Maimonides

Maimonides Moses ben Maimon | |

|---|---|

18th-century depiction of Maimonides | |

| Born | 30 March[1] or 6 April[2] 1135 Possibly born 28 March or 4 April[3] 1138 |

| Died | 12 December 1204 |

Notable work | Mishneh Torah The Guide for the Perplexed |

| Partner(s) | (1) daughter of Nathaniel Baruch (2) daughter of Mishael Halevi |

| Era | Medieval philosophy |

| Region | Jewish philosophy |

| School | Aristotelianism |

Main interests | Religious law, Jewish law |

Notable ideas | Oath of Maimonides, Maimonides' rule, Golden mean, 13 principles of faith |

Influenced

| |

| Signature | |

Moses ben Maimon (Arabic: موسى بن ميمون), commonly known as Maimonides (/maɪˈmɒnɪdiːz/ my-MON-i-deez)[note 1] and also referred to by the acronym Rambam,[note 2] was a medieval Sephardic Jewish philosopher who became one of the most prolific and influential Torah scholars of the Middle Ages. In his time, he was also a preeminent astronomer and physician.[8][9][10][11] Born in Córdoba, Almoravid empire (present-day Spain) on Passover Eve, 1138,[12][13][14][15][16] he worked as a rabbi, physician, and philosopher in Morocco and Egypt. He died in Egypt on December 12, 1204, whence his body was taken to the lower Galilee and buried in Tiberias.[17][18]

During his lifetime, most Jews greeted Maimonides' writings on Jewish law and ethics with acclaim and gratitude, even as far away as Iraq and Yemen. Yet, while Maimonides rose to become the revered head of the Jewish community in Egypt, his writings also had vociferous critics, particularly in Spain. Nonetheless, he was posthumously acknowledged as among the foremost rabbinical decisors and philosophers in Jewish history, and his copious work comprises a cornerstone of Jewish scholarship. His fourteen-volume Mishneh Torah still carries significant canonical authority as a codification of Talmudic law. He is sometimes known as "ha Nesher ha Gadol" (the great eagle) in recognition of his outstanding status as a bona fide exponent of the Oral Torah.

Aside from being revered by Jewish historians, Maimonides also figures very prominently in the history of Islamic and Arab sciences and is mentioned extensively in studies. Influenced by Al-Farabi, Avicenna, and his contemporary Averroes, he became a prominent philosopher and polymath in both the Jewish and Islamic worlds.

Name[edit]

His full Hebrew name is Rabbi Moshe ben Maimon (רבי משה בן מימון), whose acronym forms "Rambam" (רמב״ם). His full Arabic name is Abū ʿImrān Mūsā bin Maimūn bin ʿUbaidallāh al-Qurtabī (ابو عمران موسى بن ميمون بن عبيد الله القرطبي), or Mūsā bin Maymūn (موسى بن ميمون) for short. The portion bin ʿUbaidallāh should not imply that Maimon's father was named Obadiah, instead bin ʿUbaidallāh is treated as Maimonides' surname, as Obadiah was the name of his earliest direct ancestor. In Latin, the Hebrew ben (son of) becomes the Greek-style patronymic suffix -ides, forming "Moses Maimonides".

Biography[edit]

Early years[edit]

Maimonides was born 1138 in Córdoba, Andalusia in the Berber Muslim-ruled Almoravid Empire during what some scholars consider to be the end of the golden age of Jewish culture in the Iberian Peninsula, after the first centuries of the Moorish rule. His father Maimon ben Joseph, was a spanish dayyan (Jewish judge), whos family claimed direct paternal descent from Simeon ben Judah ha-Nasi, and thus from the Davidic line. Maimonides later stated that there is 38 generations between him and Judah ha-Nasi.[19][20] At an early age, Maimonides developed an interest in sciences and philosophy. He read those Greek philosophers accessible in Arabic translations, and was deeply immersed in the sciences and learning of Islamic culture.[21]

Maimonides was not known as a supporter of Kabbalah, although a strong intellectual type of mysticism has been discerned in his philosophy.[22] He expressed disapproval of poetry, the best of which he declared to be false, since it was founded on pure invention. This sage, who was revered for his personality as well as for his writings, led a busy life, and wrote many of his works while travelling or in temporary accommodation.[23] Maimonides studied Torah under his father, who had in turn studied under Rabbi Joseph ibn Migash, a student of Isaac Alfasi.

