Slavic paganism

Slavic paganism or Slavic religion describes the religious beliefs, myths and ritual practices of the Slavs prior to Christianisation. The latter occurred at various stages between the 8th and the 13th century:[1] The South Slavs living on the Balkan Peninsula in South Eastern Europe, bordering with the Byzantine Empire to the south, came under the sphere of influence of Eastern Orthodox Christianity, beginning with the creation of writing systems for Slavic languages (first Glagolitic, and then Cyrillic script) in 855 by the brothers Saints Cyril and Methodius and the adoption of Christianity in Bulgaria in 863 AD. The East Slavs followed with the official adoption in 988 AD by Vladimir the Great of Kievan Rus'.[2]

The West Slavs came under the sphere of influence of the Roman Catholic Church starting in the 12th century, and Christianisation for them went hand in hand with full or partial Germanisation.[3]

The Christianisation of the Slavic peoples was, however, a slow and—in many cases—superficial phenomenon, especially in what is today Russia. Christianisation was vigorous in western and central parts of what is today Ukraine, as they were closer to the capital Kiev, but even there, popular resistance led by volkhvs, pagan priests or shamans, recurred periodically for centuries.[2]

The West Slavs of the Baltic withstood tenaciously against Christianity until it was violently imposed on them through the Northern Crusades.[3] Among Poles and East Slavs, rebellion outbreaks occurred throughout the 11th century.[1] Christian chroniclers reported that the Slavs regularly re-embraced their original religion (relapsi sunt denuo ad paganismus).[4]

Many elements of the indigenous Slavic religion were officially incorporated into Slavic Christianity,[2] and, besides this, the worship of Slavic gods has persisted in unofficial folk religion until modern times.[5] The Slavs' resistance to Christianity gave rise to a "whimsical syncretism" which in Old Church Slavonic vocabulary was defined as dvoeverie, "double faith".[1] Since the early 20th century, Slavic folk religion has undergone an organised reinvention and reincorporation in the movement of Slavic Native Faith (Rodnovery).

Overview and common features[edit]

Twentieth-century scholars who pursued the study of ancient Slavic religion include Vyacheslav Ivanov, Vladimir Toporov, Marija Gimbutas, Boris Rybakov,[7] and Roman Jakobson amongst others. Rybakov is noted for his effort to re-examine medieval ecclesiastical texts, synthesizing his findings with archaeological data, comparative mythology, ethnography, and nineteenth-century folk practices. He also elaborated one of the most coherent pictures of ancient Slavic religion in his Paganism of the Ancient Slavs and other works.[8] Among earlier, nineteenth-century scholars there was Bernhard Severin Ingemann, known for his study of Fundamentals of a North Slavic and Wendish mythology.

Historical documents about Slavic religion include the Primary Chronicle, compiled in Kiev around 1111, and the Novgorod First Chronicle compiled in the Novgorod Republic. They contain detailed reports of the annihilation of the official Slavic religion of Kiev and Novgorod, and the subsequent "double faith". The Primary Chronicle also contains the authentic text of Rus-Greek treatises (dated 945 and 971) with native pre-Christian oaths. From the eleventh century onwards, various Rus writings were produced against the survival of Slavic religion, and Slavic gods were interpolated in the translations of foreign literary works, such as the Malalas Chronicle and the Alexandreis.[1]

The West Slavs who dwelt in the area between the Vistula and the Elbe stubbornly resisted the Northern Crusades, and the history of their resistance is written down in the Latin Chronicles of three German clergymen—Thietmar of Merseburg and Adam of Bremen in the eleventh century and Helmold in the twelfth—, in the twelfth-century biographies of Otto of Bamberg, and in Saxo Grammaticus' thirteenth-century Gesta Danorum. These documents, together with minor German documents and the Icelandic Knýtlinga saga, provide an accurate description of northwestern Slavic religion.[1]

The religions of other Slavic populations are less documented, because writings about the theme were produced late in time after Christianisation, such as the fifteenth-century Polish Chronicle, and contain a lot of sheer inventions. In the times preceding Christianisation, some Greek and Roman chroniclers, such as Procopius and Jordanes in the sixth century, sparsely documented some Slavic concepts and practices. Slavic paganism survived, in more or less pure forms, among the Slovenes along the Soča river up to the 1330s.[9]

Indo-European origins and other influences[edit]

The linguistic unity, and negligible dialectal differentiation, of the Slavs until the end of the first millennium CE, and the lexical uniformity of religious vocabulary, witness a uniformity of early Slavic religion.[9] It has been argued that the essence of early Slavdom was ethnoreligious before being ethnonational; that is to say, belonging to the Slavs was chiefly determined by conforming to certain beliefs and practices rather than by having a certain racial ancestry or being born in a certain place.[10] Ivanov and Toporov identified Slavic religion as an outgrowth of a common Proto-Indo-European religion, sharing strong similarities with other neighbouring Indo-European belief systems such as those of Balts, Thracians, Phrygians and Indo-Iranians.[11] Slavic (and Baltic) religion and mythology is considered more conservative and closer to original Proto-Indo-European religion—and thus precious for the latter's understanding—than other Indo-European traditions, due to the fact that, throughout the history of the Slavs, it remained a popular religion rather than being reworked and sophisticated by intellectual elites as it happened to other Indo-European religious cultures.[12]

