Flerovium

| Flerovium | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /flɪˈroʊviəm/[1] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mass number | [289] (unconfirmed: 290) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Flerovium in the periodic table | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic number (Z) | 114 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Group | group 14 (carbon group) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Period | period 7 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Block | p-block | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Element category | Unknown chemical properties, but probably a post-transition metal; possibly a metalloid[2] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electron configuration | [Rn] 5f14 6d10 7s2 7p2 (predicted)[3] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrons per shell | 2, 8, 18, 32, 32, 18, 4 (predicted) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Physical properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Phase at STP | gas (predicted)[3] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Boiling point | ~ 210 K (~ −60 °C, ~ −80 °F) [4][5] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Density when liquid (at m.p.) | 14 g/cm3 (predicted)[6] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heat of vaporization | 38 kJ/mol (predicted)[6] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Oxidation states | (0), (+1), (+2), (+4), (+6) (predicted)[3][6][7] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ionization energies | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic radius | empirical: 180 pm (predicted)[3][6] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Covalent radius | 171–177 pm (extrapolated)[9] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Natural occurrence | synthetic | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Crystal structure | face-centred cubic (fcc) (predicted)[10] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| CAS Number | 54085-16-4 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Naming | after Flerov Laboratory of Nuclear Reactions (itself named after Georgy Flyorov)[11] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Discovery | Joint Institute for Nuclear Research (JINR) and Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL) (1999) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Main isotopes of flerovium | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Flerovium is a superheavy artificial chemical element with the symbol Fl and atomic number 114. It is an extremely radioactive synthetic element. The element is named after the Flerov Laboratory of Nuclear Reactions of the Joint Institute for Nuclear Research in Dubna, Russia, where the element was discovered in 1998. The name of the laboratory, in turn, honours the Russian physicist Georgy Flyorov (Флёров in Cyrillic, hence the transliteration of "yo" to "e"). The name was adopted by IUPAC on 30 May 2012.

In the periodic table of the elements, it is a transactinide element in the p-block. It is a member of the 7th period and is the heaviest known member of the carbon group; it is also the heaviest element whose chemistry has been investigated. Initial chemical studies performed in 2007–2008 indicated that flerovium was unexpectedly volatile for a group 14 element;[18] in preliminary results it even seemed to exhibit properties similar to those of the noble gases.[19] More recent results show that flerovium's reaction with gold is similar to that of copernicium, showing that it is a very volatile element that may even be gaseous at standard temperature and pressure, that it would show metallic properties, consistent with it being the heavier homologue of lead, and that it would be the least reactive metal in group 14. The question of whether flerovium behaves more like a metal or a noble gas is still unresolved as of 2018.

About 90 atoms of flerovium have been observed: 58 were synthesized directly, and the rest were made from the radioactive decay of heavier elements. All of these flerovium atoms have been shown to have mass numbers from 284 to 290. The most stable known flerovium isotope, flerovium-289, has a half-life of around 1.9 seconds, but it is possible that the unconfirmed flerovium-290 with one extra neutron may have a longer half-life of 19 seconds; this would be one of the longest half-lives of any isotope of any element at these farthest reaches of the periodic table. Flerovium is predicted to be near the centre of the theorized island of stability, and it is expected that heavier flerovium isotopes, especially the possibly doubly magic flerovium-298, may have even longer half-lives.

Introduction[edit]

A superheavy[a] atomic nucleus is created in a nuclear reaction that combines two other nuclei of unequal size[b] into one; roughly, the more unequal the two nuclei in terms of mass, the greater the possibility that the two react.[25] The material made of the heavier nuclei is made into a target, which is then bombarded by the beam of lighter nuclei. Two nuclei can only fuse into one if they approach each other closely enough; normally, nuclei (all positively charged) repel each other due to electrostatic repulsion. The strong interaction can overcome this repulsion but only within a very short distance from a nucleus; beam nuclei are thus greatly accelerated in order to make such repulsion insignificant compared to the velocity of the beam nucleus.[26] Coming close alone is not enough for two nuclei to fuse: when two nuclei approach each other, they usually remain together for approximately 10−20 seconds and then part ways (not necessarily in the same composition as before the reaction) rather than form a single nucleus.[26][27] If fusion does occur, the temporary merger—termed a compound nucleus—is an excited state. To lose its excitation energy and reach a more stable state, a compound nucleus either fissions or ejects one or several neutrons,[c] which carry away the energy. This occurs in approximately 10−16 seconds after the initial collision.[28][d]

The beam passes through the target and reaches the next chamber, the separator; if a new nucleus is produced, it is carried with this beam.[31] In the separator, the newly produced nucleus is separated from other nuclides (that of the original beam and any other reaction products)[e] and transferred to a surface-barrier detector, which stops the nucleus. The exact location of the upcoming impact on the detector is marked; also marked are its energy and the time of the arrival.[31] The transfer takes about 10−6 seconds; in order to be detected, the nucleus must survive this long.[34] The nucleus is recorded again once its decay is registered, and the location, the energy, and the time of the decay are measured.[31]

Stability of a nucleus is provided by the strong interaction. However, its range is very short; as nuclei become larger, its influence on the outermost nucleons (protons and neutrons) weakens. At the same time, the nucleus is torn apart by electrostatic repulsion between protons, as it has unlimited range.[35] Superheavy nuclei are thus theoretically predicted[36] and have so far been observed[37] to predominantly decay via decay modes that are caused by such repulsion: alpha decay and spontaneous fission.[f] Alpha decays are registered by the emitted alpha particles, and the decay products are easy to determine before the actual decay; if such a decay or a series of consecutive decays produces a known nucleus, the original product of a reaction can be easily determined.[g] Spontaneous fission, however, produces various nuclei as products, so the original nuclide cannot be determined from its daughters.[h]

The information available to physicists aiming to synthesize a superheavy element is thus the information collected at the detectors: location, energy, and time of arrival of a particle to the detector, and those of its decay. The physicists analyze this data and seek to conclude that it was indeed caused by a new element and could not have been caused by a different nuclide than the one claimed. Often, provided data is insufficient for a conclusion that a new element was definitely created and there is no other explanation for the observed effects; errors in interpreting data have been made.[i]History[edit]

Pre-discovery[edit]

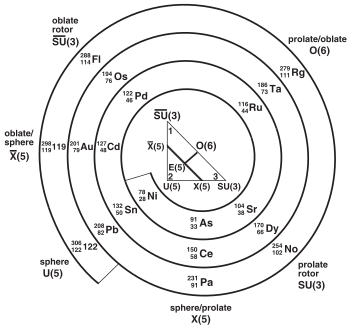

From the late 1940s to the early 1960s, the early days of the synthesis of heavier and heavier transuranium elements, it was predicted that since such heavy elements did not occur naturally, they would have shorter and shorter half-lives to spontaneous fission, until they stopped existing altogether at around element 108 (now known as hassium). Initial work in the synthesis of the actinides appeared to confirm this.[49] The nuclear shell model, introduced in 1949 and extensively developed in the late 1960s by William Myers and Władysław Świątecki, stated that the protons and neutrons formed shells within a nucleus, somewhat analogous to electrons forming electron shells within an atom. The noble gases are unreactive due to their having full electron shells; thus it was theorized that elements with full nuclear shells – having so-called "magic" numbers of protons or neutrons – would be stabilized against radioactive decay. A doubly magic isotope, having magic numbers of both protons and neutrons, would be especially stabilized. Heiner Meldner calculated in 1965 that the next doubly magic isotope after lead-208 would be flerovium-298 with 114 protons and 184 neutrons, which would form the centre of a so-called "island of stability".[49][50] This island of stability, supposedly ranging from copernicium (element 112) to oganesson (118), would come after a long "sea of instability" from elements 101 (mendelevium) to 111 (roentgenium),[49] and the flerovium isotopes in it were speculated in 1966 to have half-lives in excess of a hundred million years.[51] These early predictions fascinated researchers, and led to the first attempted synthesis of flerovium in 1968 using the reaction 248Cm(40Ar,xn). No isotopes of flerovium were found in this reaction. This was thought to occur because the compound nucleus 288Fl only has 174 neutrons instead of the hypothesized magic 184, and this would have a significant impact on the reaction cross section (yield) and the half-lives of nuclei produced.[52][53] It then took thirty more years for the first isotopes of flerovium to be synthesized.[49] More recent work suggests that the local islands of stability around hassium and flerovium are due to these nuclei being respectively deformed and oblate, which make them resistant to spontaneous fission, and that the true island of stability for spherical nuclei occurs at around unbibium-306 (with 122 protons and 184 neutrons).[54]

Discovery[edit]

Flerovium was first synthesized in December 1998 by a team of scientists at the Joint Institute for Nuclear Research (JINR) in Dubna, Russia, led by Yuri Oganessian, who bombarded a target of plutonium-244 with accelerated nuclei of calcium-48:

