Poul Anderson

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

(Learn how and when to remove this template message)

|

Poul Anderson | |

|---|---|

Anderson at Polcon in 1985 | |

| Born | Poul William Anderson November 25, 1926 Bristol, Pennsylvania, United States |

| Died | July 31, 2001 (aged 74) Orinda, California, United States[1][2] |

| Pen name | A. A. Craig Michael Karageorge Winston P. Sanders P. A. Kingsley[3] |

| Occupation | Writer |

| Nationality | USA |

| Period | 1948–2001 |

| Genre | Science fiction, fantasy, time travel, mystery, historical fiction |

| Notable works | |

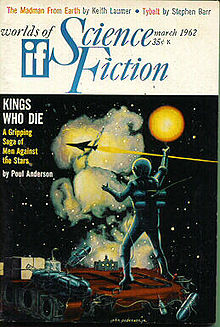

Poul William Anderson (November 25, 1926 – July 31, 2001)[4] was an American science fiction author who began his career in the 1940s and continued to write into the 21st century. Anderson authored several works of fantasy, historical novels, and short stories. His awards include seven Hugo Awards and three Nebula Awards.[5]

Biography[edit]

Poul Anderson was born on November 25, 1926, in Bristol, Pennsylvania, of Scandinavian parents.[6] Shortly after his birth, his father, Anton Anderson, an engineer, moved the family to Texas, where they lived for over ten years. Following Anton Anderson's death, his widow took her children to Denmark. The family returned to the United States after the outbreak of World War II, settling eventually on a Minnesota farm. The frame story of his later novel Three Hearts and Three Lions, before the fantasy part begins, is partly set in the Denmark which the young Anderson personally experienced.

While he was an undergraduate student at the University of Minnesota, Anderson's first stories were published by John W. Campbell in Astounding Science Fiction: "Tomorrow's Children" by Anderson and F. N. Waldrop in March 1947 and a sequel, "Chain of Logic" by Anderson alone, in July.[a] He earned his B.A. in physics with honors but made no serious attempt to work as a physicist; instead he became a free-lance writer after his graduation in 1948, and placed his third story in the December Astounding.[7]. While finding no purely academic application, Anderson's knowledge of physics is evident in the great care given to details of the scientific background – one of the defining characteristics of his writing style.

Anderson married Karen Kruse in 1953 and moved with her to the San Francisco Bay area. Their daughter Astrid (now married to science fiction author Greg Bear) was born in 1954. They made their home in Orinda, California. Over the years Poul gave many readings at The Other Change of Hobbit bookstore in Berkeley, and his wife later donated his typewriter and desk to the store.

In 1965 Algis Budrys said that Anderson "has for some time been science fiction's best storyteller".[8] He was a founding member of the Society for Creative Anachronism (SCA) in 1966 and of the Swordsmen and Sorcerers' Guild of America (SAGA), also in the mid-1960s. The latter was a loose-knit group of Heroic Fantasy authors led by Lin Carter, originally eight in number, with entry by credentials as a fantasy writer alone. Anderson was the sixth President of Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America, taking office in 1972.

Robert A. Heinlein dedicated his 1985 novel The Cat Who Walks Through Walls to Anderson and eight of the other members of the Citizens' Advisory Council on National Space Policy.[9][10] The Science Fiction Writers of America made Anderson its 16th SFWA Grand Master in 1998[11] and the Science Fiction and Fantasy Hall of Fame inducted him in 2000, its fifth class of two deceased and two living writers.[12] He died of prostate cancer on July 31, 2001, after a month in the hospital. A few of his novels were first published posthumously.

Political, moral and literary themes[edit]

This section possibly contains original research. (July 2009) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

Anderson is probably best known for adventure stories in which larger-than-life characters succeed gleefully or fail heroically. His characters were nonetheless thoughtful, often introspective, and well developed. His plot lines frequently involved the application of social and political issues in a speculative manner appropriate to the science fiction genre. He also wrote some quieter works, generally of shorter length, which appeared more often during the latter part of his career.