The affinity with Proto-Indo-Iranian religion is evident in shared developments, including the elimination of the term for the supreme God of Heaven, *Dyeus, and its substitution by the term for "sky" (Slavic Nebo),[9] the shift of the Indo-European descriptor of heavenly deities (Avestan daeva, Old Church Slavonic div; Proto-Indo-European *deiwos, "celestial", similar to Dyeus) to the designation of evil entities, and the parallel designation of gods by the term meaning both "wealth" and its "giver" (Avestan baga, Slavic bog).[13] Much of the religious vocabulary of the Slavs, including vera (loosely translated as "faith", meaning "radiation of knowledge"), svet ("light"), mir ("peace", "agreement of parts", also meaning "world") and rai ("paradise"), is shared with Iranian.[14]

According to Adrian Ivakhiv, the Indo-European element of Slavic religion may have included what Georges Dumézil studied as the "trifunctional hypothesis", that is to say a threefold conception of the social order, represented by the three castes of priests, warriors and farmers. According to Gimbutas, Slavic religion represented an unmistakable overlapping of Indo-European patriarchal themes and pre-Indo-European—or what she called "Old European"—matrifocal themes. The latter were particularly hardwearing in Slavic religion, represented by the widespread devotion to Mat Syra Zemlya, the "Damp Mother Earth". Rybakov said the continuity and gradual complexification of Slavic religion, which started from devotion to life-giving forces (bereginy), ancestors and the supreme God, Rod ("Generation" itself), and developed into the "high mythology" of the official religion of the early Kievan Rus'.[15]

God and spirits[edit]

As attested by Helmold (c. 1120–1177) in his Chronica Slavorum, the Slavs believed in a single heavenly God begetting all the lesser spirits governing nature, and worshipped it by their means.[18] According to Helmold, "obeying the duties assigned to them, [the deities] have sprung from his [the supreme God's] blood and enjoy distinction in proportion to their nearness to the god of the gods".[14] According to Rybakov's studies, wheel symbols such as the "thunder marks" (gromovoi znak) and the "six-petaled rose inside a circle" (e.g. ![]() ), which are so common in Slavic folk crafts, and which were still carved on edges and peaks of roofs in northern Russia in the nineteenth century, were symbols of the supreme life-giver Rod.[19] Before its conceptualisation as Rod as studied by Rybakov, this supreme God was known as Deivos (cognate with Sanskrit Deva, Latin Deus, Old High German Ziu and Lithuanian Dievas).[18] The Slavs believed that from this God proceeded a cosmic duality, represented by Belobog ("White God") and Chernobog ("Black God", also named Tiarnoglofi, "Black Head/Mind"),[18] representing the root of all the heavenly-masculine and the earthly-feminine deities, or the waxing light and waning light gods, respectively.[20] In both categories, deities might be either Razi, "rede-givers", or Zirnitra, "wizards".[21]

), which are so common in Slavic folk crafts, and which were still carved on edges and peaks of roofs in northern Russia in the nineteenth century, were symbols of the supreme life-giver Rod.[19] Before its conceptualisation as Rod as studied by Rybakov, this supreme God was known as Deivos (cognate with Sanskrit Deva, Latin Deus, Old High German Ziu and Lithuanian Dievas).[18] The Slavs believed that from this God proceeded a cosmic duality, represented by Belobog ("White God") and Chernobog ("Black God", also named Tiarnoglofi, "Black Head/Mind"),[18] representing the root of all the heavenly-masculine and the earthly-feminine deities, or the waxing light and waning light gods, respectively.[20] In both categories, deities might be either Razi, "rede-givers", or Zirnitra, "wizards".[21]

The Slavs perceived the world as enlivened by a variety of spirits, which they represented as persons and worshipped. These spirits included those of waters (mavka and rusalka), forests (lisovyk), fields (polyovyk), those of households (domovyk), those of illnesses, luck and human ancestors.[22] For instance, Leshy is an important woodland spirit, believed to distribute food assigning preys to hunters, later regarded as a god of flocks and herds, and still worshipped in this function in early twentieth-century Russia. Many gods were regarded by kins (rod or pleme) as their ancestors, and the idea of ancestrality was so important that Slavic religion may be epitomised as a "manism" (i.e. worship of ancestors), though the Slavs did not keep genealogical records.[18] The Slavs also worshipped star-gods, including the moon (Russian: Mesyats) and the sun (Solntse), the former regarded as male and the latter as female. The moon-god was particularly important, regarded as the dispenser of abundance and health, worshipped through round dances, and in some traditions considered the progenitor of mankind. The belief in the moon-god was still very much alive in the nineteenth century, and peasants in the Ukrainian Carpathians openly affirm that the moon is their god.[18]

There was an evident continuity between the beliefs of the East Slavs, West Slavs and South Slavs. They shared the same traditional deities, as attested, for instance, by the worship of Zuarasiz among the West Slavs, corresponding to Svarožič among the East Slavs.[23] All the bright male deities were regarded as the hypostases, forms or phases in the year, of the active, masculine divine force personified by Perun ("Thunder"). His name, from the Indo-European root *per or *perkw ("to strike", "splinter"), signified both the splintering thunder and the splintered tree (especially the oak; the Latin name of this tree, quercus, comes from the same root), regarded as symbols of the irradiation of the force. This root also gave rise to the Vedic Parjanya, the Baltic Perkunas, the Albanian Perëndi (now denoting "God" and "sky"), the Germanic Fjörgynn and the Greek Keraunós ("thunderbolt", rhymic form of *Peraunós, used as an epithet of Zeus).[24] Prĕgyni or peregyni, in modern Russian folklore rendered bregynja or beregynja (from breg, bereg, meaning "shore") and reinterpreted as female water spirits, were rather—as attested by chronicles and highlighted by the root *per—spirits of trees and rivers related to Perun.[25] Slavic traditions preserved very ancient Indo-European elements and intermingled with those of neighbouring Indo-European peoples. An exemplary case are the South Slavic still-living rain rituals of the couple Perun–Perperuna, Lord and Lady Thunder, shared with the neighbouring Albanians, Greeks and Arumanians, corresponding to the Germanic Fjörgynn–Fjörgyn, the Lithuanian Perkūnas–Perkūna, and finding similarities in the Vedic hymns to Parjanya.[26]