- 244

94Pu

+ 48

20Ca

→ 292

114Fl

* → 290

114Fl

+ 2 1

0n

This reaction had been attempted before, but without success; for this 1998 attempt, the JINR had upgraded all of its equipment to detect and separate the produced atoms better and bombard the target more intensely.[55] A single atom of flerovium, decaying by alpha emission with a lifetime of 30.4 seconds, was detected. The decay energy measured was 9.71 MeV, giving an expected half-life of 2–23 s.[56] This observation was assigned to the isotope flerovium-289 and was published in January 1999.[56] The experiment was later repeated, but an isotope with these decay properties was never found again and hence the exact identity of this activity is unknown. It is possible that it was due to the metastable isomer 289mFl,[57][58] but because the presence of a whole series of longer-lived isomers in its decay chain would be rather doubtful, the most likely assignment of this chain is to the 2n channel leading to 290Fl and electron capture to 290Nh, which fits well with the systematics and trends across flerovium isotopes, and is consistent with the low beam energy that was chosen for that experiment, although further confirmation would be desirable via the synthesis of 294Lv in the 248Cm(48Ca,2n) reaction, which would alpha decay to 290Fl.[16] The team at RIKEN reported a possible synthesis of the isotopes 294Lv and 290Fl in 2016 through the 248Cm(48Ca,2n) reaction, but the alpha decay of 294Lv was missed, alpha decay of 290Fl to 286Cn was observed instead of electron capture to 290Nh, and the assignment to 294Lv instead of 293Lv and decay to an isomer of 285Cn was not certain.[17]

Glenn T. Seaborg, a scientist at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory who had been involved in work to synthesize such superheavy elements, had said in December 1997 that "one of his longest-lasting and most cherished dreams was to see one of these magic elements";[49] he was told of the synthesis of flerovium by his colleague Albert Ghiorso soon after its publication in 1999. Ghiorso later recalled:[59]

I wanted Glenn to know, so I went to his bedside and told him. I thought I saw a gleam in his eye, but the next day when I went to visit him he didn't remember seeing me. As a scientist, he had died when he had that stroke.[59]

— Albert Ghiorso

Seaborg died two months later, on 25 February 1999.[59]

Isotopes[edit]

| Isotope | Half-life[j] | Decay mode |

Discovery year[60] |

Discovery reaction[61] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Value | Ref | ||||

| 284Fl | 2.5 ms | [13] | SF | 2015 | 240Pu(48Ca,4n) 239Pu(48Ca,3n) |

| 285Fl | 0.10 s | [14] | α | 2010 | 242Pu(48Ca,5n) |

| 286Fl | 0.12 s | [62] | α, SF | 2003 | 290Lv(—,α) |

| 287Fl | 0.48 s | [62] | α, EC? | 2003 | 244Pu(48Ca,5n) |

| 288Fl | 0.66 s | [62] | α | 2004 | 244Pu(48Ca,4n) |

| 289Fl | 1.9 s | [62] | α | 1999 | 244Pu(48Ca,3n) |

| 289mFl[k] | 1.1 s | [60] | α | 2012 | 293mLv(—,α) |

| 290Fl[l] | 19 s | [16][17] | α, EC? | 1998 | 244Pu(48Ca,2n) |

In March 1999, the same team replaced the 244Pu target with a 242Pu one in order to produce other flerovium isotopes. In this reaction, two atoms of flerovium were produced, decaying via alpha emission with a half-life of 5.5 s. They were assigned as 287Fl.[63] This activity has not been seen again either, and it is unclear what nucleus was produced. It is possible that it was the meta-stable isomer 287mFl[64] or the result of an electron capture branch of 287Fl leading to 287Nh and 283Rg.[15]

The now-confirmed discovery of flerovium was made in June 1999 when the Dubna team repeated the first reaction from 1998. This time, two atoms of flerovium were produced; they alpha decayed with a half-life of 2.6 s, different from the 1998 result.[57] This activity was initially assigned to 288Fl in error, due to the confusion regarding the previous observations that were assumed to come from 289Fl. Further work in December 2002 finally allowed a positive reassignment of the June 1999 atoms to 289Fl.[64]

In May 2009, the Joint Working Party (JWP) of IUPAC published a report on the discovery of copernicium in which they acknowledged the discovery of the isotope 283Cn.[65] This implied the discovery of flerovium, from the acknowledgement of the data for the synthesis of 287Fl and 291Lv, which decay to 283Cn. The discovery of the isotopes flerovium-286 and -287 was confirmed in January 2009 at Berkeley. This was followed by confirmation of flerovium-288 and -289 in July 2009 at the Gesellschaft für Schwerionenforschung (GSI) in Germany. In 2011, IUPAC evaluated the Dubna team experiments of 1999–2007. They found the early data inconclusive, but accepted the results of 2004–2007 as flerovium, and the element was officially recognized as having been discovered.[66]

While the method of chemical characterisation of a daughter was successful in the cases of flerovium and livermorium, and the simpler structure of even–even nuclei made the confirmation of oganesson (element 118) straightforward, there have been difficulties in establishing the congruence of decay chains from isotopes with odd protons, odd neutrons, or both.[67][68] To get around this problem with hot fusion, the decay chains from which terminate in spontaneous fission instead of connecting to known nuclei as cold fusion allows, experiments were performed at Dubna in 2015 to produce lighter isotopes of flerovium in the reactions of 48Ca with 239Pu and 240Pu, particularly 283Fl, 284Fl, and 285Fl; the last had previously been characterised in the 242Pu(48Ca,5n)285Fl reaction at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory in 2010. The isotope 285Fl was more clearly characterised, while the new isotope 284Fl was found to undergo immediate spontaneous fission instead of alpha decay to known nuclides around the N = 162 shell closure, and 283Fl was not found.[13] This lightest isotope may yet conceivably be produced in the cold fusion reaction 208Pb(76Ge,n)283Fl,[16] which the team at RIKEN in Japan has considered investigating:[69][70] this reaction is expected to have a higher cross-section of 200 fb than the "world record" low of 30 fb for 209Bi(70Zn,n)278Nh, the reaction which RIKEN used for the official discovery of element 113, now named nihonium.[16][71][72] The Dubna team repeated their investigation of the 240Pu+48Ca reaction in 2017, observing three new consistent decay chains of 285Fl, an additional decay chain from this nuclide that may pass through some isomeric states in its daughters, a chain that could be assigned to 287Fl (likely stemming from 242Pu impurities in the target), and some spontaneous fission events of which some could be from 284Fl, though other interpretations including side reactions involving the evaporation of charged particles are also possible.[14]

Naming[edit]

Using Mendeleev's nomenclature for unnamed and undiscovered elements, flerovium is sometimes called eka-lead. In 1979, IUPAC published recommendations according to which the element was to be called ununquadium (with the corresponding symbol of Uuq),[73] a systematic element name as a placeholder, until the discovery of the element is confirmed and a permanent name is decided on. Most scientists in the field called it "element 114", with the symbol of E114, (114) or 114.[3]

According to IUPAC recommendations, the discoverer(s) of a new element has the right to suggest a name.[74] After the discovery of flerovium and livermorium was recognized by IUPAC on 1 June 2011, IUPAC asked the discovery team at the JINR to suggest permanent names for those two elements. The Dubna team chose to name element 114 flerovium (symbol Fl),[75][76] after the Russian Flerov Laboratory of Nuclear Reactions (FLNR), named after the Soviet physicist Georgy Flyorov (also spelled Flerov); earlier reports claim the element name was directly proposed to honour Flyorov.[77] In accordance with the proposal received from the discoverers IUPAC officially named flerovium after the Flerov Laboratory of Nuclear Reactions (an older name for the JINR), not after Flyorov himself.[11] Flyorov is known for writing to Joseph Stalin in April 1942 and pointing out the silence in scientific journals in the field of nuclear fission in the United States, Great Britain, and Germany. Flyorov deduced that this research must have become classified information in those countries. Flyorov's work and urgings led to the development of the USSR's own atomic bomb project.[76] Flyorov is also known for the discovery of spontaneous fission with Konstantin Petrzhak. The naming ceremony for flerovium and livermorium was held on 24 October 2012 in Moscow.[78]

In a 2015 interview with Oganessian, the host, in preparation to ask a question, said, "You said you had dreamed to name [an element] after your teacher Georgy Flyorov." Without letting the host finish, Oganessian repeatedly said, "I did."[79]

Predicted properties[edit]

Very few properties of flerovium or its compounds have been measured; this is due to its extremely limited and expensive production[25] and the fact that it decays very quickly. A few singular properties have been measured, but for the most part, properties of flerovium remain unknown and only predictions are available.

