The Tempest

Title page of the part in the First Folio. | |

| Editors | Edward Blount and Isaac Jaggard |

|---|---|

| Author | William Shakespeare |

| Illustrator | London |

| Country | England |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Shakespearean comedy Tragicomedy |

The Tempest is a play by William Shakespeare, probably written in 1610–1611, and thought to be one of the last plays that Shakespeare wrote alone. After the first scene, which takes place on a ship at sea during a tempest, the rest of the story is set on a remote island, where the sorcerer Prospero, a complex and contradictory character, lives with his daughter Miranda, and his two servants—Caliban, a savage monster figure, and Ariel, an airy spirit. The play contains music and songs that evoke the spirit of enchantment on the island. It explores many themes, including magic, betrayal, revenge, and family. In Act IV, a wedding masque serves as a play-within-the play, and contributes spectacle, allegory, and elevated language.

Though The Tempest is listed in the First Folio as the first of Shakespeare's comedies, it deals with both tragic and comic themes, and modern criticism has created a category of romance for this and others of Shakespeare's late plays. The Tempest has been put to varied interpretations—from those that see it as a fable of art and creation, with Prospero representing Shakespeare, and Prospero's renunciation of magic signaling Shakespeare's farewell to the stage, to interpretations that consider it an allegory of Europeans colonizing foreign lands.

Characters[edit]

- Prospero – the rightful Duke of Milan

- Miranda – daughter to Prospero

- Ariel – a spirit in service to Prospero

- Caliban – a servant of Prospero and a savage monster

- Alonso – King of Naples

- Sebastian – Alonso's brother

- Antonio – Prospero's brother, the usurping Duke of Milan

- Ferdinand – Alonso's son

- Gonzalo – an honest old councillor

- Adrian – a lord serving under Alonso

- Francisco – a lord serving under Alonso

- Trinculo – the King's jester

- Stephano – the King's drunken butler

- Juno – the Roman goddess of marriage

- Ceres – Roman goddess of agriculture

- Iris – Greek goddess of the sea and sky

- Master – master of the ship

- Mariners

- Boatswain – servant of the master

- Nymphs, Reapers

Plot[edit]

A ship is caught in a powerful storm, there is terror and confusion on board, and the vessel is shipwrecked. But the storm is a magical creation carried out by the spirit Ariel, and caused by the magic of Prospero, who was the Duke of Milan, before his dukedom was usurped and taken from him by his brother Antonio (aided by Alonso, the King of Naples). That was twelve years ago, when he and his young daughter, Miranda, were set adrift on the sea, and eventually stranded on an island. Among those on board the shipwreck are Antonio and Alonso. Also on the ship are Alonso's brother (Sebastian), son (Ferdinand), and "trusted counsellor", Gonzalo. Prospero plots to reverse what was done to him twelve years ago, and regain his office. Using magic he separates the shipwreck survivors into groups on the island:

- Ferdinand, who is found by Prospero and Miranda. It is part of Prospero's plan to encourage a romantic relationship between Ferdinand and Miranda; and they do fall in love.

- Trinculo, the king's jester, and Stephano, the king's drunken butler; who are found by Caliban, a monstrous figure who had been living on the island before Prospero arrived, and who Prospero, adopted, raised and enslaved. These three will raise an unsuccessful coup against Prospero, acting as the play's 'comic relief' by doing so.

- Alonso, Sebastian, Antonio, Gonzalo, and two attendant lords (Adrian and Francisco). Antonio and Sebastian conspire to kill Alonso and Gonzalo so Sebastian can become King; at Prospero's command Ariel thwarts this conspiracy. Later in the play, Ariel, in the guise of a Harpy, confronts the three nobles (Antonio, Alonso and Sebastian), causing them to flee in guilt for their crimes against Prospero and each other.

- The ship's captain and boatswain, along with the other sailors, are asleep until the final act.

Prospero betroths Miranda to marry Ferdinand, and instructs Ariel to bring some other spirits and produce a masque. The masque will feature classical goddesses, Juno, Ceres, and Iris, and will bless and celebrate the betrothal. The masque will also instruct the young couple on marriage, and on the value of chastity until then.

The masque is suddenly interrupted when Prospero realizes he had forgotten the plot against his life. He orders Ariel to deal with this. Caliban, Trinculo, and Stephano are chased off into the swamps by goblins in the shape of hounds. Prospero vows that once he achieves his goals, he will set Ariel free, and abandon his magic, saying:

- I’ll break my staff,

- Bury it certain fathoms in the earth,

- And deeper than did ever plummet sound

- I’ll drown my book.[1]

Ariel brings on Alonso, Antonio and Sebastian. Prospero forgives all three, and raises the threat to Antonio and Sebastian that he could blackmail them, though he won't. Prospero's former title, Duke of Milan, is restored. Ariel fetches the sailors from the ship; then Caliban, Trinculo, and Stephano. Caliban, seemingly filled with regret, promises to be good. Stephano and Trinculo are ridiculed and sent away in shame by Prospero. Before the reunited group (all the noble characters plus Miranda and Prospero) leaves the island, Ariel is told to provide good weather to guide the king's ship back to the royal fleet and then to Naples, where Ferdinand and Miranda will be married. After this, Ariel is set free. In the epilogue, Prospero requests that the audience set him free—with their applause.

The masque[edit]

The Tempest begins with the spectacle of a storm-tossed ship at sea, and later there is a second spectacle—the masque. A masque in Renaissance England was a festive courtly entertainment that offered music, dance, elaborate sets, costumes, and drama. Often a masque would begin with an "anti-masque", that showed a disordered scene of satyrs, for example, singing and dancing wildly. The anti-masque would then be dramatically dispersed by the spectacular arrival of the masque proper in a demonstration of chaos and vice being swept away by glorious civilization. In Shakespeare's play, the storm in scene one functions as the anti-masque for the masque proper in act four.[2][3][4]

The masque in The Tempest is not an actual masque, it is an analogous scene intended to mimic and evoke a masque, while serving the narrative of the drama that contains it. The masque is a culmination of the primary action in The Tempest: Prospero's intention to not only seek revenge on his usurpers, but to regain his rightful position as Duke of Milan. Most important to his plot to regain his power and position is to marry Miranda to Ferdinand, heir to the King of Naples. This marriage will secure Prospero's position by securing his legacy. The chastity of the bride is considered essential and greatly valued in royal lineages. This is true not only in Prospero's plot, but also notably in the court of the virgin queen, Elizabeth. Sir Walter Raleigh had in fact named one of the new world colonies "Virginia" after his monarch's chastity. It was also understood by James, king when The Tempest was first produced, as he arranged political marriages for his grandchildren. What could possibly go wrong with Prospero's plans for his daughter is nature: the fact that Miranda is a young woman who has just arrived at a time in her life when natural attractions among young people become powerful. One threat is the 24-year-old Caliban, who has spoken of his desire to rape Miranda, and "people this isle with Calibans",[5] and who has also offered Miranda's body to a drunken Stephano.[6] Another threat is represented by the young couple themselves, who might succumb to each other prematurely. Prospero says:

- Look though be true. Do not give dalliance

- Too much the rein. The strongest oaths are straw

- To th'fire i'th'blood. Be more abstemious

- Or else good night your vow![7]

Prospero, keenly aware of all this, feels the need to teach Miranda—an intention he first stated in act one.[8] The need to teach Miranda is what inspires Prospero in act four to create the masque,[9] and the "value of chastity" is a primary lesson being taught by the masque along with having a happy marriage.[10][11][12]

Date and sources[edit]

Date[edit]

It is not known for certain exactly when The Tempest was written, but evidence supports the idea that it was probably composed sometime between late 1610 to mid-1611. It is considered one of the last plays that Shakespeare wrote alone.[13][14] Evidence supports composition perhaps occurring before, after, or at the same time as The Winter's Tale.[13] Edward Blount entered The Tempest into the Stationers' Register on 8 November 1623. It was one of 16 Shakespearean plays that Blount registered on that date.[15]

Contemporary sources[edit]

There is no obvious single origin for the plot of The Tempest; it appears to have been created with several sources contributing.[16] Since source scholarship began in the eighteenth century, researchers have suggested passages from "Naufragium" ("The Shipwreck"), one of the colloquies in Erasmus's Colloquia Familiaria (1518),[a] and Richard Eden's 1555 translation of Peter Martyr's De orbo novo (1530).[18]

William Strachey's A True Reportory of the Wracke and Redemption of Sir Thomas Gates, Knight, an eye witness report of the real-life shipwreck of the Sea Venture in 1609 on the island of Bermuda while sailing toward Virginia, is considered a primary source for the opening scene, as well as a few other references in the play to conspiracies and retributions.[19] Although not published until 1625, Strachey's report, one of several describing the incident, is dated 15 July 1610, and it is thought that Shakespeare must have seen it in manuscript sometime during that year. E.K. Chambers identified the True Reportory as Shakespeare's "main authority" for The Tempest.[20] Regarding the influence of Strachey in the play, Kenneth Muir says that although "[t]here is little doubt that Shakespeare had read ... William Strachey's True Reportory" and other accounts, "[t]he extent of the verbal echoes of [the Bermuda] pamphlets has, I think, been exaggerated. There is hardly a shipwreck in history or fiction which does not mention splitting, in which the ship is not lightened of its cargo, in which the passengers do not give themselves up for lost, in which north winds are not sharp, and in which no one gets to shore by clinging to wreckage", and goes on to say that "Strachey's account of the shipwreck is blended with memories of Saint Paul's—in which too not a hair perished—and with Erasmus' colloquy."[21]

