Territories of the United States

It has been suggested that this article be merged into U.S. territory. (Discuss) Proposed since February 2020. |

Territories of the United States | |

|---|---|

Incorporated, unorganized territory

Unincorporated territory with Commonwealth status

Unincorporated, organized territory

Unincorporated, unorganized territory | |

| Largest settlement | San Juan, Puerto Rico |

| Languages | English, Spanish, Chamorro, Carolinian, Samoan |

| Demonym(s) | American |

| Territories | |

| Leaders | |

| Donald Trump | |

| List of current territorial governors | |

| Area | |

• Total | 22,294.19 km2 (8,607.83 sq mi) |

| Population | |

• Estimate | 4,100,954 in 2010[1] 3,672,195 in 2018[2][3][4][5][6][note 1] |

| Currency | United States dollar |

| Date format | mm/dd/yyyy (AD) |

| |

| Administrative divisions of the United States |

|---|

| First level |

|

|

| Second level |

|

| Third level |

|

|

| Fourth level |

| Other areas |

|

|

Territories of the United States are sub-national administrative divisions overseen by the United States government. The various U.S. territories differ from the U.S. states and Native American tribes in that they are not sovereign entities. (Each state has individual sovereignty by which it delegates powers to the federal government; each federally recognized tribe possesses limited tribal sovereignty as a "dependent sovereign nation".)[8][note 2] They are classified by incorporation and whether they have an "organized" government through an organic act passed by Congress.[9] All U.S. territories are part of the United States (because they are under U.S. sovereignty),[10] but the unincorporated territories are not considered to be integral parts of the United States,[11] and the Constitution of the United States applies only partially in those territories.[12][13][9][14]

The U.S. currently has fourteen[12][15] territories in the Caribbean Sea and the Pacific Ocean.[note 3][note 4] Five territories (American Samoa, Guam, the Northern Mariana Islands, Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands) are permanently inhabited, unincorporated territories; the other nine are small islands, atolls and reefs with no native (or permanent) population. Of the nine, only one is classified as an incorporated territory (Palmyra Atoll). Two additional territories (Bajo Nuevo Bank and Serranilla Bank) are claimed by the United States but administered by Colombia.[13][17][18] Historically, territories were created to administer newly acquired land, and most eventually attained statehood.[19][20] Others, such as the Philippines, Micronesia, the Marshall Islands and Palau, later became independent.[note 5]

Many organized incorporated territories of the United States existed from 1789 to 1959. The first were the Northwest and Southwest territories and the last were the Alaska and Hawaii territories. Thirty-one territories (or parts of territories) became states. In the process, some less-populous areas of a territory were orphaned from it after a statehood referendum. When a portion of the Missouri Territory became the state of Missouri, the remainder of the territory (the present-day states of Iowa, Nebraska, South Dakota and North Dakota, most of Kansas, Wyoming, and Montana, and parts of Colorado and Minnesota) became an unorganized territory.[21]

Politically and economically, the territories are underdeveloped. People in U.S. territories cannot vote for the President of the United States, and they do not have full representation in the U.S. Congress.[13] Territorial telecommunications and other infrastructure is generally inferior to that of the continental United States and Hawaii, and American Samoa's Internet speed was found to be slower than several Eastern European countries.[22] Poverty rates are higher in the territories than in the states.[23][24]

Legal status of territories[edit]

The U.S. has had territories since its beginning.[25] According to federal law, the term "United States" (used in a geographical sense) means "the continental United States, Hawaii, Puerto Rico, Guam, and the United States Virgin Islands".[26] Since 1986, the Northern Mariana Islands have also been considered part of the U.S.[26] A 2007 executive order included American Samoa in the U.S. "geographical extent", as reflected in the Federal Register.[27] American Samoa and Jarvis Island are in the Southern Hemisphere, all other U.S. territories are in the Northern Hemisphere.

Organized territories are lands under federal sovereignty (but not part of any state) which were given a measure of self-governance by Congress through an organic act subject to the Congress's plenary powers under the territorial clause of the Constitution's Article Four, section 3.[28]

Permanently inhabited territories[edit]

The U.S. has five permanently inhabited territories: Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands in the Caribbean Sea, Guam and the Northern Mariana Islands in the North Pacific Ocean, and American Samoa in the South Pacific.[note 6] About 3.6 million people in these territories are U.S. citizens,[2][3][4][5][6] and citizenship at birth is granted in four of the five territories (granted by Congress).[29][30][31][note 7] Citizenship at birth is not granted in American Samoa—American Samoa has about 32,000 non-citizen U.S. nationals.[31][32] Under U.S. law, "only persons born in American Samoa and Swains Island are non-citizen U.S. nationals" in its territories.[33] Because they are U.S. nationals, American Samoans are under U.S. protection, and can travel to the rest of the U.S. without a visa.[33] However, to become U.S. citizens, American Samoans must become naturalized citizens, like foreigners.[34][note 8] Unlike the other four inhabited territories, Congress has passed no legislation granting birthright citizenship to American Samoans.[29][note 9]

Each territory is self-governing[14] with three branches of government, including a locally elected governor and a territorial legislature.[13] Each territory elects a non-voting member (a non-voting resident commissioner in the case of Puerto Rico) to the U.S. House of Representatives.[13][38][39] They "possess the same powers as other members of the House, except that they may not vote [on the floor] when the House is meeting as the House of Representatives";[40] they debate, are assigned offices and staff funding, and nominate constituents from their territories to the Army, Navy and Marine Corps, Air Force and Merchant Marine academies.[40] They can vote in their appointed House committees on all legislation presented to the House, they are included in their party count for each committee, and they are equal to senators on conference committees. Depending on the Congress, they may also vote on the floor in the House Committee of the Whole.[13]

As of the 116th Congress (January 3, 2019 – January 3, 2021) the territories are represented by Amata Coleman Radewagen (R) of American Samoa, Michael San Nicholas (D) of Guam, Gregorio Sablan (D) of Northern Mariana Islands, Jenniffer González-Colón (R) of Puerto Rico and Stacey Plaskett (D) of U.S. Virgin Islands.[41] The District of Columbia's delegate is Eleanor Holmes Norton (D); like the district, the territories have no vote in Congress and no representation in the Senate.[42][43]

Every four years, U.S. political parties nominate presidential candidates at conventions which include delegates from the territories.[44] U.S. citizens living in the territories cannot vote in the general presidential election,[13][42] and non-citizen nationals in American Samoa cannot vote for President.[29]

The territorial capitals are Pago Pago (American Samoa), Hagåtña (Guam), Saipan (Northern Mariana Islands), San Juan (Puerto Rico) and Charlotte Amalie (U.S. Virgin Islands).[2][3][4][5][6][45][46] Their governors are Lolo Matalasi Moliga (American Samoa), Lou Leon Guerrero (Guam), Ralph Torres (Northern Mariana Islands), Wanda Vázquez Garced (Puerto Rico) and Albert Bryan (U.S. Virgin Islands).

Among the inhabited territories, Supplemental Security Income (SSI) is available only in the Northern Mariana Islands;[note 10] however in 2019 a U.S. judge ruled that the federal government's denial of SSI benefits to people in Puerto Rico is unconstitutional.[47]

American Samoa is the only U.S. territory with its own immigration system (a system separate from the United States immigration system).[48] American Samoa also has a communal land system in which ninety percent of the land is communally owned; ownership is based on Samoan ancestry.[48]

| Name (Abbreviation) | Location | Area | Population (2018) [2][3][4][5][6] |

Capital [2][3][4][5][6] |

Largest town | Status | Acquired |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polynesia (South Pacific) | 197.1 km2 (76 sq mi) | 50,826 | Pago Pago | Tafuna | Unincorporated, unorganized[note 11] | April 17, 1900 | |

| Micronesia (North Pacific) | 543 km2 (210 sq mi) | 167,772 | Hagåtña | Dededo[3] | Unincorporated, organized | April 11, 1899 | |

| Micronesia (North Pacific) | 463.63 km2 (179 sq mi) | 51,994 | Saipan [note 12] | Garapan | Unincorporated, organized (commonwealth) | November 4, 1986[note 13][50][49] | |

| Caribbean (North Atlantic) | 9,104 km2 (3,515 sq mi) | 3,294,626 | San Juan | San Juan | Unincorporated, organized (commonwealth) | April 11, 1899[51] | |

| Caribbean (North Atlantic) | 346.36 km2 (134 sq mi) | 106,977 | Charlotte Amalie[6] | Charlotte Amalie | Unincorporated, organized | March 31, 1917[52] |

History[edit]

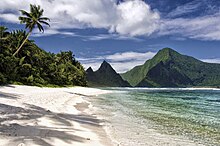

- American Samoa: territory since 1900; after the end of the Second Samoan Civil War, the Samoan Islands were divided into two regions. The U.S. took control of the eastern half of the islands.[53][54] In 1900, the Treaty of Cession of Tutuila took effect.[55] The Manuʻa islands became part of American Samoa in 1904, and Swains Island became part of American Samoa in 1925.[55] Congress ratified American Samoa's treaties in 1929.[55] For 51 years, the U.S. Navy controlled the territory.[35] American Samoa is locally self-governing under a constitution last revised in 1967.[54][note 14] The first elected governor of American Samoa was in 1977, and the first non-voting member of Congress was in 1981.[35] People born in American Samoa are U.S. nationals, but not U.S. citizens.[29][54] American Samoa is technically unorganized,[54] and its main island is Tutuila.[54]