Exile[edit]

Another Berber dynasty, the Almohads, conquered Córdoba in 1148 and abolished dhimmi status (i.e., state protection of non-Muslims ensured through payment of a tax, the jizya) in some[which?] of their territories. The loss of this status left the Jewish and Christian communities with conversion to Islam, death, or exile.[23] Many Jews were forced to convert, but due to suspicion by the authorities of fake conversions, the new converts had to wear identifying clothing that set them apart and made them subject to public scrutiny.[24][25]

Maimonides's family, along with most other Jews,[dubious ] chose exile. Some say, though, that it is likely that Maimonides feigned a conversion to Islam before escaping.[26] This forced conversion was ruled legally invalid under Islamic law when brought up by a rival in Egypt.[27] For the next ten years, Maimonides moved about in southern Spain, eventually settling in Fez in Morocco. During this time, he composed his acclaimed commentary on the Mishnah, during the years 1166–1168.[28]

Following this sojourn in Morocco, together with two sons,[29] he sojourned in the Land of Israel before settling in Fustat in Fatimid Caliphate-controlled Egypt around 1168. While in Cairo, he studied in a yeshiva attached to a small synagogue, which now bears his name.[30] In the Land of Israel, he prayed at the Temple Mount. He wrote that this day of visiting the Temple Mount was a day of holiness for him and his descendants.[31]

Maimonides shortly thereafter was instrumental in helping rescue Jews taken captive during the Christian Amalric of Jerusalem's siege of the southeastern Nile Delta town of Bilbeis. He sent five letters to the Jewish communities of Lower Egypt asking them to pool money together to pay the ransom. The money was collected and then given to two judges sent to Palestine to negotiate with the Crusaders. The captives were eventually released.[32]

Death of his brother[edit]

Following this triumph, the Maimonides family, hoping to increase their wealth, gave their savings to his brother, the youngest son David ben Maimon, a merchant. Maimonides directed his brother to procure goods only at the Sudanese port of ‘Aydhab. After a long arduous trip through the desert, however, David was unimpressed by the goods on offer there. Against his brother's wishes, David boarded a ship for India, since great wealth was to be found in the East.[33] Before he could reach his destination, David drowned at sea sometime between 1169 and 1177. The death of his brother caused Maimonides to become sick with grief.

In a letter (discovered later in the Cairo Geniza), he wrote:

The greatest misfortune that has befallen me during my entire life—worse than anything else—was the demise of the saint, may his memory be blessed, who drowned in the Indian sea, carrying much money belonging to me, to him, and to others, and left with me a little daughter and a widow. On the day I received that terrible news I fell ill and remained in bed for about a year, suffering from a sore boil, fever, and depression, and was almost given up. About eight years have passed, but I am still mourning and unable to accept consolation. And how should I console myself? He grew up on my knees, he was my brother, [and] he was my student.[34]

Nagid[edit]

Around 1171, Maimonides was appointed the Nagid of the Egyptian Jewish community.[30] Arabist Shelomo Dov Goitein believes the leadership he displayed during the ransoming of the Crusader captives led to this appointment.[35] With the loss of the family funds tied up in David's business venture, Maimonides assumed the vocation of physician, for which he was to become famous. He had trained in medicine in both Córdoba and in Fez. Gaining widespread recognition, he was appointed court physician to the Grand Vizier al-Qadi al Fadil, then to Sultan Saladin, after whose death he remained a physician to the Ayyubid dynasty.[36]

In his medical writings, Maimonides described many conditions, including asthma, diabetes, hepatitis, and pneumonia, and he emphasized moderation and a healthy lifestyle.[37] His treatises became influential for generations of physicians. He was knowledgeable about Greek and Arabic medicine, and followed the principles of humorism in the tradition of Galen. He did not blindly accept authority but used his own observation and experience.[37] Julia Bess Frank indicates that Maimonides in his medical writings sought to interpret works of authorities so that they could become acceptable.[36] Maimonides displayed in his interactions with patients attributes that today would be called intercultural awareness and respect for the patient's autonomy.[38] Although he frequently wrote of his longing for solitude in order to come closer to God and to extend his reflections – elements considered essential in his philosophy to the prophetic experience -he gave over most of his time to caring for others.[39] In a famous letter, Maimonides describes his daily routine. After visiting the Sultan's palace, he would arrive home exhausted and hungry, where "I would find the antechambers filled with gentiles and Jews … I would go to heal them, and write prescriptions for their illnesses … until the evening … and I would be extremely weak."[40]

As he goes on to say in this letter, even on Shabbat he would receive members of the community. It is remarkable that he managed to write extended treatises, including not only medical and other scientific studies but some of the most systematically thought-through and influential treatises on halakha (rabbinic law) and Jewish philosophy of the Middle Ages.[41]

Joseph Karo later praised Maimonides, writing of him, "Maimonides is the greatest of the decisors [of Jewish law], and all communities of the Land of Israel and of Arabia and of the Maghreb base their practices after him, and have taken him upon themselves as their rabbi."[42]

In 1173/4, Maimonides wrote his famous Epistle to Yemen.[43] It has been suggested that his "incessant travail" undermined his own health and brought about his death at 69 (although this is a normal lifespan).[44]

Death[edit]

Maimonides died on December 12, 1204 (20th of Tevet 4965) in Fustat. It is widely believed that he was briefly buried in the beth midrash of the synagogue courtyard, and that, soon after, in accordance with his wishes, his remains were exhumed and taken to Tiberias, where he was reinterred.[45] The Tomb of Maimonides on the western shore of the Sea of Galilee in Israel marks his grave. This location for his final resting-place has been debated, for in the Jewish Cairene community, a tradition holds that he remained buried in Egypt.[46]

Maimonides and his wife, the daughter of Mishael ben Yeshayahu Halevi, had one child who survived into adulthood,[47] Abraham Maimonides, who became recognized as a great scholar. He succeeded Maimonides as Nagid and as court physician at the age of eighteen. Throughout his career, he defended his father's writings against all critics. The office of Nagid was held by the Maimonides family for four successive generations until the end of the 14th century.

