Invasion of the Body Snatchers

| Invasion of the Body Snatchers | |

|---|---|

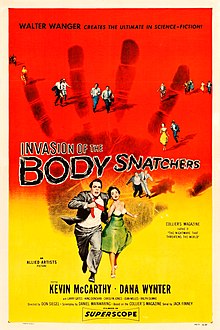

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Don Siegel |

| Produced by | Walter Wanger |

| Screenplay by | Daniel Mainwaring |

| Based on | The Body Snatchers by Jack Finney |

| Starring | |

| Music by | Carmen Dragon |

| Cinematography | Ellsworth Fredericks |

| Edited by | Robert S. Eisen |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Allied Artists Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 80 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $416,911[1] |

| Box office | $3 million |

Invasion of the Body Snatchers is a 1956 American science fiction horror film produced by Walter Wanger, directed by Don Siegel, that stars Kevin McCarthy and Dana Wynter. The black-and-white film, shot in Superscope, was partially done in a film noir style. Daniel Mainwaring adapted the screenplay from Jack Finney's 1954 science fiction novel The Body Snatchers.[2] The film was released by Allied Artists Pictures as a double feature with the British science fiction film The Atomic Man (and in some areas with Indestructible Man).[3]

The film's storyline concerns an extraterrestrial invasion that begins in the fictional California town of Santa Mira. Alien plant spores have fallen from space and grown into large seed pods, each one capable of reproducing a duplicate replacement copy of each human. As each pod reaches full development, it assimilates the physical characteristics, memories, and personalities of each sleeping person placed near it; these duplicates, however, are devoid of all human emotion. Little by little, a local doctor uncovers this "quiet" invasion and attempts to stop it.

The slang expression "pod people" that arose in late 20th century American culture references the emotionless duplicates seen in the film.[2] Invasion of the Body Snatchers was selected in 1994 for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress for being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant." [4]

Plot[edit]

Psychiatrist Dr. Hill is called to the emergency room of a California hospital, where a screaming man is being held in custody. Dr. Hill agrees to listen to his story. The man identifies himself as a doctor, and recounts, in flashback, the events leading up to his arrest and arrival at the hospital.

In the nearby town of Santa Mira, Dr. Miles Bennell sees a number of patients apparently suffering from Capgras delusion – the belief that their relatives have somehow been replaced with identical-looking impostors. Returning from a trip, Miles meets his former girlfriend, Becky Driscoll, who has recently come back to town after a divorce. Becky's cousin Wilma expresses the same fear about her Uncle Ira, with whom she lives. Psychiatrist Dr. Dan Kauffman assures Bennell that these cases are merely an "epidemic of mass hysteria".

That evening, Bennell's friend, Jack Belicec, finds a body with his exact physical features, though it appears not fully developed; later, another body is found in Becky's basement that is her exact duplicate. When Bennell calls Kauffman to the scene, the bodies have mysteriously disappeared, and Kauffman tells Bennell that he is falling for the same hysteria.

The following night, Bennell, Becky, Jack, and Jack's wife Teddy again find duplicates of themselves, emerging from giant seed pods in Bennell's greenhouse. They conclude that the townspeople are being replaced while asleep with exact physical copies. Miles tries to make a long-distance call to federal authorities for help, but the phone operator claims that all long-distance lines are busy. Jack and Teddy drive off to seek help in the next town. Bennell and Becky soon realize that all of the town's inhabitants have been replaced and are devoid of humanity. They hide at Bennell's office for the night, vowing to stay awake.

The next morning, from the office window, Bennell and Becky watch as truckloads of the giant pods arrive in the town center. They listen as Dumke directs the others to take them to neighboring towns to be planted and used to replace their populations. Kauffman and Jack, both of whom are now also "pod people", arrive at Bennell's office with new pods for Becky and Bennell. They reveal that an extraterrestrial life form is responsible for the invasion; the pods, capable of replicating any life form, traveled through space and landed in a field. After their takeover, they explain, humanity will lose all emotions and sense of individuality, creating a simplistic, stressless world.

