Witch of Endor

| The Witch of Endor | |

|---|---|

| Book of Samuel character | |

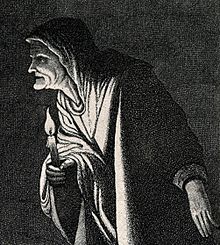

"The Endorian Sorceress Causes the Shade of Samuel" (Martynov, Dmitry Nikiforovich, 1857) | |

| In-universe information | |

| Gender | Female |

| Occupation | necromancer, Mediumship |

| Nationality | Endor (Galilee), Canaanite city |

In the Hebrew Bible, the Witch of Endor is a woman Saul consulted to summon the spirit of prophet Samuel in the 28th chapter of the First Book of Samuel in order to receive advice against the Philistines in battle after his prior attempts to consult God through sacred lots and prophets had failed.[1][2] The witch is absent from the version of that event recounted in the deuterocanonical Book of Sirach (46:19–20).

Later Christian theology found trouble with this passage as it appeared to imply that the witch had summoned the spirit of Samuel and, therefore, necromancy and magic were possible.

Etymology[edit]

She is called in Biblical Hebrew אֵשֶׁת בַּעֲלַת־אֹוב בְּעֵין דֹּור (’êšeṯ ba‘ălaṯ-’ōḇ bə-‘ên dōr), "a woman, possessor of an ’ōḇ at Endor". The word אֹ֖וב ’ōḇ has been suggested by Harry Hoffner to refer to a ritual pit for summoning the dead from the netherworld, based on parallels in other Near Eastern and Mediterranean cultures. The word has cognates in other regional languages (cf. Sumerian ab, Akkadian âbu, Hittite a-a-bi, Ugaritic ib) and the witch of Endor's ritual has parallels in Babylonian and Hittite magical texts as well as the Odyssey.[3][4] Other suggestions for a definition of ’ōḇ include a familiar spirit, a talisman,[5] wineskin, or a reference to ventriloquism[6] based on the Septuagint translation.

The witch also claims to see "elohim arising" (plural verb) from the ground, using the word typically translated as "god(s)" to refer to the spirits of the dead. This is also paralleled by the use of the Akkadian cognate word ilu "god" in a similar fashion.[7]

In the Greek Septuagint, she is called ἐγγαστρίμυθος ἐν Αενδωρ engastrímythos en Aendōr, while the Latin Vulgate as pythonem in Aendor, both terms referencing then-contemporary pagan oracles.

Story[edit]

When Samuel dies, he is buried in Ramah. Saul, the current King of Israel, seeks wisdom from God in choosing a course of action against the assembled forces of the Philistines. He receives no answer from dreams, prophets, or the Urim and Thummim. Having driven out all necromancers and magicians from Israel, Saul searches for a witch anonymously and in disguise. His search leads him to a woman of Endor, who claims that she can see the ghost of Samuel rising from the abode of the dead.[8]

The voice of the prophet's ghost at first frightens the witch of Endor, and after complaining of being disturbed, berates Saul for disobeying God, and predicts Saul's downfall. The spirit reiterates a pre-mortem prophecy by Samuel, adding that Saul will perish with his whole army in battle the next day. Saul is terrified. The next day, his army is defeated as prophesied, Saul is fatally wounded by the Philistines, and in two different tellings of the event, commits suicide by using his own sword, or asks a youth to strike him down.

Although Saul is depicted as an enemy to witches and diviners, the Witch of Endor comforts Saul when she sees his distress and insists on feeding him before he leaves.

Since this passage states the witch made a loud cry in fear when she saw Samuel's spirit, some interpretreters reject the suggestion that the witch was responsible for summoning Samuel's spirit, instead, this was the work of God.[9][10] Joyce Baldwin writes that "The Incident does not tell us anything about the veracity of claims to consult the dead on the part of mediums, because the Indications are that this was an extraordinary event for her (the woman), and a frightening one because she was not in control."[11]

In the German language-translation by Martin Luther (Luther Bible), which is based on Hebrew and Greek texts, a different interpretation is given. It is implied that the woman screams because she realizes that she is talking to the king who recently outlawed all forms of wizardry, but not because she is startled by a spirit ("Als nun das Weib merkte, daß es um Samuel ging, schrie sie laut..." , translation: "When the woman realized that it was about Samuel, she cried with a loud voice...") [12].