Another Sea Venture survivor, Sylvester Jourdain, published his account, A Discovery of The Barmudas dated 13 October 1610; Edmond Malone argues for the 1610–11 date on the account by Jourdain and the Virginia Council of London's A True Declaration of the Estate of the Colonie in Virginia dated 8 November 1610.[22]

Michel de Montaigne's essay "Of the Caniballes" is considered a source for Gonzalo's utopian speculations in Act II, scene 1, and possibly for other lines that refer to differences between cultures.[19]

A poem entitled Pimlyco; or, Runne Red-Cap was published as a pamphlet in 1609. It was written in praise of a tavern in Hoxton. The poem includes extensive quotations of an earlier (1568) poem, The Tunning of Elynor Rymming, by John Skelton. The pamphlet contains a pastoral story of a voyage to an island. There is no evidence that Shakespeare read this pamphlet, was aware of it, or had used it. However, the poem may be useful as a source to researchers regarding how such themes and stories were being interpreted and told in London near to the time The Tempest was written.[23]

Other sources[edit]

The Tempest may take its overall structure from traditional Italian commedia dell'arte, which sometimes featured a magus and his daughter, their supernatural attendants, and a number of rustics. The commedia often featured a clown known as Arlecchino (or his predecessor, Zanni) and his partner Brighella, who bear a striking resemblance to Stephano and Trinculo; a lecherous Neapolitan hunchback who corresponds to Caliban; and the clever and beautiful Isabella, whose wealthy and manipulative father, Pantalone, constantly seeks a suitor for her, thus mirroring the relationship between Miranda and Prospero.[24]

Gonzalo's description of his ideal society (2.1.148–157, 160–165) thematically and verbally echoes Montaigne's essay Of the Canibales, translated into English in a version published by John Florio in 1603. Montaigne praises the society of the Caribbean natives: "It is a nation ... that hath no kinde of traffike, no knowledge of Letters, no intelligence of numbers, no name of magistrate, nor of politike superioritie; no use of service, of riches, or of poverty; no contracts, no successions, no dividences, no occupation but idle; no respect of kinred, but common, no apparrell but natural, no manuring of lands, no use of wine, corne, or mettle. The very words that import lying, falsehood, treason, dissimulation, covetousnes, envie, detraction, and pardon, were never heard of amongst them."[25]

A source for Prospero's speech in act five, in which he bids farewell to magic (5.1.33–57) is an invocation by the sorceress Medea found in Ovid's poem Metamorphoses. Medea calls out:

- Ye airs and winds; ye elves of hills, of brooks, of woods alone,

- Of standing lakes, and of the night, approach ye every one,

- Through help of whom (the crooked banks much wondering at the thing)

- I have compelled streams to run clean backward to their spring. (Ovid, 7.265–268)

Shakespeare's Prospero begins his invocation:

- Ye elves of hills, brooks, standing lakes and groves,

- And ye that on the sands with printless foot

- Do chase the ebbing Neptune, and do fly him

- When he comes back . . . (5.1.33–36)[26]

Text[edit]

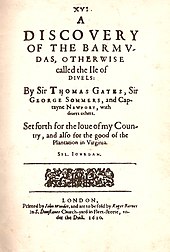

The Tempest first appeared in print in 1623 in the collection of thirty-six of Shakespeare's plays entitled, Mr. William Shakespeare's Comedies, Histories, & Tragedies; Published according to the True and Original Copies, which is known as the First Folio. The plays, including The Tempest, were gathered and edited by John Heminges and Henry Condell.[27]

A handwritten manuscript of The Tempest was prepared by Ralph Crane, a scrivener employed by the King's Men. A scrivener is one who has a talent and is practiced at using a quill pen and ink to create legible manuscripts. Crane probably copied from Shakespeare's rough draft, and based his style on Ben Jonson's Folio of 1616. Crane is thought to have neatened texts, edited the divisions of acts and scenes, and sometimes added his own improvements. He was fond of joining words with hyphens, and using elisions with apostrophes, for example by changing "with the king" to read: "w’th’ King".[28] The elaborate stage directions in The Tempest may have been due to Crane; they provide evidence regarding how the play was staged by the King's Company.[29]

The entire First Folio project was delivered to the blind printer, William Jaggard, and printing began in 1622. The Tempest is the first play in the publication. It was proofread and printed with special care; it is the most well-printed and the cleanest text of the thirty-six plays. To do the work of setting the type in the printing press, three compositors were used for The Tempest. In the 1960s, a landmark bibliographic study of the First Folio was accomplished by Charlton Hinman. Based on distinctive quirks in the printed words on the page, the study was able to individuate the compositors, and reveal that three compositors worked on The Tempest, who are known as Compositor B, C, and F. Compositor B worked on The Tempest's first page as well as six other pages. He was an experienced journeyman in Jaggard's printshop, who occasionally could be careless. He also was fond of dashes and colons, where modern editions use commas. In his role, he may have had a responsibility for the entire First Folio. The other two, Compositors C and F, worked full-time and were experienced printers.[30]

At the time, spelling and punctuation was not standardized and will vary from page to page, because each compositor had their individual preferences and styles. There is evidence that the press run was stopped at least four times, which allowed proofreading and corrections. However, a page with an error would not be discarded, so pages late in any given press run would be the most accurate, and each of the final printed folios may vary in this regard. This is the common practice at the time. There is also an instance of a letter (a metal sort or a type) being damaged (possibly) during the course of a run and changing the meaning of a word: After the masque Ferdinand says,

- Let me live here ever!

- So rare a wondered father and a wise

- Makes this place paradise! (4.1.122–124)

The word "wise" at the end of line 123 was printed with the traditional long "s" that resembles an "f". But in 1978 it was suggested that during the press run, a small piece of the crossbar on the type had broken off, and the word should be "wife". Modern editors have not come to an agreement—Oxford says "wife", Arden says "wise".[31][32][33]

Themes and motifs[edit]

The Theatre[edit]

|

|---|

The Tempest is explicitly concerned with its own nature as a play, frequently drawing links between Prospero's art and theatrical illusion; the shipwreck was a spectacle that Ariel performed, while Antonio and Sebastian are cast in a troupe to act.[35] Prospero may even refer to the Globe Theatre when he describes the whole world as an illusion: "the great globe ... shall dissolve ... like this insubstantial pageant".[36] Ariel frequently disguises himself as figures from Classical mythology, for example a nymph, a harpy, and Ceres, acting as the latter in a masque and anti-masque that Prospero creates.[37]

Thomas Campbell in 1838 was the first to consider that Prospero was meant to partially represent Shakespeare, but then abandoned that idea when he came to believe that The Tempest was an early play.[38]

Magic[edit]

Prospero is a magician, whose magic is a beneficial "white magic". Prospero learned his magic by studying in his books about nature, and he uses magic to achieve what he considers positive outcomes. Shakespeare uses Caliban to indicate the opposite—evil black magic. Caliban's mother, Sycorax, who does not appear, represents the horrors that were stirring at this time in England and elsewhere regarding witchcraft and black magic. The unseen character is said to be from 'Argier,' defined by geographer Mohamed S. E. Madiou as "a 16th and 17th century older English-based exonym for both the 16th and 17th c. capital and state of ‘Algiers’ (Argier/Argier)."[39] Magic was taken seriously and studied by serious philosophers, notably the German Henricus Cornelius Agrippa, who in 1533 published in three volumes his De Occulta Philosophia, which summarized work done by Italian scholars on the topic of magic. Agrippa's work influenced John Dee (1527–1608), an Englishman, who, like Prospero, had a large collection of books on the occult, as well as on science and philosophy. It was a dangerous time to philosophize about magic—Giordano Bruno for example was burned at the stake in Italy in 1600—just a few years before The Tempest was written.[40]

Prospero uses magic grounded in science and reality—the kind that was studied by Agrippa and Dee. Prospero studied and gradually was able to develop the kind of power represented by Ariel, which extended his abilities. Sycorax's magic was not capable of something like Ariel: "Ariel is a spirit too delicate to act her earthy and abhored commands."[41] Prospero's rational goodness enables him to control Ariel, where Sycorax can only trap him in a tree.[42] Sycorax's magic is described as destructive and terrible, where Prospero's is said to be wondrous and beautiful. Prospero seeks to set things right in his world through his magic, and once that is done, he renounces it, setting Ariel free.[40]

What Prospero is trying to do with magic is essential to The Tempest; it is the unity of action. It is referred to it as Prospero's project in act two when Ariel stops an attempted assassination:

- My master through his art forsees the danger

- That you, his friend, are in, and sends me forth—

- For else his project dies—to keep them living![43]

At the start of act five Prospero says:

- Now does my project gather to a head[44]