After scuffling with and knocking out Kauffman, Jack and Dumke, Bennell and Becky escape the office. Outside, they pretend to be pod people, but Becky screams at a dog that is about to be hit by a car, exposing their humanity. A town alarm is sounded and they flee on foot, pursued by a mob of "pod people".

Exhausted, they manage to escape and hide in an abandoned mine outside town. Later, they hear music and Bennell leaves Becky briefly to investigate. Over a hill, he sees a large greenhouse farm with giant seed pods, being grown by the thousands and loaded onto trucks. Bennell returns to tell Becky, and upon kissing her he realizes, to his horror, that she fell asleep and is now one of them. Becky sounds the alarm as he runs away. He is again chased by the mob, and eventually finds himself on a crowded highway. After seeing a transport truck bound for San Francisco and Los Angeles filled with the pods, he frantically screams at the passing motorists, "They're here already! You're next! You're next!"

The flashback ends, and back at the hospital, Dr. Hill and the on-duty doctor dismiss Bennell's story as a lunatic rambling. As the doctors step into the hall to discuss, a truck driver is wheeled into the emergency room after being badly injured in an accident. The orderly tells the doctors that the man had to be dug out from under a load of giant seed pods. Finally believing Bennell's story, Dr. Hill calls for all roads in and out of Santa Mira to be barricaded, and alerts the FBI.

Cast[edit]

Starring:

- Kevin McCarthy as Dr. Miles Bennell

- Dana Wynter as Becky Driscoll

- King Donovan as Jack Belicec

- Carolyn Jones as Theodora "Teddy" Belicec

Featuring:

- Larry Gates as Dr. Dan Kauffman

- Virginia Christine as Wilma Lentz

- Ralph Dumke as Police Chief Nick Grivett

- Kenneth Patterson as Stanley Driscoll

- Guy Way as Officer Sam Janzek

- Jean Willes as Nurse Sally Withers

- Eileen Stevens as Anne Grimaldi

- Beatrice Maude as Grandma Grimaldi

- Whit Bissell (uncredited) as Dr. Hill

- Richard Deacon (uncredited) as Dr. Bassett

With:

- Bobby Clark as Jimmy Grimaldi

- Tom Fadden as Uncle Ira Lentz

- Everett Glass as Dr. Ed Pursey

- Dabbs Greer as Mac Lomax

- Sam Peckinpah as Charlie, the gas meter reader

Production[edit]

Novel and screenplay[edit]

Jack Finney's novel ends with the extraterrestrials, who have a life span of no more than five years, leaving Earth after they realize that humans are offering strong resistance, despite having little reasonable chance against the alien invasion.[2]

Budgeting and casting[edit]

Invasion of the Body Snatchers was originally scheduled for a 24-day shoot and a budget of US$454,864. The studio later asked Wanger to cut the budget significantly. The producer proposed a shooting schedule of 20 days and a budget of $350,000.[5]

Initially, Wanger considered Gig Young, Dick Powell, Joseph Cotten, and several others for the role of Miles. For Becky, he considered casting Anne Bancroft, Donna Reed, Kim Hunter, Vera Miles and others. With the lower budget, however, he abandoned these choices and cast Richard Kiley, who had just starred in The Phenix City Story for Allied Artists.[5] Kiley turned the role down and Wanger cast two relative newcomers in the lead roles: Kevin McCarthy, who had just starred in Siegel's An Annapolis Story, and Dana Wynter, who had done several major dramatic roles on television.[6]

Future director Sam Peckinpah had a small part as Charlie, a meter reader. Peckinpah was a dialogue coach on five Siegel films in the mid-1950s, including this one.[7]

Principal photography[edit]

Originally, producer Wanger and Siegel wanted to film Invasion of the Body Snatchers on location in Mill Valley, California, the town just north of San Francisco, that Jack Finney described in his novel.[5] In the first week of January 1955, Siegel, Wanger and screenwriter Daniel Mainwaring visited Finney to talk about the film version and to look at Mill Valley. The location proved too expensive and Siegel with Allied Artist executives found locations resembling Mill Valley in the Los Angeles area, including Sierra Madre, Chatsworth, Glendale, Los Feliz, Bronson and Beachwood Canyons, all of which would make up the town of "Santa Mira" for the film.[5] In addition to these outdoor locations, much of the film was shot in the Allied Artists studio on the east side of Hollywood.[2]

