Tribe of Benjamin

| |

| Geographical range | West Asia |

|---|---|

| Major sites | Jerusalem |

| Preceded by | New Kingdom of Egypt |

| Followed by | Kingdom of Israel (united monarchy) |

| Tribes of Israel |

|---|

|

| The Tribes |

| Related topics |

According to the Torah, the Tribe of Benjamin (Hebrew: שֵׁבֶט בִּנְיָמִֽן, Shevet Binyamin) was one of the Twelve Tribes of Israel. The tribe was descended from Benjamin, the youngest son of the patriarch Jacob and his wife Rachel. In the Samaritan Pentateuch the name appears as Binyamīm (Hebrew: בנימים).

The Tribe of Benjamin, located to the north of Judah but to the south of the northern Kingdom of Israel, is significant in biblical narratives as a source of various Israelite leaders including the first Israelite king, Saul, as well as earlier tribal leaders in the period of the Judges. In the period of the judges, they feature in an episode in which a civil war results in their near-extinction as a tribe. After the brief period of the united kingdom of Israel, Benjamin became part of the southern kingdom following the split into two kingdoms. After the destruction of the northern kingdom, Benjamin was absorbed into the southern kingdom. When the southern kingdom was destroyed in the early sixth century BCE, Benjamin as an organized tribe faded from history.

Name[edit]

An account in Genesis explains the name of Benjamin as a result of the birth of the tribe's founder, Benjamin. According to Genesis, Benjamin was the result of a painful birth in which his mother died, naming him Ben-Oni, "son of my pain," immediately before her death. Instead, Jacob, his father, preferred to call him Benjamin, which can be read in Hebrew as meaning, "son of my right [hand]" (Genesis 35:16-18). In geographical terms, the term Benjamin can be read as "son of the south" from the perspective of the northern Kingdom of Israel, as the Benjamite territory was at the southern edge of the northern kingdom.[1]

Biblical narrative[edit]

From after the conquest of the promised land by Joshua until the formation of the first Kingdom of Israel, the Tribe of Benjamin was a part of a loose confederation of Israelite tribes. No central government existed, and in times of crisis the people were led by ad hoc leaders known as Judges (see the Book of Judges).

Battle of Gibeah[edit]

The Book of Judges recounts that the rape of the concubine of a member of the tribe of Levi, by a gang from the tribe of Benjamin resulted in a battle at Gibeah, in which the other tribes of Israel sought vengeance, and after which members of Benjamin were killed including women and children. Six hundred of the men from the tribe of Benjamin survived by hiding in a cave for four months.

The other Israelite tribes were grieved at the near loss of the tribe of Benjamin. They decided to allow these 600 men to carry on the tribe of Benjamin but no one was willing to give their daughter in marriage to them because they had vowed not to. To get around this, they provided wives for the men by killing the men from the tribe of Machir who had not shown concern for the almost lost tribe of Benjamin as they did not come to grieve with the rest of Israel. 400 virgin women from the tribe of Machir were found and given in marriage to the Benjaminite men. There were still 200 men remaining who were without a wife so it was agreed that they could go to an Israelite festival and hide in the vineyards, and wait for the young unmarried women to come out and dance. They then grabbed a wife each and took her back to their land and rebuilt their houses (Judges 19-21).

Almost the entire tribe of Benjamin, women and children included, was wiped out by the other Israelite tribes after the Battle of Gibeah (related in the Hebrew Bible in Judges 20). The text refers several times to the Benjaminite warriors as "men of valour"[2] despite their defeat. A remnant of the tribe was spared: "those few who remained"[3] married virgins from Jabesh Gilead after the Israelites killed all the other inhabitants of the town (Judges 21).

United Kingdom of Israel[edit]

Responding to a growing threat from Philistine incursions, the Israelite tribes formed a strong, centralised monarchy during the eleventh century BC. The first king of this new entity was Saul, from the tribe of Benjamin (1 Samuel 9:1-2), which at the time was the smallest of the tribes. He reigned from Gibeah for 38 years (1 Samuel 8:31).

After Saul died, all the tribes other than Judah remained loyal to the House of Saul and to Ish-bosheth, Saul's son and successor to the throne of Israel, but war ensued between the House of Saul and the House of David.[4] The account in 2 Samuel 3 stresses that Israel's military commander Abner, negotiating with the tribes to secure a peace treaty with David, then king of Judah, held talks specifically with the house of Benjamin to secure their support.[4] The Cambridge Bible for Schools and Colleges suggests that the tribe of Benjamin "was the most likely to offer opposition [to Abner] through fear of losing dignity and advantage by the transference of the royal house to the tribe of Judah.[5]

Later history[edit]

After the death of Ish-bosheth, the tribe of Benjamin joined the northern Israelite tribes in making David king of the united Kingdom of Israel and Judah. On the accession of Rehoboam, David's grandson, in c. 930 BCE the northern tribes split from the House of David to constitute the northern Kingdom of Israel. The tribe of Benjamin remained a part of the Kingdom of Judah until Judah was conquered by Babylon in c. 586 BCE and the population deported.