Much of his science fiction is thoroughly grounded in science (with the addition of unscientific but standard speculations such as faster-than-light travel). A specialty was imagining scientifically plausible non-Earthlike planets. Perhaps the best known was the planet of The Man Who Counts in which Anderson adjusted its size and composition so that humans could live in the open air but flying intelligent aliens could evolve, and he explored the consequences of those adjustments.

Space and liberty[edit]

In many stories, Anderson commented on society and politics. Whatever other vicissitudes his views went through, he firmly retained his belief in the direct and inextricable connection between human liberty and expansion into space, for which reason he strongly cried out against any idea of space exploration being "a waste of money" or "unnecessary luxury".

The connection between space flight and freedom is clearly (as is stated explicitly in some of the stories) an extension of the 19th-century American concept of the Frontier, where malcontents can advance further and claim some new land, and pioneers either bring life to barren asteroids (as in Tales of the Flying Mountains) or settle on Earth-like planets teeming with life, but not intelligent forms (such as New Europe in Star Fox).

As he repeatedly expressed in his nonfiction essays, Anderson firmly held that going into space was not an unnecessary luxury but an existential need, and that abandoning space would doom humanity to "a society of brigands ruling over peasants."

That is graphically expressed in the chilling short story "Welcome". In it, humanity has abandoned space and is left with an overcrowded Earth where a small elite not only treats all the rest as chattel slaves, but also regularly practices cannibalism, their chefs preparing "roast suckling coolie" for their banquets.

Conversely, in the bleak Orwellian world of "The High Ones" where the Soviets have won the Third World War and gained control of the whole of Earth, the dissidents still have some hope, precisely because space flight has not been abandoned. By the end of the story, rebels have established themselves at another stellar system—where their descendants, the reader is told, would eventually build a liberating fleet and set out back to Earth.

World government[edit]

While horrified by the prospect of the Soviets winning complete rule over the Earth, Anderson was not enthusiastic about having Americans in that role either. Several stories and books describing the aftermath of a total US victory in another world war, such as "Sam Hall" and its loose sequel "Three Worlds to Conquer" as well as "Shield", are scarcely less bleak than the above-mentioned depictions of a Soviet victory. Like Heinlein in "Solution Unsatisfactory", Anderson assumed that the imposition of US military rule over the rest of the world would necessarily entail the destruction of the USA's democracy and the imposition of a harsh tyrannical rule over its own citizens.

Both Anderson's depiction of a Soviet-dominated world and that of a US-dominated one mention a rebellion breaking out in Brazil in the early 21st century, which is in both cases brutally put down by the dominant world power—the Brazilian rebels being characterized as "counter-revolutionaries" in the one case and as "communists" in the other.

In the early years of the Cold War—when he had been, as described by his later, more conservative self, a "flaming liberal"—Anderson pinned his hopes on the United Nations developing into a true world government. This is especially manifest in "Un-man", a future thriller where the 'Good Guys' are agents of the UN Secretary General working to establish a world government while the 'Bad Guys' are nationalists (especially American nationalists) who seek to preserve their respective nations' sovereignty at all costs. (The title has a double meaning: the hero is literally an UN man and has superhuman abilities which make his enemies fear him as an "un-man").

Anderson and his wife were among those who in 1968 signed a pro-Vietnam War advertisement in Galaxy Science Fiction.[13] By then, Anderson had repudiated world government; a half-humorous remnant is the beginning of Tau Zero: a future in which the nations of the world entrusted Sweden with overseeing disarmament and found themselves living under the rule of the Swedish Empire. In The Star Fox, he unfavorably depicts a future peace group called "World Militants for Peace". A more explicit expression of the same appears in the later The Shield of Time where a time-traveling young American woman from the 1990s pays a brief visit to a university campus of the 1960s and is not enthusiastic about what she sees there.

Libertarianism[edit]

Anderson often returned to right-libertarianism and to the business leader as hero, most notably his character Nicholas van Rijn. Van Rijn is different from the archetype of a modern type of business executive, being more reflective of a Dutch Golden Age merchant of the 17th century. If he spends any time in boardrooms or plotting corporate takeovers, the reader remains ignorant of it since nearly all his appearances are in the wilds of a space frontier.

Beginning in the 1970s, Anderson's historically grounded works were influenced by the theories of the historian John K. Hord, who argued that all empires follow the same broad cyclical pattern, into which the Terran Empire of the Dominic Flandry spy stories fit neatly.