Maimonides is widely respected in Spain, and a statue of him was erected near the Córdoba Synagogue.

Maimonides is sometimes said to be a descendant of King David, although he never made such a claim.[48][49]

13 principles of faith[edit]

In his commentary on the Mishnah (tractate Sanhedrin, chapter 10), Maimonides formulates his "13 principles of faith". They summarized what he viewed as the required beliefs of Judaism:

- The existence of God.

- God's unity and indivisibility into elements.

- God's spirituality and incorporeality.

- God's eternity.

- God alone should be the object of worship.

- Revelation through God's prophets.

- The preeminence of Moses among the prophets.

- That the entire Torah (both the Written and Oral law) are of Divine origin and were dictated to Moses by God on Mt. Sinai.

- The Torah given by Moses is permanent and will not be replaced or changed.

- God's awareness of all human actions and thoughts.

- Reward of righteousness and punishment of evil.

- The coming of the Jewish Messiah.

- The resurrection of the dead.

Maimonides compiled the principles from various Talmudic sources. These principles were controversial when first proposed, evoking criticism by Rabbis Hasdai Crescas and Joseph Albo, and were effectively ignored by much of the Jewish community for the next few centuries.[50] However, these principles have become widely held and are considered to be the cardinal principals of faith for Orthodox Jews.[51][52] Two poetic restatements of these principles (Ani Ma'amin and Yigdal) eventually became canonized in many editions of the "Siddur" (Jewish prayer book). Maimonides famously omitted any mention of these "Principles of Faith" from his later works, the Mishneh Torah, and the Guide for the Perplexed, leading some to suggest that either he retracted his earlier position, or that these principles are descriptive rather than prescriptive.[citation needed]

Legal works[edit]

With Mishneh Torah, Maimonides composed a code of Jewish law with the widest-possible scope and depth. The work gathers all the binding laws from the Talmud, and incorporates the positions of the Geonim (post-Talmudic early Medieval scholars, mainly from Mesopotamia).

Later codes of Jewish law, e.g. Arba'ah Turim by Rabbi Jacob ben Asher and Shulchan Aruch by Rabbi Yosef Karo, draw heavily on Mishneh Torah: both often quote whole sections verbatim. However, it met initially with much opposition.[53] There were two main reasons for this opposition. First, Maimonides had refrained from adding references to his work for the sake of brevity; second, in the introduction, he gave the impression of wanting to "cut out" study of the Talmud,[54] to arrive at a conclusion in Jewish law, although Maimonides later wrote that this was not his intent. His most forceful opponents were the rabbis of Provence (Southern France), and a running critique by Rabbi Abraham ben David (Raavad III) is printed in virtually all editions of Mishneh Torah. It was still recognized as a monumental contribution to the systemized writing of halakha. Throughout the centuries, it has been widely studied and its halakhic decisions have weighed heavily in later rulings.

In response to those who would attempt to force followers of Maimonides and his Mishneh Torah to abide by the rulings of his own Shulchan Aruch or other later works, Rabbi Yosef Karo wrote: "Who would dare force communities who follow the Rambam to follow any other decisor, early or late? … The Rambam is the greatest of the decisors, and all the communities of the Land of Israel and the Arabistan and the Maghreb practice according to his word, and accepted him as their rabbi."[55]

An oft-cited legal maxim from his pen is: "It is better and more satisfactory to acquit a thousand guilty persons than to put a single innocent one to death." He argued that executing a defendant on anything less than absolute certainty would lead to a slippery slope of decreasing burdens of proof, until we would be convicting merely according to the judge's caprice.[56]

Scholars specializing in the study of the history and subculture of Judaism in premodern China (Sino-Judaica) have noted surprising similarities between this work and the liturgy of the Kaifeng Jews, descendants of Persian merchants who settled in the Middle Kingdom during the early Song dynasty.[57] Beyond scriptural similarities, Michael Pollak comments the Jews' Pentateuch was divided into 53 sections according to the Persian style.[58] He also points out:

There is no proof, to be sure, that Kaifeng Jewry ever had direct access to the works of "the Great Eagle," but it would have had ample time and opportunity to acquire or become acquainted with them well before its reservoir of Jewish learning began to run out. Nor do the Maimonidean leanings of the kehillah contradict the historical evidence that has the Jews arriving in Kaifeng no later than 1126, the year in which the Sung fled the city—and nine years before Maimonides was born. In 1163, when the kehillah built the first of its synagogues, Maimonides was only twenty-eight years old, so that it is highly unlikely that even his earliest authoritative teachings could by then have reached China.[59]

Tzedakah (charity)[edit]

One of the most widely referred to sections of the Mishneh Torah is the section dealing with tzedakah. In Hilkhot Matanot Aniyim (Laws about Giving to Poor People), Chapter 10:7–14, Maimonides lists his famous Eight Levels of Giving (where the first level is most preferable, and the eighth the least):[60]

- Giving an interest-free loan to a person in need; forming a partnership with a person in need; giving a grant to a person in need; finding a job for a person in need; so long as that loan, grant, partnership, or job results in the person no longer living by relying upon others.