After the dissolution of the united Kingdom of Israel in c. 930 BCE, the Tribe of Benjamin joined the Tribe of Judah as a junior partner in the Kingdom of Judah, or Southern Kingdom. The Davidic dynasty, which had roots in Judah, continued to reign in Judah. As part of the kingdom of Judah, Benjamin survived the destruction of Israel by the Assyrians, but instead was subjected to the Babylonian captivity; when the captivity ended, the distinction between Benjamin and Judah was lost in favour of a common identity as Israel, though in the biblical book of Esther, Mordecai is referred to as being of the tribe of Benjamin,[6] and as late as the time of Jesus of Nazareth some (notably Paul the Apostle) still identified their Benjamite ancestry:

- If anyone else thinks he may have confidence in the flesh, I more so: circumcised on the eighth day, of the stock of Israel, of the tribe of Benjamin, a Hebrew of the Hebrews; concerning the law, a Pharisee; concerning zeal, persecuting the church; concerning the righteousness which is in the law, blameless.” [7]

Character[edit]

Several passages in the Bible describe tribe of Benjamin as being pugnacious,[8] for example in the Song of Deborah, and in descriptions where they are described as being taught to fight left handed, so as to be able to wrong foot their enemies (Judges 3:15-21, 20:16, 1 Chronicles 12:2) and where they are portrayed as being brave and skilled archers (1 Chronicles 8:40, 2 Chronicles 14:8).

In the Blessing of Jacob, Benjamin is referred to as "a ravenous wolf";[9] traditional interpretations often considered this to refer to the might of a specific member of the tribe, either the champion Ehud, king Saul, or Mordecai of the Esther narrative, or in Christian circles, the apostle Paul.[8] The Temple in Jerusalem was traditionally said to be partly in the territory of the tribe of Benjamin (but mostly in that of Judah), and some traditional interpretations of the Blessing consider the ravenous wolf to refer to the Temple's altar which devoured biblical sacrifices.[8]

Territory[edit]

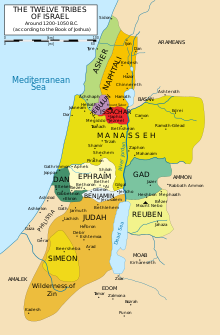

According to the Hebrew Torah, following the completion of the conquest of Canaan by the Israelite tribes, Joshua allocated the land among the twelve tribes. Kenneth Kitchen dates this conquest to just after 1200 BCE.[10] However, according to the consensus of modern scholars, the conquest as described in the book of Joshua did not occur.[11][12][13]

The Bible recounts that Joshua assigned to Benjamin the territory between that of Ephraim to the north and Judah to the south, with the Jordan River as the eastern border, and included many historically important cities, such as Bethel, Gibeah, and encroached on the northern hills of Jerusalem. (Joshua 18:11-28)

According to rabbinical sources, only those towns and villages on the northern-most and southern-most territorial boundary lines, or purlieu, are named in the land allocation, although, in actuality, all unnamed towns and villages in between these boundaries would still belong to the tribe of Benjamin.[14] The Babylonian Talmud names three of these cities, all of which were formerly enclosed by a wall, and belonged to the tribe of Benjamin: Lydda (Lod), Ono (Kafr 'Ana),[15][16] and Gei Ha-ḥarashim.[17] Marking what is now one of the southern-most butts and bounds of Benjamin's territory is "the spring of the waters of Nephtoah" (Josh. 18:15), a place identified as Kefar Lifta (كفر لفتا), and situated on the left-hand side of the road as one enters Jerusalem. It is now an abandoned Arab village. The word Lifta is merely a corruption of the Hebrew name Nephtoah, and where a natural spring by that name still abounds.[18]

Although Jerusalem was in the territory allocated to the tribe of Benjamin (Joshua 18:28), it remained under the independent control of the Jebusites. Judges 1:21 points to the city being within the territory of Benjamin, while Joshua 15:63 implies that the city was within the territory of Judah. In any event, Jerusalem remained an independent Jebusite city until it was finally conquered by David[19] in c. 11th century BC and made into the capital of the united Kingdom of Israel.[20] After the breakup of the United Monarchy, Jerusalem continued as the capital of the southern Kingdom of Judah.

The ownership of Bethel is also ambiguous. Though Joshua allocated Bethel to Benjamin, by the time of the prophetess Deborah, Bethel is described as being in the land of the Tribe of Ephraim (Judges 4:5). Then, some twenty years after the breakup of the United Monarchy, Abijah, the second king of Kingdom of Judah, defeated Jeroboam of Israel and took back the towns of Bethel, Jeshanah and Ephron, with their surrounding villages.[21] Ephron is believed to be the Ophrah that was also allocated to the Tribe of Benjamin by Joshua.[22]

The Blessing of Moses, portrayed in the Bible as a prophecy by Moses about the future situation of the twelve tribes, describes Benjamin as "dwelling between YHWH's shoulders," in reference to its location between the leading tribe of the Kingdom of Israel (Ephraim), and the leading tribe (Judah) of Kingdom of Judah.[23]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ Benjamin D. Giffone (20 October 2016). 'Sit At My Right Hand': The Chronicler's Portrait of the Tribe of Benjamin in the Social Context of Yehud. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 100. ISBN 978-0-567-66732-8.