Invasion of the Body Snatchers was shot by cinematographer Ellsworth Fredericks in 23 days between March 23 and April 27, 1955. The cast and crew worked a six-day week with Sundays off.[5] The production went over schedule by three days because of night-for-night shooting that Siegel wanted. Additional photography took place in September 1955, filming a frame story on which the studio had insisted (see Original intended ending). The final budget was $382,190.[2]

Post-production[edit]

The project was originally named The Body Snatchers after the Finney serial.[8] However, Wanger wanted to avoid confusion with the 1945 Val Lewton film The Body Snatcher. The producer was unable to come up with a title and accepted the studio's choice, They Come from Another World and that was assigned in summer 1955. Siegel objected to this title and suggested two alternatives, Better Off Dead and Sleep No More, while Wanger offered Evil in the Night and World in Danger. None of these were chosen, and the studio settled on Invasion of the Body Snatchers in late 1955.[8] The film was released at the time in France under the mistranslated title "L'invasion des profanateurs de sépultures" (literally: Invasion of the defilers of tombs), which remains unchanged today.[9]

Wanger wanted to add a variety of speeches and prefaces.[10] He suggested a voice-over introduction for Miles.[11] While the film was being shot, Wanger tried to get permission in England to use a Winston Churchill quotation as a preface to the film. The producer sought out Orson Welles to voice the preface and a trailer for the film. He wrote speeches for Welles' opening on June 15, 1955, and worked to persuade Welles to do it, but was unsuccessful. Wanger considered science fiction author Ray Bradbury instead, but this did not happen, either.[11] Mainwaring eventually wrote the voice-over narration himself.[8]

The studio scheduled three film previews on the last days of June and the first day of July 1955.[11] According to Wanger's memos at the time, the previews were successful. Later reports by Mainwaring and Siegel, however, contradict this, claiming that audiences could not follow the film and laughed in the wrong places. In response the studio removed much of the film's humor, "humanity" and "quality," according to Wanger.[11] He scheduled another preview in mid-August that also did not go well. In later interviews Siegel pointed out that it was studio policy not to mix humor with horror.[11]

Wanger saw the final cut in December 1955 and protested the use of the Superscope aspect ratio.[8] Its use had been included in early plans for the film, but the first print was not made until December. Wanger felt that the film lost sharpness and detail. Siegel originally shot Invasion of the Body Snatchers in the 1.85:1 aspect ratio. Superscope was a post-production laboratory process designed to create an anamorphic print from non-anamorphic source material that would be projected at an aspect ratio of 2.00:1.[8][12]

Original intended ending [edit]

Both Siegel and Mainwaring were satisfied with the film as shot. It was originally meant to end with Miles screaming as truckloads of pods pass him by.[10] The studio, wary of a pessimistic conclusion, insisted on adding a prologue and epilogue suggesting a more optimistic outcome to the story, which is thus told mainly in flashback. In this version the film begins with a ranting Bennell in custody in a hospital emergency ward. He then tells a consulting psychiatrist (Whit Bissell) his story. In the closing scene pods are found at a highway accident, confirming his warning. The Federal Bureau of Investigation is notified.[2]

Mainwaring scripted this framing story and Siegel shot it on September 16, 1955, at the Allied Artists studio.[8] In a later interview Siegel complained, "The film was nearly ruined by those in charge at Allied Artists who added a preface and ending that I don't like".[13] In his autobiography Siegel added that "Wanger was very much against this, as was I. However, he begged me to shoot it to protect the film, and I reluctantly consented […]".[14]

While the Internet Movie Database states that the film had been revised to its original ending for a re-release in 1979,[15] Steve Biodrowski of Cinefantastique magazine notes that the film was still being shown with the complete footage, including a 2005 screening at the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, honoring director Don Siegel.[16]