- Guam: territory since 1899, acquired at the end of the Spanish–American War.[57] Guam is the home of Naval Base Guam and Andersen Air Force Base. It was organized under the Guam Organic Act of 1950, which granted U.S. citizenship to Guamanians and gave Guam a local government.[57] In 1968, the act was amended to permit the election of a governor.[57]

- Northern Mariana Islands: A commonwealth since 1986,[50][49] the Northern Mariana Islands were part of the Spanish Empire until 1899 and part of the German Empire from 1899 to 1919.[58] They were administered by Japan as a League of Nations mandate until the islands were conquered by the United States during World War II.[58] They became part of the United Nations Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands (TTPI) in 1947, administered by the United States as U.N. trustee.[58][49] The other constituents of the TTPI were Palau, the Federated States of Micronesia and the Marshall Islands.[59] A covenant to establish the Northern Mariana Islands as a commonwealth in political union with the United States was negotiated by representatives of both political bodies; it was approved by Northern Mariana Islands voters in 1975, and came into force on March 24, 1976.[58][4] In accordance with the covenant, the Northern Mariana Islands constitution partially took effect on January 9, 1978, and became fully effective on November 4, 1986.[4] In 1986, the Northern Mariana Islands formally left U.N. trusteeship.[50] The abbreviations "CNMI" and "NMI" are both used in the commonwealth. Most residents in the Northern Mariana Islands live on Saipan, the main island.[4]

- Puerto Rico: unincorporated territory since 1899;[51] Puerto Rico was acquired at the end of the Spanish–American War,[60] and has been a U.S. commonwealth since 1952.[61] Since 1917, Puerto Ricans have been granted U.S. citizenship.[62] Puerto Rico was organized under the Puerto Rico Federal Relations Act of 1950 (Public Law 600). In November 2008, a U.S. District Court judge ruled that a series of Congressional actions have had the cumulative effect of changing Puerto Rico's status from unincorporated to incorporated.[63] The issue is proceeding through the courts, however,[64] and the U.S. government still refers to Puerto Rico as unincorporated. A Puerto Rican attorney has called the island "semi-sovereign".[65] Puerto Rico has a statehood movement, whose goal is to make the territory the 51st state.[43][66] See also Political status of Puerto Rico.

- U.S. Virgin Islands: purchased by the U.S. from Denmark in 1917 and organized under the Revised Organic Act of the Virgin Islands in 1954. U.S. citizenship was granted in 1927.[67] The main islands are Saint Thomas, Saint John and Saint Croix.

Statistics[edit]

Except for Guam, the inhabited territories lost population in 2018. Although the territories have higher poverty rates than the mainland U.S., they have high Human Development Indexes. Four of the five territories have another official language, in addition to English.[68][69]

| Territory | Official language(s)[68][69] | Pop. change (2018) [2][3][4][5][6] |

Poverty rate (2009)[70][71] | Life expectancy in 2018 (years) [2][3][4][5][6] |

HDI[72][73] | GDP ($)[74] | Traffic flow | Time zone | Area code (+1) | Largest ethnicity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| American Samoa | English, Samoan | −1.35% | 65%[note 15] | 73.9 | 0.827 | $634 million | Right | Samoan Time (UTC−11) | 684 | Pacific Islander (Samoan)[76] |

| Guam | English, Chamorro | + 0.23% | 22.9% | 76.4 | 0.901 | $5.859 billion | Right | Chamorro Time (UTC+10) | 671 | Pacific Islander (Chamorro)[77] |

| Northern Mariana Islands | English, Chamorro, Carolinian | −0.52% | 52.3% | 75.6 | 0.875 | $1.593 billion | Right | Chamorro Time | 670 | Asian[78] |

| Puerto Rico | English, Spanish | −1.7% | 44.4%[note 16] | 81 | 0.845 | $101.131 billion | Right | Atlantic Time (UTC−4) | 787, 939 | Hispanic / Latino (Puerto Rican)[note 17][79] |

| U.S. Virgin Islands | English | −0.3% | 22.4% | 79.5 | 0.894 | $3.855 billion | Left | Atlantic Time | 340 | African-American[80] |

The territories do not have administrative counties.[note 18] The U.S. Census Bureau counts Puerto Rico's 78 municipalities, the U.S. Virgin Islands' three main islands, all of Guam, the Northern Mariana Islands' four municipalities, and American Samoa's three districts and two atolls as county equivalents.[81][82] The Census Bureau also counts each of the U.S. Minor Outlying Islands as county equivalents.[81][82]

For statistical purposes, the U.S. Census Bureau has a defined area called the "Island Areas" which consists of American Samoa, Guam, the Northern Mariana Islands, and the U.S. Virgin Islands (every major territory except Puerto Rico).[1][83][84] The U.S. Census Bureau often treats Puerto Rico as its own entity or groups it with the states and D.C. (for example, Puerto Rico has a QuickFacts page just like the states and D.C.)[85] Puerto Rico data is collected annually in American Community Survey estimates (just like the states), but data for the other territories is collected only once every ten years.[86]

Governments and legislatures[edit]

See also: Politics of American Samoa, Politics of Guam, Politics of the Northern Mariana Islands, Politics of Puerto Rico, and Politics of the U.S. Virgin Islands

The five major inhabited territories contain the following governments and legislatures:

- Government of American Samoa: American Samoa Fono

- Government of Guam: Legislature of Guam

- Government of the Northern Mariana Islands: Northern Mariana Islands Commonwealth Legislature

- Government of Puerto Rico: Legislative Assembly of Puerto Rico

- Government of the U.S. Virgin Islands: Legislature of the Virgin Islands

The legislatures of American Samoa, the Northern Mariana Islands and Puerto Rico are bicameral, while the legislatures of Guam and the U.S. Virgin Islands are unicameral.

Courts[edit]

Each of the five major territories has its own local court system:

- High Court of American Samoa

- Supreme Court of Guam

- Supreme Court of the Northern Mariana Islands

- Supreme Court of Puerto Rico

- Supreme Court of the Virgin Islands

Of the five major territories, only Puerto Rico has an Article III federal district court (i.e., equivalent to the courts in the fifty states); it became an Article III court in 1966.[87] This means that, unlike other U.S. territories, federal judges in Puerto Rico have life tenure.[87] Federal courts in Guam, the Northern Mariana Islands and the U.S. Virgin Islands are Article IV territorial courts.[87][88] The following is a list of federal territorial courts, plus Puerto Rico's court:

- District Court of Guam (Ninth Circuit)

- District Court for the Northern Mariana Islands (Ninth Circuit)

- District Court for the District of Puerto Rico (not a territorial court) (First Circuit)

- District Court of the Virgin Islands (Third Circuit)

American Samoa does not have a federal territorial court, and so federal matters in American Samoa are sent to either the District court of Hawaii or the District court of the District of Columbia.[89] American Samoa is the only permanently inhabited region of the United States with no federal court.[89]

Demographics[edit]

See also: Demographics of American Samoa, Demographics of Guam, Demographics of the Northern Mariana Islands, Demographics of Puerto Rico, and Demographics of the U.S. Virgin Islands

While the U.S. mainland is majority non-Hispanic white,[90] this is not the case for the U.S. territories. In 2010, American Samoa's population was 92.6% Pacific Islander (including 88.9% Samoan); Guam's population was 49.3% Pacific Islander (including 37.3% Chamorro) and 32.2% Asian (including 26.3% Filipino); the population of the Northern Mariana Islands was 34.9% Pacific Islander and 49.9% Asian; and the population of the U.S. Virgin Islands was 76.0% African-American.[91] In 2017, Puerto Rico's population was 99.0% Hispanic or Latino (including 95.8% Puerto Rican), and 68.9% white.[92]

Throughout the 2010s, the U.S. territories (overall) lost population. The combined population of the five inhabited territories was 4,100,594 in 2010,[1] and 3,672,195 in 2018.[2][3][4][5][6]

The U.S. territories have high religiosity rates—American Samoa has the highest religiosity rate in the United States (99.3% religious and 98.3% Christian).[2]

Economies[edit]

See also: Economy of American Samoa, Economy of Guam, Economy of the Northern Mariana Islands, Economy of Puerto Rico, and Economy of the U.S. Virgin Islands

The economies of the U.S. territories vary from Puerto Rico, which has a GDP of $101.131 billion in 2018, to American Samoa, which has a GDP of $634 million in 2017.[74] In 2018, Puerto Rico exported about $18 billion in goods, with the Netherlands as the largest destination.[93]

In 2017, Guam's GDP grew by 0.2%, the GDP of the Northern Mariana Islands grew by 25.1%, Puerto Rico's GDP shrank by 2.4%, and the U.S. Virgin Islands' GDP shrank by 1.7%.[94][95][5][96] In 2017, American Samoa's GDP shrank by 5.8%, but then grew by 2.2% in 2018.[97]