- Giving tzedakah anonymously to an unknown recipient via a person (or public fund) which is trustworthy, wise, and can perform acts of tzedakah with your money in a most impeccable fashion.

- Giving tzedakah anonymously to a known recipient.

- Giving tzedakah publicly to an unknown recipient.

- Giving tzedakah before being asked.

- Giving adequately after being asked.

- Giving willingly, but inadequately.

- Giving "in sadness" (giving out of pity): It is thought that Maimonides was referring to giving because of the sad feelings one might have in seeing people in need (as opposed to giving because it is a religious obligation). Other translations say "Giving unwillingly."

Philosophy[edit]

Through The Guide for the Perplexed (which was initially written in Arabic as Dalālat al-ḥāʾirīn) and the philosophical introductions to sections of his commentaries on the Mishna, Maimonides exerted an important influence on the Scholastic philosophers, especially on Albertus Magnus, Thomas Aquinas and Duns Scotus. He was a Jewish Scholastic. Educated more by reading the works of Arab Muslim philosophers than by personal contact with Arabian teachers, he acquired an intimate acquaintance not only with Arab Muslim philosophy, but with the doctrines of Aristotle. Maimonides strove to reconcile Aristotelianism and science with the teachings of the Torah.[61] In his Guide for the Perplexed, he often explains the function and purpose of the statutory provisions contained in the Torah against the backdrop of the historical conditions. Maimonides is said to have been influenced by Asaph the Jew, who was the first Hebrew medical writer.

Theology[edit]

Maimonides equated the God of Abraham to what philosophers refer to as the Necessary Being. God is unique in the universe, and the Torah commands that one love and fear God (Deut 10:12) on account of that uniqueness. To Maimonides, this meant that one ought to contemplate God's works and to marvel at the order and wisdom that went into their creation. When one does this, one inevitably comes to love God and to sense how insignificant one is in comparison to God. This is the basis of the Torah.[62]

The principle that inspired his philosophical activity was identical to a fundamental tenet of scholasticism: there can be no contradiction between the truths which God has revealed and the findings of the human mind in science and philosophy. Maimonides primarily relied upon the science of Aristotle and the teachings of the Talmud, commonly finding basis in the former for the latter.[63]

Maimonides' admiration for the Neoplatonic commentators led him to doctrines which the later Scholastics did not accept. For instance, Maimonides was an adherent of apophatic theology. In this theology, one attempts to describe God through negative attributes. For instance, one should not say that God exists in the usual sense of the term; it can be said that God is not non-existent. We should not say that "God is wise"; but we can say that "God is not ignorant," i.e., in some way, God has some properties of knowledge. We should not say that "God is One," but we can state that "there is no multiplicity in God's being." In brief, the attempt is to gain and express knowledge of God by describing what God is not, rather than by describing what God "is."[64]

Maimonides argued adamantly that God is not corporeal. This was central to his thinking about the sin of idolatry. Maimonides insisted that all of the anthropomorphic phrases pertaining to God in sacred texts are to be interpreted metaphorically.[64]

Character development[edit]

Maimonides taught about the developing one's moral character. Although his life predated the modern concept of a personality, Maimonides believed that each person has an innate disposition along an ethical and emotional spectrum. Although one's disposition is often determined by factors outside of one's control, human beings have free will to choose to behave in ways that build character.[65] He wrote, "One is obligated to conduct his affairs with others in a gentle and pleasing manner."[66] Maimonides advised those with anti-social character traits ought to identify those traits and then make a conscious effort to behave in the opposite way. For example, an arrogant person should practice humility.[67] If the circumstances of one's environment are such that it is impossible to behave ethically, one must move to a new location.[68]

Prophecy[edit]

He agrees with "the Philosopher" (Aristotle) in teaching that the use of logic is the "right" way of thinking. In order to build an inner understanding of how to know God, every human being must, by study, meditation and uncompromising strong will, attain the degree of complete logical, spiritual and physical perfection required in the prophetic state. Here he rejects previous ideas (especially portrayed by Rabbi Yehuda Halevi in "Hakuzari") that in order to become a prophet, God must intervene. Maimonides claims that any man or woman[69] has the potential to become a prophet (not just Jews) and that in fact it is the purpose of the human race.

The problem of evil[edit]

Maimonides wrote on theodicy (the philosophical attempt to reconcile the existence of a God with the existence of evil). He took the premise that an omnipotent and good God exists.[70][71][72][73] In The Guide for the Perplexed, Maimonides writes that all the evil that exists within human beings stems from their individual attributes, while all good comes from a universally shared humanity (Guide 3:8). He says that there are people who are guided by higher purpose, and there are those who are guided by physicality and must strive to find the higher purpose with which to guide their actions.