Interpretations[edit]

Judaism[edit]

The Yalkut Shimoni (11th century) identifies the anonymous witch as the mother of Abner.[13] Based upon the witch's claim to have seen something, and Saul having heard a disembodied voice, the Yalkut suggests that necromancers are able to see the spirits of the dead but are unable to hear their speech, while the person for whom the deceased was summoned hears the voice but fails to see anything.[5]

Antoine Augustin Calmet briefly mentioned the witch of Endor in his Traité sur les apparitions des esprits et sur les vampires ou les revenans de Hongrie, de Moravie, &c. (1759):[14]

The Israelites went sometimes to consult Beelzebub, god of Ekron, to know if they should recover from their sickness. The history of the evocation of Samuel by the witch of Endor is well known. I am aware that some difficulties are raised concerning this history. I shall deduce nothing from it here, except that this woman passed for a witch, that Saul esteemed her such, and that this prince had exterminated the magicians in his own states, or, at least, that he did not permit them to exercise their art.

— Calmet, Chapter 7 on Magic

The Jews of our days believe that after the body of a man is interred, his spirit goes and comes, and departs from the spot where it is destined to visit his body, and to know what passes around him; that it is wandering during a whole year after the death of the body, and that it was during that year of delay that the Pythoness of Endor evoked the soul of Samuel, after which time the evocation would have had no power over his spirit.

— Calmet, Chapter 40

Christianity[edit]

The Church Fathers and some modern Christian writers have debated the theological issues raised by this text. The story of King Saul and the Witch of Endor would appear at first sight to affirm that it is possible (though forbidden) for humans to summon the spirits of the dead by magic.

In the Septuagint (2nd century BC) the woman is described as a "ventriloquist",[15] possibly reflecting the consistent view of the Alexandrian translators concerning "demons ... which exist not".[16] However, Josephus (1st century) appears to find the story completely credible (Antiquities of the Jews 6,14).

King James wrote in his philosophical treatise Daemonologie (1597) arguing against the ventriloquist theory, stating that the Devil is permitted at times to put himself in the likeness of the Saints, citing 2 Corinthians 11:14 that Satan can transform himself into an Angel of light.[17] James describes the witch of Endor as "Saul's Pythonese", likening her to Pythia from the Greek mythology of Python and the Oracle. It was the belief of James that the witch of Endor was an avid practitioner of necromancy:[18]

... that how soon that once the unclean spirit was fully risen, she called in upon Saul. For it is said in the text, that Saul knew him to be Samuel, which could not have been by the hearing tell only of an old man with a mantle ... But to prove this my first proposition, that there can be such a thing as witchcraft, & witches, there are many more places in the Scriptures than this (as I said before). As first in the law of God, it is plainly prohibited: (Exod. 22.) But certain it is, that the Law of God speaks nothing in vain, neither does it lay curses, or enjoin punishments upon shadows, condemning that to be ill, which is not in essence or being as we call it.

— Epistemon; Daemonologie, Chapter 1

Other medieval glosses to the Bible also suggested that what the witch summoned was not the ghost of Samuel, but a demon taking his shape or an illusion crafted by the witch.[19] Martin Luther, who believed that the dead were unconscious, read that it was "the Devil's ghost", whereas John Calvin read that "it was not the real Samuel, but a spectre."[20]

Spiritualism[edit]

Spiritualists have taken the story as evidence of spirit mediumship in ancient times. The story has been cited in debates between Spiritualist apologists and Christian critics. "The woman of Endor was a medium, respectable, honest, law-abiding, and far more Christ-like than" Christian critics of Spiritualism, asserted one Chicago Spiritualist paper in 1875.[21]

Calmet states,[22]

The pagans thought much in the same manner upon it. Lucan introduces Pompey, who consults a witch, and commands her to evoke the soul of a dead man to reveal to him what success he would meet with in his war against Cæsar; the poet makes this woman say, "Shade, obey my spells, for I evoke not a soul from gloomy Tartarus, but one which hath gone down thither a little while since, and which is still at the gate of hell."

