Codex Atlanticus

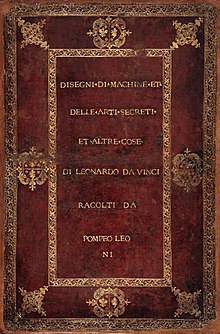

The Codex Atlanticus (Atlantic Codex) is a twelve-volume, bound set of drawings and writings (in Italian) by Leonardo da Vinci, the largest such set; its name indicates the large paper used to preserve original Leonardo notebook pages, which was that used for atlases. It comprises 1,119 leaves dating from 1478 to 1519, the contents covering a great variety of subjects, from flight to weaponry to musical instruments and from mathematics to botany. This codex was gathered in the late 16th century by the sculptor Pompeo Leoni, who dismembered some of Leonardo's notebooks in its formation. It is currently preserved at the Biblioteca Ambrosiana in Milan.

Contents[edit]

The folios in the Codex Atlanticus deal with various subjects ranging from mechanics to hydraulics, from studies and sketches for paintings to mathematics and astronomy, from philosophical meditations to fables, all the way to curious inventions such as parachutes, war machineries and hydraulic pumps.[1]

Hoist by Leonardo da Vinci (Codex Atlanticus, f. 30v., 1480 ca.). Reconstruction at the Museo nazionale della scienza e della tecnologia Leonardo da Vinci, Milan.

History[edit]

Leonardo composed the 1,119 leaves later collected in the Codex Atlanticus from 1478 to 1519.[2] His notebooks—originally loose papers of different types and sizes, were largely entrusted to his pupil and heir Francesco Melzi after the master's death.[3] These were to be published, a task of overwhelming difficulty because of its scope and Leonardo's idiosyncratic writing.[4] After Melzi's death in 1570, the collection passed to his son, the lawyer Orazio, who initially took little interest in the journals.[3] In 1587, a Melzi household tutor named Lelio Gavardi took 13 of the manuscripts to Florence, intending to offer them to the grand duke of Tuscany. However, following Francesco I de' Medici's untimely death, Gavardi took them to Pisa to give to his relative Aldus Manutius the Younger; there, Giovanni Magenta reproached Gavardi for having taken the manuscripts illicitly and returned them to Orazio. Having many more such works in his possession, Orazio gifted the 13 volumes to Magenta. News spread of these lost works of Leonardo's, and Orazio retrieved seven of the 13 manuscripts, which he then gave to Pompeo Leoni for publication in two volumes; one of these was the Codex Atlanticus.[5] Leoni dismembered some of Leonardo's notebooks in the formation of the codex, gathering the original leaves into 1,222 pages.[2]

When Napoleon conquered Milan in 1796, he seized about a dozen Leonardo manuscripts including the Codex and sent them to Paris, saying that "all men of genius ... are French, whatever the country which has given them birth." The manuscript was returned to Milan at the end of the Napoleonic Wars, but the other manuscripts remain in the Paris Institut de France.[2]

The codex was restored and rebound by the Basilian monks working in the Laboratory for the Restoration of Ancient Books and Manuscripts of the Exarchic Greek Abbey of St. Mary of Grottaferrata from 1968 to 1972.[6]

In April 2006, Carmen Bambach of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City discovered an extensive invasion of molds of various colors, including black, red, and purple, along with swelling of pages.[7][8] Monsignor Gianfranco Ravasi—then the head of the Ambrosian Library, now head of the Pontifical Council for Culture at the Vatican—alerted the Italian conservation institute, the Opificio delle Pietre Dure, in Florence. In October 2008, it was determined that the colors found on the pages were not the product of mold, but were instead caused by mercury salts added to protect the Codex from mold.[9] Moreover, the staining appears to be not on the codex but on later cartonage.[10]

In 2019, an interactive website has been launched that allows exploration of the Codex Atlanticus in its entirety and to organize its 1,119 pages by subject, year and page number.

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ "Codex Atlanticus". Archived from the original on October 6, 2018. Retrieved March 11, 2014.

- ^ a b c Wallace, Robert (1972) [1966]. The World of Leonardo: 1452–1519. New York: Time-Life Books. p. 170.

- ^ a b Wallace 1972, p. 169.

- ^ Keele Kenneth D (1964). "Leonardo da Vinci's Influence on Renaissance Anatomy". Med Hist. 8 (4): 360–70. doi:10.1017/s0025727300029835. PMC 1033412. PMID 14230140.

- ^ Major, Richard Henry (1866). Archaeologia: Or Miscellaneous Tracts Relating to Antiquity, Volume 40, Part 1. London: The Society. pp. 15–16.

- ^ "Official web site of the Abbey of St. Mary of Grottaferrata". Abbaziagreca.it. Retrieved 2013-07-17.

- ^ AP via N.Y. Times story of mold damage and history

- ^ "Codex Atlanticus by Leonardo Da Vinci is being damaged by mould". Entertainment.timesonline.co.uk. Retrieved 2013-07-17.

- ^ "Study: Da Vinci Codex old but not moldy". Physorg.com. 2008-10-21. Retrieved 2013-07-17.

- ^ AP story via Yahoo, Oct. 21, 2008 Archived October 26, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

External links[edit]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Codex Atlanticus. |

- Browsable online archive of digitized images of the Codex Atlanticus at Biblioteca Leonardiana (e-Leo)

- Reconstruction of the original Da Vinci's Codex Atlanticus