To justify the existence of evil, assuming God is both omnipotent and omnibenevolent, Maimonides postulates that one who created something by causing its opposite not to exist is not the same as creating something that exists; so evil is merely the absence of good. God did not create evil, rather God created good, and evil exists where good is absent (Guide 3:10). Therefore, all good is divine invention, and evil both is not and comes secondarily.

Maimonides contests the common view that evil outweighs good in the world. He says that if one were to examine existence only in terms of humanity, then that person may observe evil to dominate good, but if one looks at the whole of the universe, then he sees good is significantly more common than evil (Guide 3:12). Man, he reasons, is too insignificant a figure in God's myriad works to be their primary characterizing force, and so when people see mostly evil in their lives, they are not taking into account the extent of positive Creation outside of themselves.

Maimonides believes that there are three types of evil in the world: evil caused by nature, evil that people bring upon others, and evil man brings upon himself (Guide 3:12). The first type of evil Maimonides states is the rarest form, but arguably of the most necessary—the balance of life and death in both the human and animal worlds itself, he recognizes, is essential to God's plan. Maimonides writes that the second type of evil is relatively rare, and that humanity brings it upon itself. The third type of evil humans bring upon themselves and is the source of most of the ills of the world. These are the result of people falling victim to their physical desires. To prevent the majority of evil which stems from harm we do to ourselves, we must learn how to ignore our bodily urges.

Skepticism of astrology[edit]

Maimonides answered an inquiry concerning astrology, addressed to him from Marseille.[74] He responded that man should believe only what can be supported either by rational proof, by the evidence of the senses, or by trustworthy authority. He affirms that he had studied astrology, and that it does not deserve to be described as a science. He ridicules the concept that the fate of a man could be dependent upon the constellations; he argues that such a theory would rob life of purpose, and would make man a slave of destiny.[75]

True beliefs versus necessary beliefs[edit]

In The Guide for the Perplexed Book III, Chapter 28,[76] Maimonides draws a distinction between "true beliefs," which were beliefs about God that produced intellectual perfection, and "necessary beliefs," which were conducive to improving social order. Maimonides places anthropomorphic personification statements about God in the latter class. He uses as an example the notion that God becomes "angry" with people who do wrong. In the view of Maimonides (taken from Avicenna), God does not become angry with people, as God has no human passions; but it is important for them to believe God does, so that they desist from doing wrong.

Eschatology[edit]

The World to Come[edit]

Maimonides distinguishes two kinds of intelligence in man, the one material in the sense of being dependent on, and influenced by, the body, and the other immaterial, that is, independent of the bodily organism. The latter is a direct emanation from the universal active intellect; this is his interpretation of the noûs poietikós of Aristotelian philosophy. It is acquired as the result of the efforts of the soul to attain a correct knowledge of the absolute, pure intelligence of God.

The knowledge of God is a form of knowledge which develops in us the immaterial intelligence, and thus confers on man an immaterial, spiritual nature. This confers on the soul that perfection in which human happiness consists, and endows the soul with immortality. One who has attained a correct knowledge of God has reached a condition of existence, which renders him immune from all the accidents of fortune, from all the allurements of sin, and from death itself. Man is in a position to work out his own salvation and his immortality.

Spinoza's doctrine of immortality was strikingly similar. But Spinoza teaches that the way to attain the knowledge which confers immortality is the progress from sense-knowledge through scientific knowledge to philosophical intuition of all things sub specie æternitatis, while Maimonides holds that the road to perfection and immortality is the path of duty as described in the Torah and the rabbinic understanding of the oral law.

The Messianic era[edit]

Perhaps one of Maimonides's most highly acclaimed and renowned writings is his treatise on the Messianic era, written originally in Judeo-Arabic and which he elaborates on in great detail in his Commentary on the Mishnah (Introduction to the 10th chapter of tractate Sanhedrin, also known as Pereḳ Ḥeleḳ). (Open window for text)

| Full text of Maimonides on the Messianic Era | |

|---|---|

|

Resurrection[edit]

Religious Jews believed in immortality in a spiritual sense, and most believed that the future would include a messianic era and a resurrection of the dead. This is the subject of Jewish eschatology. Maimonides wrote much on this topic, but in most cases he wrote about the immortality of the soul for people of perfected intellect; his writings were usually not about the resurrection of dead bodies. Rabbis of his day were critical of this aspect of this thought, and there was controversy over his true views.[77]

Eventually, Maimonides felt pressured to write a treatise on the subject, known as "The Treatise on Resurrection." In it, he wrote that those who claimed that he believed the verses of the Hebrew Bible referring to the resurrection were only allegorical were spreading falsehoods. Maimonides asserts that belief in resurrection is a fundamental truth of Judaism about which there is no disagreement.[78]

While his position on the World to Come (non-corporeal eternal life as described above) may be seen as being in contradiction with his position on bodily resurrection, Maimonides resolved them with a then unique solution: Maimonides believed that the resurrection was not permanent or general. In his view, God never violates the laws of nature. Rather, divine interaction is by way of angels, whom Maimonides often regards to be metaphors for the laws of nature, the principles by which the physical universe operates, or Platonic eternal forms. [This is not always the case. In Hilchot Yesodei HaTorah Chaps. 2–4, Maimonides describes angels that are actually created beings.] Thus, if a unique event actually occurs, even if it is perceived as a miracle, it is not a violation of the world's order.[79]

In this view, any dead who are resurrected must eventually die again. In his discussion of the 13 principles of faith, the first five deal with knowledge of God, the next four deal with prophecy and the Torah, while the last four deal with reward, punishment and the ultimate redemption. In this discussion Maimonides says nothing of a universal resurrection. All he says it is that whatever resurrection does take place, it will occur at an indeterminate time before the world to come, which he repeatedly states will be purely spiritual.