Cultural references[edit]

- The witch appears as a character in oratorios (including Mors Saulis et Jonathae (c. 1682) by Charpentier, In Guilty Night: Saul and the Witch of Endor (1691) by Henry Purcell, Saul (1738) by George Frideric Handel on the death of Saul, and Le Roi David (1921) by Honegger), in dance music (The Witch of Endor (1969) by Louis Hardin) and operas (David et Jonathas (1688) by the afore-mentioned Charpentier and Saul og David (1902) by Carl Nielsen).

- A year after the death of his son at Loos, Rudyard Kipling wrote a poem called "En-Dor" (1919), about supposed communication with the dead.[23] It concludes,

Oh the road to En-dor is the oldest road

And the craziest road of all!

Straight it runs to the Witch’s abode,

As it did in the days of Saul,

And nothing has changed of the sorrow in store

For such as go down on the road to En-dor!

- The Martha Graham Dance Company premiered The Witch of Endor in 1965 at the 54th Street Theater in New York. A one-act work, it had choreography and costumes by Martha Graham, music by William Schuman, sets by Ming Cho Lee, and lighting by Jean Rosenthal.

- In Endor by Shaul Tchernichovsky, describing King Saul's encounter with the Witch of Endor, is considered a major work of modern Hebrew poetry. Tchernichovsky particularly identified with the character of Saul, perhaps due to his own name, and the poem expresses considerable empathy to this King's tragic fate.

- An episode in the 1932 radio program NBC Mystery Serial written by Carlton E. Morse was called The Witch of Endor, and included a character who said she was a witch; the story was set in "a sparsely populated residential district in the suburbs of San Francisco called Endor Park".[24][25]

- A ship named the Witch of Endor was also featured in the Horatio Hornblower book "Flying Colours". The cutter, with an armament of 10 guns, was used by Hornblower to escape from France after he was captured.

- The Witch of Endor is a ship in Babylon's Ashes, the sixth book of The Expanse series by James S. A. Corey. She is destroyed early in book six on the orders of Marco Inaros, chief antagonist of the books five and six (Nemesis Games and Babylon's Ashes) for mutiny.[26]

- Endora from the hit TV series Bewitched was named after the Witch of Endor to appease Christians who may otherwise have been critical of the program's occult themes.[citation needed]

- Massachusetts playwright Jon Lipsky's 1978 play Beginner's Luck is based on King Saul's encounter with the Witch of Endor in the Bible.[27]

- "Witch of Endor" is the first track on the self-titled 2012 debut album of American occult rock band Bloody Hammers.

- The Witch of Endor is a modern day character in Michael Scott's novel, "The Alchemist: The Secrets of the Immortal Nicholas Flamel." (2007,Delacourt Press) In it, she is described as "not just a witch. She is the original Witch."

- “Lover, Leaver (Taker, Believer)”, featured as the fifth track on the modern rock band Greta Van Fleet’s 2018 debut album Anthem of the Peaceful Army, references the Biblical tale of the Witch of Endor.

Oh God, hellfire

Witch of Endor raised

Saul would fall to his knees,

Watch the fire blaze

Satan plays his flute for him

The sound, it burns his ears

Watches as the peace of man

Slips and disappears

Dramatic representations[edit]

- The Witch of Endor was portrayed by Israeli actor Dov Reiser in the 1976 American television film The Story of David.

- The Witch of Endor was portrayed by Belgian actress Lyne Renée in the 2016 American television series Of Kings and Prophets.

References[edit]

- ^ Barton, John; Muddiman, John, eds. (2007). The Oxford Bible Commentary. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978- 0199277186.

- ^ 1 Samuel 28:3-25

- ^ Hoffner, Harry A. (1967). "Second Millenium Antecedents to the Hebrew 'Ôḇ". Journal of Biblical Literature. Atlanta, Georgia: Society of Biblical Literature. 86 (4): 385–401. doi:10.2307/3262793. JSTOR 3262793.

- ^ King, Philip J.; Stager, Lawrence E. (2001). Life in Biblical Israel. Louisville, Kentucky: Westminster John Knox Press. p. 380. ISBN 9780664221485.

- ^ a b Hirsh, Emil G. (1911). "Endor, the witch of". Jewish Encyclopedia.

- ^ Aune, D. E. (1959). "Medium". In Bromiley, Geoffrey W. (ed.). The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia. p. 307.