Prospero seems to know precisely what he wants. Beginning with the tempest at the top of the play, his project is laid out in a series of steps. "Bountiful fortune"[45] has given him a chance to affect his destiny, and that of his county and family.[46]

His plan is to do all he can to reverse what was done twelve years ago when he was usurped: First he will use a tempest to cause certain persons to fear his great powers, then when all survived unscathed, he will separate those who lived through the tempest into different groups. These separations will let him deal with each group differently. Then Prospero's plan is to lead Ferdinand to Miranda, having prepared them both for their meeting. What is beyond his magical powers is to cause them to fall in love. But they do. The next stages for the couple will be a testing. To help things along he magically makes the others fall into a sleep. The masque which is to educate and prepare the couple is next. But then his plans begin to go off the tracks when the masque is interrupted.[47] Next Prospero confronts those who usurped him, he demands his dukedom and a “brave new world”[48] by the merging of Milan and Naples through the marriage of Ferdinand and Miranda.[49]

Prospero's magic hasn't worked on Sebastian and Antonio, who are not penitent. Prospero then deals with Antonio, not with magic, but with something more mundane—blackmail.[50] This failure of magic is significant, and critics disagree regarding what it means: Jan Kott considers it a disillusionment for both Prospero and for the author.[51] E. M. W. Tillyard plays it down as a minor disappointment. Some critics consider Sebastian and Antonio clownish and not a real threat. Stephen Orgel blames Prospero for causing the problem by forgetting about Sebastian and Antonio, which may introduce a theme of Prospero's encroaching dotage.[52] David Hirst suggests that the failure of Prospero's magic may have a deeper explanation: He suggests that Prospero's magic has had no effect at all on certain things (like Caliban), that Prospero is idealistic and not realistic, and that his magic makes Prospero like a god, but it also makes him other than human, which explains why Prospero seems impatient and ill-suited to deal with his daughter, for example, when issues call on his humanity, not his magic. It explains his dissatisfaction with the “real world”, which is what cost him his dukedom, for example, in the first place. In the end Prospero is learning the value of being human.[49]

Criticism and interpretation[edit]

Genre[edit]

The story draws heavily on the tradition of the romance, a fictitious narrative set far away from ordinary life. Romances were typically based around themes such as the supernatural, wandering, exploration and discovery. They were often set in coastal regions, and typically featured exotic, fantastical locations and themes of transgression and redemption, loss and retrieval, exile and reunion. As a result, while The Tempest was originally listed as a comedy in the First Folio of Shakespeare's plays, subsequent editors have chosen to give it the more specific label of Shakespearean romance. Like the other romances, the play was influenced by the then-new genre of tragicomedy, introduced by John Fletcher in the first decade of the 17th century and developed in the Beaumont and Fletcher collaborations, as well as by the explosion of development of the courtly masque form by such as Ben Jonson and Inigo Jones at the same time.[53]

Dramatic structure[edit]

Like The Comedy of Errors, The Tempest roughly adheres to the unities of time, place, and action.[54] Shakespeare's other plays rarely respected the three unities, taking place in separate locations miles apart and over several days or even years.[55] The play's events unfold in real time before the audience, Prospero even declaring in the last act that everything has happened in, more or less, three hours.[56][57] All action is unified into one basic plot: Prospero's struggle to regain his dukedom; it is also confined to one place, a fictional island, which many scholars agree is meant to be located in the Mediterranean Sea.[58] Another reading suggests that it takes place in the New World, as some parts read like records of English and Spanish conquest in the Americas.[59] Still others argue that the Island can represent any land that has been colonised.[60]

In the denouement of the play, Prospero enters into a parabasis (a direct address to the audience). In his book Back and Forth the poet and literary critic Siddhartha Bose argues that Prospero's epilogue creates a "permanent parabasis" which is “the condition of [Schlegelian] Romantic Irony”.[61] Prospero, and by extension Shakespeare, turns his absolution over to the audience. The liberation and atonement Prospero 'gives' to Ariel and Caliban is also handed over to the audience. However, just as Prospero derives his power by "creating the language with which the other characters are able to speak about their experiences",[62] so too the mechanics and customs of theatre limit the audience's understanding of itself and its relationship to the play and to reality. Four centuries after original productions of the play audiences are still clapping at the end of The Tempest, rewarding Prospero for recreating the European hegemony. One need not change the text of The Tempest for feminist and anti-colonial reproductions. All that is needed is a different kind of audience, one that is aware of itself and its agency.

Postcolonial[edit]

In Shakespeare's day, much of the world was still being colonized by European merchants and settlers, and stories were coming back from the Americas, with myths about the Cannibals of the Caribbean, faraway Edens, and distant tropical Utopias. With the character Caliban (whose name is almost an anagram of Cannibal and also resembles "Cariban", the term then used for natives in the West Indies), it has been suggested that Shakespeare may be offering an in-depth discussion of the morality of colonialism. Different views of this are found in the play, with examples including Gonzalo's Utopia, Prospero's enslavement of Caliban, and Caliban's subsequent resentment. Postcolonial scholars have argued that Caliban is also shown as one of the most natural characters in the play, being very much in touch with the natural world (and modern audiences have come to view him as far nobler than his two Old World friends, Stephano and Trinculo, although the original intent of the author may have been different). There is evidence that Shakespeare drew on Montaigne's essay Of Cannibals—which discusses the values of societies insulated from European influences—while writing The Tempest.[63]

Beginning in about 1950, with the publication of Psychology of Colonization by Octave Mannoni, Postcolonial theorists have increasingly appropriated The Tempest and reinterpreted it in light of postcolonial theory. This new way of looking at the text explored the effect of the "coloniser" (Prospero) on the "colonised" (Ariel and Caliban). Although Ariel is often overlooked in these debates in favour of the more intriguing Caliban, he is nonetheless an essential component of them.[64] The French writer Aimé Césaire, in his play Une Tempête sets The Tempest in Haiti, portraying Ariel as a mulatto who, unlike the more rebellious Caliban, feels that negotiation and partnership is the way to freedom from the colonisers. Fernandez Retamar sets his version of the play in Cuba, and portrays Ariel as a wealthy Cuban (in comparison to the lower-class Caliban) who also must choose between rebellion or negotiation.[65] It has also been argued that Ariel, and not Caliban or Prospero, is the rightful owner of the island.[66] Michelle Cliff, a Jamaican author, has said that she tries to combine Caliban and Ariel within herself to create a way of writing that represents her culture better. Such use of Ariel in postcolonial thought is far from uncommon; the spirit is even the namesake of a scholarly journal covering post-colonial criticism.[64]

Feminist[edit]

Feminist interpretations of The Tempest consider the play in terms of gender roles and relationships among the characters on stage, and consider how concepts of gender are constructed and presented by the text, and explore the supporting consciousnesses and ideologies, all with an awareness of imbalances and injustices.[67] Two early feminist interpretations of The Tempest are included in Anna Jameson's Shakespeare’s Heroines (1832) and Mary Clarke's The Girlhood of Shakespeare’s Heroines (1851).[68][69]

The Tempest is a play created in a male dominated culture and society, a gender imbalance the play explores metaphorically by having only one major female role, Miranda. Miranda is fifteen, intelligent, naive, and beautiful. The only humans she has ever encountered in her life are male. Prospero sees himself as her primary teacher, and asks if she can remember a time before they arrived to the island—he assumes that she cannot. When Miranda has a memory of "four or five women" tending to her younger self (1.2.44–47), it disturbs Prospero, who prefers to portray himself as her only teacher, and the absolute source of her own history—anything before his teachings in Miranda's mind should be a dark "abysm", according to him. (1.2.48–50) The "four or five women" Miranda remembers may symbolize the young girl's desire for something other than only men.[70][71]

Other women, such as Caliban's mother Sycorax, Miranda's mother and Alonso's daughter Claribel, are only mentioned. Because of the small role women play in the story in comparison to other Shakespeare plays, The Tempest has attracted much feminist criticism. Miranda is typically viewed as being completely deprived of freedom by her father. Her only duty in his eyes is to remain chaste. Ann Thompson argues that Miranda, in a manner typical of women in a colonial atmosphere, has completely internalised the patriarchal order of things, thinking of herself as subordinate to her father.[72]

Most of what is said about Sycorax is said by Prospero, who has never met Sycorax—what he knows of her he learned from Ariel. When Miranda asks Prospero, "Sir, are you not my father?”, Prospero responds,

- Thy mother was a piece of virtue, and

- She said thou was my daughter.[73]

This surprising answer has been difficult for those interpretations that portray their relationship simply as a lordly father to an innocent daughter, and the exchange has at times been cut in performance. A similar example occurs when Prospero, enraged, raises a question of the parentage of his brother, and Miranda defends Prospero's mother:

Research and genetic modification[edit]

The book 'Brave New World' by Aldous Huxley references The Tempest in the title, and explores genetically modified citizens and the subsequent social effects.[76] The novel and the phrase from The Tempest 'brave new world' has itself since been associated with public debate about humankind's understanding and use of genetic modification, in particular with regards to humans.[77]

Performance history[edit]

Shakespeare's day[edit]