The writer Sandra Miesel (1978) has argued that Anderson's overarching theme is the struggle against entropy and the heat death of the universe, a condition of perfect uniformity in which nothing can happen.

Fairness to adversaries[edit]

In his numerous books and stories depicting conflict in science fiction or fantasy settings, Anderson takes trouble to make both sides' points of view comprehensible. Even if the author's point of view is obvious, the antagonists are usually depicted not as villains but as honorable on their own terms. The reader is given access to antagonists' thoughts and feelings, and they often have a tragic dignity in defeat. Typical examples are The Winter of the World and The People of the Wind.

A common theme in Anderson's works, with obvious origins in the Northern European legends, is that doing the "right" (wisest) thing often involves performing actions that at face value seem dishonorable, illegal, destructive, or downright evil. The Man who Counts, Nicholas van Rijn is "The Man" because he is prepared to be tyrannical and callously manipulative so that he and his companions can survive. In "High Treason", the protagonist disobeys orders and betrays his subordinates to prevent a war crime that would bring severe retribution upon humanity. In A Knight of Ghosts and Shadows, Dominic Flandry first (effectively) lobotomizes his own son and then bombards the home planet of the Chereionite race to do his duty and prop up the Terran Empire. Such actions affect their characters in different ways, and dealing with the repercussions of having done the "right" (but unpleasant) thing is often the major focus of his short stories. The general lesson seems to be that guilt is the penalty for action.

In The Star Fox, a relationship of grudging respect is built up between the hero, space privateer Gunnar Heim, and his enemy Cynbe, an exceptionally gifted Alerione trained from a young age to understand his species' human enemies to the point of being alienated from his own kind. In the final scene, Cynbe challenges Heim to a space battle which only one of them would survive. Heim accepts, whereupon Cynbe says, "I thank you, my brother."

Underestimation of "primitives" as a costly mistake[edit]

Anderson set much of his work in the past, often with the addition of magic or in alternate or future worlds that resemble past eras. A specialty was his ancestral Scandinavia, as in his novel versions of the legends of Hrólf Kraki (Hrolf Kraki's Saga) and Haddingus (The War of the Gods). Frequently he presented such worlds as superior to the dull, over-civilized present. Notable depictions of this superiority are the prehistoric world of The Long Remembering, the quasi-medieval society of "No Truce with Kings", and the untamed Jupiter of "Call Me Joe" and Three Worlds to Conquer. He handled the lure and power of atavism satirically in Pact, critically in "The Queen of Air and Darkness" and The Night Face, and tragically in "Goat Song".

His 1965 novel The Corridors of Time alternates between the European Stone Age and a repressive future. In this vision of tomorrow, almost everyone is either an agricultural serf or an industrial slave, but the rulers genuinely believe they are creating a better world. Set largely in Denmark, it treats the Neolithic society with knowledge and respect does but not hide its faults. The protagonist, having access to literally all periods of the past and future, finally decides to settle down in that era and finds a happy and satisfying life.

In many stories, a representative of a technologically advanced society underestimates "primitives" and pays a high price for it. In The High Crusade, aliens who land in medieval England in the expectation of an easy conquest find that they are not immune to swords and arrows. In "The Only Game in Town", a Mongol warrior, while not knowing that the two "magicians" he meets are time travelers from the future, correctly guesses their intentions—and captures them with the help of the "magic" flashlight they had given him in an attempt to impress him. In another time-travel tale, The Shield of Time, a "time policeman" from the 20th century, equipped with information and technologies from much further in the future, is outwitted by a medieval knight and barely escapes with his life. Yet another story, "The Man Who Came Early", features a 20th-century US Army soldier stationed in Iceland who is transported to the 10th century. Although he is full of ideas, his lack of practical knowledge of how to implement them and his total unfamiliarity with the technology and customs of the period leads to his downfall.

Anderson wrote the short essay "Uncleftish Beholding", an introduction to atomic theory, using only Germanic-rooted words. Fitting his love for olden years, that kind of learned writing has been named Ander-Saxon after him.