American Samoa has the lowest per capita income in the United States—it has a per capita income comparable to that of Botswana.[98] In 2010, American Samoa's per capita income was $6,311.[99] As of 2010, the Manu'a District in American Samoa had a per capita income of $5,441, the lowest of any county or county-equivalent in the United States.[99] In 2017, Puerto Rico had a median household income of $19,775 (the lowest of any state or territory in the U.S.)[100] Also in 2017, Adjuntas, Puerto Rico had a median household income of $11,680 (the lowest median household income of any county or county-equivalent in the U.S.)[101] Guam has much higher incomes (Guam had a median household income of $48,274 in 2010.)[102]

Minor outlying islands[edit]

The United States Minor Outlying Islands are small islands, atolls and reefs. Palmyra Atoll, Baker Island, Howland Island, Jarvis Island, Johnston Atoll, Kingman Reef, Midway Atoll and Wake Island are in the Pacific Ocean, and Navassa Island is in the Caribbean Sea. The additional disputed territories of Bajo Nuevo Bank and Serranilla Bank are also located in the Caribbean Sea. Palmyra Atoll (formally known as the United States Territory of Palmyra Island)[103] is the only incorporated territory, a status it has maintained since Hawaii became a state in 1959.[15]

The status of several territories is disputed. Navassa Island is disputed by Haiti,[104] Wake Island is disputed by the Marshall Islands,[105] Swains Island (part of American Samoa) is disputed by Tokelau,[106][2] and Bajo Nuevo Bank and Serranilla Bank (both administered by Colombia) are disputed by Colombia, Jamaica, Honduras, and Nicaragua.[13][107] They are uninhabited except for Midway Atoll, whose approximately 40 inhabitants are employees of the Fish and Wildlife Service and their services provider;[108] Palmyra Atoll, whose population varies from four to 20 Nature Conservancy and Fish and Wildlife staff and researchers;[109] and Wake Island, which has a population of about 100 military personnel and civilian employees.[105]

| Name | Location | Area | Status | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baker Island[a] | North Pacific Ocean | 2.1 km2 (0.81 sq mi) | Unincorporated, unorganized | Claimed under the Guano Islands Act on October 28, 1856.[110][111] Annexed on May 13, 1936, and placed under the jurisdiction of the United States Department of the Interior.[112] |

| Howland Island[a] | North Pacific Ocean | 4.5 km2 (1.7 sq mi) | Unincorporated, unorganized | Claimed under the Guano Islands Act on December 3, 1858.[110][111] Annexed on May 13, 1936, and placed under the jurisdiction of the Interior Department.[112] |

| Jarvis Island[a] | South Pacific Ocean (Polynesia) | 4.75 km2 (1.83 sq mi) | Unincorporated, unorganized | Claimed under the Guano Islands Act on October 28, 1856.[110][111] Annexed on May 13, 1936, and placed under the jurisdiction of the Interior Department.[112] |

| North Pacific Ocean | 2.67 km2 (1.03 sq mi) | Unincorporated, unorganized | Last used by the U.S. Department of Defense in 2004 | |

| Kingman Reef[a] | North Pacific Ocean | 18 km2 (6.9 sq mi) | Unincorporated, unorganized | Claimed under the Guano Islands Act on February 8, 1860.[110][111] Annexed on May 10, 1922, and placed under the jurisdiction of the Navy Department on December 29, 1934.[113] |

| North Pacific Ocean | 6.2 km2 (2.4 sq mi) | Unincorporated, unorganized | Territory since 1859; primarily a wildlife refuge and previously under the jurisdiction of the Navy Department. | |

| Caribbean Sea | 5.4 km2 (2.1 sq mi) | Unincorporated, unorganized | Territory since 1857; also claimed by Haiti[104] | |

| North Pacific Ocean | 12 km2 (5 sq mi) | Incorporated, unorganized | Partially privately owned by the Nature Conservancy, with much of the rest owned by the federal government and managed by the Fish and Wildlife Service.[114][115] It is an archipelago of about fifty small islands with a land area of about 1.56 sq mi (4.0 km2), about 1,000 miles (1,600 km) south of Oahu. The atoll was acquired through the annexation of the Republic of Hawaii in 1898. When the Territory of Hawaii was incorporated on April 30, 1900, Palmyra Atoll was incorporated as part of that territory. When Hawaii became a state in 1959, however, an act of Congress excluded the atoll from the state. Palmyra remained an incorporated territory, but received no new, organized government.[15] U.S. sovereignty over Palmyra Atoll (and Hawaii) is disputed by the Hawaiian sovereignty movement.[116][117] | |

| North Pacific Ocean (Micronesia) | 7.4 km2 (2.9 sq mi) | Unincorporated, unorganized | Territory since 1898; host to the Wake Island Airfield, administered by the U.S. Air Force. Wake Island is claimed by the Marshall Islands.[105] |

Disputed[edit]

The following two territories are claimed by multiple countries (including the United States),[13] and are not included in ISO 3166-2:UM. However, they are sometimes grouped with the U.S. Minor Outlying Islands. According to the GAO, "the United States conducts maritime law enforcement operations in and around Serranilla Bank and Bajo Nuevo [Bank] consistent with U.S. sovereignty claims."[13]

| Name | Location | Area | Status | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bajo Nuevo Bank | North Atlantic Ocean & Caribbean Sea | 110 km2 (42 sq mi) | Unincorporated, unorganized | Administered by Colombia. Claimed by the U.S. (under the Guano Islands Act) and Jamaica. A claim by Nicaragua was resolved in 2012 in favor of Colombia by the International Court of Justice, although the U.S. was not a party to that case and does not recognize the jurisdiction of the ICJ.[118] |

| Serranilla Bank | North Atlantic Ocean & Caribbean Sea | 350 km2 (140 sq mi) | Unincorporated, unorganized | Administered by Colombia; site of a naval garrison. Claimed by the U.S (since 1879 under the Guano Islands Act), Honduras, and Jamaica. A claim by Nicaragua was resolved in 2012 in favor of Colombia by the International Court of Justice, although the U.S. was not a party to that case and does not recognize the jurisdiction of the ICJ.[118] |

Incorporated and unincorporated territories[edit]

Congress decides whether a territory is incorporated or unincorporated. The U.S. constitution applies to each incorporated territory (including its local government and inhabitants) as it applies to the local governments and residents of a state. Incorporated territories are considered to be integral parts of the U.S., rather than possessions.[11][119]

The U.S. Supreme Court, in its 1901–1905 Insular Cases, ruled that the constitution extended to U.S. territories. The court also established the doctrine of territorial incorporation, in which the constitution applies fully to incorporated territories (such as the territories of Alaska and Hawaii) and partially in the unincorporated territories of Puerto Rico, Guam and, at the time, the Philippines (which is no longer a U.S. territory).[120][121]

In the 1901 Supreme Court case Downes v. Bidwell, the court said that the U.S. Constitution did not fully apply in unincorporated territories because they were inhabited by "alien races".[122][123] Joshua Keating of Slate.com calls the Insular Cases "bizarre and racist".[34]

The U.S. had no unincorporated territories (also known as overseas possessions or insular areas) until 1856. Congress enacted the Guano Islands Act that year, authorizing the president to take possession of unclaimed islands to mine guano. The U.S. has taken control of (and claimed rights on) many islands and atolls, especially in the Caribbean Sea and the Pacific Ocean, under this law; most have been abandoned. It also has acquired territories since 1856 under other circumstances, such as under the Treaty of Paris (1898) which ended the Spanish–American War. The Supreme Court considered the constitutional position of these unincorporated territories in Balzac v. People of Porto Rico, and said the following about a U.S. court in Puerto Rico:

The United States District Court is not a true United States court established under article 3 of the Constitution to administer the judicial power of the United States ... It is created ... by the sovereign congressional faculty, granted under article 4, 3, of that instrument, of making all needful rules and regulations respecting the territory belonging to the United States. The resemblance of its jurisdiction to that of true United States courts, in offering an opportunity to nonresidents of resorting to a tribunal not subject to local influence, does not change its character as a mere territorial court.[124]:312

In Glidden Company v. Zdanok, the court cited Balzac and said about courts in unincorporated territories: "Upon like considerations, Article III has been viewed as inapplicable to courts created in unincorporated territories outside the mainland ... and to the consular courts established by concessions from foreign countries ..."[125]:547 The judiciary determined that incorporation involves express declaration or an implication strong enough to exclude any other view, raising questions about Puerto Rico's status.[126]

In 1966, Congress made the United States District Court for the District of Puerto Rico an Article III district court. This (the only district court in a U.S. territory) sets Puerto Rico apart judicially from the other unincorporated territories, and U.S. district judge Gustavo Gelpi express the opinion that Puerto Rico is no longer unincorporated:

The court ... today holds that in the particular case of Puerto Rico, a monumental constitutional evolution based on continued and repeated congressional annexation has taken place. Given the same, the territory has evolved from an unincorporated to an incorporated one. Congress today, thus, must afford Puerto Rico and the 4,000,000 United States citizens residing therein all constitutional guarantees. To hold otherwise, would amount to the court blindfolding itself to continue permitting Congress per secula seculorum to switch on and off the Constitution.[127]

In Balzac, the court defined "implied":[124]:306

Had Congress intended to take the important step of changing the treaty status of Puerto Rico by incorporating it into the Union, it is reasonable to suppose that it would have done so by the plain declaration, and would not have left it to mere inference. Before the question became acute at the close of the Spanish War, the distinction between acquisition and incorporation was not regarded as important, or at least it was not fully understood and had not aroused great controversy. Before that, the purpose of Congress might well be a matter of mere inference from various legislative acts; but in these latter days, incorporation is not to be assumed without express declaration, or an implication so strong as to exclude any other view.