The West Slavs, especially those of the Baltic, worshipped prominently Svetovid ("Lord of Power"), while the East Slavs worshipped prominently Perun himself, especially after Vladimir's 970s–980s reforms.[19] The various spirits were believed to manifest in certain places, which were revered as numinous and holy; they included springs, rivers, groves, rounded tops of hills and flat cliffs overlooking rivers. Calendrical rituals were attuned with the spirits, which were believed to have periods of waxing and waning throughout the year, determining the agrarian fertility cycle.[22]

Cosmology, iconography, temples and rites[edit]

The cosmology of ancient Slavic religion, which is preserved in contemporary Slavic folk religion, is visualised as a three-tiered vertical structure, or "world tree", as common in other Indo-European religions. At the top there is the heavenly plane, symbolised by birds, the sun and the moon; the middle plane is that of earthly humanity, symbolised by bees and men; at the bottom of the structure there is the netherworld, symbolised by snakes and beavers, and by the chthonic god Veles. The Zbruch Idol (which was identified at first as a representation of Svetovid[27]), found in western Ukraine, represents this theo-cosmology: the three-layered effigy of the four major deities—Perun, Dazhbog, Mokosh and Lada—is constituted by a top level with four figures representing them, facing the four cardinal directions; a middle level with representations of a human ritual community (khorovod); and a bottom level with the representation of a three-headed chthonic god, Veles, who sustains the entire structure.[28]

The scholar Jiří Dynda studied the figure of Triglav (literally the "Three-Headed One") and Svetovid, which are widely attested in archaeological testimonies, as the respectively three-headed and four-headed representations of the same axis mundi, of the same supreme God.[29] Triglav itself was connected to the symbols of the tree and the mountain, which are other common symbols of the axis mundi, and in this quality he was a summus deus (a sum of all things), as recorded by Ebbo (c. 775–851).[30] Triglav represents the vertical interconnection of the three worlds, reflected by the three social functions studied by Dumézil: sacerdotal, martial and economic.[31] Ebbo himself documented that the Triglav was seen as embodying the connection and mediation between Heaven, Earth and the underworld.[32] Adam of Bremen (c. 1040s–1080s) described the Triglav of Wolin as Neptunus triplicis naturae (that is to say "Neptune of the three natures/generations") attesting the colours that were associated to the three worlds, also studied by Karel Jaromír Erben (1811–1870): white for Heaven, green for Earth and black for the underworld.[31] It also represents the three dimensions of time, mythologically rendered in the figure of a three-threaded rope. Triglav is Perun in the heavenly plane, Svetovid in the centre from which the horizontal four directions unfold, and Veles the psychopomp in the underworld.[33] Svetovid is interpreted by Dynda as the incarnation of the axis mundi in the four dimensions of space.[34] Helmold defined Svetovid as deus deorum ("god of all gods").[35]

Besides Triglav and Svetovid, other deities were represented with many heads. This is attested by chroniclers who wrote about West Slavs, including Saxo Grammaticus (c. 1160–1220). According to him, Rugievit in Charenza was represented with seven faces, which converged at the top in a single crown.[36] These three-, four- or many-headed images, wooden or carved in stone,[28] some covered in metal,[18] which held drinking horns and were decorated with solar symbols and horses, were kept in temples, of which numerous archaeological remains have been found. They were built on upraised platforms, frequently on hills,[28] but also at the confluences of rivers.[18] The biographers of Otto of Bamberg (1060/1061–1139) inform that these temples were known as continae, "dwellings", among West Slavs, testifying that they were regarded as the houses of the gods.[36] They were wooden buildings with an inner cell with the god's statue, located in wider walled enclosures or fortifications; such fortifications might contain up to four continae.[18] Different continae were owned by different kins, and used for the ritual banquets in honour of their own ancestor-gods. These ritual banquets are known variously, across Slavic countries, as bratchina (from brat, "brother"), mol'ba ("entreaty", "supplication") and kanun (short religious service) in Russia; slava ("glorification") in Serbia; sobor ("assembly") and kurban ("sacrifice") in Bulgaria. With Christianisation, the ancestor-gods were replaced with Christian patron saints.[18]

There were also holy places with no buildings, where the deity was believed to manifest in nature itself; such locations were characterised by the combined presence of trees and springs, according to the description of one such sites in Szczecin by Otto of Bamberg. A shrine of the same type in Kobarid, contemporary Slovenia, was stamped out in a "crusade" as recently as 1331.[37] Usually, common people were not allowed into the presence of the images of their gods, the sight of which was a privilege of the priests. Many of these images were seen and described only in the moment of their violent destruction at the hands of the Christian missionaries.[3] The priests (volkhvs), who kept the temples and led rituals and festivals, enjoyed a great degree of prestige; they received tributes and shares of military booties by the kins' chiefs.[18]

History[edit]

Kievan Rus' official religion and popular cults[edit]

