other, but the Samaritan helps the injured man. Jesus is described as telling the parable in response to the question from a lawyer, "And who is my neighbour?". In response, Jesus tells the parable, the conclusion of which is that the neighbour figure in the parable is the man who shows mercy to the injured man—that is, the Samaritan.[2]

Some Christians, such as Augustine, have interpreted the parable allegorically, with the Samaritan representing Jesus Christ, who saves the sinful soul.[3] Others, however, discount this allegory as unrelated to the parable's original meaning[3] and see the parable as exemplifying the ethics of Jesus.[4]

The parable has inspired painting, sculpture, satire, poetry, photography, and film. The phrase "good Samaritan", meaning someone who helps a stranger, derives from this parable, and many hospitals and charitable organizations are named after the Good Samaritan.

Narrative[edit]

In the Gospel of Luke chapter 10, the parable is introduced by a question, known as the Great Commandment:

Behold, a certain lawyer stood up and tested him, saying, "Teacher, what shall I do to inherit eternal life?"

He said to him, "What is written in the law? How do you read it?"

He answered, “You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, with all your soul, with all your strength, and with all your mind; and your neighbour as yourself."

He said to him, "You have answered correctly. Do this, and you will live."

But he, desiring to justify himself, asked Jesus, "Who is my neighbor?"

— Luke 10:25–29, World English Bible

Jesus replies with a story:

Jesus answered, "A certain man was going down from Jerusalem to Jericho, and he fell among robbers, who both stripped him and beat him, and departed, leaving him half dead. By chance a certain priest was going down that way. When he saw him, he passed by on the other side. In the same way a Levite also, when he came to the place, and saw him, passed by on the other side. But a certain Samaritan, as he travelled, came where he was. When he saw him, he was moved with compassion, came to him, and bound up his wounds, pouring on oil and wine. He set him on his own animal, and brought him to an inn, and took care of him. On the next day, when he departed, he took out two denarii, gave them to the host, and said to him, 'Take care of him. Whatever you spend beyond that, I will repay you when I return.' Now which of these three do you think seemed to be a neighbor to him who fell among the robbers?"

He said, "He who showed mercy on him."

Then Jesus said to him, "Go and do likewise."

— Luke 10:30–37, World English Bible

Historical context[edit]

Road from Jerusalem to Jericho[edit]

In the time of Jesus, the road from Jerusalem to Jericho was notorious for its danger and difficulty, and was known as the "Way of Blood" because "of the blood which is often shed there by robbers".[5] Martin Luther King, Jr., in his "I've Been to the Mountaintop" speech, on the day before his death, described the road as follows:

I remember when Mrs. King and I were first in Jerusalem. We rented a car and drove from Jerusalem down to Jericho. And as soon as we got on that road, I said to my wife, "I can see why Jesus used this as the setting for his parable." It's a winding, meandering road. It's really conducive for ambushing. You start out in Jerusalem, which is about 1200 miles—or rather 1200 feet above sea level. And by the time you get down to Jericho, fifteen or twenty minutes later, you're about 2200 feet below sea level. That's a dangerous road.[6]

Samaritans and Jesus[edit]

Jesus' target audience, the Jews, hated Samaritans[7] to such a degree that they destroyed the Samaritans' temple on Mount Gerizim.[8] Due to this hatred, some think that the Lawyer's phrase "The one who had mercy on him" (Luke 10:37) may indicate a reluctance to name the Samaritan.[9] Or, on another, more positive note, it may indicate that the lawyer has recognized that both his questions have been answered and now concludes by generally expressing that anyone behaving thus is a (Lev 19:18) "neighbor" eligible to inherit eternal life.[10] The Samaritans in turn hated the Jews.[11] Tensions were particularly high in the early decades of the 1st century because Samaritans had desecrated the Jewish Temple at Passover with human bones.[12]

As the story reached those who were unaware of the oppression of the Samaritans, this aspect of the parable became less and less discernible: fewer and fewer people ever heard of them in any context other than as a description. Today, the story is often recast in a more modern setting where the people are ones in equivalent social groups known not to interact comfortably. Thus, cast appropriately, the parable regains its message to modern listeners: namely, that an individual of a social group they disapprove of can exhibit moral behavior that is superior to individuals of the groups they approve. Christians have used it as an example of Christianity's opposition to racial, ethnic, and sectarian prejudice.[13][14] For example, anti-slavery campaigner William Jay described clergy who ignored slavery as "following the example of the priest and Levite".[15] Martin Luther King, Jr., in his "I've Been to the Mountaintop" speech, described the Samaritan as "a man of another race".[16] Sundee Tucker Frazier saw the Samaritan more specifically as an example of a "mixed-race" person.[17] Klyne Snodgrass wrote: "On the basis of this parable we must deal with our own racism but must also seek justice for, and offer assistance to, those in need, regardless of the group to which they belong."[18]