Nuclear stability and isotopes[edit]

The physical basis of the chemical periodicity governing the periodic table is the electron shell closures at each noble gas (atomic numbers 2, 10, 18, 36, 54, 86, and 118): as any further electrons must enter a new shell with higher energy, closed-shell electron configurations are markedly more stable, leading to the relative inertness of the noble gases.[6] Since protons and neutrons are also known to arrange themselves in closed nuclear shells, the same effect happens at nucleon shell closures, which happen at specific nucleon numbers often dubbed "magic numbers". The known magic numbers are 2, 8, 20, 28, 50, and 82 for protons and neutrons, and additionally 126 for neutrons.[6] Nucleons with magic proton and neutron numbers, such as helium-4, oxygen-16, calcium-48, and lead-208, are termed "doubly magic" and are very stable against decay. This property of increased nuclear stability is very important for superheavy elements: without any stabilization, their half-lives would be expected by exponential extrapolation to be in the range of nanoseconds (10−9 s) when element 110 (darmstadtium) is reached, because of the ever-increasing repulsive electrostatic forces between the positively charged protons that overcome the limited-range strong nuclear force that holds the nucleus together. The next closed nucleon shells and hence magic numbers are thought to denote the centre of the long-sought island of stability, where the half-lives to alpha decay and spontaneous fission lengthen again.[6]

Initially, by analogy with the neutron magic number 126, the next proton shell was also expected to occur at element 126, too far away from the synthesis capabilities of the mid-20th century to achieve much theoretical attention. In 1966, new values for the potential and spin-orbit interaction in this region of the periodic table[80] contradicted this and predicted that the next proton shell would occur instead at element 114,[6] and that nuclides in this region would be as stable against spontaneous fission as many heavy nuclei such as lead-208.[6] The expected closed neutron shells in this region were at neutron number 184 or 196, thus making 298Fl and 310Fl candidates for being doubly magic.[6] 1972 estimates predicted a half-life of about a year for 298Fl, which was expected to be near a large island of stability with the longest half-life at 294Ds (1010 years, comparable to that of 232Th).[6] After the synthesis of the first isotopes of elements 112 through 118 at the turn of the 21st century, it was found that the synthesized neutron-deficient isotopes were stabilized against fission. In 2008 it was thus hypothesized that the stabilization against fission of these nuclides was due to their being oblate nuclei, and that a region of oblate nuclei was centred on 288Fl. Additionally, new theoretical models showed that the expected gap in energy between the proton orbitals 2f7/2 (filled at element 114) and 2f5/2 (filled at element 120) was smaller than expected, so that element 114 no longer appeared to be a stable spherical closed nuclear shell. The next doubly magic nucleus is now expected to be around 306Ubb, but the expected low half-life and low production cross section of this nuclide makes its synthesis challenging.[54] Nevertheless, the island of stability is still expected to exist in this region of the periodic table, and nearer its centre (which has not been approached closely enough yet) some nuclides, such as 291Mc and its alpha- and beta-decay daughters,[m] may be found to decay by positron emission or electron capture and thus move into the centre of the island.[71] Due to the expected high fission barriers, any nucleus within this island of stability decays exclusively by alpha decay and perhaps some electron capture and beta decay,[6] both of which would bring the nuclei closer to the beta stability line where the island is expected to be. Electron capture is needed to reach the island, which is problematic because it is not certain that electron capture becomes a major decay mode in this region of the chart of nuclides.[71]

Several experiments have been performed between 2000 and 2004 at the Flerov Laboratory of Nuclear Reactions in Dubna studying the fission characteristics of the compound nucleus 292Fl by bombarding a plutonium-244 target with accelerated calcium-48 ions.[81] A compound nucleus is a loose combination of nucleons that have not yet arranged themselves into nuclear shells. It has no internal structure and is held together only by the collision forces between the target and projectile nuclei.[82][n] The results revealed how nuclei such as this fission predominantly by expelling doubly magic or nearly doubly magic fragments such as calcium-40, tin-132, lead-208, or bismuth-209. It was also found that the yield for the fusion-fission pathway was similar between calcium-48 and iron-58 projectiles, indicating a possible future use of iron-58 projectiles in superheavy element formation.[81] It has also been suggested that a neutron-rich flerovium isotope can be formed by the quasifission (partial fusion followed by fission) of a massive nucleus.[83] Recently it has been shown that the multi-nucleon transfer reactions in collisions of actinide nuclei (such as uranium and curium) might be used to synthesize the neutron-rich superheavy nuclei located at the island of stability,[83] although production of neutron-rich nobelium or seaborgium nuclei is more likely.[71]

Theoretical estimation of the alpha decay half-lives of the isotopes of the flerovium supports the experimental data.[84][85] The fission-survived isotope 298Fl, long expected to be doubly magic, is predicted to have alpha decay half-life around 17 days.[86][87] The direct synthesis of the nucleus 298Fl by a fusion–evaporation pathway is currently impossible since no known combination of target and stable projectile can provide 184 neutrons in the compound nucleus, and radioactive projectiles such as calcium-50 (half-life fourteen seconds) cannot yet be used in the needed quantity and intensity.[83] Currently, one possibility for the synthesis of the expected long-lived nuclei of copernicium (291Cn and 293Cn) and flerovium near the middle of the island include using even heavier targets such as curium-250, berkelium-249, californium-251, and einsteinium-254, that when fused with calcium-48 would produce nuclei such as 291Mc and 291Fl (as decay products of 299Uue, 295Ts, and 295Lv), with just enough neutrons to alpha decay to nuclides close enough to the centre of the island to possibly undergo electron capture and move inwards to the centre, though the cross sections would be small and little is yet known about the decay properties of superheavy nuclides near the beta stability line. This may be the best hope currently to synthesize nuclei on the island of stability, but it is speculative and may or may not work in practice.[71] Another possibility is to use controlled nuclear explosions to achieve the high neutron flux necessary to create macroscopic amounts of such isotopes.[71] This would mimic the r-process in which the actinides were first produced in nature and the gap of instability after polonium bypassed, as it would bypass the gaps of instability at 258–260Fm and at mass number 275 (atomic numbers 104 to 108).[71] Some such isotopes (especially 291Cn and 293Cn) may even have been synthesized in nature, but would have decayed away far too quickly (with half-lives of only thousands of years) and be produced in far too small quantities (about 10−12 the abundance of lead) to be detectable as primordial nuclides today outside cosmic rays.[71]

Atomic and physical[edit]

Flerovium is a member of group 14 in the periodic table, below carbon, silicon, germanium, tin, and lead. Every previous group 14 element has four electrons in its valence shell, forming a valence electron configuration of ns2np2. In flerovium's case, the trend will be continued and the valence electron configuration is predicted to be 7s27p2;[3] flerovium will behave similarly to its lighter congeners in many respects. Differences are likely to arise; a largely contributing effect is the spin–orbit (SO) interaction—the mutual interaction between the electrons' motion and spin. It is especially strong for the superheavy elements, because their electrons move faster than in lighter atoms, at velocities comparable to the speed of light.[88] In relation to flerovium atoms, it lowers the 7s and the 7p electron energy levels (stabilizing the corresponding electrons), but two of the 7p electron energy levels are stabilized more than the other four.[89] The stabilization of the 7s electrons is called the inert pair effect, and the effect "tearing" the 7p subshell into the more stabilized and the less stabilized parts is called subshell splitting. Computation chemists see the split as a change of the second (azimuthal) quantum number l from 1 to 1⁄2 and 3⁄2 for the more stabilized and less stabilized parts of the 7p subshell, respectively.[90][o] For many theoretical purposes, the valence electron configuration may be represented to reflect the 7p subshell split as 7s2

7p2

1/2.[3] These effects cause flerovium's chemistry to be somewhat different from that of its lighter neighbours.

Due to the spin-orbit splitting of the 7p subshell being very large in flerovium, and the fact that both flerovium's filled orbitals in the seventh shell are stabilized relativistically, the valence electron configuration of flerovium may be considered to have a completely filled shell. Its first ionization energy of 8.539 eV (823.9 kJ/mol) should be the second-highest in group 14.[3] The 6d electron levels are also destabilized, leading to some early speculations that they may be chemically active, although newer work suggests that this is unlikely.[6] Because this first ionisation energy is higher than that of silicon and germanium, though still lower than that for carbon, it has been suggested that flerovium could be classified as a metalloid.[2]

The closed-shell electron configuration of flerovium results in the metallic bonding in metallic flerovium being weaker than in the preceding and following elements; thus, flerovium is expected to have a low boiling point,[3] and has recently been suggested to be possibly a gaseous metal, similar to the predictions for copernicium, which also has a closed-shell electron configuration.[54] The melting and boiling points of flerovium were predicted in the 1970s to be around 70 °C and 150 °C,[3] significantly lower than the values for the lighter group 14 elements (those of lead are 327 °C and 1749 °C respectively), and continuing the trend of decreasing boiling points down the group. Although earlier studies predicted a boiling point of ~1000 °C or 2840 °C,[6] this is now considered unlikely because of the expected weak metallic bonding in flerovium and that group trends would expect flerovium to have a low sublimation enthalpy.[3] Recent experimental indications have suggested that the pseudo-closed shell configuration of flerovium results in very weak metallic bonding and hence that flerovium is probably a gas at room temperature with a boiling point of around −60 °C.[4] Like mercury, radon, and copernicium, but not lead and oganesson (eka-radon), flerovium is calculated to have no electron affinity.[91]

In the solid state, flerovium is expected to be a dense metal due to its high atomic weight, with a density variously predicted to be either 22 g/cm3 or 14 g/cm3.[3] Flerovium is expected to crystallize in the face-centred cubic crystal structure like that of its lighter congener lead,[10] although earlier calculations predicted a hexagonal close-packed crystal structure due to spin-orbit coupling effects.[92] The electron of the hydrogen-like flerovium ion (oxidized so that it only has one electron, Fl113+) is expected to move so fast that it has a mass 1.79 times that of a stationary electron, due to relativistic effects. For comparison, the figures for hydrogen-like lead and tin are expected to be 1.25 and 1.073 respectively.[93] Flerovium would form weaker metal–metal bonds than lead and would be adsorbed less on surfaces.[93]