In 980 CE,[38] in Kievan Rus', led by the Great Prince Vladimir, there was an attempt to unify the various beliefs and priestly practices of Slavic religion in order to bind together the Slavic peoples in the growing centralised state. Vladimir canonised a number of deities, to whom he erected a temple on the hills of the capital Kiev.[39] These deities, recorded in the Primary Chronicle, were five: Perun, Xors Dazhbog,[40] Stribog, Simargl and Mokosh.[41] Various other deities were worshipped by the common people, notably Veles who had a temple in the merchant's district of Podil of the capital itself.[42] According to scholars, Vladimir's project consisted in a number of reforms that he had already started by the 970s, and which were aimed at preserving the traditions of the kins and making Kiev the spiritual centre of East Slavdom.[43]

Perun was the god of thunder, law and war, symbolised by the oak and the mallet (or throwing stones), and identified with the Baltic Perkunas, the Germanic Thor and the Vedic Indra among others; his cult was practised not so much by commoners but mainly by the aristocracy. Veles was the god of horned livestock (Skotibog), of wealth and of the underworld. Perun and Veles symbolised an oppositional and yet complementary duality similar to that of the Vedic Mitra and Varuna, an eternal struggle between heavenly and chthonic forces. Roman Jakobson himself identified Veles as the Vedic Varuna, god of oaths and of the world order. This belief in a cosmic duality was likely the reason that led to the exclusion of Veles from Vladimir's official temple in Kiev.[44] Xors Dazhbog ("Radiant Giving-God") was the god of the life-bringing power of the sun. Stribog was identified by E. G. Kagarov as the god of wind, storm and dissension.[41] Mokosh, the only female deity in Vladimir's pantheon, is interpreted as meaning the "Wet" or "Moist" by Jakobson, identifying her with the Mat Syra Zemlya ("Damp Mother Earth") of later folk religion.[45] According to scholars, Xors Dazhbog, Simargl and Stribog represent the unmistakable Indo-Iranian (Scythian and Sarmatian) component of Slavic religion.[42]

According to Ivanits, written sources from the Middle Ages "leave no doubt whatsoever" that the common Slavic peoples continued to worship their indigenous deities and hold their rituals for centuries after Kievan Rus' official baptism into Christianity, and the lower clergy of the newly formed Orthodox Christian church often joined the celebrations.[41] The high clergy repeatedly condemned, through official admonitions, the worship of Rod and the Rozhanitsy ("God and the Goddesses", or "Generation and the generatrixes") with offerings of bread, porridge, cheese and mead. Scholars of Russian religion define Rod as the "general power of birth and reproduction" and the Rozhanitsy as the "mistresses of individual destiny". Kagarov identified the later Domovoi, the god of the household and kinship ancestry, as a specific manifestation of Rod. Other gods attested in medieval documents remain largely mysterious, for instance Lada and her sons Lel and Polel, who are often identified by scholars with the Greek gods Leda or Leto and her twin sons Castor and Pollux. Other figures who in medieval documents are often presented as deities, such as Kupala and Koliada, were rather the personifications of the spirits of agrarian holidays.[45]

Christianisation of the East Slavs[edit]

Vladimir's baptism, popular resistance and syncretism[edit]

In 988, Vladimir of Kievan Rus' rejected Slavic religion and he and his subjects were officially baptised into the Eastern Orthodox Church, then the state religion of the Byzantine Empire. According to legend, Vladimir sent delegates to foreign states to determine what was the most convincing religion to be adopted by Kiev.[2] Joyfulness and beauty were the primary characteristics of pre-Christian Slavic ceremonies, and the delegates sought for something capable of matching these qualities. They were crestfallen by the Islamic religion of Volga Bulgaria, where they found "no joy ... but sorrow and great stench", and by Western Christianity (then the Catholic Church) where they found "many worship services, but nowhere ... beauty".[48] Those who visited Constantinople were instead impressed by the arts and rituals of Byzantine Christianity.[2] According to the Primary Chronicle, after the choice was made Vladimir commanded that the Slavic temple on the Kievan hills be destroyed and the effigies of the gods be burned or thrown into the Dnieper. Slavic temples were destroyed throughout the lands of Kievan Rus' and Christian churches were built in their places.[2]

According to Ivakhiv, Christianisation was stronger in what is today western and central Ukraine, lands close to the capital Kiev. Slavic religion persisted, however, especially in northernmost regions of Slavic settlement, in what is today the central part of European Russia, such as the areas of Novgorod, Suzdal and Belozersk. In the core regions of Christianisation themselves the common population remained attached to the volkhvs, the priests, who periodically, over centuries, led popular rebellions against the central power and the Christian church. Christianisation was a very slow process among the Slavs, and the official Christian church adopted a policy of co-optation of pre-Christian elements into Slavic Christianity. Christian saints were identified with Slavic gods—for instance, the figure of Perun was overlapped with that of Saint Elias, Veles was identified with Saint Blasius, and Yarilo became Saint George—and Christian festivals were set at the same dates as pagan ones.[2]

Another feature of early Slavic Christianity was the strong influence of apocryphal literature, which became evident by the thirteenth century with the rise of Bogomilism among the South Slavs. South Slavic Bogomilism produced a large amount of apocryphal texts and their teachings later penetrated into Russia, and would have influenced later Slavic folk religion. Bernshtam tells of a "flood" of apocryphal literature in eleventh- to fifteenth-century Russia, which might not be controlled by the still-weak Russian Orthodox Church.[49]

Continuity of Slavic religion in Russia up to the 15th century[edit]