Samaritans appear elsewhere in the Gospels and Book of Acts. In the Gospel of Luke, Jesus heals ten lepers and only the Samaritan among them thanks him (Luke 17:11–19),[12] although Luke 9:51–56 depicts Jesus receiving a hostile reception in Samaria.[7] Luke's favorable treatment of Samaritans is in line with Luke's favorable treatment of the weak and of outcasts, generally.[19] In John, Jesus has an extended dialogue with a Samaritan woman, and many Samaritans come to believe in him.[20] In Matthew, however, Jesus instructs his disciples not to preach in heathen or Samaritan cities (Matthew 10:5–8).[12] In the Gospels, generally, "though the Jews of Jesus' day had no time for the 'half-breed' people of Samaria",[21] Jesus "never spoke disparagingly about them"[21] and "held a benign view of Samaritans".[22]

Many see 2 Chronicles 28:8–15 as the model for the Samaritan's neighborly behavior in the parable. In Chronicles, Northern Israelite ancestors of Samaritans treat Judean enemies as fellow-Israelite neighbors.[23] After comparing the earlier account with the later parable presented to the expert in Israel's religious law, Evans concludes: "Given the number and significance of these parallels and points of correspondence it is hard to imagine how a first-century scholar of Scripture could hear the parable and not think of the story of the merciful Samaritans of 2 Chronicles 28."[24]

Priests and Levites[edit]

In Jewish culture, contact with a dead body was understood to be defiling.[12] Priests were particularly enjoined to avoid uncleanness.[12] The priest and Levite may therefore have assumed that the fallen traveler was dead and avoided him to keep themselves ritually clean.[12] On the other hand, the depiction of travel downhill (from Jerusalem to Jericho) may indicate that their temple duties had already been completed, making this explanation less likely,[25] although this is disputed.[7] Since the Mishnah made an exception for neglected corpses,[7] the priest and the Levite could have used the law to justify both touching a corpse and ignoring it.[7] In any case, passing by on the other side avoided checking "whether he was dead or alive".[26] Indeed, "it weighed more with them that he might be dead and defiling to the touch of those whose business was with holy things than that he might be alive and in need of care."[26]

Interpretation[edit]

Allegorical reading[edit]

Origen described the allegory as follows:

The man who was going down is Adam. Jerusalem is paradise, and Jericho is the world. The robbers are hostile powers. The priest is the Law, the Levite is the prophets, and the Samaritan is Christ. The wounds are disobedience, the beast is the Lord's body, the [inn], which accepts all who wish to enter, is the Church. ... The manager of the [inn] is the head of the Church, to whom its care has been entrusted. And the fact that the Samaritan promises he will return represents the Savior's second coming.[27]

John Welch further states:

This allegorical reading was taught not only by ancient followers of Jesus, but it was virtually universal throughout early Christianity, being advocated by Irenaeus, Clement, and Origen, and in the fourth and fifth centuries by Chrysostom in Constantinople, Ambrose in Milan, and Augustine in North Africa. This interpretation is found most completely in two other medieval stained-glass windows, in the French cathedrals at Bourges and Sens."[28]

The allegorical interpretation is also traditional in the Orthodox Church.[29] John Newton refers to the allegorical interpretation in his hymn "How Kind the Good Samaritan", which begins:

How kind the good Samaritan

To him who fell among the thieves!

Thus Jesus pities fallen man,

And heals the wounds the soul receives.[30]

Robert Funk also suggests that Jesus' Jewish listeners were to identify with the robbed and wounded man. In his view, the help received from a hated Samaritan is like the kingdom of God received as grace from an unexpected source.[31]

Ethical reading[edit]

John Calvin was not impressed by Origen's allegorical reading:

The allegory which is here contrived by the advocates of free will is too absurd to deserve refutation. According to them, under the figure of a wounded man is described the condition of Adam after the fall; from which they infer that the power of acting well was not wholly extinguished in him; because he is said to be only half-dead. As if it had been the design of Christ, in this passage, to speak of the corruption of human nature, and to inquire whether the wound which Satan inflicted on Adam were deadly or curable; nay, as if he had not plainly, and without a figure, declared in another passage, that all are dead, but those whom he quickens by his voice (John 5:25). As little plausibility belongs to another allegory, which, however, has been so highly satisfactory, that it has been admitted by almost universal consent, as if it had been a revelation from heaven. This Samaritan they imagine to be Christ, because he is our guardian; and they tell us that wine was poured, along with oil, into the wound, because Christ cures us by repentance and by a promise of grace. They have contrived a third subtlety, that Christ does not immediately restore health, but sends us to the Church, as an innkeeper, to be gradually cured. I acknowledge that I have no liking for any of these interpretations; but we ought to have a deeper reverence for Scripture than to reckon ourselves at liberty to disguise its natural meaning. And, indeed, any one may see that the curiosity of certain men has led them to contrive these speculations, contrary to the intention of Christ.[32]