Chemical[edit]

Flerovium is the heaviest known member of group 14 in the periodic table, below lead, and is projected to be the second member of the 7p series of chemical elements. Nihonium and flerovium are expected to form a very short subperiod, coming between the filling of the 6d5/2 and 7p1/2 subshells. Their chemical behaviour is expected to be very distinctive: nihonium's homology to thallium has been called "doubtful" by computational chemists, while flerovium's to lead has been called only "formal".[94]

The first five members of group 14 show the group oxidation state of +4 and the latter members have an increasingly prominent +2 chemistry due to the onset of the inert pair effect. Tin represents the point at which the stability of the +2 and +4 states are similar, and lead(II) is the most stable of all the chemically well-understood group 14 elements in the +2 oxidation state.[3] The 7s orbitals are very highly stabilized in flerovium and thus a very large sp3 orbital hybridization is required to achieve the +4 oxidation state, so flerovium is expected to be even more stable than lead in its strongly predominant +2 oxidation state and its +4 oxidation state should be highly unstable.[3] For example, flerovium dioxide (FlO2) is expected to be highly unstable to decomposition into its constituent elements (and would not be formed from the direct reaction of flerovium with oxygen),[3][95] and flerovane (FlH4), which should have Fl–H bond lengths of 1.787 Å,[7] is predicted to be more thermodynamically unstable than plumbane, spontaneously decomposing into flerovium(II) hydride (FlH2) and hydrogen gas.[96] Flerovium tetrafluoride (FlF4)[97] would have bonding mostly due to sd hybridizations rather than sp3 hybridizations,[98] and its decomposition to the difluoride and fluorine gas would be exothermic.[7] The gross destabilization of all the tetrahalides (for example, FlCl4 is destabilized by about 400 kJ/mol) is unfortunate because otherwise these compounds would be very useful in gas-phase chemical studies of flerovium.[7] The corresponding polyfluoride anion FlF2−

6 should be unstable to hydrolysis in aqueous solution, and flerovium(II) polyhalide anions such as FlBr−

3 and FlI−

3 are predicted to form preferentially in flerovium-containing solutions.[3] The sd hybridizations were suggested in early calculations as the 7s and 6d electrons in flerovium share approximately the same energy, which would allow a volatile hexafluoride to form, but later calculations do not confirm this possibility.[6] In general, the spin-orbit contraction of the 7p1/2 orbital should lead to smaller bond lengths and larger bond angles: this has been theoretically confirmed in FlH2.[7] Nevertheless, even FlH2 should be relativistically destabilized by 2.6 eV to below Fl+H2; the large spin–orbit effects also break down the usual singlet–triplet divide in the group 14 dihydrides. FlF2 and FlCl2 are predicted to be more stable than FlH2.[99]

Due to the relativistic stabilization of flerovium's 7s27p2

1/2 valence electron configuration, the 0 oxidation state should also be more stable for flerovium than for lead, as the 7p1/2 electrons begin to also exhibit a mild inert pair effect:[3] this stabilization of the neutral state may bring about some similarities between the behaviour of flerovium and the noble gas radon.[19] Due to the expected relative inertness of flerovium, its diatomic compounds FlH and FlF should have lower energies of dissociation than the corresponding lead compounds PbH and PbF.[7] Flerovium(IV) should be even more electronegative than lead(IV);[97] lead(IV) has electronegativity 2.33 on the Pauling scale, though the lead(II) value is only 1.87. Flerovium is expected to be a very noble metal: the predicted standard electrode potential of +0.9 V for the Fl2+/Fl couple is comparable to the +0.915 V for the Pd2+/Pd couple of palladium.[3]

Flerovium(II) should be more stable than lead(II), and polyhalide ions and compounds of types FlX+, FlX2, FlX−

3, and FlX2−

4 (X = Cl, Br, I) are expected to form readily. The fluorides would undergo strong hydrolysis in aqueous solution.[3] All the flerovium dihalides are expected to be stable,[3] with the difluoride being water-soluble.[100] Spin-orbit effects would destabilize flerovium dihydride (FlH2) by almost 2.6 eV (250 kJ/mol).[95] In solution, flerovium would also form the oxyanion flerovite (FlO2−

2) in aqueous solution, analogous to plumbite. Flerovium(II) sulfate (FlSO4) and sulfide (FlS) should be very insoluble in water, and flerovium(II) acetate (FlC2H3O2) and nitrate (Fl(NO3)2) should be quite water-soluble.[6] The standard electrode potential for the reduction of Fl2+ ions to metallic flerovium is estimated to be around +0.9 V, confirming the increased stability of flerovium in the neutral state.[3] In general, due to the relativistic stabilization of the 7p1/2 spinor, Fl2+ is expected to have properties intermediate between those of Hg2+ or Cd2+ and its lighter congener Pb2+.[3]

Experimental chemistry[edit]

Flerovium is currently the heaviest element to have had its chemistry experimentally investigated, although the chemical investigations have so far not led to a conclusive result. Two experiments were performed in April–May 2007 in a joint FLNR-PSI collaboration aiming to study the chemistry of copernicium. The first experiment involved the reaction 242Pu(48Ca,3n)287Fl and the second the reaction 244Pu(48Ca,4n)288Fl: these reactions produce short-lived flerovium isotopes whose copernicium daughters would then be studied.[101] The adsorption properties of the resultant atoms on a gold surface were compared with those of radon, as it was then expected that copernicium's full-shell electron configuration would lead to noble-gas like behaviour.[101] Noble gases interact with metal surfaces very weakly, which is uncharacteristic of metals.[101]

The first experiment allowed detection of three atoms of 283Cn but also seemingly detected 1 atom of 287Fl. This result was a surprise given the transport time of the product atoms is ~2 s, so the flerovium atoms produced should have decayed to copernicium before adsorption. In the second reaction, 2 atoms of 288Fl and possibly 1 atom of 289Fl were detected. Two of the three atoms displayed adsorption characteristics associated with a volatile, noble-gas-like element, which has been suggested but is not predicted by more recent calculations. These experiments provided independent confirmation for the discovery of copernicium, flerovium, and livermorium via comparison with published decay data. Further experiments in 2008 to confirm this important result detected a single atom of 289Fl, and supported previous data showing flerovium having a noble-gas-like interaction with gold.[101]

The experimental support for a noble-gas-like flerovium soon weakened. In 2009 and 2010, the FLNR-PSI collaboration synthesized further atoms of flerovium to follow up their 2007 and 2008 studies. In particular, the first three flerovium atoms synthesized in the 2010 study suggested again a noble-gas-like character, but the complete set taken together resulted in a more ambiguous interpretation, unusual for a metal in the carbon group but not fully like a noble gas in character.[102] In their paper, the scientists refrained from calling flerovium's chemical properties "close to those of noble gases", as had previously been done in the 2008 study.[102] Flerovium's volatility was again measured through interactions with a gold surface, and provided indications that the volatility of flerovium was comparable to that of mercury, astatine, and the simultaneously investigated copernicium, which had been shown in the study to be a very volatile noble metal, conforming to its being the heaviest group 12 element known.[102] Nevertheless, it was pointed out that this volatile behaviour was not expected for a usual group 14 metal.[102]

In even later experiments from 2012 at the GSI, the chemical properties of flerovium were found to be more metallic than noble-gas-like. Jens Volker Kratz and Christoph Düllmann specifically named copernicium and flerovium as belonging to a new category of "volatile metals"; Kratz even speculated that they might be gaseous at standard temperature and pressure.[54][103] These "volatile metals", as a category, were expected to fall between normal metals and noble gases in terms of adsorption properties.[54] Contrary to the 2009 and 2010 results, it was shown in the 2012 experiments that the interactions of flerovium and copernicium respectively with gold were about equal.[104] Further studies showed that flerovium was more reactive than copernicium, in contradiction to previous experiments and predictions.[54]

In a 2014 paper detailing the experimental results of the chemical characterisation of flerovium, the GSI group wrote: "[flerovium] is the least reactive element in the group, but still a metal."[105] Nevertheless, in a 2016 conference about the chemistry and physics of heavy and superheavy elements, Alexander Yakushev and Robert Eichler, two scientists who had been active at GSI and FLNR in determining the chemistry of flerovium, still urged caution based on the inconsistencies of the various experiments previously listed, noting that the question of whether flerovium was a metal or a noble gas was still open with the available evidence: one study suggested a weak noble-gas-like interaction between flerovium and gold, while the other suggested a stronger metallic interaction. The same year, new experiments aimed at probing the chemistry of copernicium and flerovium were conducted at GSI's TASCA facility, and the data from these experiments is currently being analysed. As such, unambiguous determination of the chemical characteristics of flerovium has yet to have been established,[106] although the experiments to date have allowed the first experimental estimation of flerovium's boiling point: around −60 °C, so that it is probably a gas at standard conditions.[4] The longer-lived flerovium isotope 289Fl has been considered of interest for future radiochemical studies.[107]

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ In nuclear physics, an element is called heavy if its atomic number is high; lead (element 82) is one example of such a heavy element. The term "superheavy elements" typically refers to elements with atomic number greater than 103 (although there are other definitions, such as atomic number greater than 100[20] or 112;[21] sometimes, the term is presented an equivalent to the term "transactinide", which puts an upper limit before the beginning of the hypothetical superactinide series).[22] Terms "heavy isotopes" (of a given element) and "heavy nuclei" mean what could be understood in the common language—isotopes of high mass (for the given element) and nuclei of high mass, respectively.