Scholars have highlighted how the "conversion of Rus" took place no more than eight years after Vlardimir's reform of Slavic religion in 980; according to them Christianity in general did not have "any deep influence ... in the formation of the ideology, culture and social psychology of archaic societies" and the introduction of Christianity in Kiev "did not bring about a radical change in the consciousness of the society during the entire course of early Russian history". It was portrayed as a mass and conscious conversion only by half a century later, by the scribes of the Christian establishment.[38] According to scholars, the replacement of Slavic temples with Christian churches and the "baptism of Rus" has to be understood in continuity with the foregoing chain of reforms of Slavic religion launched by Vladimir, rather than as a breaking point.[50]

V. G. Vlasov quotes the respected scholar of Slavic religion E. V. Anichkov, who, regarding Russia's Christianisation, said:[51]

Christianization of the countryside was the work, not of the eleventh and twelfth, but of the fifteenth and sixteenth or even seventeenth century.

According to Vlasov the ritual of baptism and mass conversion undergone by Vladimir in 988 was never repeated in the centuries to follow, and mastery of Christian teachings was never accomplished on the popular level even by the start of the twentieth century. According to him, a nominal, superficial identification with Christianity was possible with the superimposition of a Christianised agrarian calendar ("Christian–Easter–Whitsunday") over the indigenous complex of festivals, "Koliada–Yarilo–Kupala". The analysis of the Christianised agrarian and ritual calendar, combined with data from popular astronomy, leads to determine that the Julian calendar associated with the Orthodox Church was adopted by Russian peasants between the sixteenth and seventeenth century. It was by this period that much of the Russian population became officially part of the Orthodox Church and therefore nominally Christians.[52] This occurred as an effect of a broader complex of phenomena which Russia underwent by the fifteenth century, that is to say radical changes towards a centralisation of state power, which involved urbanisation, bureaucratisation and the consolidation of serfdom of the peasantry.[53]

That the vast majority of the Russian population was not Christian back in the fifteenth century would be proven by archaeology: according to Vlasov, mound (kurgan) burials, which do not reflect Christian norms, were "a universal phenomenon in Russia up to the fifteenth century", and persisted into the 1530s.[54] Moreover, chronicles from that period, such as the Pskov Chronicle, and archaeological data collected by N. M. Nikolsky, testify that back in the fifteenth century there were still "no rural churches for the general use of the populace; churches existed only at the courts of boyars and princes".[55] It was only by the sixteenth century that the Russian Orthodox Church grew as a powerful, centralising institution taking the Catholic Church of Rome as a model, and the distinctiveness of a Slavic folk religion became evident. The church condemned "heresies" and tried to eradicate the "false half-pagan" folk religion of the common people, but these measures coming from the centres of church power were largely ineffective, and on the local level creative syntheses of folk religious rituals and holidays continued to thrive.[56]

Sunwise Slavic religion, withershins Christianity, and Old Belief[edit]

When the incorporation of the Russian population into Christianity became substantial in the middle of the sixteenth century, the Russian Orthodox Church absorbed further elements of pre-Christian and popular tradition and underwent a transformation of its architecture, with the adoption of the hipped roof which was traditionally associated to pre-Christian Slavic temples. The most significant change was however the adoption of the sunwise direction in Christian ritual procession.[57]

Christianity is characterised by withershins ritual movement, that is to say movement against the course of the sun. This was also the case in Slavic Christianity before the sixteenth century. Sunwise movements are instead characteristic of Slavic religion, evident in the khorovod, ritual circle-dance, which magically favours the development of things. Withershins movement was employed in popular rituals, too, though only in those occasions when it was considered worthwhile to act against the course of nature, in order to alter the state of affairs.[58]

When Patriarch Nikon of Moscow launched his reform of the Orthodox Church in 1656, he restored the withershins ritual movement. This was among the changes that led to a schism (raskol) within Russian Orthodoxy, between those who accepted the reforms and the Old Believers, who preserved instead the "ancient piety" derived from indigenous Slavic religion.[58] A large number of Russians and ethnic minorities converted to the movement of the Old Believers, in the broadest meaning of the term—including a variety of folk religions—pointed out by Bernshtam, and these Old Believers were a significant part of the settlers of broader European Russia and Siberia throughout the second half of the seventeenth century, which saw the expansion of the Russian state in these regions. Old Believers were distinguished by their cohesion, literacy and initiative, and constantly-emerging new religious sects tended to identify themselves with the movement. This posed a great hitch to the Russian Orthodox Church's project of thorough Christianisation of the masses.[59] Veletskaya highlighted how the Old Believers have preserved Indo-European and early Slavic ideas and practices such as the veneration of fire as a channel to the divine world, the symbolism of the colour red, the search for a "glorious death", and more in general the holistic vision of a divine cosmos.[60]

Christianisation of the West Slavs[edit]

In the opinion of Norman Davies,[61] the Christianization of Poland through the Czech–Polish alliance represented a conscious choice on the part of Polish rulers to ally themselves with the Czech state rather than the German one. The Moravian cultural influence played a significant role in the spread of Christianity onto the Polish lands and the subsequent adoption of that religion. Christianity arrived around the late 9th century, most likely around the time when the Vistulan tribe encountered the Christian rite in dealings with their neighbours, the Great Moravia (Bohemian) state. The "Baptism of Poland" refers to the ceremony when the first ruler of the Polish state, Mieszko I and much of his court, converted to the Christianity on the Holy Saturday of 14 April 966.[62]