Francis Schaeffer suggested: "Christians are not to love their believing brothers to the exclusion of their non-believing fellowmen. That is ugly. We are to have the example of the good Samaritan consciously in mind at all times."[33]

Other modern theologians have taken similar positions. For example, G. B. Caird wrote:

Dodd quotes as a cautionary example Augustine's allegorisation of the Good Samaritan, in which the man is Adam, Jerusalem the heavenly city, Jericho the moon – the symbol of immortality; the thieves are the devil and his angels, who strip the man of immortality by persuading him to sin and so leave him (spiritually) half dead; the priest and Levite represent the Old Testament, the Samaritan Christ, the beast his flesh which he assumed at the Incarnation; the inn is the church and the innkeeper the apostle Paul. Most modern readers would agree with Dodd that this farrago bears no relationship to the real meaning of the parable.[34]

The meaning of the parable for Calvin was, instead, that "compassion, which an enemy showed to a Jew, demonstrates that the guidance and teaching of nature are sufficient to show that man was created for the sake of man. Hence it is inferred that there is a mutual obligation between all men."[32] In other writings, Calvin pointed out that people are not born merely for themselves, but rather "mankind is knit together with a holy knot ... we must not live for ourselves, but for our neighbors."[35] Earlier, Cyril of Alexandria had written that "a crown of love is being twined for him who loves his neighbour."[36]

Joel B. Green writes that Jesus' final question (which, in something of a "twist",[37] reverses the question originally asked):

... presupposes the identification of "anyone" as a neighbor, then presses the point that such an identification opens wide the door of loving action. By leaving aside the identity of the wounded man and by portraying the Samaritan traveler as one who performs the law (and so as one whose actions are consistent with an orientation to eternal life), Jesus has nullified the worldview that gives rise to such questions as, Who is my neighbor? The purity-holiness matrix has been capsized. And, not surprisingly in the Third Gospel, neighborly love has been concretized in care for one who is, in this parable, self-evidently a social outcast[38]

Such a reading of the parable makes it important in liberation theology,[39] where it provides a concrete anchoring for love[40] and indicates an "all embracing reach of solidarity."[41] In Indian Dalit theology, it is seen as providing a "life-giving message to the marginalized Dalits and a challenging message to the non-Dalits."[42]

Martin Luther King, Jr. often spoke of this parable, contrasting the rapacious philosophy of the robbers, and the self-preserving non-involvement of the priest and Levite, with the Samaritan's coming to the aid of the man in need.[43] King also extended the call for neighborly assistance to society at large:

On the one hand we are called to play the good Samaritan on life's roadside; but that will be only an initial act. One day we must come to see that the whole Jericho road must be transformed so that men and women will not be constantly beaten and robbed as they make their journey on life's highway. True compassion is more than flinging a coin to a beggar; it is not haphazard and superficial. It comes to see that an edifice which produces beggars needs restructuring.[44]

Other interpretations[edit]

In addition to these classical interpretations many scholars have drawn additional themes from the story. Some have suggested that religious tolerance was an important message of the parable. By selecting for the moral protagonist of the story someone whose religion (Samaritanism) was despised by the Jewish audience to which Jesus was speaking, some argue that the parable attempts to downplay religious differences in favor of focusing on moral character and good works.[45]

Others have suggested that Jesus was attempting to convey an anti-establishment message, not necessarily in the sense of rejecting authority figures in general, but in the sense of rejecting religious hypocrisy. By contrasting the noble acts of a despised religion to the crass and selfish acts of a priest and a Levite, two representatives of the Jewish religious establishment, some argue that the parable attempts to downplay the importance of status in the religious hierarchy (or importance of knowledge of scripture) in favor of the practice of religious principles.[46]

Modern Jewish view[edit]

- The following is based on the public domain article "Brotherly Love" found in the 1906 Jewish Encyclopedia.