In 2018, a lower court ruling (Luis Segovia v. United States, in the United States Court of Appeals for the 7th Circuit) ruled that former Illinois residents living in Puerto Rico, Guam, or the U.S. Virgin Islands cannot file absentee ballots because those regions are part of the United States.[128]

In analyzing the Insular Cases, Christina Duffy Ponsa of the New York Times said the following: "To be an unincorporated territory is to be caught in limbo: although unquestionably subject to American sovereignty, they are not considered part of the United States for certain purposes but not others. Whether they are part of the United States for purposes of the Citizenship Clause remains unresolved."[10][note 19]

Supreme Court decisions about individual territories[edit]

In Rassmussen v. U.S., the Supreme Court quoted from Article III of the 1867 treaty for the purchase of Alaska:

"The inhabitants of the ceded territory ... shall be admitted to the enjoyment of all the rights, advantages, and immunities of citizens of the United States ..." This declaration, although somewhat changed in phraseology, is the equivalent ... of the formula, employed from the beginning to express the purpose to incorporate acquired territory into the United States, especially in the absence of other provisions showing an intention to the contrary.[129]:522

The act of incorporation affects the people of the territory more than the territory per se by extending the Privileges and Immunities Clause of the Constitution to them, such as its extension to Puerto Rico in 1947; however, Puerto Rico remains unincorporated.[126]

The 2016 Supreme Court case Puerto Rico v. Sanchez Valle ruled that territories do not have their own sovereignty.[8] That year, the Supreme Court declined to rule on a lower-court ruling in Tuaua v. United States that American Samoans are not U.S. citizens at birth.[36][37]

Alaska Territory[edit]

Rassmussen arose from a criminal conviction by a six-person jury in Alaska under federal law. The court held that Alaska had been incorporated into the U.S. in the treaty of cession with Russia,[130] and the congressional implication was strong enough to exclude any other view:[129]:523

That Congress, shortly following the adoption of the treaty with Russia, clearly contemplated the incorporation of Alaska into the United States as a part thereof, we think plainly results from the act of July 20, 1868, concerning internal revenue taxation ... and the act of July 27, 1868 ... extending the laws of the United States relating to customs, commerce, and navigation over Alaska, and establishing a collection district therein ... And this is fortified by subsequent action of Congress, which it is unnecessary to refer to.

Concurring justice Henry Brown agreed:[129]:533–4

Apparently, acceptance of the territory is insufficient in the opinion of the court in this case, since the result that Alaska is incorporated into the United States is reached, not through the treaty with Russia, or through the establishment of a civil government there, but from the act ... extending the laws of the United States relating to the customs, commerce, and navigation over Alaska, and establishing a collection district there. Certain other acts are cited, notably the judiciary act ... making it the duty of this court to assign ... the several territories of the United States to particular Circuits.

Florida Territory[edit]

In Dorr v. U.S., the court quoted Chief Justice John Marshall from an earlier case:[131]:141–2

The 6th article of the treaty of cession contains the following provision: "The inhabitants of the territories which His Catholic Majesty cedes the United States by this treaty shall be incorporated in the Union of the United States as soon as may be consistent with the principles of the Federal Constitution and admitted to the enjoyment of the privileges, rights, and immunities of the citizens of the United States ..." This treaty is the law of the land and admits the inhabitants of Florida to the enjoyment of the privileges, rights, and immunities of the citizens of the United States. It is unnecessary to inquire whether this is not their condition, independent of stipulation. They do not, however, participate in political power; they do not share in the government till Florida shall become a state. In the meantime Florida continues to be a territory of the United States, governed by virtue of that clause in the Constitution which empowers Congress "to make all needful rules and regulations respecting the territory or other property belonging to the United States".

In Downes v. Bidwell, the court said: "The same construction was adhered to in the treaty with Spain for the purchase of Florida ... the 6th article of which provided that the inhabitants should 'be incorporated into the Union of the United States, as soon as may be consistent with the principles of the Federal Constitution'."[132]:256

Southwest Territory[edit]

Justice Brown first mentioned incorporation in Downes:[132]:321–2

In view of this it cannot, it seems to me, be doubted that the United States continued to be composed of states and territories, all forming an integral part thereof and incorporated therein, as was the case prior to the adoption of the Constitution. Subsequently, the territory now embraced in the state of Tennessee was ceded to the United States by the state of North Carolina. In order to ensure the rights of the native inhabitants, it was expressly stipulated that the inhabitants of the ceded territory should enjoy all the rights, privileges, benefits, and advantages set forth in the ordinance of the late Congress for the government of the western territory of the United States.

Louisiana Territory[edit]

In Downes, the court said:

Owing to a new war between England and France being upon the point of breaking out, there was need for haste in the negotiations, and Mr. Livingston took the responsibility of disobeying his (Mr. Jefferson's) instructions, and, probably owing to the insistence of Bonaparte, consented to the 3d article of the treaty (with France to acquire the territory of Louisiana), which provided that "the inhabitants of the ceded territory shall be incorporated in the Union of the United States, and admitted as soon as possible, according to the principles of the Federal Constitution, to the enjoyment of all the rights, advantages, and immunities of citizens of the United States; and in the meantime they shall be maintained and protected in the free enjoyment of their liberty, property, and the religion which they profess." [8 Stat. at L. 202.] This evidently committed the government to the ultimate, but not to the immediate, admission of Louisiana as a state ...[132]:252

Former territories and administered areas[edit]

Organized incorporated territories[edit]

Unincorporated territories[edit]

- Corn Islands (1914–1971): leased for 99 years under the Bryan–Chamorro Treaty, but returned to Nicaragua when the treaty was annulled in 1970

- Line Islands: disputed claim with the United Kingdom. U.S. claim to most of the islands was ceded to Kiribati upon its independence in 1979, but the U.S. retained Kingman Reef, Palmyra Atoll and Jarvis Island

Panama Canal Zone (1903–1979): sovereignty returned to Panama under the Torrijos–Carter Treaties of 1978. The U.S. retained a military base and control of the canal until December 31, 1999.

Panama Canal Zone (1903–1979): sovereignty returned to Panama under the Torrijos–Carter Treaties of 1978. The U.S. retained a military base and control of the canal until December 31, 1999.- Philippines (1898–1946)[133]: military government, 1898–1902; insular government, 1901–1935; commonwealth government, 1935–1942 and 1945–1946 (islands under Japanese occupation, 1942–1945); granted independence on July 4, 1946

- Phoenix Islands: disputed claim with the United Kingdom; U.S. claim ceded to Kiribati upon its independence in 1979 (Baker and Howland Islands, sometimes considered part of this group, are retained by the U.S.)

- Quita Sueño Bank (1869–1981): claimed under the Guano Islands Act; claim abandoned in a September 7, 1981 treaty

- Roncador Bank (1856–1981): claimed under the Guano Islands Act; ceded to Colombia in September 7, 1981 treaty

- Serrana Bank: claimed under the Guano Islands Act; ceded to Colombia in September 7, 1981 treaty[134]

- Swan Islands (1863–1972): claimed under the Guano Islands Act; ceded to Honduras in a 1972 treaty

Administered areas[edit]

- Cuba (1899–1902 and 1906–1909)

- Dominican Republic (1916–1924 and 1965–66)

- Haiti (1915–1934)

- Nanpō Islands and Marcus Island (1945–1968): Occupied after World War II, and returned to Japan by mutual agreement

- Nicaragua (1912–1933)

- Ryukyu Islands, including Okinawa (1952–1972): returned to Japan in an agreement including the Daitō Islands[135]

Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands (1947–1986): U.N. trust territory administered by the U.S.; included the Marshall Islands, the Federated States of Micronesia, and Palau, which are sovereign states (that have entered into a Compact of Free Association with the U.S.), along with the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands.

Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands (1947–1986): U.N. trust territory administered by the U.S.; included the Marshall Islands, the Federated States of Micronesia, and Palau, which are sovereign states (that have entered into a Compact of Free Association with the U.S.), along with the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands.- Veracruz (1914): after the Tampico Affair during the Mexican Revolution

Other zones[edit]

- Participation in the Occupation of the Rhineland (1918–1921)

- Occupation of Greenland (1941–1945)[136]

- Occupation of Iceland in World War II (1941–1946);[136] military base retained until 2006.

- Allied Military Government for Occupied Territories, in Allied-controlled sections of Italy from the July 1943 invasion of Sicily until the September armistice with Italy. AMGOT continued in newly liberated areas of Italy until the end of the war, and also existed in France.[citation needed]

- Clipperton Island (1944–1945): occupied territory, returned to France on October 23, 1945.

- United States Army Military Government in Korea: Occupation south of the 38th parallel from 1945 to 1948.