In the eleventh century, Slavic pagan culture was "still in full working order" among the West Slavs. Christianity faced popular opposition, including an uprising in the 1030s (particularly intense in the years of 1035–1037).[63] By the twelfth century, however, under the pressure of Germanisation, Catholicism was forcefully imposed through the Northern Crusades and temples and images of Slavic religion were violently destroyed. West Slavic populations stood out vigorously against Christianisation.[3] One of the most famous instances of popular resistance occurred at the temple-stronghold of Svetovid at Cape Arkona, in Rugia.[2] The temple at Arkona had a squared groundplan, with an inner hall sustained by four pillars which contained Svetovid's statue.[64] The latter had four heads, represented beardless and cleanshaven after the Rugian fashion. In the right hand, the statue held a horn of precious metal, which was used for divination during the yearly great festival of the god.[65] In 1168, Arkona surrendered to the Danish troops of King Valdemar I, and the bishop Absalon led the destruction of the temple of Svetovid.[3]

Slavic folk religion[edit]

Ethnography in late-nineteenth-century Ukraine documented a "thorough synthesis of pagan and Christian elements" in Slavic folk religion, a system often called "double belief" (Russian: dvoeverie, Ukrainian: dvovirya).[22] According to Bernshtam, dvoeverie is still used to this day in scholarly works to define Slavic folk religion, which is seen by certain scholars as having preserved much of pre-Christian Slavic religion, "poorly and transparently" covered by a Christianity that may be easily "stripped away" to reveal more or less "pure" patterns of the original faith.[66] Since the collapse of the Soviet Union there has been a new wave of scholarly debate on the subjects of Slavic folk religion and dvoeverie. A. E. Musin, an academic and deacon of the Russian Orthodox Church published an article about the "problem of double belief" as recently as 1991. In this article he divides scholars between those who say that Russian Orthodoxy adapted to entrenched indigenous faith, continuing the Soviet idea of an "undefeated paganism", and those who say that Russian Orthodoxy is an out-and-out syncretic religion.[67] Bernshtam challenges dualistic notions of dvoeverie and proposes to interpret broader Slavic religiosity as a mnogoverie ("multifaith") continuum, in which a higher layer of Orthodox Christian officialdom is alternated with a variety of "Old Beliefs" among the various strata of the population.[68]

According to Ivanits, nineteenth- and twentieth-century Slavic folk religion's central concern was fertility, propitiated with rites celebrating death and resurrection. Scholars of Slavic religion who focused on nineteenth-century folk religion were often led to mistakes such as the interpretation of Rod and Rozhanitsy as figures of a merely ancestral cult; however in medieval documents Rod is equated with the ancient Egyptian god Osiris, representing a broader concept of natural generativity.[69] Belief in the holiness of Mat Syra Zemlya ("Damp Mother Earth") is another feature that has persisted into modern Slavic folk religion; up to the twentieth century, Russian peasants practised a variety of rituals devoted to her and confessed their sins to her in the absence of a priest. Ivanits also reports that in the region of Vladimir old people practised a ritual asking Earth's forgiveness prior to their death. A number of scholars attributed the Russians' particular devotion to the Theotokos, the "Mother of God", to this still powerful pre-Christian substratum of devotion to a great mother goddess.[69]

Ivanits attributes the tenacity of synthetic Slavic folk religion to an exceptionality of Slavs and of Russia in particular, compared to other European countries; "the Russian case is extreme", she says, because Russia—especially the vastity of rural Russia—neither lived the intellectual upheavals of the Renaissance, nor the Reformation, nor the Age of Enlightenment, which severely weakened folk spirituality in the rest of Europe.[70]

Slavic folk religious festivals and rites reflect the times of the ancient pagan calendar. For instance, the Christmas period is marked by the rites of Koliada, characterised by the element of fire, processions and ritual drama, offerings of food and drink to the ancestors. Spring and summer rites are characterised by fire- and water-related imagery spinning umbe the figures of the gods Yarilo, Kupala and Marzanna. The switching of seasonal spirits is celebrated through the interaction of effigies of these spirits and the elements which symbolise the coming season; for instance by burning, drowning or setting the effigies onto water, and the "rolling of burning wheels of straw down into rivers".[22]

Modern Rodnovery[edit]

| Part of a series on |

| Slavic Native Faith |

|---|

|

|

Denominations Not strictly related ones: |

|

Spread |

Since the early twentieth century there has been a reinvention and reinstitutionalisation of "Slavic religion" in the so-called movement of "Rodnovery", literally "Slavic Native Faith". The movement draws from ancient Slavic folk religion, often combining it with philosophical underpinnings taken from other religions, chiefly Hinduism.[71]:26 Some Rodnover groups focus almost exclusively on folk religions and the worship of gods at the right times of the year, while others have developed a scriptural core, represented by writings purported to be centuries-old documents such as the Book of Veles; writings which elaborate powerful national mythologemes such as the Maha Vira of Sylenkoism;[72] and esoteric writings such as the Slavo-Aryan Vedas of Ynglism.[71]:50

Reconstructed calendar of celebrations[edit]

Linda J. Ivanits reconstructed a basic calendar of the celebrations of the most important Slavic gods among East Slavs, based on Boris Rybakov's studies on ancient agricultural calendars, especially a fourth-century one from an area around Kiev.[19]

| Festival | Date (Julian or Gregorian) | Deity celebrated | Overlapped Christian festival or figure |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yuletide (Koliada) | Winter solstice | Rod – first half Veles – second half |