The story of the good Samaritan, in the Pauline Gospel of Luke x. 25–37, related to illustrate the meaning of the word "neighbor", possesses a feature which puzzles the student of rabbinical lore. The kind Samaritan who comes to the rescue of the men that had fallen among the robbers, is contrasted with the unkind priest and Levite; whereas the third class of Jews—i.e., the ordinary Israelites who, as a rule, follow the Cohen and the Levite are omitted; and therefore suspicion is aroused regarding the original form of the story. If "Samaritan" has been substituted by the anti-Judean gospel-writer for the original "Israelite", no reflection was intended by Jesus upon Jewish teaching concerning the meaning of neighbor; and the lesson implied is that he who is in need must be the object of our love.

The term "neighbor" has not at all times been thus understood by Jewish teachers.[47] In Tanna debe Eliyahu R. xv. it is said: "Blessed be the Lord who is impartial toward all. He says: 'Thou shalt not defraud thy neighbor. Thy neighbor is like thy brother, and thy brother is like thy neighbor.'" Likewise in xxviii.: "Thou shalt love the Lord thy God"; that is, thou shalt make the name of God beloved to the creatures by a righteous conduct toward Gentiles as well as Jews (compare Sifre, Deut. 32). Aaron b. Abraham ibn Ḥayyim of the sixteenth century, in his commentary to Sifre, l.c.; Ḥayyim Vital, the cabalist, in his "Sha'are Ḳedushah", i. 5; and Moses Ḥagis of the eighteenth century, in his work on the 613 commandments, while commenting on Deut. xxiii. 7, teach alike that the law of love of the neighbor includes the non-Israelite as well as the Israelite. There is nowhere a dissenting opinion expressed by Jewish writers. For modern times, see among others the conservative opinion of Plessner's religious catechism, "Dat Mosheh we-Yehudit", p. 258.

Accordingly, the synod at Leipzig in 1869, and the German-Israelitish Union of Congregations in 1885, stood on old historical ground when declaring (Lazarus, "Ethics of Judaism", i. 234, 302) that "'Love thy neighbor as thyself' is a command of all-embracing love, and is a fundamental principle of the Jewish religion"; and Stade, when charging with imposture the rabbis who made this declaration, is entirely in error (see his "Geschichte des Volkes Israel", l.c.).

Authenticity[edit]

The Jesus Seminar voted this parable to be authentic,[48][49] with 60% of fellows rating it "red" (authentic) and a further 29% rating it "pink" (probably authentic).[49] The paradox of a disliked outsider such as a Samaritan helping a Jew is typical of Jesus' provocative parables,[48][7] and is a deliberate feature of this parable.[50] In the Greek text, the shock value of the Samaritan's appearance is enhanced by the emphatic Σαμαρίτης (Samaritēs) at the beginning of the sentence in verse 33.[7]

Bernard Brandon Scott, a member of the Jesus Seminar,[51] questions the authenticity of the parable's context, suggesting that "the parable originally circulated separately from the question about neighborliness"[52] and that the "existence of the lawyer's question in Mark 12:28–34 and Matthew 22:34–40, in addition to the evidence of heavy Lukan editing"[52] indicates the parable and its context were "very probably joined editorially by Luke."[52] A number of other commentators share this opinion,[53] with the consensus of the Jesus Seminar being that verses Luke 10:36–37 were added by Luke to "connect with the lawyer's question."[49] On the other hand, the "keen rabbinic interest in the question of the greatest commandment"[53] may make this argument invalid, in that Luke may be describing a different occurrence of the question being asked.[53] Differences between the gospels suggest that Luke is referring to a different episode from Mark and Matthew,[54] and Klyne Snodgrass writes that "While one cannot exclude that Luke has joined two originally separate narratives, evidence for this is not convincing."[54] The Oxford Bible Commentary notes:

That Jesus was only tested once in this way is not a necessary assumption. The twist between the lawyer's question and Jesus' answer is entirely in keeping with Jesus' radical stance: he was making the lawyer rethink his presuppositions.[37]

The unexpected appearance of the Samaritan led Joseph Halévy to suggest that the parable originally involved "a priest, a Levite, and an Israelite",[50] in line with contemporary Jewish stories, and that Luke changed the parable to be more familiar to a gentile audience."[50] Halévy further suggests that, in real life, it was unlikely that a Samaritan would actually have been found on the road between Jericho and Jerusalem,[50] although others claim that there was "nothing strange about a Samaritan travelling in Jewish territory".[9] William C. Placher points out that such debate misinterprets the biblical genre of a parable, which illustrates a moral rather than a historical point: on reading the story, "we are not inclined to check the story against the police blotter for the Jerusalem-Jericho highway patrol. We recognize that Jesus is telling a story to illustrate a moral point, and that such stories often don't claim to correspond to actual events."[55] The traditionally understood ethical moral of the story would not hold if the parable originally followed the priest-Levite-Israelite sequence of contemporary Jewish stories, as Halévy suggested, for then it would deal strictly with intra-Israelite relations just as did the Lev 19:18 command under discussion.