- American zones of Allied-occupied Germany (1945–1949)

- Occupation of Japan (1945–1952) after World War II

- American occupation zones in Allied-occupied Austria and Vienna (1945–1955)

- American occupation zone in West Berlin (1945–1990)

- Free Territory of Trieste (1947–1954): The U.S. co-administered a portion of the territory (between the Kingdom of Italy and the former Kingdom of Yugoslavia) with the United Kingdom.

- Grenada invasion and occupation (1983)

- Coalition Provisional Authority (Iraq, 2003–2004)

- Green Zone, Iraq (March 20, 2003 – December 31, 2008)[137]

Flora and fauna[edit]

This section may stray from the topic of the article. (July 2019) |

Further information: Fauna of the United States: territories

The territories of the United States have many plant and animal species found nowhere else in the United States.[138] All U.S. territories have tropical climates and ecosystems.[138]

Forests[edit]

The USDA says the following about the U.S. territories (plus Hawaii):

[The U.S. territories, plus Hawaii] include virtually all the Nation's tropical forests as well as other forest types including subtropical, coastal, subalpine, dry limestone, and coastal mangrove forests. Although distant from America's geographic center and from each other—and with distinctive flora and fauna, land use history, and individual forest issues—these rich and diverse ecosystems share a common bond of change and challenge.[138]

Forests in the U.S. territories are vulnerable to invasive species and new housing developments.[138] El Yunque National Forest in Puerto Rico is the only tropical rain forest in the United States National Forest system.[139]

American Samoa has 80.84% forest cover and the Northern Mariana Islands has 80.37% forest cover—these are among the highest forest cover percentages in the United States (only Maine and New Hampshire are higher).[140]

Birds[edit]

See also: Birds of American Samoa, Birds of Guam, Birds of the Northern Mariana Islands, Birds of Puerto Rico, Birds of the U.S. Virgin Islands, Birds of the U.S. Minor Outlying Islands, and List of birds of the United States

U.S. territories have many bird species that are endemic (not found in any other location).[138]

Introduction of the invasive brown tree snake has harmed Guam's native bird population—nine of twelve endemic species have become extinct, and the territorial bird (the Guam rail) is extinct in the wild.[138]

Puerto Rico has several endemic bird species, such as the critically endangered Puerto Rican parrot, the Puerto Rican flycatcher, and the Puerto Rican spindalis.[141] The Northern Mariana Islands has the Mariana swiftlet, Mariana crow, Tinian monarch and golden white-eye (all endemic).[142] American Samoa is the only area of the United States where the many-colored fruit dove can be found—it can be found in the National Park of American Samoa.[143] Other birds found in American Samoa include the blue-crowned lorikeet and the Samoan starling.[144]

The Wake Island rail (now extinct) was endemic to Wake Island,[145] and the Laysan duck is endemic to Midway Atoll and the Northwest Hawaiian Islands.[146] Palmyra Atoll has the second-largest red-footed booby colony in the world,[147] and Midway Atoll has the largest breeding colony of Laysan albatross in the world.[148][149]

The American Birding Association currently excludes the U.S. territories from their "ABA Area" checklist.[150]

Other animals[edit]

See also: Mammals of American Samoa, Mammals of Guam, Mammals of the Northern Mariana Islands, Mammals of Puerto Rico, Mammals of the U.S. Virgin Islands, Mammals of the U.S. Minor Outlying Islands, Reptiles of American Samoa, Reptiles of Puerto Rico, Fauna of Puerto Rico, and Fauna of the U.S. Virgin Islands

American Samoa has several reptile species, such as the Pacific boa (on the island of Ta‘ū) and Pacific slender-toed gecko.[151] American Samoa has only a few mammal species, such as the Pacific (Polynesian) sheath-tailed bat, as well as oceanic mammals such as the Humpback whale.[152][153] Guam and the Northern Mariana Islands also have a small number of mammals, such as the Mariana fruit bat;[154] oceanic mammals include Fraser's dolphin and the Sperm whale. The fauna of Puerto Rico includes the common coquí (frog),[155] while the fauna of the U.S. Virgin Islands includes species found in Virgin Islands National Park (including 302 species of fish).[156]

American Samoa has a location called Turtle and Shark which is important in Samoan culture and mythology.[157]

Public image[edit]

In The Not-Quite States of America, his book about the U.S. territories, Doug Mack said:

It seemed that right around the turn of the twentieth century, the territories were part of the national mythology and the everyday conversation ... A century or so ago, Americans didn't just know about the territories but cared about them, argued about them. But what changed? How and why did they disappear from the national conversation?[158] The territories have made us who we are. They represent the USA's place in the world. They've been a reflection of our national mood in nearly every period of American history.[159]

Organizations such as Facebook view U.S. territories as not being part of the United States—instead, they are viewed as equivalent to foreign countries.[160] In response to Facebook's view, former Guam representative Madeleine Bordallo said, "It is an injustice that Americans living in the U.S. territories are not treated as other Americans living in the states. [...] Treating residents of Guam and other U.S. territories as living outside the United States and excluding them from programs perpetuates misconceptions and injustices that have long had a negative impact on our communities".[160]

Representative Stephanie Murphy of Florida said about a 2018 bill to make Puerto Rico the 51st state, "The hard truth is that Puerto Rico's lack of political power allows Washington to treat Puerto Rico like an afterthought."[161] According to Governor of Puerto Rico Ricardo Rosselló, "Because we don't have political power, because we don't have representatives, [no] senators, no vote for president, we are treated as an afterthought."[162] Rosselló called Puerto Rico the "oldest, most populous colony in the world".

Rosselló and others have referred to the U.S. territories as American "colonies".[163][164][165][166][10] David Vine of the Washington Post said the following: "The people of [the U.S. territories] are all too accustomed to being forgotten except in times of crisis. But being forgotten is not the worst of their problems. They are trapped in a state of third-class citizenship, unable to access full democratic rights because politicians have long favored the military's freedom of operation over protecting the freedoms of certain U.S. citizens."[166] In his article How the U.S. Has Hidden Its Empire, Daniel Immerwahr of The Guardian writes, "The confusion and shoulder-shrugging indifference that mainlanders displayed [toward territories] at the time of Pearl Harbor hasn't changed much at all. [...] [Maps of the contiguous U.S.] give [mainlanders] a truncated view of their own history, one that excludes part of their country."[164] The 2020 U.S. Census excludes non-citizen U.S. nationals in American Samoa—in response to this, Mark Stern of Slate.com said, "The Census Bureau's total exclusion of American Samoans provides a pertinent reminder that, until the courts step in, the federal government will continue to treat these Americans with startling indifference."[167]

Galleries[edit]

Members of the House of Representatives[edit]

Amata Coleman Radewagen (American Samoa)

Michael San Nicolas (Guam)

Gregorio Sablan (Northern Mariana Islands)

Jenniffer González (Puerto Rico)

Stacey Plaskett (U.S. Virgin Islands)

Territorial governors[edit]

Satellite images[edit]

Inhabited territories[edit]

Uninhabited territories (minor outlying islands)[edit]

Maps[edit]

See also[edit]

- Article indexes: AS, GU, MP, PR, VI

- Congressional districts: AS, GU, MP, PR, VI

- Enabling act (United States)

- Extreme points of the United States

- Geography: AS, GU, MP, PR, VI

- Geology: AS, GU, MP, PR, VI

- Hawaiian Organic Act

- Historic regions of the United States

- Legal status of Hawaii

- List of museums in the U.S. territories

- List of U.S. National Historic Landmarks in the U.S. territories

- Organic Acts of 1845–46

- Organized incorporated territories of the United States

- Per captia income: AS, GU, MP, PR, VI

- Political status of Puerto Rico

- Territories of the United States on stamps

- Unincorporated territories of the United States

- United States National Register of Historic Places listings:

- United States territory

- Unorganized territory

Outlines[edit]

- Outline of American Samoa

- Outline of Guam

- Outline of the Northern Mariana Islands

- Outline of Puerto Rico

- Outline of the U.S. Virgin Islands

Notes[edit]

- ^ Note: This number is produced by adding the five 2018 population estimates presented by the CIA World Factbook.

- ^ According to the 2016 Supreme Court ruling Puerto Rico v. Sanchez Valle, territories are not sovereign.[8]

- ^ Two additional territories (Bajo Nuevo Bank and Serranilla Bank) are claimed by the United States but administered by Colombia—if these two territories are counted, the total number of U.S. territories is sixteen.

- ^ Some residents of Sikaiana (also known as the Stewart Islands) believe that Sikaiana is part of the United States: "They base their claim on the assertion that the Stewart Islands were ceded to King Kamehameha IV and accepted by him as part of the Kingdom of Hawaii in 1856 and, thus, were part of the Republic of Hawaii (which was declared in 1893) when it was annexed to the United States by law in 1898." However, Sikaiana was not included within "Hawaii and its dependencies".[16]

- ^ The Federated States of Micronesia, the Marshall Islands and Palau are in free association with the United States.[11]

- ^ Two territories (Puerto Rico and the Northern Mariana Islands) are called "commonwealths".