Christmas, Baptism of the Lord, Epiphany |

| Shrovetide (Komoeditsa) | Spring equinox | Veles | N/A |

| Day of Young Shoots | May 2 | N/A | Saints Boris and Gleb |

| Semik | June 4 | Yarilo | N/A |

| Rusalnaya Week | June 17–23 | Simargl | Trinity Sunday |

| Kupala Night / Kupalo | June 24 | N/A | Saint John the Baptist |

| Festival of Perun | July 20 | Rod—Perun | Saint Elijah |

| Harvest festivals | July 24 / September 9 | Rodzanica—Rodzanicy | Feast of the Transfiguration (August 6) / Birthday of the Mother of God (September 8) |

| Festival of Mokosh | October 28 | Mokosh | Saint Paraskeva's Friday |

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

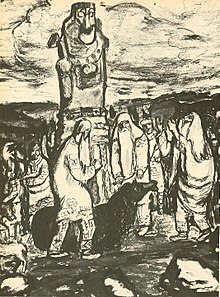

- ^ Anna Dvořák, in the upper right section of The Celebration of Svantovit, identifies a group of priests. The figure of a priest with his arms stretched out prays for the future of the Slavs, both in times of peace (represented by the young man to his left) and in times of war (the man with a sword to the priest's right).[6]

References[edit]

Citations[edit]

- ^ a b c d e Rudy 1985, p. 3.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Ivakhiv 2005, p. 214.

- ^ a b c d e Pettazzoni 1967, p. 154.

- ^ Radovanovič, Bojana (2013). "The Typology of Slavic Settlements in Central Europe in the Middle Ages". In Rudić, Srđan (ed.). The World of the Slavs: Studies of the East, West and South Slavs: Civitas, Oppidas, Villas and Archeological Evidence (7th to 11th Centuries CE). Belgrade, Serbia: Historical Institute (Istorijski institut). ISBN 9788677431044. p. 367.

- ^ Ivanits 1989, pp. 15–16; Rudy 1985, p. 9; Gasparini 2013.

- ^ Dvořák, "The Slav Epic". In: Brabcová-Orlíková, Jana; Dvořák, Anna. Alphonse Mucha—The Spirit of Art Nouveau. Art Services International, 1998. ISBN 0300074190. p. 107.

- ^ Ivakhiv 2005, p. 211.

- ^ Ivanits 1989, p. 16.

- ^ a b c Rudy 1985, p. 4.

- ^ Gąssowski, Jerzy (2002). "Early Slavs: Nation or Religion?". In Pohl, Walter; Diesenberger, Maximilian (eds.). Integration und Herrschaft: ethnische Identitäten und soziale Organisation im Frühmittelalter. Wien: Austrian Academy of Sciences Press. ISBN 9783700130406.

- ^ Ivakhiv 2005, p. 211; Rudy 1985, p. 4.

- ^ Rudy 1985, p. 32.

- ^ Rudy 1985, pp. 4–5, 14–15.

- ^ a b Rudy 1985, p. 5.

- ^ Ivakhiv 2005, pp. 211–212.

- ^ Creuzer & Mone 1822, p. 197.

- ^ Hanuš 1842, p. 182.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Gasparini 2013.

- ^ a b c d Ivanits 1989, p. 17.

- ^ Hanuš 1842, pp. 151–183.

- ^ Creuzer & Mone 1822, pp. 195–197.

- ^ a b c d Ivakhiv 2005, p. 212.

- ^ Pettazzoni 1967, p. 155.

- ^ Rudy 1985, pp. 5–6, 17–21.

- ^ Rudy 1985, pp. 20–21.

- ^ Rudy 1985, pp. 21–22.

- ^ Dynda 2014, p. 62.

- ^ a b c Ivakhiv 2005, p. 213.

- ^ Dynda 2014, passim.

- ^ Dynda 2014, p. 64.

- ^ a b Dynda 2014, p. 63.

- ^ Dynda 2014, p. 60.

- ^ Dynda 2014, pp. 74–75.

- ^ Dynda 2014, p. 75.

- ^ Dynda 2014, p. 59, note 9.

- ^ a b Pettazzoni 1967, p. 156.

- ^ Pettazzoni 1967, pp. 156–157.

- ^ a b Froianov, Dvornichenko & Krivosheev 1992, p. 3.

- ^ Ivakhiv 2005, pp. 213–214.

- ^ Kutarev, O. V. (2016). "Slavic Dažbog as the Development of the Indo-European God of the Shining Sky (Dyeu Ph2ter)". Philosophy and Culture. 1: 126–141. doi:10.7256/1999-2793.2016.1.17386.

- ^ a b c Ivanits 1989, p. 13.

- ^ a b Ivanits 1989, p. 13; Ivakhiv 2005, p. 214.

- ^ Froianov, Dvornichenko & Krivosheev 1992, p. 4.

- ^ Ivanits 1989, pp. 13–14; Ivakhiv 2005, p. 214.

- ^ a b Ivanits 1989, p. 14.

- ^ Rouček, Joseph Slabey, ed. (1949). "Ognyena Maria". Slavonic Encyclopedia. New York: Philosophical Library. p. 905

- ^ Ivanits 1989, pp. 15, 16.

- ^ Froianov, Dvornichenko & Krivosheev 1992, p. 6.

- ^ Bernshtam 1992, p. 39.

- ^ Froianov, Dvornichenko & Krivosheev 1992, p. 10.

- ^ Vlasov 1992, p. 16.

- ^ Vlasov 1992, p. 17.

- ^ Vlasov 1992, p. 18.

- ^ Vlasov 1992, pp. 18–19.