Tragic conflicts[edit]

The story told in The Shield of Time is also an example of a tragic conflict, another common theme in Anderson's writing. The knight tries to do his best in terms of his own society and time, but his actions might bring about a horrible 20th century (even more horrible than that actually occurred). Therefore, the Time Patrol protagonists, who like the young knight and wish him well (the female protagonist comes close to falling in love with him), have no choice but to fight and ultimately kill him.

In The Sorrow of Odin the Goth, a time-travelling anthropologist is assigned to study the culture of an ancient Gothic tribe by regular visits every few decades. Gradually, he is drawn into close involvement and feels protective towards the Goths (many of them are his own descendants because of a brief and poignant liaison with a Gothic, girl who dies in childbirth). The Goths identify him as the god Odin/Wodan. He finds that he must cruelly betray his beloved Goths since a ballad says that Odin did so; failure to fulfill his prescribed role might change history and bring the whole of the actual 20th century crashing down. In the final scene, he cries out in anguish: "Not even the gods can defy the Norns!", giving a new twist to that central aspect of the Norse religion.

In "The Pirate", the hero is duty-bound to deny a band of people from societies blighted by poverty the chance for a new start on a new planet since their settling the planet would eradicate the remnants of the artistic and articulate beings who lived there earlier. A similar theme but with much higher stakes appears in "Sister Planet": although terraforming Venus would provide new hope to starving people on the overcrowded Earth, it would exterminate Venus's just-discovered intelligent race, and the hero can avert that genocide only by murdering his best friends.

In "Delenda Est" the stakes are the highest imaginable. Time-travelling outlaws have created a new 20th century that is "not better or worse, just completely different". The hero can fight the outlaws and restore his (and our) familiar history but only at the price of totally destroying the vast world that has taken its place. "Risking your neck in order to negate a world full of people like yourself" is how the hero describes what he eventually undertakes.

Awards and honors[edit]

- Gandalf Grand Master of Fantasy (1978)[5]

- Hugo Award (seven times)[14]

- John W. Campbell Memorial Award (2000)[15]

- Locus Award (41 nominations; one win, 1972)[16]

- Mythopoeic Fantasy Award (one win (1975))[17]

- Nebula Award (three times)[18]

- Pegasus Award (best adaptation, with Anne Passovoy) (1998)

- Prometheus Award (four times, including Special Prometheus Award for Lifetime Achievement in 2001)

- SFWA Grand Master (1997)[11]

- Science Fiction and Fantasy Hall of Fame (2000)[12]

- Asteroid 7758 Poulanderson, discovered by Eleanor Helin at Palomar in 1990, was named in his honor.[19] The official naming citation was published by the Minor Planet Center shortly after his death on 2 September 2001 (M.P.C. 43381).[20]

Bibliography[edit]

Fictional appearances[edit]

Philip K. Dick's story "Waterspider" features Poul Anderson as one of the main characters.

In the opening of S.M. Stirling's novel In the Courts of the Crimson Kings, a group of science fiction authors, including Poul Anderson, watch first contact with the book's Martians while attending an SF convention. Anderson supplies the beer.

Notes[edit]

- ^ Anderson continued his first two stories more than a decade later. He added a novella and an epilogue, constituting the collection of four pieces (termed a novel), Twilight World: A Science Fiction Novel of Tomorrow's Children (Dodd, Mead). Waldrop was not credited.[7]

References[edit]

- ^ Douglas Martin (August 3, 2001). "Poul Anderson, Science Fiction Novelist, Dies at 74". The New York Times. Retrieved October 24, 2018.

- ^ Harris M. Lentz III (October 24, 2008). Obituaries in the Performing Arts, 2001: Film, Television, Radio, Theatre ... ISBN 9780786452064. Retrieved October 24, 2018.

- ^ Lee Gold. "Tracking Down The First Deliberate Use Of "Filk Song"". Retrieved August 11, 2007.

- ^ David V Barrett (August 4, 2001). "Obituary: Poul Anderson (Prolific writer of science fiction's golden age)". The Guardian. Retrieved October 25, 2018.

- ^ a b "Anderson, Poul" Archived 2012-10-16 at the Wayback Machine. The Locus Index to SF Awards: Index of Literary Nominees. Locus Publications. Retrieved 2013-03-22.