- ^ In 2009, a team at JINR led by Oganessian published results of their attempt to create hassium in a symmetric 136Xe + 136Xe reaction. They failed to observe a single atom in such a reaction, putting the upper limit on the cross section, the measure of probability of a nuclear reaction, as 2.5 pb.[23] In comparison, the reaction that resulted in hassium discovery, 208Pb + 58Fe, had a cross section of ~20 pb (more specifically, 19+19

−11 pb), as estimated by the discoverers.[24] - ^ The greater the excitation energy, the more neutrons are ejected. If the excitation energy is lower than energy binding each neutron to the rest of the nucleus, neutrons are not emitted; instead, the compound nucleus de-excites by emitting a gamma ray.[28]

- ^ The definition by the IUPAC/IUPAP Joint Working Party states that a chemical element can only be recognized as discovered if a nucleus of it has not decayed within 10−14 seconds. This value was chosen as an estimate of how long it takes a nucleus to acquire its outer electrons and thus display its chemical properties.[29] This figure also marks the generally accepted upper limit for lifetime of a compound nucleus.[30]

- ^ This separation is based on that the resulting nuclei move past the target more slowly then the unreacted beam nuclei. The separator contains electric and magnetic fields whose effects on a moving particle cancel out for a specific velocity of a particle.[32] Such separation can also be aided by a time-of-flight measurement and a recoil energy measurement; a combination of the two may allow to estimate the mass of a nucleus.[33]

- ^ Not all decay modes are caused by electrostatic repulsion. For example, beta decay is caused by the weak interaction.[38]

- ^ Since mass of a nucleus is not measured directly but is rather calculated from that of another nucleus, such measurement is called indirect. Direct measurements are also possible, but for the most part they have remained unavailable for superheavy nuclei.[39] The first direct measurement of mass of a superheavy nucleus was reported in 2018 at LBNL.[40] Mass was determined from the location of a nucleus after the transfer (the location helps determine its trajectory, which is linked to the mass-to-charge ratio of the nucleus, since the transfer was done in presence of a magnet).[41]

- ^ Spontaneous fission was discovered by Soviet physicist Georgy Flerov,[42] a leading scientist at JINR, and thus it was a "hobbyhorse" for the facility.[43] In contrast, the LBL scientists believed fission information was not sufficient for a claim of synthesis of an element. They believed spontaneous fission had not been studied enough to use it for identification of a new element, since there was a difficulty of establishing that a compound nucleus had only ejected neutrons and not charged particles like protons or alpha particles.[30] They thus preferred to link new isotopes to the already known ones by successive alpha decays.[42]

- ^ For instance, element 102 was mistakenly identified in 1957 at the Nobel Institute of Physics in Stockholm, Stockholm County, Sweden.[44] There were no earlier definitive claims of creation of this element, and the element was assigned a name by its Swedish, American, and British discoverers, nobelium. It was later shown that the identification was incorrect.[45] The following year, RL was unable to reproduce the Swedish results and announced instead their synthesis of the element; that claim was also disproved later.[45] JINR insisted that they were the first to create the element and suggested a name of their own for the new element, joliotium;[46] the Soviet name was also not accepted (JINR later referred to the naming of element 102 as "hasty").[47] The name "nobelium" remained unchanged on account of its widespread usage.[48]

- ^ Different sources give different values for half-lives; the most recently published values are listed.

- ^ This isotope is unconfirmed

- ^ This isotope is unconfirmed

- ^ Specifically, 291Mc, 291Fl, 291Nh, 287Nh, 287Cn, 287Rg, 283Rg, and 283Ds, which are expected to decay to the relatively longer-lived nuclei 283Mt, 287Ds, and 291Cn.[71]

- ^ It is estimated that it requires around 10−14 s for the nucleons to arrange themselves into nuclear shells, at which point the compound nucleus becomes a nuclide, and this number is used by IUPAC as the minimum half-life a claimed isotope must have to be recognized as a nuclide.[82]

- ^ The quantum number corresponds to the letter in the electron orbital name: 0 to s, 1 to p, 2 to d, etc. See azimuthal quantum number for more information.

References[edit]

- ^ "Flerovium and Livermorium". Periodic Table of Videos. The University of Nottingham. Retrieved 4 June 2012.

- ^ a b Gong, Sheng; Wu, Wei; Wang, Fancy Qian; Liu, Jie; Zhao, Yu; Shen, Yiheng; Wang, Shuo; Sun, Qiang; Wang, Qian (8 February 2019). "Classifying superheavy elements by machine learning". Physical Review A. 99: 022110-1–7. doi:10.1103/PhysRevA.99.022110.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v Hoffman, Darleane C.; Lee, Diana M.; Pershina, Valeria (2006). "Transactinides and the future elements". In Morss; Edelstein, Norman M.; Fuger, Jean (eds.). The Chemistry of the Actinide and Transactinide Elements (3rd ed.). Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer Science+Business Media. ISBN 978-1-4020-3555-5.

- ^ a b c Oganessian, Yu. Ts. (27 January 2017). "Discovering Superheavy Elements". Oak Ridge National Laboratory. Retrieved 21 April 2017.

- ^ Seaborg, G. T. "Transuranium element". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 16 March 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Fricke, Burkhard (1975). "Superheavy elements: a prediction of their chemical and physical properties". Recent Impact of Physics on Inorganic Chemistry. Structure and Bonding. 21: 89–144. doi:10.1007/BFb0116498. ISBN 978-3-540-07109-9. Retrieved 4 October 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f Schwerdtfeger, Peter; Seth, Michael (2002). "Relativistic Quantum Chemistry of the Superheavy Elements. Closed-Shell Element 114 as a Case Study" (PDF). Journal of Nuclear and Radiochemical Sciences. 3 (1): 133–136. doi:10.14494/jnrs2000.3.133. Retrieved 12 September 2014.

- ^ Pershina, Valeria. "Theoretical Chemistry of the Heaviest Elements". In Schädel, Matthias; Shaughnessy, Dawn (eds.). The Chemistry of Superheavy Elements (2nd ed.). Springer Science & Business Media. p. 154. ISBN 9783642374661.

- ^ Bonchev, Danail; Kamenska, Verginia (1981). "Predicting the Properties of the 113–120 Transactinide Elements". Journal of Physical Chemistry. American Chemical Society. 85 (9): 1177–1186. doi:10.1021/j150609a021.

- ^ a b Maiz Hadj Ahmed, H.; Zaoui, A.; Ferhat, M. (2017). "Revisiting the ground state phase stability of super-heavy element Flerovium". Cogent Physics. 4 (1). doi:10.1080/23311940.2017.1380454. Retrieved 26 November 2018.

- ^ a b "Element 114 is Named Flerovium and Element 116 is Named Livermorium" (Press release). IUPAC. 30 May 2012.

- ^ Utyonkov, V.K. et al. (2015) Synthesis of superheavy nuclei at limits of stability: 239,240Pu + 48Ca and 249–251Cf + 48Ca reactions. Super Heavy Nuclei International Symposium, Texas A & M University, College Station TX, USA, March 31 – April 02, 2015

- ^ a b c Utyonkov, V. K.; Brewer, N. T.; Oganessian, Yu. Ts.; Rykaczewski, K. P.; Abdullin, F. Sh.; Dmitriev, S. N.; Grzywacz, R. K.; Itkis, M. G.; Miernik, K.; Polyakov, A. N.; Roberto, J. B.; Sagaidak, R. N.; Shirokovsky, I. V.; Shumeiko, M. V.; Tsyganov, Yu. S.; Voinov, A. A.; Subbotin, V. G.; Sukhov, A. M.; Sabel'nikov, A. V.; Vostokin, G. K.; Hamilton, J. H.; Stoyer, M. A.; Strauss, S. Y. (15 September 2015). "Experiments on the synthesis of superheavy nuclei 284Fl and 285Fl in the 239,240Pu + 48Ca reactions". Physical Review C. 92 (3): 034609-1–034609-10. Bibcode:2015PhRvC..92c4609U. doi:10.1103/PhysRevC.92.034609.