A record exists of a performance of The Tempest on 1 November 1611 by the King's Men before James I and the English royal court at Whitehall Palace on Hallowmas night.[78] The play was one of the six Shakespearean plays (and eight others for a total of 14) acted at court during the winter of 1612–13 as part of the festivities surrounding the marriage of Princess Elizabeth with Frederick V, the Elector of the Palatinate of the Rhine.[79] There is no further public performance recorded prior to the Restoration; but in his 1669 preface to the Dryden/Davenant version, John Dryden states that The Tempest had been performed at the Blackfriars Theatre.[80] Careful consideration of stage directions within the play supports this, strongly suggesting that the play was written with Blackfriars Theatre rather than the Globe Theatre in mind.[81][82]

Restoration and 18th century[edit]

Adaptations of the play, not Shakespeare's original, dominated the performance history of The Tempest from the English Restoration until the mid-19th century.[83] All theatres were closed down by the puritan government during the English Interregnum. Upon the restoration of the monarchy in 1660, two patent companies—the King's Company and the Duke's Company—were established, and the existing theatrical repertoire divided between them. Sir William Davenant's Duke's Company had the rights to perform The Tempest.[84] In 1667 Davenant and John Dryden made heavy cuts and adapted it as The Tempest, or The Enchanted Island. They tried to appeal to upper-class audiences by emphasising royalist political and social ideals: monarchy is the natural form of government; patriarchal authority decisive in education and marriage; and patrilineality preeminent in inheritance and ownership of property.[83] They also added characters and plotlines: Miranda has a sister, named Dorinda; Caliban also has a sister, named Sycorax. As a parallel to Shakespeare's Miranda/Ferdinand plot, Prospero has a foster-son, Hippolito, who has never set eyes on a woman.[85] Hippolito was a popular breeches role, a man played by a woman, popular with Restoration theatre management for the opportunity to reveal actresses' legs.[86] Scholar Michael Dobson has described The Tempest, or The Enchanted Island by Dryden and Davenant as "the most frequently revived play of the entire Restoration" and as establishing the importance of enhanced and additional roles for women.[87]

In 1674, Thomas Shadwell re-adapted Dryden and Davenant as an opera of the same name, usually meaning a play with sections that were to be sung or danced. Restoration playgoers appear to have regarded the Dryden/Davenant/Shadwell version as Shakespeare's: Samuel Pepys, for example, described it as "an old play of Shakespeares" in his diary. The opera was extremely popular, and "full of so good variety, that I cannot be more pleased almost in a comedy" according to Pepys.[88] Prospero in this version is very different from Shakespeare's: Eckhard Auberlen describes him as "reduced to the status of a Polonius-like overbusy father, intent on protecting the chastity of his two sexually naive daughters while planning advantageous dynastic marriages for them."[89] The operatic Enchanted Island was successful enough to provoke a parody, The Mock Tempest, or The Enchanted Castle, written by Thomas Duffett for the King's Company in 1675. It opened with what appeared to be a tempest, but turns out to be a riot in a brothel.[90]

In the early 18th century, the Dryden/Davenant/Shadwell version dominated the stage. Ariel was—with two exceptions—played by a woman, and invariably by a graceful dancer and superb singer. Caliban was a comedian's role, played by actors "known for their awkward figures". In 1756, David Garrick staged another operatic version, a "three-act extravaganza" with music by John Christopher Smith.[91]

The Tempest was one of the staples of the repertoire of Romantic Era theatres. John Philip Kemble produced an acting version which was closer to Shakespeare's original, but nevertheless retained Dorinda and Hippolito.[91] Kemble was much-mocked for his insistence on archaic pronunciation of Shakespeare's texts, including "aitches" for "aches". It was said that spectators "packed the pit, just to enjoy hissing Kemble's delivery of 'I'll rack thee with old cramps, / Fill all they bones with aches'."[92][93] The actor-managers of the Romantic Era established the fashion for opulence in sets and costumes which would dominate Shakespeare performances until the late 19th century: Kemble's Dorinda and Miranda, for example, were played "in white ornamented with spotted furs".[94]

In 1757, a year after the debut of his operatic version, David Garrick produced a heavily cut performance of Shakespeare's script at Drury Lane, and it was revived, profitably, throughout the century.[91]

19th century[edit]

It was not until William Charles Macready's influential production in 1838 that Shakespeare's text established its primacy over the adapted and operatic versions which had been popular for most of the previous two centuries. The performance was particularly admired for George Bennett's performance as Caliban; it was described by Patrick MacDonnell—in his An Essay on the Play of The Tempest published in 1840—as "maintaining in his mind, a strong resistance to that tyranny, which held him in the thraldom of slavery".[95]

The Victorian era marked the height of the movement which would later be described as "pictorial": based on lavish sets and visual spectacle, heavily cut texts making room for lengthy scene-changes, and elaborate stage effects.[96] In Charles Kean's 1857 production of The Tempest, Ariel was several times seen to descend in a ball of fire.[97] The hundred and forty stagehands supposedly employed on this production were described by the Literary Gazette as "unseen ... but alas never unheard". Hans Christian Andersen also saw this production and described Ariel as "isolated by the electric ray", referring to the effect of a carbon arc lamp directed at the actress playing the role.[98] The next generation of producers, which included William Poel and Harley Granville-Barker, returned to a leaner and more text-based style.[99]

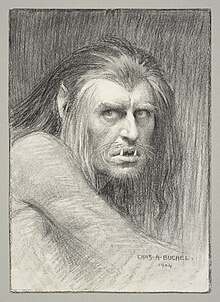

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Caliban, not Prospero, was perceived as the star act of The Tempest, and was the role which the actor-managers chose for themselves. Frank Benson researched the role by viewing monkeys and baboons at the zoo; on stage, he hung upside-down from a tree and gibbered.[100]

20th century and beyond[edit]

Continuing the late-19th-century tradition, in 1904 Herbert Beerbohm Tree wore fur and seaweed to play Caliban, with waist-length hair and apelike bearing, suggestive of a primitive part-animal part-human stage of evolution.[100] This "missing link" portrayal of Caliban became the norm in productions until Roger Livesey, in 1934, was the first actor to play the role with black makeup. In 1945 Canada Lee played the role at the Theatre Guild in New York, establishing a tradition of black actors taking the role, including Earle Hyman in 1960 and James Earl Jones in 1962.[101]

In 1916, Percy MacKaye presented a community masque, Caliban by the Yellow Sands, at the Lewisohn Stadium in New York. Amidst a huge cast of dancers and masquers, the pageant centres on the rebellious nature of Caliban but ends with his plea for more knowledge ("I yearn to build, to be thine Artist / And 'stablish this thine Earth among the stars- / Beautiful!") followed by Shakespeare, as a character, reciting Prospero's "Our revels now are ended" speech.[102][103]

John Gielgud played Prospero numerous times, and is, according to Douglas Brode, "universally heralded as … [the 20th] century's greatest stage Prospero".[104] His first appearance in the role was in 1930: he wore a turban, later confessing that he intended to look like Dante.[101] He played the role in three more stage productions, lastly at the Royal National Theatre in 1974.[105] Derek Jacobi's Prospero for The Old Vic in 2003 was praised for his portrayal of isolation and pain in ageing.[106]

Peter Brook directed an experimental production at the Round House in 1968, in which the text was "almost wholly abandoned" in favour of mime. According to Margaret Croydon's review, Sycorax was "portrayed by an enormous woman able to expand her face and body to still larger proportions—a fantastic emblem of the grotesque ... [who] suddenly ... gives a horrendous yell, and Caliban, with black sweater over his head, emerges from between her legs: Evil is born."[107]

In spite of the existing tradition of a black actor playing Caliban opposite a white Prospero, colonial interpretations of the play did not find their way onto the stage until the 1970s.[108] Performances in England directed by Jonathan Miller and by Clifford Williams explicitly portrayed Prospero as coloniser. Miller's production was described, by David Hirst, as depicting "the tragic and inevitable disintegration of a more primitive culture as the result of European invasion and colonisation".[109][110] Miller developed this approach in his 1988 production at the Old Vic in London, starring Max von Sydow as Prospero. This used a mixed cast made up of white actors as the humans and black actors playing the spirits and creatures of the island. According to Michael Billington, "von Sydow's Prospero became a white overlord manipulating a mutinous black Caliban and a collaborative Ariel keenly mimicking the gestures of the island's invaders. The colonial metaphor was pushed through to its logical conclusion so that finally Ariel gathered up the pieces of Prospero's abandoned staff and, watched by awe-struck tribesmen, fitted them back together to hold his wand of office aloft before an immobilised Caliban. The Tempest suddenly acquired a new political dimension unforeseen by Shakespeare."[111]

Psychoanalytic interpretations have proved more difficult to depict on stage.[110] Gerald Freedman's production at the American Shakespeare Theatre in 1979 and Ron Daniels' Royal Shakespeare Company production in 1982 both attempted to depict Ariel and Caliban as opposing aspects of Prospero's psyche. However neither was regarded as wholly successful: Shakespeare Quarterly, reviewing Freedman's production, commented, "Mr. Freedman did nothing on stage to make such a notion clear to any audience that had not heard of it before."[112][113]