As a metaphor and name[edit]

The term "good Samaritan" is used as a common metaphor: "The word now applies to any charitable person, especially one who, like the man in the parable, rescues or helps out a needy stranger."[56]

The name has consequently been used for a number of charitable organisations, including Samaritans, Samaritan's Purse, Sisters of the Good Samaritan, and The Samaritan Befrienders Hong Kong. The name Good Samaritan Hospital is used for a number of hospitals around the world. Good Samaritan laws encourage those who choose to serve and tend to others who are injured or ill.[57]

Art and popular culture[edit]

This parable was one of the most popular in medieval art.[58] The allegorical interpretation was often illustrated, with Christ as the Good Samaritan. Accompanying angels were sometimes also shown.[59] In some Orthodox icons of the parable, the identification of the Good Samaritan as Christ is made explicit with a halo bearing a cross.[60]

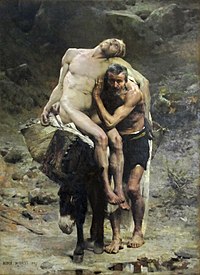

The numerous later artistic depictions of the parable include those of Rembrandt, Jan Wijnants, Vincent van Gogh, Aimé Morot, Domenico Fetti, Johann Carl Loth, George Frederic Watts, and Giacomo Conti. Vincent van Gogh's painting captures the reverse hierarchy that is underscored in Luke's parable. Although the priest and Levite are near the top of the status hierarchy in Israel and the Samaritans near the bottom, van Gogh reverses this hierarchy in the painting. He foregrounds the Samaritan, making him larger than life and colorful, while the priest and Levite are placed in the background, making them small and insignificant, barely distinguished from the drab landscape.[61]

In his essay Lost in Non-Translation, biochemist and author Isaac Asimov argues that to the Jews of the time there were no good Samaritans; in his view, this was half the point of the parable. As Asimov put it, we need to think of the story occurring in Alabama in 1950, with a mayor and a preacher ignoring a man who has been beaten and robbed, with the role of the Samaritan being played by a poor black sharecropper.

The story's theme is portrayed throughout Marvel's Daredevil.[62]

The parable of the Good Samaritan is the theme for the Austrian Christian Charity commemorative coin, minted 12 March 2003. This coin shows the Good Samaritan with the wounded man, on his horse, as he takes him to an inn for medical attention. An older coin with this theme is the American "Good Samaritan Shilling" of 1652.[63]

Australian poet Henry Lawson wrote a poem on the parable ("The Good Samaritan"), of which the third stanza reads:

He's been a fool, perhaps, and would

Have prospered had he tried,

But he was one who never could

Pass by the other side.

An honest man whom men called soft,

While laughing in their sleeves—

No doubt in business ways he oft

Had fallen amongst thieves.[64]

John Gardiner Calkins Brainard[65] also wrote a poem on the theme.

Dramatic film adaptations of the Parable of the Good Samaritan include Samaritan,[66] part of the widely acclaimed[67] Modern Parables DVD Bible study series. Samaritan, which sets the parable in modern times, stars Antonio Albadran in the role of the Good Samaritan.[68]

The English composer, Benjamin Britten, was commissioned to write a piece to mark the centenary of the Red Cross. His resulting work for solo voices, choir, and orchestra, Cantata Misericordium, sets a Latin text by Patrick Wilkinson that tells the parable of the Good Samaritan. It was first performed in Geneva in 1963.[69]

In a real-life psychology experiment, seminary students in a rush to teach on this parable, failed to stop to help a shabbily dressed person on the side of the road.[70]

The good Samaritan, after Delacroix by Van Gogh, 1890

Legal presence[edit]

In the English law of negligence, when establishing a duty of care in Donoghue v Stevenson Lord Atkin applied the neighbour principle—drawing inspiration from the Biblical Golden Rule[72] as in the parable of the Good Samaritan.

See also[edit]

- Brotherly Love

- Bystander effect

- Christian ethics

- Christian–Jewish reconciliation

- Golden Rule

- Great Commandment

- Life of Jesus in the New Testament

- Matthew 5

- Ministry of Jesus

- Digital samaritans

- Samaritans

References[edit]

- ^ Luke 10:25–37.

- ^ Gill, John (1980). An Exposition of the Old Testament. Baker Books. ISBN 978-0801037566.

- ^ a b Caird, G. B. (1980). The Language and Imagery of the Bible. Duckworth. p. 165.

- ^ Sanders, E. P. The historical figure of Jesus. Penguin, 1993. p. 6.