- ^ a b c Utyonkov, V. K.; Brewer, N. T.; Oganessian, Yu. Ts.; Rykaczewski, K. P.; Abdullin, F. Sh.; Dimitriev, S. N.; Grzywacz, R. K.; Itkis, M. G.; Miernik, K.; Polyakov, A. N.; Roberto, J. B.; Sagaidak, R. N.; Shirokovsky, I. V.; Shumeiko, M. V.; Tsyganov, Yu. S.; Voinov, A. A.; Subbotin, V. G.; Sukhov, A. M.; Karpov, A. V.; Popeko, A. G.; Sabel'nikov, A. V.; Svirikhin, A. I.; Vostokin, G. K.; Hamilton, J. H.; Kovrinzhykh, N. D.; Schlattauer, L.; Stoyer, M. A.; Gan, Z.; Huang, W. X.; Ma, L. (30 January 2018). "Neutron-deficient superheavy nuclei obtained in the 240Pu+48Ca reaction". Physical Review C. 97 (1): 014320–1—014320–10. Bibcode:2018PhRvC..97a4320U. doi:10.1103/PhysRevC.97.014320.

- ^ a b Hofmann, S.; Heinz, S.; Mann, R.; Maurer, J.; Münzenberg, G.; Antalic, S.; Barth, W.; Burkhard, H. G.; Dahl, L.; Eberhardt, K.; Grzywacz, R.; Hamilton, J. H.; Henderson, R. A.; Kenneally, J. M.; Kindler, B.; Kojouharov, I.; Lang, R.; Lommel, B.; Miernik, K.; Miller, D.; Moody, K. J.; Morita, K.; Nishio, K.; Popeko, A. G.; Roberto, J. B.; Runke, J.; Rykaczewski, K. P.; Saro, S.; Schneidenberger, C.; Schött, H. J.; Shaughnessy, D. A.; Stoyer, M. A.; Thörle-Pospiech, P.; Tinschert, K.; Trautmann, N.; Uusitalo, J.; Yeremin, A. V. (2016). "Remarks on the Fission Barriers of SHN and Search for Element 120". In Peninozhkevich, Yu. E.; Sobolev, Yu. G. (eds.). Exotic Nuclei: EXON-2016 Proceedings of the International Symposium on Exotic Nuclei. Exotic Nuclei. pp. 155–164. ISBN 9789813226555.

- ^ a b c d e Hofmann, S.; Heinz, S.; Mann, R.; Maurer, J.; Münzenberg, G.; Antalic, S.; Barth, W.; Burkhard, H. G.; Dahl, L.; Eberhardt, K.; Grzywacz, R.; Hamilton, J. H.; Henderson, R. A.; Kenneally, J. M.; Kindler, B.; Kojouharov, I.; Lang, R.; Lommel, B.; Miernik, K.; Miller, D.; Moody, K. J.; Morita, K.; Nishio, K.; Popeko, A. G.; Roberto, J. B.; Runke, J.; Rykaczewski, K. P.; Saro, S.; Scheidenberger, C.; Schött, H. J.; Shaughnessy, D. A.; Stoyer, M. A.; Thörle-Popiesch, P.; Tinschert, K.; Trautmann, N.; Uusitalo, J.; Yeremin, A. V. (2016). "Review of even element super-heavy nuclei and search for element 120". The European Physics Journal A. 2016 (52): 180. Bibcode:2016EPJA...52..180H. doi:10.1140/epja/i2016-16180-4.

- ^ a b c Kaji, Daiya; Morita, Kosuke; Morimoto, Kouji; Haba, Hiromitsu; Asai, Masato; Fujita, Kunihiro; Gan, Zaiguo; Geissel, Hans; Hasebe, Hiroo; Hofmann, Sigurd; Huang, MingHui; Komori, Yukiko; Ma, Long; Maurer, Joachim; Murakami, Masashi; Takeyama, Mirei; Tokanai, Fuyuki; Tanaka, Taiki; Wakabayashi, Yasuo; Yamaguchi, Takayuki; Yamaki, Sayaka; Yoshida, Atsushi (2017). "Study of the Reaction 48Ca + 248Cm → 296Lv* at RIKEN-GARIS". Journal of the Physical Society of Japan. 86 (3): 034201–1–7. Bibcode:2017JPSJ...86c4201K. doi:10.7566/JPSJ.86.034201.

- ^ Eichler, Robert; et al. (2010). "Indication for a volatile element 114" (PDF). Radiochimica Acta. 98 (3): 133–139. doi:10.1524/ract.2010.1705.

- ^ a b Gäggeler, H. W. (5–7 November 2007). "Gas Phase Chemistry of Superheavy Elements" (PDF). Paul Scherrer Institute. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 February 2012. Retrieved 10 August 2013.

- ^ Krämer, K. (2016). "Explainer: superheavy elements". Chemistry World. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

- ^ "Discovery of Elements 113 and 115". Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory. Archived from the original on 11 September 2015. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

- ^ Eliav, E.; Kaldor, U.; Borschevsky, A. (2018). Scott, R. A. (ed.). Electronic Structure of the Transactinide Atoms. Encyclopedia of Inorganic and Bioinorganic Chemistry. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 1–16. doi:10.1002/9781119951438.eibc2632. ISBN 978-1-119-95143-8.

- ^ Oganessian, Yu. Ts.; Dmitriev, S. N.; Yeremin, A. V.; et al. (2009). "Attempt to produce the isotopes of element 108 in the fusion reaction 136Xe + 136Xe". Physical Review C. 79 (2): 024608. doi:10.1103/PhysRevC.79.024608. ISSN 0556-2813.

- ^ Münzenberg, G.; Armbruster, P.; Folger, H.; et al. (1984). "The identification of element 108" (PDF). Zeitschrift für Physik A. 317 (2): 235–236. Bibcode:1984ZPhyA.317..235M. doi:10.1007/BF01421260. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 June 2015. Retrieved 20 October 2012.

- ^ a b Subramanian, S. "Making New Elements Doesn't Pay. Just Ask This Berkeley Scientist". Bloomberg Businessweek. Retrieved 18 January 2020.

- ^ a b Ivanov, D. (2019). "Сверхтяжелые шаги в неизвестное" [Superheavy steps into the unknown]. nplus1.ru (in Russian). Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- ^ Hinde, D. (2017). "Something new and superheavy at the periodic table". The Conversation. Retrieved 30 January 2020.

- ^ a b Krása, A. (2010). "Neutron Sources for ADS" (PDF). Faculty of Nuclear Sciences and Physical Engineering. Czech Technical University in Prague. pp. 4–8. Retrieved 20 October 2019.

- ^ Wapstra, A. H. (1991). "Criteria that must be satisfied for the discovery of a new chemical element to be recognized" (PDF). Pure and Applied Chemistry. 63 (6): 883. doi:10.1351/pac199163060879. ISSN 1365-3075.

- ^ a b Hyde, E. K.; Hoffman, D. C.; Keller, O. L. (1987). "A History and Analysis of the Discovery of Elements 104 and 105". Radiochimica Acta. 42 (2): 67–68. doi:10.1524/ract.1987.42.2.57. ISSN 2193-3405.

- ^ a b c Chemistry World (2016). "How to Make Superheavy Elements and Finish the Periodic Table [Video]". Scientific American. Retrieved 27 January 2020.

- ^ Hoffman 2000, p. 334.

- ^ Hoffman 2000, p. 335.

- ^ Zagrebaev 2013, p. 3.

- ^ Beiser 2003, p. 432.

- ^ Staszczak, A.; Baran, A.; Nazarewicz, W. (2013). "Spontaneous fission modes and lifetimes of superheavy elements in the nuclear density functional theory". Physical Review C. 87 (2): 024320–1. arXiv:1208.1215. Bibcode:2013PhRvC..87b4320S. doi:10.1103/physrevc.87.024320. ISSN 0556-2813.

- ^ Audi 2017, pp. 030001-129–030001-138.

- ^ Beiser 2003, p. 439.

- ^ Oganessian, Yu. Ts.; Rykaczewski, K. P. (2015). "A beachhead on the island of stability". Physics Today. 68 (8): 32–38. Bibcode:2015PhT....68h..32O. doi:10.1063/PT.3.2880. ISSN 0031-9228. OSTI 1337838.

- ^ Grant, A. (2018). "Weighing the heaviest elements". Physics Today. doi:10.1063/PT.6.1.20181113a.

- ^ Howes, L. (2019). "Exploring the superheavy elements at the end of the periodic table". Chemical & Engineering News. Retrieved 27 January 2020.

- ^ a b Robinson, A. E. (2019). "The Transfermium Wars: Scientific Brawling and Name-Calling during the Cold War". Distillations. Retrieved 22 February 2020.

- ^ "Популярная библиотека химических элементов. Сиборгий (экавольфрам)" [Popular library of chemical elements. Seaborgium (eka-tungsten)]. n-t.ru (in Russian). Retrieved 7 January 2020. Reprinted from "Экавольфрам" [Eka-tungsten]. Популярная библиотека химических элементов. Серебро — Нильсборий и далее [Popular library of chemical elements. Silver through nielsbohrium and beyond] (in Russian). Nauka. 1977.

- ^ "Nobelium - Element information, properties and uses | Periodic Table". Royal Society of Chemistry. Retrieved 1 March 2020.

- ^ a b Kragh 2018, pp. 38–39.

- ^ Kragh 2018, p. 40.