In 1988, John Wood played Prospero for the RSC, emphasising the character's human complexity, in a performance a reviewer described as "a demented stage manager on a theatrical island suspended between smouldering rage at his usurpation and unbridled glee at his alternative ethereal power".[114][115]

Japanese theatre styles have been applied to The Tempest. In 1988 and again in 1992 Yukio Ninagawa brought his version of The Tempest to the UK. It was staged as a rehearsal of a Noh drama, with a traditional Noh theatre at the back of the stage, but also using elements which were at odds with Noh conventions. In 1992, Minoru Fujita presented a Bunraku (Japanese puppet) version in Osaka and at the Tokyo Globe.[116]

Sam Mendes directed a 1993 RSC production in which Simon Russell Beale's Ariel was openly resentful of the control exercised by Alec McCowen's Prospero. Controversially, in the early performances of the run, Ariel spat at Prospero, once granted his freedom.[117] An entirely different effect was achieved by George C. Wolfe in the outdoor New York Shakespeare Festival production of 1995, where the casting of Aunjanue Ellis as Ariel opposite Patrick Stewart's Prospero charged the production with erotic tensions. Productions in the late 20th-century have gradually increased the focus placed on sexual tensions between the characters, including Prospero/Miranda, Prospero/Ariel, Miranda/Caliban, Miranda/Ferdinand and Caliban/Trinculo.[118]

The Tempest was performed at the Globe Theatre in 2000 with Vanessa Redgrave as Prospero, playing the role as neither male nor female, but with "authority, humanity and humour ... a watchful parent to both Miranda and Ariel."[119] While the audience respected Prospero, Jasper Britton's Caliban "was their man" (in Peter Thomson's words), in spite of the fact that he spat fish at the groundlings, and singled some of them out for humiliating encounters.[120] By the end of 2005, BBC Radio had aired 21 productions of The Tempest, more than any other play by Shakespeare.[121]

In 2016 The Tempest was produced by the Royal Shakespeare Company. Directed by Gregory Doran, and featuring Simon Russell Beale, the RSC's version used performance capture to project Ariel in real time on stage. The performance was in collaboration with The Imaginarium and Intel, and featured "some gorgeous [and] some interesting"[122] use of light, special effects, and set design.[122]

Music[edit]

The Tempest has more music than any other Shakespeare play, and has proved more popular as a subject for composers than most of Shakespeare's plays. Scholar Julie Sanders ascribes this to the "perceived 'musicality' or lyricism" of the play.[123]

Two settings of songs from The Tempest which may have been used in performances during Shakespeare's lifetime have survived. These are "Full Fathom Five" and "Where The Bee Sucks There Suck I" in the 1659 publication Cheerful Ayres or Ballads, in which they are attributed to Robert Johnson, who regularly composed for the King's Men.[124] It has been common throughout the history of the play for the producers to commission contemporary settings of these two songs, and also of "Come Unto These Yellow Sands".[125]

The Tempest has also influenced songs written in the folk and hippie traditions: for example, versions of "Full Fathom Five" were recorded by Marianne Faithfull for Come My Way in 1965 and by Pete Seeger for Dangerous Songs!? in 1966.[126] Michael Nyman's Ariel Songs are taken from his score for the film Prospero's Books.

Among those who wrote incidental music to The Tempest are:

- Arthur Sullivan: his graduation piece, completed in 1861, was a set of incidental music to "The Tempest".[127] Revised and expanded, it was performed at The Crystal Palace in 1862, a year after his return to London, and was an immediate sensation.[128][129]

- Ernest Chausson: in 1888 he wrote incidental music for La tempête, a French translation by Maurice Bouchor. This is believed to be the first orchestral work that made use of the celesta.[130][131]

- Jean Sibelius: his 1926 incidental music was written for a lavish production at the Royal Theatre in Copenhagen. An epilogue was added for a 1927 performance in Helsinki.[132] He represented individual characters through instrumentation choices: particularly admired was his use of harps and percussion to represent Prospero, said to capture the "resonant ambiguity of the character".[133]

- Malcolm Arnold, Lennox Berkeley, Hector Berlioz, Arthur Bliss, Engelbert Humperdinck, Willem Pijper and Henry Purcell.

At least forty-six operas or semi-operas based on The Tempest exist.[134] In addition to the Dryden/Davenant and Garrick versions mentioned in the "Restoration and 18th century" section above, Frederic Reynolds produced an operatic version in 1821, with music by Sir Henry Bishop. Other pre-20th-century operas based on The Tempest include Fromental Halévy's La Tempesta (1850) and Zdeněk Fibich's Bouře (1894).

In the 20th century, Kurt Atterberg's Stormen premiered in 1948 and Frank Martin's Der Sturm in 1955. Michael Tippett's 1971 opera The Knot Garden contains various allusions to The Tempest. In Act 3, a psychoanalyst, Mangus, pretends to be Prospero and uses situations from Shakespeare's play in his therapy sessions.[135] John Eaton, in 1985, produced a fusion of live jazz with pre-recorded electronic music, with a libretto by Andrew Porter. Michael Nyman's 1991 opera Noises, Sounds & Sweet Airs was first performed as an opera-ballet by Karine Saporta. This opera is unique in that the three vocalists, a soprano, contralto, and tenor, are voices rather than individual characters, with the tenor just as likely as the soprano to sing Miranda, or all three sing as one character.[136]

The soprano who sings the part of Ariel in Thomas Adès's 21st-century opera is stretched at the higher end of the register, highlighting the androgyny of the role.[137][138] Mike Silverman of the Associated Press commented, "Adès has made the role of the spirit Ariel a tour de force for coloratura soprano, giving her a vocal line that hovers much of the time well above high C."

Luca Lombardi's Prospero was premiered 2006 at Nuremberg Opera House. Ariel is sung by 4 female voices (S,S,MS,A) and has an instrumental alter ego on stage (flute). There is an instrumental alter ego (cello) also for Prospero.

Choral settings of excerpts from The Tempest include Amy Beach's Come Unto These Yellow Sands (SSAA, from Three Shakespeare Songs), Matthew Harris's Full Fathom Five, I Shall No More to Sea, and Where the Bee Sucks (SATB, from Shakespeare Songs, Books I, V, VI), Ryan Kelly's The Tempest (SATB, a setting of the play's Scene I), Jaakko Mäntyjärvi's Full Fathom Five and A Scurvy Tune (SATB, from Four Shakespeare Songs and More Shakespeare Songs), Frank Martin's Songs of Ariel (SATB), Ralph Vaughan Williams' Full Fathom Five and The Cloud-capp'd Towers (SATB, from Three Shakespeare Songs), and David Willcocks's Full Fathom Five (SSA).

Orchestral works for concert presentation include Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky's fantasy The Tempest (1873), Fibich's symphonic poem Bouře (1880), John Knowles Paine's symphonic poem The Tempest (1876), Benjamin Dale's overture (1902), Arthur Honegger's orchestral prelude (1923), Felix Weingartner's overture "Der Sturm", Heorhiy Maiboroda's overture, and Egon Wellesz's Prosperos Beschwörungen (five works 1934–36).

Ballet sequences have been used in many performances of the play since Restoration times.[139] A one-act ballet of The Tempest by choreographer Alexei Ratmansky was premiered by American Ballet Theatre set to the incidental music of Jean Sibelius on 30 October 2013 in New York City.

Ludwig van Beethoven's 1802 Piano Sonata No. 17 in D minor, Op. 31, No. 2, was given the subtitle "The Tempest" some time after Beethoven's death because, when asked about the meaning of the sonata, Beethoven was alleged to have said "Read The Tempest". But this story comes from his associate Anton Schindler, who is often not trustworthy.[140]

Stage musicals derived from The Tempest have been produced. A production called The Tempest: A Musical was produced at the Cherry Lane Theatre in New York City in December 2006, with a concept credited to Thomas Meehan and a script by Daniel Neiden (who also wrote the songs) and Ryan Knowles.[141] Neiden had previously been connected with another musical, entitled Tempest Toss’d.[142] In September 2013, The Public Theater produced a new large-scale stage musical at the Delacorte Theater in Central Park, directed by Lear deBessonet with a cast of more than 200.[143][144]

Literature and art[edit]

Percy Bysshe Shelley was one of the earliest poets to be influenced by The Tempest. His "With a Guitar, To Jane" identifies Ariel with the poet and his songs with poetry. The poem uses simple diction to convey Ariel's closeness to nature and "imitates the straightforward beauty of Shakespeare's original songs".[145] Following the publication of Darwin's ideas on evolution, writers began to question mankind's place in the world and its relationship with God. One writer who explored these ideas was Robert Browning, whose poem "Caliban upon Setebos" (1864) sets Shakespeare's character pondering theological and philosophical questions.[146] The French philosopher Ernest Renan wrote a closet drama, Caliban: Suite de La Tempête (Caliban: Sequel to The Tempest), in 1878. This features a female Ariel who follows Prospero back to Milan, and a Caliban who leads a coup against Prospero, after the success of which he actively imitates his former master's virtues.[147] W. H. Auden's "long poem" The Sea and the Mirror takes the form of a reflection by each of the supporting characters of The Tempest on their experiences. The poem takes a Freudian viewpoint, seeing Caliban (whose lengthy contribution is a prose poem) as Prospero's libido.[148]