- ^ The New York Times notes, "Even in [the four] territories, where statutory birthright citizenship has provided a makeshift solution for many decades, doubt, confusion and anxiety over the extent to which citizenship is constitutionally guaranteed have persisted for more than a century."[10]

- ^ Non-citizen U.S. nationals also cannot serve on a jury, vote, obtain certain government jobs, or run for office.[31][35] For U.S. nationals who attempt to naturalize, there is no guarantee that they will become citizens.[31]

- ^ In Tuaua v. United States, it was ruled that citizenship-at-birth is not a right in unincorporated regions of the U.S.—current citizenship-at-birth in Guam, the Northern Mariana Islands, Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands is granted only because the U.S. Congress passed legislation granting citizenship to those territories. The Supreme Court declined to rule on the case.[36][37]

- ^ SSI benefits are available only in the fifty states, the District of Columbia and the Northern Mariana Islands

- ^ American Samoa, technically unorganized, is de facto organized.

- ^ The administrative center of the Northern Mariana Islands is Capitol Hill, Saipan. However, because Saipan is governed as a single municipality, most publications refer to the capital as "Saipan".

- ^ U.S. sovereignty took effect on November 3, 1986 (Eastern Time) and on November 4, 1986 (local Northern Mariana Islands Chamorro Time).[49]

- ^ The revised constitution of American Samoa was approved on June 2, 1967 by Stewart L. Udall, then U.S. Secretary of the Interior, under authority granted on June 29, 1951. It became effective on July 1, 1967.[56]

- ^ 2017 poverty rate;[23] in 2009, American Samoa's poverty rate was 57.8%[75]

- ^ 2017 rate.

- ^ The largest racial group is white, in addition to Hispanic/Latino.[5]

- ^ American Samoa is divided into 14 counties, but the U.S. Census Bureau treats these counties as minor civil divisions.[81][82]

- ^ Though Tuaua v. United States ruled that American Samoans aren't entitled to birthright citizenship, the issue has never been resolved at the Supreme Court level.

References[edit]

- ^ a b c https://www.census.gov/prod/cen2010/cph-2-1.pdf United States Summary: 2010. Population and Housing Unit Counts. Issued September 2012. Page 1 (Page 49 of PDF). Retrieved July 4, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/aq.html CIA World Factbook. American Samoa. Retrieved July 4, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/gq.html CIA World Factbook—Guam. Retrieved July 4, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "Australia—Oceania :: Northern Mariana Islands—The World Factbook—Central Intelligence Agency". CIA World Factbook. Retrieved June 30, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/rq.html CIA World Factbook—Puerto Rico. Retrieved July 4, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/vq.html CIA World Factbook—Virgin Islands (U.S.) Retrieved July 4, 2019.

- ^ "Definition of Terms—1120 Acquisition of U.S. Nationality in U.S. Territories and Possessions". U.S. Department of State Foreign Affairs Manual Volume 7—Consular Affairs. U.S. Department of State. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 22, 2015. Retrieved January 10, 2016.

- ^ a b c Wolf, Richard (June 9, 2016). "Puerto Rico not sovereign, Supreme Court says". USA Today. Retrieved January 19, 2018.

- ^ a b "Definitions of Insular Area Political Organizations". U.S. Department of the Interior. June 12, 2015.

- ^ a b c d Duffy Ponsa, Christina (June 8, 2016). "Are American Samoans American?". The New York Times. Retrieved July 4, 2019.

- ^ a b c https://www.princeton.edu/~ota/disk2/1987/8712/871204.PDF Princeton.edu. Chapter 2: Introduction. (Renewable Resource Management for U.S. Insular Areas—Integrated.) Page 40 (Page 4 of PDF). Retrieved July 4, 2019.

- ^ a b https://www.worldatlas.com/articles/the-territories-of-the-united-states.html Worldatlas.com. "What Are The U.S. Territories?" Retrieved July 4, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "U.S. Insular Areas: application of the U.S. Constitution" (PDF). U.S. General Accounting Office Report. November 1997. pp. 10 / 1, 6, 39 / 8, 14, 26–28. Retrieved June 30, 2019.

- ^ a b https://harvardlawreview.org/2017/04/us-territories-introduction/ Harvard Law Review—U.S. Territories: Introduction. April 10, 2017. Retrieved July 2019.

- ^ a b c "Palmyra Atoll". U.S. Department of the Interior Office of Insular Affairs. Retrieved 23 June 2010.

- ^ U.S. Insular Areas. Application of the U.S. Constitution (PDF) (Report). United States General Accounting Office. November 1997. p. 39. Retrieved September 19, 2018.

- ^ Van Dyke, Jon M.; Richardson, William S. (March 23, 2007). "Unresolved Maritime Boundary Problems in the Caribbean" (PDF). Harte Research Institute for Gulf of Mexico Studies. Retrieved January 30, 2018.

- ^ "Bajo Nuevo Bank (Petrel Islands) and Serranilla Bank". Wondermondo.com. Retrieved January 30, 2018.

- ^ United States Summary, 2010: Population and housing unit counts. U.S. Department of Commerce, Economics and Statistics Administration, U.S. Census Bureau. 2012.

- ^ Smith, Gary Alden (February 28, 2011). State and National Boundaries of the United States. McFarland. p. 170. ISBN 9781476604343.

- ^ Gold, Susan Dudley (September 2010). Missouri Compromise. Marshall Cavendish. pp. 33. ISBN 9781608700417.

- ^ Murph, Darren. "The most expensive internet in America: fighting to bring affordable broadband to American Samoa". Engadget. Retrieved November 24, 2017.

- ^ a b Sagapolutele, Fili (March 2, 2017). "American Samoa Governor Says Small Economies 'Cannot Afford Any Reduction In Medicaid' | Pacific Islands Report". www.pireport.org. Retrieved January 9, 2018.

- ^ "Poverty Determination in U.S. Insular Areas" (PDF). Retrieved January 9, 2018.

- ^ Bartholomew H. Sparrow (2005). Sanford Levinson; Bartholomew H. Sparrow (eds.). The Louisiana Purchase and American Expansion, 1803–1898. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 232. ISBN 978-0-7425-4984-5. Retrieved December 2, 2012.

- ^ a b "8 FAM 301.1 (U) ACQUISITION BY BIRTH IN THE UNITED STATES". State Department Foreign Affairs Manual (FAM). Retrieved July 18, 2018.

- ^ "Executive Order 13423—Strengthening Federal Environmental, Energy, and Transportation Management" (PDF). United States Department of State. § 9(l).

- ^ U.S. Const. art. IV, § 3, cl. 2 ("The Congress shall have Power to dispose of and make all needful Rules and Regulations respecting the Territory or other Property belonging to the United States ...").

- ^ a b c d "American Samoa and the Citizenship Clause: A Study in Insular Cases Revisionism". Harvard Law Review. Retrieved January 5, 2018.

- ^ http://www.samoanews.com/linking-samoans/am-samoans-arent-actually-citizens Samoanews.com. American Samoans Aren't Actually Citizens. Retrieved July 1, 2019.

- ^ a b c d https://news.nationalgeographic.com/2018/03/american-samoa-citizenship-lawsuit-history/ National Geographic. "Why Are American Samoans Not U.S. Citizens?" Heather Brady. March 30, 2018. Retrieved July 1, 2019.

- ^ Nativity by Place of Birth and Citizenship Status Archived 2020-02-14 at Archive.today, United States Census, 2010.

- ^ a b 8 FAM 301.1-1(b). State Department Foreign Affairs Manual (FAM) Vol 8. However, as reported in Samoa lawsuit, Newsweek, July 13, 2012. viewed December 16, 2012.

- ^ a b Joshua Keating. (June 15, 2015). "How Come American Samoans Still Don't Have U.S. Citizenship at Birth?". Slate. Retrieved January 1, 2018.

- ^ a b c https://www.latimes.com/nation/la-na-american-samoan-citizenship-explainer-20180406-story.html Los Angeles Times. Ann M. Simmons. American Samoans Aren't Actually U.S. Citizens. Does That Violate The Constitution? April 6, 2018. Retrieved July 1, 2019.

- ^ a b http://www.latimes.com/nation/la-na-court-samoans-20160613-snap-story.html Supreme Court rejects citizenship for American Samoans. David G. Savage. June 13, 2016. Latimes.com. Retrieved 30 January 2018.

- ^ a b http://www.equalrightsnow.org/case_overview About Tuaua v. United States. Equalrightsnow.org. Retrieved 30 January 2018.

- ^ "Common Core Document of the United States of America". U.S. Department of State. December 30, 2011. Retrieved September 3, 2015.

- ^ "The United Nations and Decolonization". United Nations. Retrieved September 3, 2015.

- ^ a b "The House Explained". U.S. House of Representatives. Retrieved January 26, 2013.

- ^ "United States House of Representatives Directory". Archived from the original on 2019-06-28. Retrieved June 30, 2019.

- ^ a b Locker, Melissa (March 9, 2015). "Watch John Oliver Cast His Ballot for Voting Rights for U.S. Territories". Time. Retrieved January 1, 2018.

- ^ a b Cohn, Alicia (September 19, 2018). "Puerto Rico governor asks Trump to consider statehood". The Hill. Retrieved September 22, 2018.

- ^ "2016 Presidential Primaries, Caucuses, and Conventions Alphabetically by State". Green Papers. Retrieved September 3, 2015.