- ^ Ghiorso, A.; Seaborg, G. T.; Oganessian, Yu. Ts.; et al. (1993). "Responses on the report 'Discovery of the Transfermium elements' followed by reply to the responses by Transfermium Working Group" (PDF). Pure and Applied Chemistry. 65 (8): 1815–1824. doi:10.1351/pac199365081815. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 November 2013. Retrieved 7 September 2016.

- ^ Commission on Nomenclature of Inorganic Chemistry (1997). "Names and symbols of transfermium elements (IUPAC Recommendations 1997)" (PDF). Pure and Applied Chemistry. 69 (12): 2471–2474. doi:10.1351/pac199769122471.

- ^ a b c d e Sacks, O. (8 February 2004). "Greetings From the Island of Stability". The New York Times.

- ^ Bemis, C.E.; Nix, J.R. (1977). "Superheavy elements - the quest in perspective" (PDF). Comments on Nuclear and Particle Physics. 7 (3): 65–78. ISSN 0010-2709.

- ^ Emsley, John (2011). Nature's Building Blocks: An A-Z Guide to the Elements (New ed.). New York, NY: Oxford University Press. p. 580. ISBN 978-0-19-960563-7.

- ^ Hoffman, D.C; Ghiorso, A.; Seaborg, G.T. (2000). The Transuranium People: The Inside Story. Imperial College Press. Bibcode:2000tpis.book.....H. ISBN 978-1-86094-087-3.

- ^ Epherre, M.; Stephan, C. (1975). "Les éléments superlourds" (PDF). Le Journal de Physique Colloques (in French). 11 (36): C5–159–164. doi:10.1051/jphyscol:1975541.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Kratz, J. V. (5 September 2011). The Impact of Superheavy Elements on the Chemical and Physical Sciences (PDF). 4th International Conference on the Chemistry and Physics of the Transactinide Elements. Retrieved 27 August 2013.

- ^ Chapman, Kit (30 November 2016). "What it takes to make a new element". Chemistry World. Royal Society of Chemistry. Retrieved 3 December 2016.

- ^ a b Oganessian, Yu. Ts.; et al. (1999). "Synthesis of Superheavy Nuclei in the 48Ca + 244Pu Reaction" (PDF). Physical Review Letters. 83 (16): 3154. Bibcode:1999PhRvL..83.3154O. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.83.3154.

- ^ a b Oganessian, Yu. Ts.; et al. (2000). "Synthesis of superheavy nuclei in the 48Ca + 244Pu reaction: 288114" (PDF). Physical Review C. 62 (4): 041604. Bibcode:2000PhRvC..62d1604O. doi:10.1103/PhysRevC.62.041604.

- ^ Oganessian, Yu. Ts.; et al. (2004). "Measurements of cross sections and decay properties of the isotopes of elements 112, 114, and 116 produced in the fusion reactions 233,238U, 242Pu, and 248Cm + 48Ca" (PDF). Physical Review C. 70 (6): 064609. Bibcode:2004PhRvC..70f4609O. doi:10.1103/PhysRevC.70.064609. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 May 2008.

- ^ a b c Browne, M. W. (27 February 1999). "Glenn Seaborg, Leader of Team That Found Plutonium, Dies at 86". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 22 May 2013. Retrieved 26 August 2013.

- ^ a b Audi, G.; Kondev, F. G.; Wang, M.; Huang, W. J.; Naimi, S. (2017). "The NUBASE2016 evaluation of nuclear properties" (PDF). Chinese Physics C. 41 (3): 030001. Bibcode:2017ChPhC..41c0001A. doi:10.1088/1674-1137/41/3/030001.

- ^ Thoennessen, M. (2016). The Discovery of Isotopes: A Complete Compilation. Springer. pp. 229, 234, 238. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-31763-2. ISBN 978-3-319-31761-8. LCCN 2016935977.

- ^ a b c d Oganessian, Y.T. (2015). "Super-heavy element research". Reports on Progress in Physics. 78 (3): 036301. Bibcode:2015RPPh...78c6301O. doi:10.1088/0034-4885/78/3/036301. PMID 25746203.

- ^ Oganessian, Yu. Ts.; et al. (1999). "Synthesis of nuclei of the superheavy element 114 in reactions induced by 48Ca". Nature. 400 (6741): 242. Bibcode:1999Natur.400..242O. doi:10.1038/22281.

- ^ a b Oganessian, Yu. Ts.; et al. (2004). "Measurements of cross sections for the fusion-evaporation reactions 244Pu(48Ca,xn)292−x114 and 245Cm(48Ca,xn)293−x116". Physical Review C. 69 (5): 054607. Bibcode:2004PhRvC..69e4607O. doi:10.1103/PhysRevC.69.054607.

- ^ Barber, R. C.; Gäggeler, H. W.; Karol, P. J.; Nakahara, H.; Vardaci, E.; Vogt, E. (2009). "Discovery of the element with atomic number 112 (IUPAC Technical Report)" (PDF). Pure and Applied Chemistry. 81 (7): 1331. doi:10.1351/PAC-REP-08-03-05.

- ^ Barber, R. C.; Karol, P. J.; Nakahara, H.; Vardaci, E.; Vogt, E. W. (2011). "Discovery of the elements with atomic numbers greater than or equal to 113 (IUPAC Technical Report)". Pure and Applied Chemistry. 83 (7): 1485. doi:10.1351/PAC-REP-10-05-01.

- ^ Forsberg, U.; Rudolph, D.; Fahlander, C.; Golubev, P.; Sarmiento, L. G.; Åberg, S.; Block, M.; Düllmann, Ch. E.; Heßberger, F. P.; Kratz, J. V.; Yakushev, Alexander (9 July 2016). "A new assessment of the alleged link between element 115 and element 117 decay chains" (PDF). Physics Letters B. 760 (2016): 293–6. Bibcode:2016PhLB..760..293F. doi:10.1016/j.physletb.2016.07.008. Retrieved 2 April 2016.

- ^ Forsberg, Ulrika; Fahlander, Claes; Rudolph, Dirk (2016). Congruence of decay chains of elements 113, 115, and 117 (PDF). Nobel Symposium NS160 – Chemistry and Physics of Heavy and Superheavy Elements. doi:10.1051/epjconf/201613102003.

- ^ Morita, Kōsuke (2014). "Research on Superheavy Elements at RIKEN" (PDF). APS Division of Nuclear Physics Meeting Abstracts. 2014: DG.002. Bibcode:2014APS..DNP.DG002M. Retrieved 28 April 2017.

- ^ Morimoto, Kouji (October 2009). "Production and Decay Properties of 266Bh and its daughter nuclei by using the 248Cm(23Na,5n)266Bh Reaction" (PDF). www.kernchemie.uni-mainz.de. University of Mainz. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 September 2017. Retrieved 28 April 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Zagrebaev, Valeriy; Karpov, Alexander; Greiner, Walter (2013). "Future of superheavy element research: Which nuclei could be synthesized within the next few years?" (PDF). Journal of Physics: Conference Series. 420. IOP Science. pp. 1–15. Retrieved 20 August 2013.

- ^ Heinz, Sophie (1 April 2015). "Probing the Stability of Superheavy Nuclei with Radioactive Ion Beams" (PDF). cyclotron.tamu.edu. Texas A & M University. Retrieved 30 April 2017.

- ^ Chatt, J. (1979). "Recommendations for the naming of elements of atomic numbers greater than 100". Pure and Applied Chemistry. 51 (2): 381–384. doi:10.1351/pac197951020381.

- ^ Koppenol, W. H. (2002). "Naming of new elements (IUPAC Recommendations 2002)" (PDF). Pure and Applied Chemistry. 74 (5): 787. doi:10.1351/pac200274050787.

- ^ Brown, M. (6 June 2011). "Two Ultraheavy Elements Added to Periodic Table". Wired. Retrieved 7 June 2011.

- ^ a b Welsh, J. (2 December 2011). "Two Elements Named: Livermorium and Flerovium". LiveScience. Retrieved 2 December 2011.

- ^ "Российские физики предложат назвать 116 химический элемент московием" [Russian physicists have offered to call 116 chemical element moscovium]. RIA Novosti. 26 March 2011. Retrieved 8 May 2011. Mikhail Itkis, the vice-director of JINR stated: "We would like to name element 114 after Georgy Flerov – flerovium, and the second [element 116] – moscovium, not after Moscow, but after Moscow Oblast".

- ^ Popeko, Andrey G. (2016). "Synthesis of superheavy elements" (PDF). jinr.ru. Joint Institute for Nuclear Research. Retrieved 4 February 2018.

- ^ Oganessian, Yu. Ts. (10 October 2015). "Гамбургский счет" [Hamburg reckoning] (Interview) (in Russian). Interviewed by Orlova, O. Public Television of Russia. Retrieved 18 January 2020.

- ^ Kalinkin, B. N.; Gareev, F. A. (2001). Synthesis of Superheavy elements and Theory of Atomic Nucleus. Exotic Nuclei. p. 118. arXiv:nucl-th/0111083v2. Bibcode:2002exnu.conf..118K. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.264.7426. doi:10.1142/9789812777300_0009. ISBN 978-981-238-025-8.