In 1968 Franco-Caribbean writer Aimé Césaire published Une Tempête, a radical adaptation of the play based on its colonial and postcolonial interpretations, in which Caliban is a black rebel and Ariel is mixed-race. The figure of Caliban influenced numerous works of African literature in the 1970s, including pieces by Taban Lo Liyong in Uganda, Lemuel Johnson in Sierra Leone, Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o in Kenya, and David Wallace of Zambia's Do You Love Me, Master?.[149] A similar phenomenon occurred in late 20th-century Canada, where several writers produced works inspired by Miranda, including The Diviners by Margaret Laurence, Prospero's Daughter by Constance Beresford-Howe and The Measure of Miranda by Sarah Murphy.[150] Other writers have feminised Ariel (as in Marina Warner's novel Indigo) or Caliban (as in Suniti Namjoshi's sequence of poems Snapshots of Caliban).[151]

From the mid-18th century, Shakespeare's plays, including The Tempest, began to appear as the subject of paintings.[152] In around 1735, William Hogarth produced his painting A Scene from The Tempest: "a baroque, sentimental fantasy costumed in the style of Van Dyck and Rembrandt".[152] The painting is based upon Shakespeare's text, containing no representation of the stage, nor of the (Davenant-Dryden centred) stage tradition of the time.[153] Henry Fuseli, in a painting commissioned for the Boydell Shakespeare Gallery (1789) modelled his Prospero on Leonardo da Vinci.[154][155] These two 18th-century depictions of the play indicate that Prospero was regarded as its moral centre: viewers of Hogarth's and Fuseli's paintings would have accepted Prospero's wisdom and authority.[156] John Everett Millais's Ferdinand Lured by Ariel (1851) is among the Pre-Raphaelite paintings based on the play. In the late 19th century, artists tended to depict Caliban as a Darwinian "missing-link", with fish-like or ape-like features, as evidenced in Joseph Noel Paton's Caliban, and discussed in Daniel Wilson's book Caliban: The Missing Link (1873).[157][147][158]

Charles Knight produced the Pictorial Edition of the Works of Shakespeare in eight volumes (1838–43). The work attempted to translate the contents of the plays into pictorial form. This extended not just to the action, but also to images and metaphors: Gonzalo's line about "mountaineers dewlapped like bulls" is illustrated with a picture of a Swiss peasant with a goitre.[159] In 1908, Edmund Dulac produced an edition of Shakespeare's Comedy of The Tempest with a scholarly plot summary and commentary by Arthur Quiller-Couch, lavishly bound and illustrated with 40 watercolour illustrations. The illustrations highlight the fairy-tale quality of the play, avoiding its dark side. Of the 40, only 12 are direct depictions of the action of the play: the others are based on action before the play begins, or on images such as "full fathom five thy father lies" or "sounds and sweet airs that give delight and hurt not".[160]

Fantasy writer Neil Gaiman based a story on the play in one issue (the final issue)[161] of his comics series The Sandman. The comic stands as a sequel to the earlier Midsummer Night's Dream issue.[162] This issue follows Shakespeare over a period of several months as he writes the play, which is named as his last solo project, as the final part of his bargain with the Dream King to write two plays celebrating dreams. The story draws many parallels between the characters and events in the play and Shakespeare's life and family relationships at the time. It is hinted that he based Miranda on his daughter Judith Shakespeare and Caliban on her suitor Thomas Quiney.

As part of Random House's Hogarth Shakespeare series of contemporary reimaginings of Shakespeare plays by contemporary writers, Margaret Atwood's 2016 novel Hag-Seed is based on The Tempest.[163]

Screen[edit]

The Tempest first appeared on the screen in 1905. Charles Urban filmed the opening storm sequence of Herbert Beerbohm Tree's version at Her Majesty's Theatre for a 2 1⁄2-minute flicker, whose individual frames were hand-tinted, long before the invention of colour film. In 1908, Percy Stowe directed a Tempest running a little over ten minutes, which is now a part of the British Film Institute's compilation Silent Shakespeare. Much of its action takes place on Prospero's island before the storm which opens Shakespeare's play. At least two other silent versions, one from 1911 by Edwin Thanhouser, are known to have existed, but have been lost.[164] The plot was adapted for the Western Yellow Sky, directed by William A. Wellman, in 1946.[165]

The 1956 science fiction film Forbidden Planet set the story on a planet in space, Altair IV, instead of an island. Professor Morbius and his daughter Altaira (Anne Francis) are the Prospero and Miranda figures (both Prospero and Morbius having harnessed the mighty forces that inhabit their new homes). Ariel is represented by the helpful Robby the Robot, while Sycorax is replaced with the powerful race of the Krell. Caliban is represented by the dangerous and invisible "monster from the id", a projection of Morbius' psyche born from the Krell technology instead of Sycorax's womb.[166]

In the opinion of Douglas Brode, there has only been one screen "performance" of The Tempest since the silent era, he describes all other versions as "variations". That one performance is the Hallmark Hall of Fame version from 1960, directed by George Schaefer, and starring Maurice Evans as Prospero, Richard Burton as Caliban, Lee Remick as Miranda, and Roddy McDowall as Ariel. It cut the play to slightly less than ninety minutes. Critic Virginia Vaughan praised it as "light as a soufflé, but ... substantial enough for the main course."[164]

A 1969 episode of the television series Star Trek, "Requiem for Methuselah", again set the story in space on the apparently deserted planet Holberg 917-G.[167] The Prospero figure is Flint (James Daly), an immortal man who has isolated himself from humanity and controls advanced technology that borders on magic. Flint's young ward Rayna Kapec (Louise Sorel) fills the Miranda role, and Flint's versatile robotic servant M4 parallels Ariel.[168]

In 1979, Derek Jarman produced the homoerotic film The Tempest that used Shakespeare's language, but was most notable for its deviations from Shakespeare. One scene shows a corpulent and naked Sycorax (Claire Davenport) breastfeeding her adult son Caliban (Jack Birkett). The film reaches its climax with Elisabeth Welch belting out Stormy Weather.[169][170] The central performances were Toyah Willcox' Miranda and Heathcote Williams' Prospero, a "dark brooding figure who takes pleasure in exploiting both his servants".[171]

Several other television versions of the play have been broadcast; among the most notable is the 1980 BBC Shakespeare production, virtually complete, starring Michael Hordern as Prospero.

Paul Mazursky's 1982 modern-language adaptation Tempest, with Philip Dimitrius (Prospero) as a disillusioned New York architect who retreats to a lonely Greek island with his daughter Miranda after learning of his wife Antonia's infidelity with Alonzo, dealt frankly with the sexual tensions of the characters' isolated existence. The Caliban character, the goatherd Kalibanos, asks Philip which of them is going to have sex with Miranda.[171] John Cassavetes played Philip, Raul Julia Kalibanos, Gena Rowlands Antonia and Molly Ringwald Miranda. Susan Sarandon plays the Ariel character, Philip's frequently bored girlfriend Aretha. The film has been criticised as "overlong and rambling", but also praised for its good humour, especially in a sequence in which Kalibanos' and his goats dance to Kander and Ebb's New York, New York.[172]

John Gielgud has written that playing Prospero in a film of The Tempest was his life's ambition. Over the years, he approached Alain Resnais, Ingmar Bergman, Akira Kurosawa, and Orson Welles to direct.[173] Eventually, the project was taken on by Peter Greenaway, who directed Prospero's Books (1991) featuring "an 87-year-old John Gielgud and an impressive amount of nudity".[174] Prospero is reimagined as the author of The Tempest, speaking the lines of the other characters, as well as his own.[104] Although the film was acknowledged as innovative in its use of Quantel Paintbox to create visual tableaux, resulting in "unprecedented visual complexity",[175] critical responses to the film were frequently negative: John Simon called it "contemptible and pretentious".[176][177]

The Swedish-made 1989 animated film Resan till Melonia (directed by Per Åhlin) is an adaptation of the Shakespeare play, focusing on ecological values. Resan till Melonia was critically acclaimed for its stunning visuals drawn by Åhlin and its at times quite dark and nightmare-like sequences, even though the film was originally marketed for children.

Director Julie Taymor's 2010 adaptation The Tempest starred Helen Mirren as a female version of Prospero.

Closer to the spirit of Shakespeare's original, in the view of critics such as Brode, is Leon Garfield's abridgement of the play for S4C's 1992 Shakespeare: The Animated Tales series. The 29-minute production, directed by Stanislav Sokolov and featuring Timothy West as the voice of Prospero, used stop-motion puppets to capture the fairy-tale quality of the play.[178]

Another "offbeat variation" (in Brode's words) was produced for NBC in 1998: Jack Bender's The Tempest featured Peter Fonda as Gideon Prosper, a Southern slave-owner forced off his plantation by his brother shortly before the Civil War. A magician who has learned his art from one of his slaves, Prosper uses his magic to protect his teenage daughter and to assist the Union Army.[179]

Notes and references[edit]

All references to The Tempest, unless otherwise specified, are taken from the Folger Shakespeare Library's Folger Digital Editions texts edited by Barbara Mowat, Paul Werstine, Michael Poston, and Rebecca Niles. Under their referencing system, 4.1.165 means act 4, scene 1, line 165.