- ^ "Dependencies and Areas of Special Sovereignty". U.S. Department of State.

- ^ Mack, Doug. The Not-Quite States of America: Dispatches from the Territories and Other Far-Flung Outposts of the USA. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-24760-2.

- ^ http://www.startribune.com/judge-s-ruling-pushes-puerto-rico-to-pursue-ssi-benefits/505323232/ Archived 2019-02-05 at the Wayback Machine Startribune.com. Judge's Ruling Pushes Puerto Rico to Pursue SSI Benefits. Danica Coto. February 4, 2019. Retrieved July 4, 2019.

- ^ a b https://www.doi.gov/oia/islands/american-samoa Department of the Interior—American Samoa. Retrieved July 4, 2019.

- ^ a b c d "8 FAM 302.6 ACQUISITION BY BIRTH IN THE COMMONWEALTH OF THE NORTHERN MARIANA ISLANDS". fam.state.gov. Retrieved October 31, 2018.

- ^ a b c "Proclamation 5564—United States Relations With the Northern Mariana Islands, Micronesia, and the Marshall Island". The American Presidency Project. Retrieved October 31, 2018.

- ^ a b Firestone, Michelle (September 25, 2017). "Puerto Rico's Status Explained. ECSU Takes A Look At Island's History" (PDF). Retrieved November 13, 2018.

- ^ https://www.loc.gov/item/today-in-history/march-31 Library of Congress. Today in History—March 31 (Virgin Islands). Retrieved July 4, 2019.

- ^ "History of Samoa—Samoa.travel". www.samoa.travel. Retrieved November 12, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e "American Samoa | Culture, History, & People". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved November 12, 2018.

- ^ a b c "American Samoa". Pacific Islands Benthic Habitat Mapping Center. Retrieved September 22, 2018.

- ^ IBP USA (2009), SAMOA American Country Study Guide: Strategic Information and Developments, Int'l Business Publications, pp. 49–64, ISBN 978-1-4387-4187-1, retrieved October 20, 2011

- ^ a b c "Guam | History, Geography, & Points of Interest". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved November 12, 2018.

- ^ a b c d "Northern Mariana Islands | history—geography". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved October 31, 2018.

- ^ "Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands | former United States territory, Pacific Ocean". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved October 31, 2018.

- ^ "Milestones: 1866–1898—Office of the Historian". history.state.gov. Retrieved November 12, 2018.

- ^ https://www.worldatlas.com/articles/when-did-puerto-rico-become-a-commonwealth.html Worldatlas.com. "When Did Puerto Rico Become A Commonwealth?" Retrieved July 4, 2019.

- ^ https://www.smithsonianmag.com/travel/puerto-rico-history-and-heritage-13990189/ Smithsonian Magazine. Puerto Rico—History and Heritage. Retrieved July 4, 2019.

- ^ "Consejo de Salud Playa Ponce v. Johnny Rullan" (PDF).

- ^ Gelpí, Hon. Gustavo A. "The Insular Cases: A Comparative Historical Study of Puerto Rico, Hawai'i, and the Philippines" (PDF). The Federal Lawyer (March/April 2011): 25. Retrieved February 18, 2019.

- ^ Stern, Mark Joseph (January 14, 2016). "The Supreme Court Ponders Whether Puerto Rico Is a Fake State or a Real Colony". Slate Magazine. Retrieved January 19, 2018.

- ^ Mosbergen, Dominique (June 28, 2018). "Bipartisan Bill Seeks To Make Puerto Rico The 51st U.S. State By 2021". Huffington Post. Retrieved September 22, 2018.

- ^ "8 U.S. Code § 1406—Persons living in and born in the Virgin Islands". LII / Legal Information Institute. Retrieved September 21, 2018.

- ^ a b "Language situation in the U.S. | About World Languages". aboutworldlanguages.com. Retrieved 17 January 2018.

- ^ a b "Virgin Islands Language". Virgin Islands. Retrieved 17 January 2018.

- ^ "POVERTY STATUS IN 2009 BY AGE Universe: Population for whom poverty status is determined more information 2010 U.S. Virgin Islands Summary File". U. S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on 17 January 2019. Retrieved 9 January 2018.

"POVERTY STATUS IN 2009 BY AGE Universe: Population for whom poverty status is determined more information 2010 Guam Summary File". U. S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on 17 January 2019. Retrieved 9 January 2018.

"POVERTY STATUS IN 2009 BY AGE Universe: Population for whom poverty status is determined more information 2010 Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands Summary File". U. S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on 17 January 2019. Retrieved 9 January 2018.

"POVERTY STATUS IN 2009 BY AGE Universe: Population for whom poverty status is determined more information 2010 American Samoa Summary File". U. S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on 17 January 2019. Retrieved 9 January 2018. - ^ "U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts: Puerto Rico". U. S. Census Bureau. Retrieved 9 January 2018.

- ^ A. Hastings, David. "Filling Gaps In The Human Development Index: Findings For Asia And The Pacific" (PDF). United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (ESCAP). Retrieved 9 January 2018.

- ^ R. Fuentes-Ramírez, Ricardo (14 May 2017). "Human Development Index Trends and Inequality in Puerto Rico 2010–2015". Ceteris Paribus. Archived from the original on 20 October 2017. Retrieved 9 January 2018.

- ^ a b "American Samoa | Data". data.worldbank.org. Retrieved June 30, 2019.

"Virgin Islands (U.S.) | Data". data.worldbank.org. Retrieved June 30, 2019.

"Northern Mariana Islands | Data". data.worldbank.org. Retrieved June 30, 2019.

"Guam | Data". data.worldbank.org. Retrieved June 30, 2019.

"Puerto Rico | Data". data.worldbank.org. Retrieved June 30, 2019. - ^ "GAO—American Samoa and the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands—Economic Indicators Since Minimum Wage Increases Began" (PDF). U.S. Government Accountability Office. March 2014. p. 39. Retrieved October 7, 2018.

- ^ https://factfinder.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?pid=DEC_10_DPAS_ASDP1&prodType=table Archived 2017-05-03 at the Wayback Machine American Factfinder. Profile of General Demographic Characteristics: 2010. 2010 American Samoa Demographic Profile Data. Retrieved July 2019.

- ^ https://factfinder.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?pid=DEC_10_DPGU_GUDP1&prodType=table Archived 2020-02-14 at Archive.today American FactFinder. Profile of General Demographic Characteristics: 2010. 2010 Guam Demographic Profile Data. Retrieved July 4, 2019.

- ^ https://factfinder.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?pid=DEC_10_DPMP_MPDP1&prodType=table Archived 2020-02-12 at Archive.today American Factfinder. Profile of General Demographic Characteristics: 2010. 2010 Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands Demographic Profile Data. Retrieved July 4, 2019.

- ^ https://factfinder.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?pid=ACS_17_5YR_DP05&prodType=table Archived 2020-02-14 at Archive.today American Factfinder. ACS Demographic and Housing Estimates. 2013–2017 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates. Retrieved July 4, 2019.

- ^ https://factfinder.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?pid=DEC_10_DPVI_VIDP1&prodType=table[permanent dead link] American FactFinder. Profile of General Demographic Characteristics: 2010. 2010 U.S. Virgin Islands Demographic Profile Data. Retrieved July 4, 2019.

- ^ a b c "2010 FIPS Codes for Counties and County Equivalent Entities". Census.gov. Retrieved September 22, 2018.

- ^ a b c "States, Counties, and Statistically Equivalent Entities (Chapter 4)" (PDF). Retrieved September 22, 2018.

- ^ http://www.census.gov/prod/cen2010/doc/dpsfvi.pdf U.S. Virgin Islands Demographic Profile Summary File. March 2014. Page 7-1 (page 79 of the PDF). Retrieved July 4, 2019.

- ^ https://catalog.data.gov/dataset/u-s-state-boundaries Data.gov Catalog. U.S. State Boundaries. Retrieved July 1, 2019.

- ^ https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/PR U.S. Census Bureau. QuickFacts—Puerto Rico. Retrieved July 4, 2019.

- ^ https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/section-1557-top-15-languages-faqs.pdf Frequently Asked Questions to Accompany the Estimates of at Least the Top 15 Languages Spoken by Individuals with Limited English Proficiency under Section 1557 of the Affordable Care Act (ACA). U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office for Civil Rights (OCR). Page 2. Retrieved July 4, 2019.

- ^ a b c https://www.fjc.gov/history/courts/territorial-courts Federal Judicial Center—Territorial Courts. Retrieved July 1, 2019.

- ^ https://thebusinessprofessor.com/knowledge-base/article-iv-territorial-courts/ The Business Professor. Article IV Territorial Courts. Retrieved July 4, 2019.

- ^ a b https://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-08-1124T GAO (U.S. Government Accountability Office. AMERICAN SAMOA: Issues Associated with Some Federal Court Options. September 18, 2008. Retrieved July 2019.

- ^ https://factfinder.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?pid=ACS_17_5YR_DP05&prodType=table Archived 2020-02-14 at Archive.today American Factfinder. ACS Demographic and Housing Estimates. 2013-2017 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates. [Geography set to "United States". Note that "United States" in this case excludes the U.S. territories.] Retrieved September 2, 2019.