Maimonides and Kabbalah[edit]

In The Guide for the Perplexed, Maimonides declares his intention to conceal from the average reader his explanations of Sod [80] esoteric meanings of Torah. The nature of these "secrets" is debated. Religious Jewish rationalists, and the mainstream academic view, read Maimonides' Aristotelianism as a mutually-exclusive alternative metaphysics to Kabbalah.[81] Some academics hold that Maimonides' project fought against the Proto-Kabbalah of his time.[82] However, many Kabbalists and their heirs to read Maimonides according to Kabbalah or as an actual covert subscriber to Kabbalah,[83] due to the similarities between the Kabbalistic approach and Maimonides' approach toward interpreting the Bible with metaphor, Maimonides' understanding of God through attributes of action, thought and negative attributes, Maimonides' description of the roles of the imagination and intellect in life, sin, and prophesy, Maimonides' assertion that the commandments have a function that can be understood, Maimonides' description of a 3-tiered cosmic order whereby God's will is implemented through a system of angels.[citation needed] According to this, he employed rationalism to defend Judaism rather than limit inquiry of Sod only to rationalism. His rationalism, if not taken as an opposition,[84] also assisted the Kabbalists, purifying their transmitted teaching from mistaken corporeal interpretations that could have been made from Hekhalot literature,[85] though Kabbalists held that their theosophy alone allowed human access to Divine mysteries.[86]

The Oath of Maimonides[edit]

The Oath of Maimonides is a document about the medical calling and recited as a substitute for the Hippocratic Oath. It is not to be confused with a more lengthy Prayer of Maimonides. These documents may not have been written by Maimonides, but later.[36] The Prayer appeared first in print in 1793 and has been attributed to Markus Herz, a German physician, pupil of Immanuel Kant.[87]

Views on circumcision[edit]

In The Guide for the Perplexed, Maimonides proposes that two important purposes of circumcision (brit milah) are to temper sexual desire and to join in an affirmation of faith and the covenant of Abraham:[88][89]

As regards circumcision, I think that one of its objects is to limit sexual intercourse, and to weaken the organ of generation as far as possible, and thus cause man to be moderate. Some people believe that circumcision is to remove a defect in man's formation; but every one can easily reply: How can products of nature be deficient so as to require external completion, especially as the use of the fore-skin to that organ is evident. This commandment has not been enjoined as a complement to a deficient physical creation, but as a means for perfecting man's moral shortcomings. The [degree of] bodily damage caused to that organ is exactly that which is desired; it does not interrupt any vital function, nor does it destroy the power of generation. Circumcision simply counteracts excessive lust; for there is no doubt that circumcision weakens the power of sexual excitement, and sometimes lessens the natural enjoyment: the organ necessarily becomes weak when it loses blood and is deprived of its covering from the beginning, and our Sages (Beresh. Rabba, c. 80) say distinctly: It is hard for a woman, with whom an uncircumcised had sexual intercourse, to separate from him. [Tempering lust] is, as I believe, the best reason for the commandment concerning circumcision. And who was the first to perform this commandment? Abraham, our father! of whom it is well known how he feared sin; it is described by our Sages in reference to the words, "Behold, now I know that thou art a fair woman to look upon" (Gen. xii. 11). There is, however, another important object in this commandment. It gives to all members of the same faith, i.e., to all believers in the Unity of God, a common bodily sign, so that it is impossible for any one that is a stranger, to say that he belongs to them. For sometimes people say so for the purpose of obtaining some advantage, or in order to make some attack upon the Jews. No one, however, should circumcise himself or his son for any other reason but pure faith; for circumcision is not like an incision on the leg, or a burning in the arm, but a very difficult operation. It is also a fact that there is much mutual love and assistance among people that are united by the same sign when they consider it as [the symbol of] a covenant. Circumcision is likewise the [symbol of the] covenant which Abraham made in connexion with the belief in God's Unity. So also every one that is circumcised enters the covenant of Abraham to believe in the unity of God, in accordance with the words of the Law, "To be a God unto thee, and to thy seed after thee" (Gen. xvii. 7). This purpose of the circumcision is as important as the first, and perhaps more important.

— Maimonides, The Guide to the Perplexed (1190)

Influence[edit]

Maimonides' Mishneh Torah is considered by Jews even today as one of the chief authoritative codifications of Jewish law and ethics. It is exceptional for its logical construction, concise and clear expression and extraordinary learning, so that it became a standard against which other later codifications were often measured.[90] It is still closely studied in rabbinic yeshivot (academies). A popular medieval saying that also served as his epitaph states, From Mosheh (of the Torah) to Mosheh (Maimonides) there was none like Mosheh. It chiefly referred to his rabbinic writings.