Notes[edit]

- ^ In 1606, William Burton published Seven dialogues both pithie and profitable with translations into English of seven of the Colloquia; among them "Naufragium A pittifull, yet pleasant Dialogue of a Shipwracke, shewing what comfort Popery affoordeth in time of daunger".[17]

References[edit]

- ^ 5.1.54–57

- ^ Berger, Harry. "Miraculous Harp; A Reading of Shakespeare’s Tempest". Shakespeare Studies. 5 (1969), p. 254.

- ^ Orgel 1987, pp. 43–50.

- ^ Shakespeare, William; Frye, Northrup, editor. (1959). The Tempest. Pelican. pp. 1–10. ISBN 978-0-14-071415-9

- ^ (1.2.350–352)

- ^ (3.2.103–105)

- ^ (4.1.52–54)

- ^ (1.2.18)

- ^ (4.1.39–43)

- ^ Vaughan & Vaughan 1999, pp. 67–73.

- ^ Boğosyan, Natali (2013). Postfeminist Discourse in Shakespeare’s The Tempest and Warner’s Indigo. Cambridge Scholars Publishing, ISBN 978-1-4438-4904-3 pp. 67–69

- ^ Garber, Marjorie (2005). Shakespeare After All. Anchor Press ISBN 978-0-385-72214-8

- ^ a b Orgel 1987, pp. 63–64.

- ^ Vaughan & Vaughan 1999, pp. 1–6.

- ^ Pollard 2002, p. 111.

- ^ Coursen 2000, p. 7.

- ^ Bullough 1975, pp. 334–339.

- ^ Kermode 1958, pp. xxxii–xxxiii.

- ^ a b Vaughan & Vaughan 1999, p. 287.

- ^ Chambers 1930, pp. 490–494.

- ^ Muir 2005, p. 280.

- ^ Malone 1808.

- ^ Howell, Peter. "Tis a mad world at Hogsdon: Leisure, Licence and the Exoticism of Suburban Space in Early Jacobean London". The Literary London Journal. 10 (2 (Autumn 2013)).

- ^ Vaughan & Vaughan 1999, p. 12.

- ^ Vaughan & Vaughan 1999, p. 61.

- ^ Vaughan & Vaughan 1999, pp. 26, 58–59, 66.

- ^ Blayney, Peter W.M. (1991). The First Folio of Shakespeare. Folger Shakespeare Library; First edition ISBN 978-0-9629254-3-6

- ^ (1.2.112)

- ^ Orgel 1987, pp. 56–62.

- ^ Hinman, Charlton (1963). The Printing and Proof Reading of the First Folio of Shakespeare. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-811613-4

- ^ Vaughan & Vaughan 1999, pp. 124–138.

- ^ Orgel 1987, pp. 178.

- ^ Coursen 2000, pp. 1–2.

- ^ The Tempest, 4.1.165–175.

- ^ Gibson 2006, p. 82.

- ^ Vaughan & Vaughan 1999, p. 254.

- ^ Orgel 1987, p. 27.

- ^ Orgel 1987, pp. 1, 10, 80.

- ^ Mohamed Salah Eddine Madiou (2019) ‘Argier’ through Renaissance Drama: Investigating History, Studying Etymology and Reshuffling Geography. The Arab World Geographer: Spring/Summer 2019, Vol. 22, No. 1-2, pp. 120-149.

- ^ a b Hirst 1984, pp. 22–25.

- ^ (1.2.272–274)

- ^ (1.2.277–279)

- ^ (2.1.298–300)

- ^ (5.1.1)

- ^ (1.2.178)

- ^ Hirst 1984, pp. 25–29.

- ^ (5.1.130–132)

- ^ (5.1.183)

- ^ a b Hirst 1984, pp. 22–29.

- ^ (5.1.126–129)

- ^ Kott, Jan (1964). Shakespeare, Our Contemporary. Doubleday ISBN 978-2-228-33440-2 pp. 279–285.

- ^ Orgel 1987, p. 60.

- ^ Hirst 1984, pp. 13–16, 35–38.

- ^ Vaughan & Vaughan 1999, pp. 14–17.

- ^ Hirst 1984, pp. 34–35.

- ^ The Tempest, 5.1.1–7.

- ^ Vaughan & Vaughan 1999, p. 262n.

- ^ Vaughan & Vaughan 1999, p. 4.

- ^ Vaughan & Vaughan 1999, pp. 98–108.

- ^ Orgel 1987, pp. 83–85.

- ^ Bose, Siddhartha (2015). Back and Forth: The Grotesque in the Play of Romantic Irony. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4438-7581-3.

- ^ Duckett, Katharine (23 March 2015). "Unreliable Histories: Language as Power in The Tempest". Tor.com. Retrieved 10 May 2019.

- ^ Carey-Webb 1993, pp. 30–35.

- ^ a b Cartelli 1995, pp. 82–102.

- ^ Nixon 1987, pp. 557–578.

- ^ Ridge, Kelsey (November 2016). "'This Island's Mine': Ownership of the Island in The Tempest". Studies in Ethnicity and Nationalism. 16 (2): 231–245. doi:10.1111/sena.12189.

- ^ Dolan, Jill (1991). The Feminist Spectator as Critic. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. p. 996

- ^ Auerbach, Nina (1982). Women and the Demon. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. p. 210

- ^ Disch, Lisa; Hawkesworth, Mary editors (2018). The Oxford Handbook of Feminist Theory. pp. 1–16. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-062361-6

- ^ Boğosyan, Natali (2013). Postfeminist Discourse in Shakespeare’s The Tempest and Warner’s Indigo. Cambridge Scholars Publishing, ISBN 978-1-4438-4904-3 pp. 67–69

- ^ Orgel, Stephen (1996). Impersonations: The Performance of Gender in Shakespeare’s England. New York: Cambridge University Press. pp. 13–25

- ^ Coursen 2000, pp. 87–88.

- ^ (1.2.56–57)

- ^ (1.2.118–120)

- ^ Orgel 1984.

- ^ "Brave New World", Wikipedia, 8 February 2020, retrieved 8 February 2020

- ^ "'Brave new world' of genome sequencing - Big Ideas - ABC Radio National". web.archive.org. 8 February 2020. Retrieved 8 February 2020.

- ^ "Stage History | The Tempest". Royal Shakespeare Company. Retrieved 1 November 2018.

- ^ Chambers 1930, p. 343.

- ^ Dymkowski 2000, p. 5n.

- ^ Gurr 1989, pp. 91–102.

- ^ Vaughan & Vaughan 1999, pp. 6–7.

- ^ a b Vaughan & Vaughan 1999, p. 76.

- ^ Marsden 2002, p. 21.

- ^ Vaughan & Vaughan 1999, p. 77.

- ^ Marsden 2002, p. 26.

- ^ Dobson 1992, pp. 59–60.

- ^ Vaughan & Vaughan 1999, pp. 76–77.

- ^ Auberlen 1991.

- ^ Vaughan & Vaughan 1999, p. 80.

- ^ a b c Vaughan & Vaughan 1999, pp. 82–83.

- ^ The Tempest, 1.2.444–445.

- ^ Moody 2002, p. 44.

- ^ Moody 2002, p. 47.

- ^ Vaughan & Vaughan 1999, p. 89.

- ^ Schoch 2002, pp. 58–59.

- ^ Schoch 2002, p. 64.

- ^ Schoch 2002, pp. 67–68.

- ^ Halliday 1964, pp. 486–487.

- ^ a b Vaughan & Vaughan 1999, pp. 93–95.

- ^ a b Vaughan & Vaughan 1999, p. 113.

- ^ The Tempest, 4.1.163–180.

- ^ Vaughan & Vaughan 1999, pp. 96–98.

- ^ a b Brode 2001, p. 229.

- ^ Dymkowski 2000, p. 21.

- ^ Spencer 2003.

- ^ Croyden 1969, p. 127.

- ^ Vaughan & Vaughan 1999, pp. 113–114.

- ^ Hirst 1984, p. 50.

- ^ a b Vaughan & Vaughan 1999, p. 114.

- ^ Billington 1989.

- ^ Saccio 1980.

- ^ Vaughan & Vaughan 1999, pp. 114–115.

- ^ Coveney 2011.

- ^ Vaughan & Vaughan 1999, p. 116.

- ^ Dawson 2002, pp. 179–181.

- ^ Vaughan & Vaughan 1999, pp. 116–117.

- ^ Vaughan & Vaughan 1999, pp. 121–123.

- ^ Gay 2002, pp. 171–172.

- ^ Thomson 2002, p. 138.

- ^ Greenhalgh 2007, p. 186.

- ^ a b Hitchings 2016.

- ^ Sanders 2007, p. 42.

- ^ Vaughan & Vaughan 1999, pp. 18–20.

- ^ Sanders 2007, p. 31.

- ^ Sanders 2007, p. 189.

- ^ Jacobs 1986, p. 24.

- ^ Lawrence 1897.

- ^ Sullivan 1881.

- ^ Blades & Holland 2003.

- ^ Gallois 2003.

- ^ Ylirotu 2005.

- ^ Sanders 2007, p. 36.