- ^ Tau Zero, SF Masterworks edition.

- ^ a b Poul Anderson at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database (ISFDB). Retrieved 2013-04-22. Select a title to see its linked publication history and general information. Select a particular edition (title) for more data at that level, such as a front cover image or linked contents.

- ^ Budrys, Algis (February 1965). "Galaxy Bookshelf". Galaxy Science Fiction. pp. 153–159.

- ^ Heinlein, Robert A (1986). The Cat Who Walks Through Walls. New England Library. ISBN 0-450-39315-1.

- ^ Heinlein's Dedications Page Jane Davitt & Tim Morgan. Retrieved 2008-08-20.

- ^ a b "Damon Knight Memorial Grand Master" Archived 2011-07-01 at the Wayback Machine. Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America (SFWA). Retrieved 2013-03-22.

- ^ a b "Science Fiction and Fantasy Hall of Fame" Archived 2013-05-21 at the Wayback Machine. Mid American Science Fiction and Fantasy Conventions, Inc. Retrieved 2013-03-22. This was the official website of the hall of fame to 2004.

- ^ "Paid Advertisement". Galaxy Science Fiction. June 1968. pp. 4–11.

- ^ "Science Fiction & Fantasy Books by Award: Complete Hugo Award novel listing". Worlds Without End. Retrieved March 28, 2009.

- ^ "Science Fiction & Fantasy Books by Award: 2000 Award Winners & Nominees". Worlds Without End. Retrieved March 28, 2009.

- ^ "Anderson, Poul". The Locus Index to SF Awards: Locus Award Nominees List. Locus Publications. Archived from the original on May 14, 2012. Retrieved August 24, 2009.

- ^ "Mythopoeic Society Award Winners". Mythopoeic Society. Archived from the original on October 6, 2014. Retrieved March 6, 2011.

- ^ "Science Fiction & Fantasy Books by Award: The Nebula Award". Worlds Without End. Retrieved March 28, 2009.

- ^ "7758 Poulanderson (1990 KT)". Minor Planet Center. Retrieved November 21, 2019.

- ^ "MPC/MPO/MPS Archive". Minor Planet Center. Retrieved November 21, 2019.

- Miesel, Sandra (1978). Against Time's Arrow: The High Crusade of Poul Anderson. Borgo Press. ISBN 0-89370-124-6.

- Tuck, Donald H. (1974). The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction and Fantasy. Chicago: Advent. pp. 8–10. ISBN 0-911682-20-1.

External links[edit]

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Poul Anderson |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Poul Anderson. |

- Bio, bibliography and book covers at FantasticFiction

- Obituary and tributes from the SFWA[dead link]

- Poul Anderson Appreciation, by Dr. Paul Shackley

- Poul Anderson, an essay by William Tenn

- The Society for Creative Anachronism, of which Poul Anderson was a founding member

- The King of Ys review at FantasyLiterature.net

- "Poul Anderson biography". Science Fiction and Fantasy Hall of Fame.

- Poul Anderson at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database

- Poul Anderson at the Internet Book List

- Poul Anderson at Curlie

- Poul Anderson at Library of Congress Authorities, with 134 catalog records

- By Poul Anderson

- Works by Poul Anderson at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Poul Anderson at Internet Archive

- Works by Poul Anderson at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Works by Poul Anderson at Open Library

- On Thud and Blunder, an essay by Anderson on fantasy fiction, from the SFWA

- Poul Anderson's online fiction at Free Speculative Fiction Online

- SFWA directory of literary estates

- 1926 births

- 2001 deaths

- American fantasy writers

- American alternate history writers

- American male novelists

- American people of Danish descent

- American science fiction writers

- Conan the Barbarian novelists

- Filkers

- Hugo Award-winning writers

- Nebula Award winners

- People from Bristol, Pennsylvania

- Science Fiction Hall of Fame inductees

- SFWA Grand Masters

- University of Minnesota alumni

- Novelists from Pennsylvania

- Writers from the San Francisco Bay Area

- Society for Creative Anachronism

- 20th-century American novelists

- 20th-century American male writers

- 21st-century American novelists

- People from Orinda, California

- American libertarians

- Pulp fiction writers