- ^ Wilkinson, "The Way from Jerusalem to Jericho" The Biblical Archaeologist, Vol. 38, No. 1 (Mar., 1975), pp. 10–24

- ^ Martin Luther King, Jr: "I've Been to the Mountaintop", delivered 3 April 1968, Memphis, Tennessee [1]

- ^ a b c d e f g Greg W. Forbes, The God of Old: The role of the Lukan parables in the purpose of Luke's Gospel, Continuum, 2000, ISBN 1-84127-131-4, pp. 63–64.

- ^ An event which the first-century historian Josephus records (J.W. 13.9.1 §256). For a different opinion, see Jonathan Bourgel (2016). "The Destruction of the Samaritan Temple by John Hyrcanus: A Reconsideration". Journal of Biblical Literature. Society of Biblical Literature. 135 (153/3): 505. doi:10.15699/jbl.1353.2016.3129.

- ^ a b I. Howard Marshall, The Gospel of Luke: A commentary on the Greek text, Eerdmans, 1978, ISBN 0-8028-3512-0, p. 449-450.

- ^ See, e.g., Lane's argument that the lawyer positively alludes to Exod 34:6, with the word in 10:37a usually translated "mercy" (ἔλεος) actually referencing Septuagintal translation of the Hebrew word חסד, "covenantal loyalty", in Nathan Lane, "An Echo of Mercy: A Rereading of the Parable of the Good Samaritan", in Early Christian Literature and Intertextuality. Volume 2: Exegetical Studies (ed. C. A. Evans and H. D. Zacharias; Library of New Testament Studies 392; London: T&T Clark, 2009), 74-84.

- ^ Christianity by Sue Penney 1995 ISBN 0-435-30466-6 page 28

- ^ a b c d e f Vermes, Geza. The authentic gospel of Jesus. London, Penguin Books. 2004. p. 152-154.

- ^ Karl Barth's theological exegesis by Richard E. Burnett 2004 ISBN 0-8028-0999-5 pages 213–215

- ^ Prejudice and the People of God: How Revelation and Redemption Lead to Reconciliation by A. Charles Ware 2001 ISBN 0-8254-3946-9 page 16

- ^ William Jay, Miscellaneous Writings on Slavery, John P. Jewett & Company, 1853.

- ^ Martin Luther King, Jr: "I've Been to the Mountaintop", delivered 3 April 1968, Memphis, Tennessee at Stanford University [notes on exact altitudes added, interjections removed].

- ^ Sundee Tucker Frazier, Check all that apply: finding wholeness as a multiracial person, InterVarsity Press, 2002, ISBN 0-8308-2247-X, p. 6.

- ^ Snodgrass, Klyne, Stories with Intent: A comprehensive guide to the parables of Jesus, Eerdmans, 2008, ISBN 0-8028-4241-0, p. 361.

- ^ Theissen, Gerd and Annette Merz. The historical Jesus: a comprehensive guide. Fortress Press. 1998. translated from German (1996 edition). Chapter 2. Christian sources about Jesus.

- ^ Funk, Robert W., Roy W. Hoover, and the Jesus Seminar. The five gospels. HarperSanFrancisco. 1993. "The Gospel of John", pp. 401–470.

- ^ a b Stanley A. Ellisen, Parables in the Eye of the Storm: Christ's Response in the Face of Conflict, Kregel Publications, 2001, ISBN 0-8254-2527-1, p. 142.

- ^ John P. Meier, "The Historical Jesus and the Historical Samaritans: What can be Said?", Biblica 81(2), 2000, pp. 202–232 (quote from p. 231).

- ^ See, e.g., Frank H. Wilkinson, "Oded: Proto-Type of the Good Samaritan", The Expository Times 69 (1957): 94; F. Scott Spencer, "2 Chronicles 28:5–15 and the Parable of the Good Samaritan", Westminster Theological Journal 46 (1984): 317–49; Geza Vermes, The Authentic Gospel of Jesus (London: Penguin, 2004), 152; Isaac Kalimi, "Robbers on the Road to Jericho: Luke's Story of the Good Samaritan and Its Origin in Kings / Chronicles", Ephemerides theologicae lovanienses 85 (2009): 47–53; Craig A. Evans, "Luke's Good Samaritan and the Chronicler's Good Samaritans", in Biblical Interpretation in Early Christian Gospels. Volume 3: The Gospel of Luke (ed. Thomas R. Hatina; Library of New Testament Studies 376 / Studies in Scripture in Early Judaism and Christianity 16; London and New York: T&T Clark, 2010), 32–42; Michael Fresta, "'Hüter des Bundes' und 'Diener des Herrn' – Samaritaner und Samaritanerinnen im Neuen Testament: Historische und neutestamentlich-exegetische Untersuchungen" (Ph.D. diss., University of Paderborn, 2011), 150–52, 253; Amy-Jill Levine, "The Many Faces of the Good Samaritan—Most Wrong", Christian Ethics Today 85:1 (Winter 2012): 20–21 (see earlier version at http://www.biblicalarchaeology.org/daily/archaeology-today/archaeologists-biblical-scholars-works/understanding-the-good-samaritan-parable/; accessed 1 Oct 2016); Eben Scheffler, "The Assaulted (Man) on the Jerusalem - Jericho Road : Luke's Creative Interpretation of 2 Chronicles 28:15", Hervormde teologiese studies 69 (2013): 1–8; online: http://www.scielo.org.za/scielo.php?script=sci_abstract&pid=S0259-94222013000100121&lng=en&nrm=iso&tlng=en (accessed 1 Oct 2016).