... of 'ob (RSV 'medium'). According to one view it is the same word that means a 'bottle made out of skins' ('wineskin,' Job 32:19). The term would then refer to the technique of ventriloquism or, more accurately, 'belly-talking'.

- ^ Walton, John H. (November 1, 2006). Ancient Near Eastern Thought and the Old Testament: Introducing the Conceptual World of the Hebrew Bible. Ada, Michigan: Baker Academic. ISBN 9781585582914.

- ^ Geza Vermes (2008) The Resurrection. London, Penguin: 25–6

- ^ Beuken, Willem. "I Samuel 28: The Prophet as "Hammer of Witches"." Journal for the Study of the Old Testament 3.6 (1978): 8-9.

- ^ Keil, Carl Friedrich, and Franz Delitzsch. Biblical Commentary on the Books of Samuel. Eerdmans, 1956, 262.

- ^ Baldwin, Joyce. 1 and 2 Samuel: An Introduction and Commentary. 1989, 159.

- ^ Die Bibel - nach Martin Luthers Übersetzung, Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft, Stuttgart 1985, p. 316

- ^ Yalḳ, Sam. 140, from Pirḳe R. El.

- ^ Calmet, Augustin. Treatise on the Apparitions of Spirits and on Vampires or Revenants: of Hungary, Moravia, et al. The Complete Volumes I & II. 2016. p. 47;237. ISBN 978-1-5331-4568-0.

- ^ Klauck, Hans-Josef; McNeil, Brian (2003). Magic and Paganism in early Christianity: the world of the Acts of the Apostles. p. 66.

A classical example is King Saul's visit to the witch of Endor: The Septuagint says once that the seer engages in soothsaying and three times that she engages in ventriloquism (1 Sam 28:6–9).

- ^ Andreasen, Milian Lauritz (2001). Isaiah the gospel prophet: A preacher of righteousness. p. 345.

The Septuagint translates: They burn incense on bricks to devils which exist not.

- ^ King James (2016). Annotated Daemonologie. A critical edition in modern English. pp. 9–10. ISBN 1-5329-6891-4.

- ^ King James (2016). Annotated Daemonologie. A critical edition in modern English. p. 9. ISBN 1-5329-6891-4.

- ^ "Necromancy". Catholic Encyclopedia. Retrieved 5 Sep 2012.

- ^ Buckley, J.M. (2003). Faith Healing, Christian Science and Kindred Phenomena. p. 221.

The witch of Endor – The account of the "Witch of Endor" is the only instance in the Bible where a description of the processes and ... Luther held that it was "the Devil's ghost"; Calvin that "it was not the real Samuel, but a spectre".

- ^ "The Religion of Ghosts". Spiritualist at Work. 1 (19). Chicago. 24 April 1875. p. 1.

- ^ Calmet, Augustin (2016). Traité sur les apparitions des esprits et sur les vampires ou les revenans de Hongrie, de Moravie, &c. [Treatise on the Apparitions of Spirits and on Vampires or Revenants: of Hungary, Moravia, etc.]. I & II. p. 237. ISBN 978-1-5331-4568-0.

- ^ Tonie Holt, Valmai Holt My Boy Jack: The Search for Kipling's Only Son (1998), p. 234. "Desperate as they were, there is no evidence that Rudyard and Carrie ever contemplated trying to reach John in this way and Rudyard's scorn for those who did was expressed in the poem En-dor, written the following year."

- ^ "Today's Radio Program". San Bernardino Sun via the California Digital Newspaper Collection. 18 April 1932. p. 5.

- ^ "Radio history of The NBC Mystery Theater". RadioHorrorHosts.com. Retrieved 23 January 2017.

- ^ Corey, James S. A. (2016). Babylon's Ashes. Orbit. p. 305. ISBN 978-0-316-21763-7.

- ^ A Short Biography of Jon Lipsky, written by Jonah Lipsky for The Plays of Jon Lipsky: A Two-volume Collection

Further reading[edit]

- Greer, R.A.; Mitchell, M.M. (2007). The "Belly-Myther" of Endor: Interpretations of 1 Kingdoms 28 in the Early Church. Society of Biblical Literature writings from the Greco-Roman world. Society of Biblical Literature. ISBN 978-1-58983-120-9.

External links[edit]

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Witch of Endor. |

- Medium of Endor: From the Jewish Encyclopedia