Though disapproved of by most reviewers, George Turner (in American Cinematographer)[17] and Danny Peary (in Cult Movies)[18] endorsed the subsequently added frame story. Nonetheless, Peary emphasized that the added scenes changed significantly what he saw as the film's original intention.[citation needed]

Theatrical release[edit]

When the film was released domestically in February 1956, many theaters displayed several pods made of papier-mâché in theater lobbies and entrances, along with large lifelike black and white cutouts of McCarthy and Wynter running away from a crowd. The film made more than $1 million in the first month, and in 1956 alone made more than $2.5 million in the U.S.[2] When the British release (with cuts imposed by the British censors[19]) took place in late 1956, the film earned more than a half million dollars in ticket sales.[8]

Themes [edit]

Some reviewers saw in the story a commentary on the dangers facing America for turning a blind eye to McCarthyism, "Leonard Maltin speaks of a McCarthy-era subtext."[20] or of bland conformity in postwar Eisenhower-era America. Others viewed it as an allegory for the loss of personal autonomy in the Soviet Union or communist systems in general.[21]

For the BBC, David Wood summarized the circulating popular interpretations of the film as follows: "The sense of post-war, anti-communist paranoia is acute, as is the temptation to view the film as a metaphor for the tyranny of the McCarthy era."[22] Danny Peary in Cult Movies pointed out that the addition of the framing story had changed the film's stance from anti-McCarthyite to anti-communist.[18] Michael Dodd of The Missing Slate has called the movie "one of the most multifaceted horror films ever made", arguing that by "simultaneously exploiting the contemporary fear of infiltration by undesirable elements as well as a burgeoning concern over homeland totalitarianism in the wake of Senator Joseph McCarthy's notorious communist witch hunt, it may be the clearest window into the American psyche that horror cinema has ever provided".[23]

In An Illustrated History of the Horror Film, Carlos Clarens saw a trend manifesting itself in science fiction films, dealing with dehumanization and fear of the loss of individual identity, being historically connected to the end of "the Korean War and the well publicized reports of brainwashing techniques".[24] Comparing Invasion of the Body Snatchers with Robert Aldrich's Kiss Me Deadly and Orson Welles' Touch of Evil, Brian Neve found a sense of disillusionment rather than straightforward messages, with all three films being "less radical in any positive sense than reflective of the decline of [the screenwriters'] great liberal hopes".[25]

Despite a general agreement among film critics regarding these political connotations of the film, actor Kevin McCarthy said in an interview included on the 1998 DVD release that he felt no political allegory was intended. The interviewer stated that he had spoken with the author of the novel, Jack Finney, who professed no specific political allegory in the work. DVD commentary track, quoted in Feo Amante's homepage.[26]

In his autobiography, I Thought We Were Making Movies, Not History, Walter Mirisch writes: "People began to read meanings into pictures that were never intended. The Invasion of the Body Snatchers is an example of that. I remember reading a magazine article arguing that the picture was intended as an allegory about the communist infiltration of America. From personal knowledge, neither Walter Wanger nor Don Siegel, who directed it, nor Dan Mainwaring, who wrote the script nor original author Jack Finney, nor myself saw it as anything other than a thriller, pure and simple."[27]

Don Siegel spoke more openly of an existing allegorical subtext, but denied a strictly political point of view: "[…] I felt that this was a very important story. I think that the world is populated by pods and I wanted to show them. I think so many people have no feeling about cultural things, no feeling of pain, of sorrow. […] The political reference to Senator McCarthy and totalitarianism was inescapable but I tried not to emphasize it because I feel that motion pictures are primarily to entertain and I did not want to preach."[28] Film scholar J.P. Telotte wrote that Siegel intended for pods to be seductive; their spokesperson, a psychiatrist, was chosen to provide an authoritative voice that would appeal to the desire to "abdicate from human responsibility in an increasingly complex and confusing modern world."[29]

Reception [edit]

Critical reception[edit]

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (November 2016) |

Though Invasion of the Body Snatchers was largely ignored by critics on its initial run,[17] Filmsite.org ranked it as one of the best films of 1956.[30] The film holds a 98% approval rating and 9/10 rating at the film review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes. The site's consensus reads: "One of the best political allegories of the 1950s, Invasion of the Body Snatchers is an efficient, chilling blend of sci-fi and horror."[31]