- ^ Wilson 1992.

- ^ Vaughan & Vaughan 1999, p. 112.

- ^ Tuttle 1996.

- ^ Sanders 2007, p. 99.

- ^ Halliday 1964, pp. 410, 486.

- ^ Sanders 2007, p. 60.

- ^ Tovey 1931, p. 285.

- ^ McElroy 2006.

- ^ Avery 2006.

- ^ La Rocco 2013.

- ^ Simon 2013.

- ^ Vaughan & Vaughan 1999, pp. 87–88.

- ^ Vaughan & Vaughan 1999, p. 91.

- ^ a b Vaughan & Vaughan 1999, p. 92.

- ^ Vaughan & Vaughan 1999, pp. 110–111.

- ^ Vaughan & Vaughan 1999, p. 107.

- ^ Vaughan & Vaughan 1999, p. 109.

- ^ Vaughan & Vaughan 1999, pp. 109–110.

- ^ a b Orgel 2007, p. 72.

- ^ Orgel 2007, pp. 72–73.

- ^ Orgel 2007, p. 76.

- ^ Vaughan & Vaughan 1999, pp. 83–85.

- ^ Vaughan & Vaughan 1999, pp. 83–84.

- ^ Wilson, Daniel (1873). Caliban: The Missing Link. Macmillan & Co.

- ^ Tyrwhitt, John (1869). Pictures of the Year. Contemporary Review. 11.. p. 364.

- ^ Orgel 2007, p. 81.

- ^ Orgel 2007, pp. 85–88.

- ^ The Sandman #75 (DC Vertigo, March 1996).

- ^ The Sandman #19 (DC, Sept. 1990).

- ^ Cowdrey 2016.

- ^ a b Brode 2001, pp. 222–223.

- ^ Howard 2000, p. 296.

- ^ Vaughan & Vaughan 1999, pp. 111–112.

- ^ Pilkington 2015, p. 44.

- ^ Morse 2000, pp. 168, 170–171.

- ^ Vaughan & Vaughan 1999, pp. 118–119.

- ^ Brode 2001, pp. 224–226.

- ^ a b Vaughan & Vaughan 1999, p. 118.

- ^ Brode 2001, pp. 227–228.

- ^ Jordison 2014.

- ^ Rozakis 1999, p. 275.

- ^ Howard 2003, p. 612.

- ^ Forsyth 2000, p. 291.

- ^ Brode 2001, pp. 229–231.

- ^ Brode 2001, p. 232.

- ^ Brode 2001, pp. 231–232.

Bibliography[edit]

- Auberlen, Eckhard (1991). "The Tempest and the Concerns of the Restoration Court: A Study of The Enchanted Island and the Operatic Tempest". Restoration: Studies in English Literary Culture, 1660–1700. 15: 71–88. ISSN 1941-952X.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Avery, Susan (1 May 2006). "Two Tempests, Both Alike: Shakespearean indignity". New York Magazine. Retrieved 22 February 2015.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Billington, Michael (1 January 1989). "In Britain, a Proliferation of Prosperos". The New York Times. Retrieved 20 December 2008.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Blades, James; Holland, James (2003). "Celesta". In Sadie, Stanley; Tyrrell, John (eds.). The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians. 5. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-517067-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Brode, Douglas (2001). Shakespeare in the Movies: From the Silent Era to Today. New York: Berkley Boulevard Books. ISBN 0-425-18176-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bullough, Geoffrey (1975). Romances: Cymbeline, The Winter's Tale, The Tempest. Narrative and Dramatic Sources of Shakespeare. Routledge and Kegan Paul. ISBN 978-0-7100-7895-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Carey-Webb, Allen (1993). "Shakespeare for the 1990s: A Multicultural Tempest". The English Journal. National Council of Teachers of English. 82 (4): 30–35. doi:10.2307/820844. ISSN 0013-8274. JSTOR 820844. OCLC 1325886.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cartelli, Thomas (1995). "After The Tempest: Shakespeare, Postcoloniality, and Michelle Cliff's New, New World Miranda". Contemporary Literature. University of Wisconsin Press. 36 (1): 82–102. doi:10.2307/1208955. ISSN 0010-7484. JSTOR 1208955. OCLC 38584750.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Chambers, Edmund Kerchever (1930). William Shakespeare: A Study of Facts and Problems. 2. Oxford: Clarendon Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Coursen, Herbert (2000). The Tempest: A Guide to the Play. Westport: Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-31191-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Coveney, Michael (11 August 2011). "Obituary: John Wood: Ferociously intelligent actor who reigned supreme in Stoppard and Shakespeare". The Guardian. p. 34.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cowdrey, Katherine (23 February 2016). "Margaret Atwood reveals title and jacket for Hag-Seed". The Bookseller.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Croyden, Margaret (1969). "Peter Brook's Tempest". The Drama Review. 13 (3): 125–128. doi:10.2307/1144467. JSTOR 1144467.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dawson, Anthony (2002). "International Shakespeare". In Wells, Stanley; Stanton, Sarah (eds.). The Cambridge Companion to Shakespeare on Stage. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 174–193. ISBN 0-521-79711-X.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dobson, Michael (1992). The Making of the National Poet: Shakespeare, Adaptation and Authorship, 1660–1769. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-818323-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dolan, Frances E. (1992). "The Subordinate('s) Plot: Petty Treason and the Forms of Domestic Rebellion". Shakespeare Quarterly. Johns Hopkins University Press. 43 (3): 317–340. doi:10.2307/2870531. ISSN 0037-3222. JSTOR 2870531. OCLC 39852252.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dymkowski, Christine (2000). The Tempest. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-78375-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Forsyth, Neil (2000). "Shakespeare the Illusionist: Filming the Supernatural". In Jackson, Russell (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to Shakespeare on Film. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 274–294. ISBN 0-521-63975-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gallois, Jean (2003). "Ernest Chausson". In Sadie, Stanley; Tyrrell, John (eds.). The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians. 5. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-517067-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gay, Penny (2002). "Women and Shakespearean Performance". In Wells, Stanley; Stanton, Sarah (eds.). The Cambridge Companion to Shakespeare on Stage. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 155–173. ISBN 0-521-79711-X.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gibson, Rex (2006). The Tempest. Cambridge Student Guides. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-53857-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gielgud, John (2005). Mangan, Richard (ed.). Sir John Gielgud: A Life in Letters. Arcade Publishing. ISBN 978-1-55970-755-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Greenhalgh, Susanne (2007). "Shakespeare overheard: performances, adaptations, and citations on radio". In Shaughnessy, Robert (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to Shakespeare and Popular Culture. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 175–198. ISBN 978-0-521-60580-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gurr, Andrew (1989). The Tempest's Tempest at Blackfriars. Shakespeare Survey. 41. Cambridge University Press. pp. 91–102. doi:10.1017/CCOL0521360714.009. ISBN 0-521-36071-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Halliday, F.E. (1964). A Shakespeare Companion 1564–1964. Baltimore: Penguin. ISBN 0-7156-0309-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hirst, David L. (1984). The Tempest: Text and Performance. Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-333-34465-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hitchings, Henry (18 November 2016). "The Tempest: Theatre's traditional virtues endure in tech-heavy show". Evening Standard.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Howard, Tony (2000). "Shakespeare's Cinematic Offshoots". In Jackson, Russell (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to Shakespeare on Film. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-63975-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Howard, Tony (2003). "Shakespeare on Film and Video". In Wells, Stanley; Orlin, Lena Cowen (eds.). Shakespeare: An Oxford Guide. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 607–619. ISBN 0-19-924522-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jackson, Russell, ed. (2000). The Cambridge Companion to Shakespeare on Film. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-63975-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jacobs, Arthur (1986). Arthur Sullivan – A Victorian Musician. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-282033-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jordison, Sam (24 April 2014). "The Tempest Casts Strange Spells at the Cinema". The Guardian.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kennedy, Michael (1992). The Works of Ralph Vaughan Williams. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-816330-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kermode, Frank, ed. (1958). The Tempest. The Arden Shakespeare, second series. Methuen. OL 6244436M.

- La Rocco, Claudia (10 September 2013). "On a Diverse Island, a Play About a Magical One". The New York Times. p. C3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lawrence, Arthur H. (1897). "An illustrated interview with Sir Arthur Sullivan". The Strand Magazine. Vol. xiv no. 84. Archived from the original on 13 December 2014.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Malone, Edmond (1808). An Account of the Incidents, from which the Title and Part of the Story of Shakespeare's Tempest were derived, and its true date ascertained. London: C. and R. Baldwin, New Bridge-Street.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Marsden, Jean I. (2002). "Improving Shakespeare: from the Restoration to Garrick". In Wells, Stanley; Stanton, Sarah (eds.). The Cambridge Companion to Shakespeare on Stage. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 21–36. ISBN 0-521-79711-X.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- McElroy, Steven (24 November 2006). "A New Theater Company Starts Big". Arts, Briefly. The New York Times. p. E2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Moody, Jane (2002). "Romantic Shakespeare". In Wells, Stanley; Stanton, Sarah (eds.). The Cambridge Companion to Shakespeare on Stage. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 37–57. ISBN 0-521-79711-X.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)