- ^ Evans, "Luke's Good Samaritan and the Chronicler's Good Samaritans", 39.

- ^ Joel B. Green, The Gospel of Luke, Eerdmans, 1997, ISBN 0-8028-2315-7, p. 430.

- ^ a b George Bradford Caird, The Gospel of St. Luke, Black, 1968, p. 148.

- ^ Origen, Homily 34.3, Joseph T. Lienhard, trans., Origen: Homilies on Mark, Fragments on Mark (1996), 138.

- ^ John W. Welch, "The Good Samaritan: Forgotten Symbols", Liahona, February 2007, pp. 26–33.

- ^ Christoph Cardinal Schonborn (tr. Henry Taylor), Jesus, the Divine Physician: Reflections on the Gospel During the Year of Luke, Ignatius Press, 2008, ISBN 1-58617-180-1, p. 16.

- ^ John Newton, "How Kind the Good Samaritan", Hymn #99 in Olney Hymns Archived 2010-08-10 at the Wayback Machine at CCEL.org.

- ^ Theissen, Gerd and Annette Merz. The historical Jesus: a comprehensive guide. Fortress Press. 1998. translated from German (1996 edition). p. 321-322

- ^ a b John Calvin, Commentary on Matthew, Mark, Luke – Volume 3.

- ^ Schaeffer, Francis (1970). The Mark of the Christian by Francis Schaeffer © 1970 by L'Abri Fellowship. Norfolk Press, London.

- ^ Caird, G. B. (1980). The Language and Imagery of the Bible. Duckworth. p. 165.

- ^ John Calvin, Commentary on Acts 13.

- ^ Cyril's Sermons on Luke #68.

- ^ a b John Barton and John Muddiman, The Oxford Bible Commentary, Oxford University Press, 2001, ISBN 0-19-875500-7, p. 942.

- ^ Joel B. Green, The Gospel of Luke, Eerdmans, 1997, ISBN 0-8028-2315-7, p. 432.

- ^ Christopher Hays, Luke's Wealth Ethics: A Study in Their Coherence and Character, Mohr Siebeck, 2010, ISBN 3-16-150269-8, p. 21.

- ^ Christopher Rowland, The Cambridge Companion to Liberation Theology, 2nd ed, Cambridge University Press, 2007, ISBN 0-521-86883-1, p. 43.

- ^ Denis Carroll, What is Liberation Theology?, Gracewing Publishing, 1987, ISBN 0-85342-812-3, p. 57.

- ^ M. Gnanavaram, "'Dalit Theology' and the Parable of the Good Samaritan", Journal for the Study of the New Testament, Vol. 15, No. 50, 59–83 (1993).

- ^ Taylor Branch, Pillar of Fire: America in the King Years, 1963–65, Simon and Schuster, 1998, ISBN 0-684-84809-0, pp.302–303.

- ^ Martin Luther King, Jr., "A Time to Break the Silence", quoted in Douglas A. Hicks and Mark R. Valeri, Global Neighbors: Christian Faith and Moral Obligation in Today's Economy, Eerdmans Publishing, 2008, ISBN 0-8028-6033-8, p. 31.

- ^ Smith, John Hunter (1884). Greek Testament lessons, consisting chiefly of the Sermon on the mount, and the parables of our Lord. With notes and essays. London, UK: William Blackwood and Sons. p. 136.

Clarke, James Freeman (1886). Every-day Religion. Boston: Ticknor and Company. p. 346. - ^ Andrews, Dave (2012). Not Religion but Love: Practicing a Radical Spirituality of Compassion. Wipf and Stock Publishers. p. 117. ISBN 9781610978514.