- ^ Vlasov 1992, p. 19.

- ^ Vlasov 1992, pp. 19–20; Bernshtam 1992, p. 40.

- ^ Vlasov 1992, p. 24.

- ^ a b Vlasov 1992, p. 25.

- ^ Bernshtam 1992, p. 40.

- ^ Veletskaya 1992, passim.

- ^ Davies, Norman (2005). God's playground : a history of Poland : in two volumes (Revised ed.). New York. pp. 53. ISBN 0231128169. OCLC 57754186.

- ^ Kłoczowski, Jerzy (2000). A history of Polish Christianity. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. 10–13. ISBN 0521364299. OCLC 42812968.

- ^ Norman, Davies (2005). God's playground : a history of Poland : in two volumes (Revised ed.). New York: Columbia University Press. pp. 57. ISBN 0231128169. OCLC 57754186.

- ^ Pettazzoni 1967, p. 158.

- ^ Pettazzoni 1967, p. 98.

- ^ Bernshtam 1992, p. 35.

- ^ Rock 2007, p. 110.

- ^ Bernshtam 1992, p. 44.

- ^ a b Ivanits 1989, p. 15.

- ^ Ivanits 1989, p. 3.

- ^ a b Aitamurto, Kaarina (2016). Paganism, Traditionalism, Nationalism: Narratives of Russian Rodnoverie. London and New York: Routledge. ISBN 9781472460271.

- ^ Ivakhiv 2005, pp. 217 ff.

Sources[edit]

- Creuzer, Georg Friedrich; Mone, Franz Joseph (1822). Geschichte des Heidentums im nördlichen Europa. Symbolik und Mythologie der alten Völker (in German). 1. Georg Olms Verlag. ISBN 9783487402741.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bernshtam, T. A. (1992). "Russian Folk Culture and Folk Religion". In Balzer Marjorie Mandelstam; Radzai Ronald (eds.). Russian Traditional Culture: Religion, Gender and Customary Law. Routledge. pp. 34–47. ISBN 9781563240393.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dynda, Jiří (2014). "The Three-Headed One at the Crossroad: A Comparative Study of the Slavic God Triglav" (PDF). Studia mythologica Slavica. Institute of Slovenian Ethnology. 17: 57–82. doi:10.3986/sms.v17i0.1495. ISSN 1408-6271. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 July 2017.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Froianov, I. Ia.; Dvornichenko, A. Iu.; Krivosheev, Iu. V. (1992). "The Introduction of Christianity in Russia and the Pagan Traditions". In Balzer Marjorie Mandelstam; Radzai Ronald (eds.). Russian Traditional Culture: Religion, Gender and Customary Law. Routledge. pp. 3–15. ISBN 9781563240393.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gasparini, Evel (2013). "Slavic religion". Encyclopædia Britannica.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hanuš, Ignác Jan (1842). Die Wissenschaft des Slawischen Mythus im weitesten, den altpreussisch-lithauischen Mythus mitumfassenden Sinne. Nach Quellen bearbeitet, sammt der Literatur der slawisch-preussisch-lithauischen Archäologie und Mythologie (in German). J. Millikowski.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ivakhiv, Adrian (2005). "The Revival of Ukrainian Native Faith". In Michael F. Strmiska (ed.). Modern Paganism in World Cultures: Comparative Perspectives. Santa Barbara: ABC-Clio. pp. 209–239. ISBN 9781851096084.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ivanits, Linda J. (1989). Russian Folk Belief. M. E. Sharpe. ISBN 9780765630889.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pettazzoni, Raffaele (1967). "West Slav Paganism". Essays on the History of Religions. Brill Archive.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rudy, Stephen (1985). Contributions to Comparative Mythology: Studies in Linguistics and Philology, 1972–1982. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 9783110855463.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rock, Stella (2007). Popular Religion in Russia: 'Double Belief' and the Making of an Academic Myth. Routledge. ISBN 9781134369782.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Veletskaya, N. N. (1992). "Forms of Transformation of Pagan Symbolism in the Old Believer Tradition". In Balzer Marjorie Mandelstam and Radzai Ronald (ed.). Russian Traditional Culture: Religion, Gender and Customary Law. Routledge. pp. 48–60. ISBN 9781563240393.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Vlasov, V. G. (1992). "The Christianization of Russian Peasants". In Balzer Marjorie Mandelstam; Radzai Ronald (eds.). Russian Traditional Culture: Religion, Gender and Customary Law. Routledge. pp. 16–33. ISBN 9781563240393.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading[edit]

- Gimbutas, Marija (1971). The Slavs. New York: Preager Publishers.

- Ingemann, B. S. (1824). Grundtræk til En Nord-Slavisk og Vendisk Gudelære. Copenhagen.

- Rybakov, Boris (1981). Iazychestvo drevnykh slavian [Paganism of the Ancient Slavs]. Moscow.

- Rybakov, Boris (1987). Iazychestvo drevnei Rusi [Paganism of Ancient Rus]. Moscow.

- Patrice Lajoye (ed.), New researches on the religion and mythology of the Pagan Slavs, Lisieux, Lingva, 2019

External links[edit]

Media related to Slavic paganism at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Slavic paganism at Wikimedia Commons- Studia mythologica Slavica, journal of the Institute of Slovenian Ethnology.

- (in Slovak) a book about old Slavic mythology - HOSTINSKÝ, Peter Záboj. Stará vieronauka slovenská : Vek 1:kniha 1. [1. vyd.] Pešť: Minerva, 1871. 122 p. - available online at ULB's Digital Library