But Maimonides was also one of the most influential figures in medieval Jewish philosophy. His brilliant adaptation of Aristotelian thought to Biblical faith deeply impressed later Jewish thinkers, and had an unexpected immediate historical impact.[91] Some more acculturated Jews in the century that followed his death, particularly in Spain, sought to apply Maimonides's Aristotelianism in ways that undercut traditionalist belief and observance, giving rise to an intellectual controversy in Spanish and southern French Jewish circles.[92] The intensity of debate spurred Catholic Church interventions against "heresy" and a general confiscation of rabbinic texts. In reaction, the more radical interpretations of Maimonides were defeated. At least amongst Ashkenazi Jews, there was a tendency to ignore his specifically philosophical writings and to stress instead the rabbinic and halakhic writings. These writings often included considerable philosophical chapters or discussions in support of halakhic observance; David Hartman observes that Maimonides clearly expressed "the traditional support for a philosophical understanding of God both in the Aggadah of Talmud and in the behavior of the hasid [the pious Jew]."[93] Maimonidean thought continues to influence traditionally observant Jews.[94][95]

The most rigorous medieval critique of Maimonides is Hasdai Crescas's Or Adonai. Crescas bucked the eclectic trend, by demolishing the certainty of the Aristotelian world-view, not only in religious matters but also in the most basic areas of medieval science (such as physics and geometry). Crescas's critique provoked a number of 15th-century scholars to write defenses of Maimonides. A partial translation of Crescas was produced by Harry Austryn Wolfson of Harvard University in 1929.

Because of his path-finding synthesis of Aristotle and Biblical faith, Maimonides had a fundamental influence on the great Christian theologian Saint Thomas Aquinas.[96] Aquinas refers specifically to Maimonides in several of his works, including the Commentary on the Sentences.

Maimonides's combined abilities in the fields of theology, philosophy and medicine make his work attractive today as a source during discussions of evolving norms in these fields, particularly medicine. An example is the modern citation of his method of determining death of the body in the controversy regarding declaration of death to permit organ donation for transplantation.[97]

Maimonides and the Modernists[edit]

Maimonides remains one of the most widely debated Jewish thinkers among modern scholars. He has been adopted as a symbol and an intellectual hero by almost all major movements in modern Judaism, and has proven important to philosophers such as Leo Strauss; and his views on the importance of humility have been taken up by modern humanist philosophers.

In academia, particularly within the area of Jewish Studies, the teaching of Maimonides has been dominated by traditional scholars, generally Orthodox, who place a very strong emphasis on Maimonides as a rationalist; one result is that certain sides of Maimonides's thought, including his opposition to anthropocentrism, have been obviated.[citation needed] There are movements in some postmodern circles to claim Maimonides for other purposes, as within the discourse of ecotheology.[98] Maimonides's reconciliation of the philosophical and the traditional has given his legacy an extremely diverse and dynamic quality.

Tributes and memorials[edit]

Maimonides has been memorialized in numerous ways. For example, one of the Learning Communities at the Tufts University School of Medicine bears his name. There is also Maimonides School in Brookline, Massachusetts, Maimonides Academy School in Los Angeles, California, Lycée Maïmonide in Casablanca, the Brauser Maimonides Academy in Hollywood, Florida,[99] and Maimonides Medical Center in Brooklyn, New York.

In 2004, conferences were held at Yale, Florida International University, Penn State, and the Rambam Hospital in Haifa, Israel, which is named after him. To commemorate the 800th anniversary of his death, Harvard University issued a memorial volume.[100] In 1953, the Israel Postal Authority issued a postage stamp of Maimonides, pictured.

In March 2008, during the Euromed Conference of Ministers of Tourism, The Tourism Ministries of Israel, Morocco and Spain agreed to work together on a joint project that will trace the footsteps of the Rambam and thus boost religious tourism in the cities of Córdoba, Fes and Tiberias.[101]

Between December 2018 and January 2019 the Israel Museum held a special exhibit dedicated to the writings of Maimonides.[102]

Works and bibliography[edit]

Judaic and philosophical works[edit]

Maimonides composed works of Jewish scholarship, rabbinic law, philosophy, and medical texts. Most of Maimonides's works were written in Judeo-Arabic. However, the Mishneh Torah was written in Hebrew. His Jewish texts were:

- Commentary on the Mishna (Arabic Kitab al-Siraj, translated into Hebrew as Pirush Hamishnayot), written in Classical Arabic using the Hebrew alphabet. This was the first full commentary ever written on the entire Mishnah, and it enjoyed great popularity both in its Arabic original and its medieval Hebrew translation. The commentary includes three philosophical introductions which were also highly influential:

- The Introduction to the Mishnah deals with the nature of the oral law, the distinction between the prophet and the sage, and the organizational structure of the Mishnah.

- The Introduction to Mishnah Sanhedrin, chapter ten (Perek Helek), is an eschatological essay that concludes with Maimonides's famous creed ("the thirteen principles of faith").