- ^ a b "JINR Annual Reports 2000–2006". JINR. Retrieved 27 August 2013.

- ^ a b Emsley, John (2011). Nature's Building Blocks: An A-Z Guide to the Elements (New ed.). New York, NY: Oxford University Press. p. 590. ISBN 978-0-19-960563-7.

- ^ a b c Zagrebaev, V.; Greiner, W. (2008). "Synthesis of superheavy nuclei: A search for new production reactions". Physical Review C. 78 (3): 034610. arXiv:0807.2537. Bibcode:2008PhRvC..78c4610Z. doi:10.1103/PhysRevC.78.034610.

- ^ Chowdhury, P. R.; Samanta, C.; Basu, D. N. (2006). "α decay half-lives of new superheavy elements". Physical Review C. 73 (1): 014612. arXiv:nucl-th/0507054. Bibcode:2006PhRvC..73a4612C. doi:10.1103/PhysRevC.73.014612.

- ^ Samanta, C.; Chowdhury, P. R.; Basu, D. N. (2007). "Predictions of alpha decay half lives of heavy and superheavy elements". Nuclear Physics A. 789 (1–4): 142–154. arXiv:nucl-th/0703086. Bibcode:2007NuPhA.789..142S. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.264.8177. doi:10.1016/j.nuclphysa.2007.04.001.

- ^ Chowdhury, P. R.; Samanta, C.; Basu, D. N. (2008). "Search for long lived heaviest nuclei beyond the valley of stability". Physical Review C. 77 (4): 044603. arXiv:0802.3837. Bibcode:2008PhRvC..77d4603C. doi:10.1103/PhysRevC.77.044603.

- ^ Roy Chowdhury, P.; Samanta, C.; Basu, D. N. (2008). "Nuclear half-lives for α-radioactivity of elements with 100 ≤ Z ≤ 130". Atomic Data and Nuclear Data Tables. 94 (6): 781–806. arXiv:0802.4161. Bibcode:2008ADNDT..94..781C. doi:10.1016/j.adt.2008.01.003.

- ^ Thayer 2010, pp. 63–64.

- ^ Faegri, K.; Saue, T. (2001). "Diatomic molecules between very heavy elements of group 13 and group 17: A study of relativistic effects on bonding". Journal of Chemical Physics. 115 (6): 2456. Bibcode:2001JChPh.115.2456F. doi:10.1063/1.1385366.

- ^ Thayer 2010, pp. 63–67.

- ^ Borschevsky, Anastasia; Pershina, Valeria; Kaldor, Uzi; Eliav, Ephraim. "Fully relativistic ab initio studies of superheavy elements" (PDF). www.kernchemie.uni-mainz.de. Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 January 2018. Retrieved 15 January 2018.

- ^ Hermann, Andreas; Furthmüller, Jürgen; Gäggeler, Heinz W.; Schwerdtfeger, Peter (2010). "Spin-orbit effects in structural and electronic properties for the solid state of the group-14 elements from carbon to superheavy element 114". Physical Review B. 82 (15): 155116–1–8. Bibcode:2010PhRvB..82o5116H. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.82.155116.

- ^ a b Thayer 2010, pp. 64.

- ^ Zaitsevskii, A.; van Wüllen, C.; Rusakov, A.; Titov, A. (September 2007). "Relativistic DFT and ab initio calculations on the seventh-row superheavy elements: E113 - E114" (PDF). jinr.ru. Retrieved 17 February 2018.

- ^ a b Pershina 2010, p. 502.

- ^ Pershina 2010, p. 503.

- ^ a b Thayer 2010, p. 83.

- ^ Fricke, B.; Greiner, W.; Waber, J. T. (1971). "The continuation of the periodic table up to Z = 172. The chemistry of superheavy elements" (PDF). Theoretica Chimica Acta. 21 (3): 235–260. doi:10.1007/BF01172015.

- ^ Balasubramanian, K. (30 July 2002). "Breakdown of the singlet and triplet nature of electronic states of the superheavy element 114 dihydride (114H2)". Journal of Chemical Physics. 117 (16): 7426–32. Bibcode:2002JChPh.117.7426B. doi:10.1063/1.1508371.

- ^ Winter, M. (2012). "Flerovium: The Essentials". WebElements. University of Sheffield. Retrieved 28 August 2008.

- ^ a b c d "Flerov Laboratory of Nuclear Reactions" (PDF). 2009. pp. 86–96. Retrieved 1 June 2012.

- ^ a b c d Eichler, Robert; Aksenov, N. V.; Albin, Yu. V.; Belozerov, A. V.; Bozhikov, G. A.; Chepigin, V. I.; Dmitriev, S. N.; Dressler, R.; Gäggeler, H. W.; Gorshkov, V. A.; Henderson, G. S. (2010). "Indication for a volatile element 114" (PDF). Radiochimica Acta. 98 (3): 133–139. doi:10.1524/ract.2010.1705.

- ^ Kratz, Jens Volker (2012). "The impact of the properties of the heaviest elements on the chemical and physical sciences". Radiochimica Acta. 100 (8–9): 569–578. doi:10.1524/ract.2012.1963.

- ^ Düllmann, Christoph E. (18 September 2012). Superheavy element 114 is a volatile metal. Archived from the original on 27 September 2013. Retrieved 25 September 2013.

- ^ Yakushev, Alexander; Gates, Jacklyn M.; Türler, Andreas; Schädel, Matthias; Düllmann, Christoph E.; Ackermann, Dieter; Andersson, Lise-Lotte; Block, Michael; Brüchle, Willy; Dvorak, Jan; Eberhardt, Klaus; Essel, Hans G.; Even, Julia; Forsberg, Ulrika; Gorshkov, Alexander; Graeger, Reimar; Gregorich, Kenneth E.; Hartmann, Willi; Herzberg, Rolf-Deitmar; Heßberger, Fritz P.; Hild, Daniel; Hübner, Annett; Jäger, Egon; Khuyagbaatar, Jadambaa; Kindler, Birgit; Kratz, Jens V.; Krier, Jörg; Kurz, Nikolaus; Lommel, Bettina; Niewisch, Lorenz J.; Nitsche, Heino; Omtvedt, Jon Petter; Parr, Edward; Qin, Zhi; Rudolph, Dirk; Runke, Jörg; Schausten, Birgitta; Schimpf, Erwin; Semchenkov, Andrey; Steiner, Jutta; Thörle-Pospiech, Petra; Uusitalo, Juha; Wegrzecki, Maciej; Wiehl, Norbert (2014). "Superheavy Element Flerovium (Element 114) Is a Volatile Metal" (PDF). Inorg. Chem. 53 (1624): 1624–1629. doi:10.1021/ic4026766. PMID 24456007. Retrieved 30 March 2017.

- ^ Yakushev, Alexander; Eichler, Robert (2016). Gas-phase chemistry of element 114, flerovium (PDF). Nobel Symposium NS160 – Chemistry and Physics of Heavy and Superheavy Elements. doi:10.1051/epjconf/201613107003.

- ^ Moody, Ken (30 November 2013). "Synthesis of Superheavy Elements". In Schädel, Matthias; Shaughnessy, Dawn (eds.). The Chemistry of Superheavy Elements (2nd ed.). Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 24–8. ISBN 9783642374661.

Bibliography[edit]

- Audi, G.; Kondev, F. G.; Wang, M.; et al. (2017). "The NUBASE2016 evaluation of nuclear properties". Chinese Physics C. 41 (3): 030001. Bibcode:2017ChPhC..41c0001A. doi:10.1088/1674-1137/41/3/030001.

- Beiser, A. (2003). Concepts of modern physics (6th ed.). McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-244848-1. OCLC 48965418.

- Hoffman, D. C.; Ghiorso, A.; Seaborg, G. T. (2000). The Transuranium People: The Inside Story. World Scientific. ISBN 978-1-78-326244-1.

- Kragh, H. (2018). From Transuranic to Superheavy Elements: A Story of Dispute and Creation. Springer. ISBN 978-3-319-75813-8.

- Zagrebaev, V.; Karpov, A.; Greiner, W. (2013). "Future of superheavy element research: Which nuclei could be synthesized within the next few years?". Journal of Physics: Conference Series. 420 (1): 012001. arXiv:1207.5700. Bibcode:2013JPhCS.420a2001Z. doi:10.1088/1742-6596/420/1/012001. ISSN 1742-6588.

Bibliography[edit]

- Barysz, M.; Ishikawa, Y., eds. (2010). Relativisic Methods for Chemists. Springer. ISBN 978-1-4020-9974-8.

- Thayer, J. S. (2010). "Relativistic Effects and the Chemistry of the Heavier Main Group Elements". Relativistic Methods for Chemists. Challenges and Advances in Computational Chemistry and Physics. 10. pp. 63–97. doi:10.1007/978-1-4020-9975-5_2. ISBN 978-1-4020-9974-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Stysziński, J. (2010). Why do we need relativistic computational methods?. p. 99.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pershina, V. (2010). Electronic structure and chemistry of the heaviest elements. p. 450.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links[edit]

- CERN Courier – First postcard from the island of nuclear stability

- CERN Courier – Second postcard from the island of stability