Wilson, Jared C. (2014). The Storytelling God: Seeing the Glory of Jesus in His Parables. Crossway. p. 88. ISBN 9781433536717. - ^ Several recognize that Lev 19:18 exclusively refers to the Israelitish neighbor (e.g., Stade, "Gesch. des Volkes Israel", i. 510a). This debate is reflected in the question by the Jewish Torah expert re the definition of "neighbor" in Lev 19:18 (Luke 10:29).

- ^ a b Funk, Robert W., Roy W. Hoover, and the Jesus Seminar. The five gospels. HarperSanFrancisco. 1993. "Luke" p. 271-400

- ^ a b c Peter Rhea Jones, Studying the Parables of Jesus, Smyth & Helwys, 1999, ISBN 1-57312-167-3, p. 294.

- ^ a b c d Bernard Brandon Scott, Hear Then the Parable: A commentary on the parables of Jesus, Fortress Press, 1989, ISBN 0-8006-2481-5, pp. 199–200.

- ^ Bernard Brandon Scott.

- ^ a b c Bernard Brandon Scott, Hear Then the Parable: A commentary on the parables of Jesus, Fortress Press, 1989, ISBN 0-8006-2481-5, pp. 191–192.

- ^ a b c Greg W. Forbes, The God of Old: The role of the Lukan parables in the purpose of Luke's Gospel, Continuum, 2000, ISBN 1-84127-131-4, pp. 56–57.

- ^ a b Klyne Snodgrass, Stories with Intent: A comprehensive guide to the parables of Jesus, Eerdmans, 2008, ISBN 0-8028-4241-0, p. 348.

- ^ William C. Placher, "Is the Bible True?" The Christian Century, October 11, 1995, pp. 924–925.

- ^ Dictionary of Classical, Biblical, & Literary Allusions

- ^ Mark Lunney and Ken Oliphant, Tort Law: Text and Materials, 3rd ed., Oxford University Press, 2008, ISBN 0-19-921136-1, p. 465.

- ^ Emile Mâle, The Gothic Image: Religious Art in France of the Thirteenth Century, p 195, English translation of 3rd ed, 1913, Collins, London (and many other editions), ISBN 978-0064300322

- ^ Leslie Ross, Medieval Art: A topical dictionary, Greenwood Publishing Group, 1996, ISBN 0-313-29329-5, p. 105.

- ^ Paul H. Ballard and Stephen R. Holmes, The Bible in Pastoral Practice: Readings in the place and function of Scripture in the church, Eerdmans, 2006, ISBN 0-8028-3115-X, p. 55.

- ^ James L. Resseguie, Narrative Criticism of the New Testament: An Introduction (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2005), 26-30 at p. 29.

- ^ Meagan Damore, Anatomy of a Villain: The Secret of the Success of "Daredevil's" Kingpin, cbr.com, 06.01.2015 Retrieved 05.08.2018

- ^ Albert Romer Frey, A Dictionary of Numismatic Names: Their Official and Popular Designations, American Numismatic Society, 1917 (reprinted by BiblioLife, LLC, 2009), ISBN 1-115-68411-6, p. 95.

- ^ Henry Lawson, "The Good Samaritan", in When I Was King and Other Verses, first published 1905.

- ^ John Gardiner Calkins Brainard, Occasional Pieces of Poetry, E. Bliss and E. White, 1825, pp. 79–81.

- ^ Samaritan at Modern Parables web site.

- ^ See e.g., "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2008-05-13. Retrieved 2008-10-10.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link),"Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2011-07-12. Retrieved 2009-01-31.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link), [2]

- ^ Samaritan at IMDB.

- ^ http://www.boosey.com/cr/music/Benjamin-Britten-Cantata-Misericordium/4926&langid=1 Cantata Misericordium at Boosey and Hawkes

- ^ Darley, John M.; Batson, C. Daniel (1973). ""From Jerusalem to Jericho": A study of Situational and Dispositional Variables in Helping Behavior". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 27 (1): 100–108. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.315.252. doi:10.1037/h0034449.

- ^ Roland E. Fleischer and Susan C. Scott, Rembrandt, Rubens, and the Art of their Time: Recent perspectives, Pennsylvania State University Press, 1997, ISBN 0-915773-10-4, pp. 68–69.

- ^ "SCLR - Resources - Donoghue v. Stevenson Case Report". www.scottishlawreports.org.uk. Retrieved 2019-11-09.

External links[edit]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to The Good Samaritan. |

- Biblical art on the Internet:

- Good Samaritan websites:

- Good Samaritan Industries—Charity helping people with disabilities

- Good Samaritan Day—Promotes October 13 as "Good Samaritan Day"