- ^ Judges 20:44-46; the Cambridge Bible for Schools and Colleges suggests that the description should only have occurred once, in verse 46, and also appeared in verse 44 as the result of "a copyist's error". G. A. Cooke (1913). A. F. Kirkpatrick (ed.). The Book of Judges. The Cambridge Bible For Schools And Colleges. Edinburgh: Cambridge University Press. p. 191.

- ^ Judges 21:7 in the New Living Translation

- ^ a b 2 Samuel 3:19

- ^ Cambridge Bible for Schools and Colleges on 2 Samuel 3, accessed 6 July 2017. A. F. Kirkpatrick (1881). J. J. S. Perowne (ed.). The Second Book of Samuel. The Cambridge Bible for Schools and Colleges. Cambridge University Press. p. 71.

- ^ Esther 2:5

- ^ Philippians 3:4b-6

- ^ a b c Gottheil, Richard, et al. (1906) "Benjamin," in the Jewish Encyclopedia.

- ^ Genesis 49:27

- ^ Kitchen, Kenneth A. (2003), "On the Reliability of the Old Testament" (Grand Rapids, Michigan. William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company)(ISBN 0-8028-4960-1)

- ^ “Besides the rejection of the Albrightian 'conquest' model, the general consensus among OT scholars is that the Book of Joshua has no value in the historical reconstruction. They see the book as an ideological retrojection from a later period — either as early as the reign of Josiah or as late as the Hasmonean period.” K. Lawson Younger Jr. (1 October 2004). "Early Israel in Recent Biblical Scholarship". In David W. Baker; Bill T. Arnold (eds.). The Face of Old Testament Studies: A Survey of Contemporary Approaches. Baker Academic. p. 200. ISBN 978-0-8010-2871-7.

- ^ ”It behooves us to ask, in spite of the fact that the overwhelming consensus of modern scholarship is that Joshua is a pious fiction composed by the deuteronomistic school, how does and how has the Jewish community dealt with these foundational narratives, saturated as they are with acts of violence against others?" Carl S. Ehrlich (1999). "Joshua, Judaism and Genocide". Jewish Studies at the Turn of the Twentieth Century, Volume 1: Biblical, Rabbinical, and Medieval Studies. BRILL. p. 117. ISBN 90-04-11554-4.

- ^ ”Recent decades, for example, have seen a remarkable reevaluation of evidence concerning the conquest of the land of Canaan by Joshua. As more sites have been excavated, there has been a growing consensus that the main story of Joshua, that of a speedy and complete conquest (e.g. Josh. 11.23: 'Thus Joshua conquered the whole country, just as the LORD had promised Moses') is contradicted by the archaeological record, though there are indications of some destruction and conquest at the appropriate time." Adele Berlin; Marc Zvi Brettler (17 October 2014). The Jewish Study Bible: Second Edition. Oxford University Press. p. 951. ISBN 978-0-19-939387-9.

- ^ Rashi on Joshua 15:21; Babylonian Talmud, Baba Bathra 51a; Gittin 7a.

- ^ Ishtori Haparchi, Kaphtor u'ferach (ed. Avraham Yosef Havatzelet), vol. II (third edition), chapter 11, s.v. מלוד לאונו, Jerusalem 2007, p. 75 (note 265)(Hebrew). Kafr 'Ana actually represents a Byzantine-period expansion of a nearby and much older site –– Kafr Juna, believed to be the ancient Ono. See p. 175 in: Taxel, Itamar (May 2013). "Rural Settlement Processes in Central Palestine, ca. 640–800 c.e.: The Ramla-Yavneh Region as a Case Study". Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research (369): 157–199. JSTOR 10.5615/bullamerschoorie.369.0157.

- ^ Page 19 in: Maisler, Benjamin (1932). "A Memo of the National Committee to the Government of the Land of Israel on the Method of Spelling Transliterated Geographical and Personal Names, plus Two Lists of Geographical Names". Lĕšonénu: A Journal for the Study of the Hebrew Language and Cognate Subjects (in Hebrew). 4 (3): 19. JSTOR 24384308.

- ^ Tractate Megillah 4a

- ^ Khalidi, Walid (1991) All That Remains: The Palestinian Villages Occupied and Depopulated by Israel in 1948. Institute for Palestine Studies: Washington, D.C. 1992, pp. 300-303.

- ^ 1 Chronicles 11:4-8

- ^ Greenfeld, Howard (2005-03-29). A Promise Fulfilled: Theodor Herzl, Chaim Weizmann, David Ben-Gurion, and the Creation of the State of Israel. Greenwillow. p. 32. ISBN 0-06-051504-X.

- ^ 2 Chronicles 13:17-19

- ^ Joshua 18:20-28, esp 23

- ^ Deuteronomy 33:12

External links[edit]

- Map of the Tribe of Benjamin, Adrichem, 1590. Eran Laor Cartographic Collection, The National Library of Israel.

- Map of the Tribe of Benjamin, Fuller, 1650. Eran Laor Cartographic Collection, The National Library of Israel.