In recent years critics such as Dan Druker of the Chicago Reader have called the film a "genuine Sci-Fi classic".[32] Leonard Maltin described Invasion of the Body Snatchers as "influential, and still very scary".[20] Time Out called the film one of the "most resonant" and "one of the simplest" of the genre.[33]

Legacy[edit]

Invasion of the Body Snatchers was selected in 1994 for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress as being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant".[34] In June 2008, the American Film Institute revealed its "Ten top Ten" — the best ten films in ten "classic" American film genres — after polling more than 1,500 people from the creative community. Invasion of the Body Snatchers was acknowledged as the ninth best film in the science fiction genre.[35] The film was also placed on AFI's AFI's 100 Years ... 100 Thrills, a list of America's most heart-pounding films.[36] The film was included on Bravo's 100 Scariest Movie Moments.[37] Similarly, the Chicago Film Critics Association named it the 29th scariest film ever made.[38] IGN ranked it as the 15th best sci-fi picture.[39]Time magazine included Invasion of the Body Snatchers on their list of 100 all-time best films,[40] the top 10 1950s Sci-Fi Movies,[41] and Top 25 Horror Films.[42]

Home media[edit]

The film was released on DVD in 1998 by U.S.-label Republic (an identical re-release by Artisan followed in 2002); it includes the Superscope version plus a 1.375:1 Academy ratio version. The latter is not the original full frame edition, but a pan and scan reworking of the Superscope edition that loses visual detail.[citation needed]

DVD editions exist on the British market (including a computer colorized version), German market (as Die Dämonischen) and Spanish market (as La Invasión de los Ladrones de Cuerpos).[citation needed]

Olive Films released a Blu-ray Disc Superscope version of the film in 2012.[43]

Remakes[edit]

The film was remade several times, including as Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1978), Body Snatchers (1993), The Invasion (2007), and Assimilate (2019 film).

An untitled fourth remake from Warner Bros is in development. David Leslie Johnson was signed to be the screenwriter.[44]

Related works[edit]

Robert A. Heinlein had previously developed this subject in his 1951 novel The Puppet Masters, written in 1950. The Puppet Masters was later plagiarized as the 1958 film The Brain Eaters, and adapted under contract in the 1994 film The Puppet Masters.

There are several thematically related works that followed Finney's 1955 novel The Body Snatchers, including Val Guest's Quatermass 2 and Gene Fowler's I Married a Monster from Outer Space.

A Looney Tunes parody of the film was released, entitled Invasion of the Bunny Snatchers (1992). The adaptation was directed by Greg Ford and places Bugs Bunny, Daffy Duck, Elmer Fudd, Yosemite Sam, and Porky Pig in the various roles of the story.

In 2018 theater company Team Starkid created the musical parody The Guy Who Didn’t Like Musicals, the story of a Midwestern town that is overtaken by an singing alien hive mind. The musical parodies numerous horror and musical tropes, while the main character also wears a suit reminiscent of Bennell's within the show.

The May 1981 issue of National Lampoon featured a parody titled "Invasion of the Money Snatchers"; the gentile population of Whiteville is taken over by pastrami sandwiches from outer space and turned into Jews.[45]

Further reading[edit]

- Grant, Barry Keith. 2010. Invasion of the body snatchers. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

See also[edit]

References[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ Bernstein 2000, p. 446.

- ^ a b c d e f g Warren 1982[page needed]

- ^ McGee, Mark Thomas; Robertson, R.J. (2013). "You Won't Believe Your Eyes". Bear Manor Media. ISBN 978-1-59393-273-2. Page 254

- ^ "Complete National Film Registry Listing | Film Registry | National Film Preservation Board | Programs at the Library of Congress | Library of Congress". Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA. Retrieved 2020-05-01.

- ^ a b c d e LaValley 1989, p. 25.

- ^ LaValley 1989, pp. 25-26.

- ^ Weddle 1994, pp. 116–119.