- ^ https://factfinder.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?pid=DEC_10_DPAS_ASDP1&prodType=table Archived 2017-05-03 at the Wayback Machine

https://factfinder.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?pid=DEC_10_DPGU_GUDP1&prodType=table Archived 2016-04-13 at the Wayback Machine

https://factfinder.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?pid=DEC_10_DPMP_MPDP1&prodType=table Archived 2018-11-06 at the Wayback Machine

https://factfinder.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?pid=DEC_10_DPVI_VIDP1&prodType=table[permanent dead link]

American FactFinder. Profile of General Demographic Characteristics: 2010. 2010 American Samoa / Guam / Northern Mariana Islands / United States Virgin Islands Demographic Profile data. Retrieved September 2, 2019. - ^ https://factfinder.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?pid=ACS_17_5YR_DP05&prodType=table Archived 2020-02-14 at Archive.today American FactFinder. ACS Demographic and Housing Estimates. 2013-2017 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates. [Geography set to "Puerto Rico"]. Retrieved September 2, 2019.

- ^ http://tse.export.gov/tse/MapDisplay.aspx ITA. International Trade Administration. 2018 NAICS Total All Merchandise Exports from Puerto Rico. Retrieved July 4, 2019.

- ^ https://www.bea.gov/news/2018/guam-gdp-increases-2017 BEA.gov. Guam GDP Increases in 2017. Retrieved September 2, 2019.

- ^ https://www.bea.gov/news/blog/2018-10-17/northern-mariana-islands-gdp-increases-2017 BEA.gov. Northern Mariana Islands' GDP increases in 2017. Retrieved September 2, 2019.

- ^ https://www.bea.gov/news/2018/us-virgin-islands-gdp-decreases-2017 BEA.gov. U.S. Virgin Islands GDP Decreases in 2017. Retrieved September 2, 2019.

- ^ https://www.bea.gov/news/2019/american-samoa-gdp-increases-2018 BEA.gov. American Samoa GDP Increases in 2018. Retrieved September 2, 2019.

- ^ https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2017-04/documents/american_samoa_visible_difference_final_report_2017.pdf EPA. Making a Visible Difference In American Samoa (Final Report). Retrieved September 2, 2019.

- ^ a b https://factfinder.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?pid=DEC_10_DPAS_ASDP3&prodType=table Archived 2020-02-14 at Archive.today American FactFinder. Profile of Selected Economic Characteristics: 2010. 2010 American Samoa Demographic Profile Data. [Geography set to "Manu'a District, American Samoa" or "American Samoa"]. Retrieved August 30, 2019.

- ^ https://factfinder.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?pid=ACS_17_5YR_S1901&prodType=table Archived 2020-02-14 at Archive.today American FactFinder. Income in the Past 12 Months (in 2017 Inflation-Adjusted Dollars). 2013-2017 American Community Survey 5-Year estimates [Geography set to "Puerto Rico"]. Retrieved August 30, 2019.

- ^ https://factfinder.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?pid=ACS_17_5YR_S1901&prodType=table Archived 2020-02-14 at Archive.today American FactFinder (U.S. Census)—"Income in the past 12 months (in 2017 inflation-adjusted dollars). 2013-2017 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates." [Geography set to "Adjuntas, Puerto Rico"]

- ^ https://factfinder.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?pid=DEC_10_DPGU_GUDP3&prodType=table[permanent dead link] American FactFinder. Profile of Selected Economic Characteristics: 2010. 2010 Guam Demographic Profile Data.

- ^ Act of Admission, § 2, Pub. L. No. 86-3, 73 Stat. 4 (March 18, 1959).

- ^ a b c "Australia-Oceania: Wake Island". CIA World Factbook. Archived from the original on January 31, 2019. Retrieved March 2, 2019.

- ^ https://www.tokelau.org.nz/About+Us/Geography.html Government of Tokelau—Geography. Retrieved July 4, 2019.

- ^ "Dependencies and Areas of Special Sovereignty". U.S. Department of State.

Chart, under "Sovereignty", lists nine places under U.S. sovereignty that are administered by the U.S. Department of the Interior: Baker Island, Howland Island, Jarvis Island, Johnston Atoll, Kingman Reef, the Midway Islands, Navassa Island, Palmyra Atoll, and Wake Island.

- ^ "Australia-Oceania: Midway Islands". CIA World Factbook. Archived from the original on January 21, 2019. Retrieved March 2, 2019.

- ^ "Australia-Oceania: United States Pacific Island Wildlife Refuges". CIA World Factbook. Archived from the original on February 16, 2019. Retrieved March 2, 2019.

- ^ a b c d Moore, John Bassett (1906). "A Digest of International Law as Embodied in Diplomatic Discussions, Treaties and Other International Agreements, International Awards, the Decisions of Municipal Courts, and the Writings of Jurists and Especially in Documents, Published and Unpublished, Issued by Presidents and Secretaries of State of the United States, the Opinions of the Attorneys-General, and the Decisions of Courts, Federal and State". Washington, D. C.: U.S. Government Printing Office. pp. 566–580.

- ^ a b c d "Acquisition Process of Insular Areas". United States Department of the Interior Office of Insular Affairs. 2015-06-12. Retrieved July 15, 2016.

- ^ a b c Exec. Order No. 7368 (May 13, 1936; in English) President of the United States

- ^ "Kingman Reef". Office of Insular Affairs. 2015-06-12. Retrieved July 15, 2016.

- ^ "AUSTRALIA-OCEANIA :: UNITED STATES PACIFIC ISLAND WILDLIFE REFUGES (TERRITORIES OF THE US)". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency.

- ^ "DOI Office of Insular Affairs (OIA)—Palmyra Atoll". 31 October 2007. Archived from the original on 31 October 2007.

- ^ http://www.pireport.org/articles/2000/02/11/us-purchase-palmyra-hits-impasse Pireport.org. U.S. Purchase of Palmyra Hits Impasse. February 10, 2000. Retrieved July 4, 2019.

- ^ https://www.culturalsurvival.org/publications/cultural-survival-quarterly/struggle-hawaiian-sovereignty-introduction Trask, Haunani-Kay. "The Struggle For Hawaiian Sovereignty—Introduction". Retrieved June 2019.

- ^ a b International Court of Justice (2012). "Territorial and maritime dispute (Nicaragua vs Colombia)" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 May 2013. Retrieved 29 June 2013.

- ^ "Definitions of insular area political organizations". Office of Insular Affairs, U.S. Department of the Interior. 2015-06-12. Retrieved September 30, 2017.

- ^ "Consejo de Salud Playa de Ponce v. Johnny Rullan, Secretary of Health of the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico, pages 6–7" (PDF). United States District Court for the District of Puerto Rico. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 10, 2011. Retrieved February 4, 2010.

- ^ "The Insular Cases: The Establishment of a Regime of Political Apartheid (2007) Juan R. Torruella" (PDF). Retrieved February 5, 2010.

- ^ https://www.huffpost.com/entry/john-oliver-puerto-rico_n_6833310 The Huffington Post. John Oliver Explains Outdated, Racist Logic Behind Restricting Puerto Rican Voting Rights. Roque Planas. March 9, 2015. Retrieved July 1, 2019.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

AtlanticBlackStarwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b "Balzac v. People of Porto Rico". U.S. Supreme Court. April 10, 1922. Retrieved October 4, 2017 – via FindLaw.

- ^ "Glidden Company v. Zdanok". U.S. Supreme Court. June 25, 1962. Retrieved October 4, 2017 – via FindLaw.

- ^ a b http://www.caribbeanbusiness.com/is-puerto-rico-on-a-path-to-incorporation Is Puerto Rico On A Path To Incorporation? Eva Lloréns Vélez. February 13, 2017. Retrieved 17 January 2018.

- ^ "CONSEJO DE SALUD PLAYA DE PONCE, et.al Plaintiffs v. JOHNNY RULLAN, SECRETARY OF HEALTH OF THE COMMONWEALTH OF PUERTO RICO, portion III.iii" (PDF). U.S. Supreme Court. December 2, 2008. Retrieved August 8, 2018.

- ^ https://thehill.com/opinion/judiciary/371266-the-contradictions-of-americas-unincorporated-territory The Hill. The Contradictions of America's Unincorporated Territory. Andres L. Cordova. January 29, 2018. Retrieved July 4, 2019.

- ^ a b c "Rassmussen v. U.S". U.S. Supreme Court. April 10, 1905. Retrieved October 4, 2017 – via FindLaw.

- ^ Juan R. Torruella (2007). "The Insular Cases: The Establishment of a Regime of Political Apartheid" (PDF). pp. 318–319. Retrieved February 7, 2010.

- ^ "Dorr v. U.S". U.S. Supreme Court. May 31, 1904. Retrieved October 4, 2017 – via FindLaw.

- ^ a b c "Downes v. Bidwell". U.S. Supreme Court. May 27, 1901. Retrieved October 4, 2017 – via FindLaw.

- ^ Zaide, Sonia M. (1994). The Philippines: A Unique Nation. All-Nations Publishing Co., Inc. p. 279. ISBN 978-9716420715. Retrieved October 20, 2011.