- ^ a b c d e f g LaValley 1989, p. 26.

- ^ Badmington, Neil (November 2010). "Pod almighty!; or, humanism, posthumanism, and the strange case of Invasion of the Body Snatchers". Textual Practice. 15 (1): 5–22. doi:10.1080/09502360010013848.

- ^ a b LaValley 1989, p. 125.

- ^ a b c d e LaValley 1989, p. 126.

- ^ Hart, Martin. "Superscope." Archived 2011-06-29 at the Wayback Machine The American WideScreen Museum, 2004. Retrieved: January 13, 2015.

- ^ Lovell, Alan (1975). Don Siegel: American Cinema. British Film Institute. p. 54. ISBN 978-0-85170-047-2.

- ^ Siegel 1993[page needed]

- ^ "Alternate versions: 'Invasion of the Body Snatchers'." Archived 2010-09-17 at the Wayback Machine IMDb. Retrieved: January 11, 2015.

- ^ Biodrowski, Steve. "Review: Invasion of the Body Snatchers." Archived 2017-08-22 at Wikiwix Cinefantastiqueonline.com. Retrieved: January 11, 2015.

- ^ a b Turner, George. "A Case of Insomnia." American Cinematographer (American Society of Cinematographers), Hollywood, March 1997.

- ^ a b Peary 1981[page needed]

- ^ "'Invasion of the Body Snatchers'." Archived 2012-08-29 at the Wayback Machine BBFC Web site. Retrieved: January 11, 2015.

- ^ a b Maltin's 2009, p. 685.

- ^ Carroll, Noel. "[…] it is the quintessential Fifties image of socialism", Soho News, December 21, 1978.

- ^ Wood, David. "'Invasion of the Body Snatchers'." Archived 2009-01-29 at the Wayback Machine BBC, May 1, 2001. Retrieved: January 11, 2015.

- ^ Dodd,Michael. "Safe Scares: How 9/11 caused the American Horror Remake Trend (Part One)." Archived 2014-10-11 at the Wayback Machine TheMissingSlate.com, August 31, 2014. Retrieved: January 11, 2015.

- ^ Clarens 1968[page needed]

- ^ Neve 1992[page needed]

- ^ Amante's, Feo. "Review: 'Invasion of the Body Snatchers.'" Archived 2006-10-07 at the Wayback Machine FeoAmante.com. Retrieved: January 11, 2015.

- ^ Mirisch 2008, pp. 39–40.

- ^ Interview with Don Siegel in Alan Lovell: Don Siegel. American Cinema, London 1975.

- ^ Telotte, J.P. "Human Artifice and the Science Fiction Film." Archived 2017-02-15 at the Wayback Machine Film Quarterly, Volume 36, Issue 3, Spring 1983, pg. 45. (via JSTOR subscription)(subscription required)

- ^ "The Greatest Films of 1956." Archived 2010-11-13 at the Wayback Machine AMC Filmsite.org. Retrieved: January 11, 2015.

- ^ "Movie Reviews, Pictures: 'Invasion of the Body Snatchers'." Archived 2010-09-16 at the Wayback Machine Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved: February 9, 2016.

- ^ Druker, Dan. "'Invasion of the Body Snatchers'." Archived 2013-05-20 at the Wayback Machine Chicago Reader. Retrieved: January 11, 2015.

- ^ "'Invasion of the Body Snatchers'." Archived 2009-02-02 at the Wayback Machine Time Out (magazine). Retrieved: January 11, 2015.

- ^ "Award Wins and Nominations: 'Invasion of the Body Snatchers'," Archived 2011-05-15 at the Wayback Machine IMDb. Retrieved: January 11, 2015.

- ^ "AFI's 10 Top 10." Archived 2012-03-12 at the Wayback Machine AFI.com. Retrieved: January 11, 2015.

- ^ "AFI's 100 Years... 100 Thrills." Archived 2011-07-16 at the Wayback Machine AFI. Retrieved: January 11, 2015.

- ^ "Bravo's The 100 Scariest Movie Moments." Bravo.com. Retrieved: January 11, 2015.

- ^ "Chicago Critics' Scariest Films." Archived 2015-06-04 at the Wayback Machine AltFilmGuide.com. Retrieved: January 11, 2015.

- ^ Fowler, Matt (January 22, 2020). "The 25 Best Sci Fi Movies". IGN. Retrieved January 22, 2020.

- ^ Schickel, Richard. "All-Time 100 Movies." Archived 2011-08-16 at the Wayback Machine Time, February 12, 2005. Retrieved: January 11, 2015.

- ^ Corliss, Richard. "1950s Sci-Fi Movies." Archived 2009-03-30 at the Wayback Machine Time, December 12, 2008; retrieved January 11, 2015.

- ^ "Top 25 Horror Films" Archived 2009-04-14 at the Wayback Machine, Time, October 29, 2007; retrieved January 11, 2015.

- ^ "DVD Savant Blu-ray Review: Invasion of the Body Snatchers". www.dvdtalk.com. Retrieved 2018-08-16.

- ^ McNary, Dave (19 July 2017). "'Invasion of the Body Snatchers' Remake in the Works at Warner Bros". variety.com. Archived from the original on 6 November 2017.

- ^ National Lampoon (May 1981) Archived 2017-10-13 at the Wayback Machine at the Grand Comics Database

Bibliography[edit]

- Bernstein, Matthew. Walter Wanger: Hollywood Independent. St. Paul, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2000. ISBN 978-0-52008-127-7.

- Clarens, Carlos. An Illustrated History of the Horror Film. Oakville, Ontario, Canada: Capricorn Books, 1968. ISBN 978-0-39950-111-1.

- LaValley, Al. Invasion of the Body Snatchers. New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press, 1989. ISBN 978-0-81351-461-1.

- Maltin, Leonard. Leonard Maltin's Movie Guide 2009. New York: New American Library, 2009 (originally published as TV Movies, then Leonard Maltin's Movie & Video Guide), First edition 1969, published annually since 1988. ISBN 978-0-451-22468-2.

- Mirisch, Walter. I Thought We Were Making Movies, Not History. Madison, Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin Press, 2008. ISBN 0-299-22640-9.

- Neve, Brian. Film and Politics in America: A Social Tradition. Oxon, UK: Routledge, 1992. ISBN 978-0-41502-620-8.

- Peary, Danny. Cult Movies: The Classics, the Sleepers, the Weird, and the Wonderful. New York: Dell Publishing, 1981. ISBN 978-0-385-28185-0.

- Siegel, Don. A Siegel Film. An Autobiography. London: Faber & Faber, 1993. ISBN 978-0-57117-831-5.

- Warren, Bill. Keep Watching the Skies: American Science Fiction Films of the Fifties, 21st Century Edition. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2009. ISBN 0-89950-032-3.

- Weddle, David. If They Move ... Kill 'Em! New York: Grove Press, 1994. ISBN 0-8021-3776-8.

External links[edit]

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Invasion of the Body Snatchers |

- Invasion of the Body Snatchers essay by Robert Sklar on the National Film Registry website [1]

- Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956) on IMDb

- Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956) at AllMovie

- Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956) at Rotten Tomatoes

- "Invasion of the Body Snatchers: A Tale for Our Times," by John W. Whitehead, Gadfly Online, November 26, 2001; discusses the political themes of the original film

- McCarthyism and the Movies

- Comparison of novel to the first three film adaptations

External links[edit]

- Ann Hornaday, "The 34 best political movies ever made" The Washington Post Jan. 23, 2020), ranked #17

- 1956 films

- English-language films

- 1956 horror films

- 1950s monster movies

- 1950s science fiction films

- 1950s science fiction horror films

- Alien invasions in films

- Allied Artists films

- American black-and-white films

- American films

- American science fiction horror films

- Apocalyptic films

- Body Snatchers films

- Films about extraterrestrial life

- Films about McCarthyism

- Films directed by Don Siegel

- Films produced by Walter Wanger

- Films scored by Carmen Dragon

- Films set in California

- Films set in fictional populated places

- Monogram Pictures films

- United States National Film Registry films