- The Introduction to Tractate Avot (popularly called The Eight Chapters) is an ethical treatise.

- Sefer Hamitzvot (trans. The Book of Commandments). In this work, Maimonides lists all the 613 mitzvot traditionally contained in the Torah (Pentateuch). He describes fourteen shorashim (roots or principles) to guide his selection.

- Sefer Ha'shamad (letter of Martydom)

- Mishneh Torah, a comprehensive code of Jewish law. It is also known as Yad ha-Chazaka or simply Yad/"יד" which has the numerical value 14, representing the 14 sections of the book.

- The Guide for the Perplexed, a philosophical work harmonising and differentiating Aristotle's philosophy and Jewish theology. Written in Judeo-Arabic, and completed between 1186 and 1190.[103] The first translation of this work into Hebrew was done by Samuel ibn Tibbon in 1204.[61]

- Teshuvot, collected correspondence and responsa, including a number of public letters (on resurrection and the afterlife, on conversion to other faiths, and Iggereth Teiman – addressed to the oppressed Jewry of Yemen).

- Hilkhot ha-Yerushalmi, a fragment of a commentary on the Jerusalem Talmud, identified and published by Saul Lieberman in 1947.

Medical works[edit]

Maimonides wrote ten known medical works in Arabic that have been translated by the Jewish medical ethicist Fred Rosner into contemporary English.[37][104]

- The Art of Cure – Extracts from Galen (Barzel, 1992, Vol. 5)[105] is essentially an extract of Galen's extensive writings.

- Commentary on the Aphorisms of Hippocrates (Rosner, 1987, Vol. 2; Hebrew:[106] פירוש לפרקי אבוקראט) is interspersed with his own views.

- Medical Aphorisms[107] of Moses (Rosner, 1989, Vol. 3) titled Fusul Musa in Arabic ("Chapters of Moses," Hebrew:[108] פרקי משה) contains 1500 aphorisms and many medical conditions are described.

- Treatise on Hemorrhoids (in Rosner, 1984, Vol. 1; Hebrew:[109] ברפואת הטחורים) discusses also digestion and food.

- Treatise on Cohabitation (in Rosner, 1984, Vol. 1) contains recipes as aphrodisiacs and anti-aphrodisiacs.

- Treatise on Asthma (Rosner, 1994, Vol. 6)[110] discusses climates and diets and their effect on asthma and emphasizes the need for clean air.

- Treatise on Poisons and Their Antidotes (in Rosner, 1984, Vol. 1) is an early toxicology textbook that remained popular for centuries.

- Regimen of Health (in Rosner, 1990, Vol. 4; Hebrew:[111] הנהגת הבריאות) is a discourse on healthy living and the mind-body connection.

- Discourse on the Explanation of Fits advocates healthy living and the avoidance of overabundance.

- Glossary of Drug Names (Rosner, 1992, Vol. 7)[112] represents a pharmacopeia with 405 paragraphs with the names of drugs in Arabic, Greek, Syrian, Persian, Berber, and Spanish.

Treatise on logic[edit]

The Treatise on Logic (Arabic: Maqala Fi-Sinat Al-Mantiq) has been printed 17 times, including editions in Latin (1527), German (1805, 1822, 1833, 1828), French (1935), and English (1938), and in an abridged Hebrew form. The work illustrates the essentials of Aristotelian logic to be found in the teachings of the great Islamic philosophers such as Avicenna and, above all, Al-Farabi, "the Second Master," the "First Master" being Aristotle. In his work devoted to the Treatise, Rémi Brague stresses the fact that Al-Farabi is the only philosopher mentioned therein. This indicates a line of conduct for the reader, who must read the text keeping in mind Al-Farabi's works on logic. In the Hebrew versions, the Treatise is called The words of Logic which describes the bulk of the work. The author explains the technical meaning of the words used by logicians. The Treatise duly inventories the terms used by the logician and indicates what they refer to. The work proceeds rationally through a lexicon of philosophical terms to a summary of higher philosophical topics, in 14 chapters corresponding to Maimonides's birthdate of 14 Nissan. The number 14 recurs in many of Maimonides's works. Each chapter offers a cluster of associated notions. The meaning of the words is explained and illustrated with examples. At the end of each chapter, the author carefully draws up the list of words studied.

Until very recently, it was accepted that Maimonides wrote the Treatise on logic in his twenties or even in his teen[113] years. Herbert Davidson has raised questions about Maimonides's authorship of this short work (and of other short works traditionally attributed to Maimonides). He maintains that Maimonides was not the author at all, based on a report of two Arabic-language manuscripts, unavailable to Western investigators in Asia Minor.[114] Rabbi Yosef Kafih maintained that it is by Maimonides and newly translated it to Hebrew (as Beiur M'lekhet HaHiggayon) from the Judeo-Arabic.[115]

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ "Moses Maimonides – Jewish philosopher, scholar, and physician".

- ^ "Hebrew Date Converter – 14th of Nisan, 4895 – Hebcal Jewish Calendar".

- ^ "Hebrew Date Converter – 14th of Nisan, 4898 – Hebcal Jewish Calendar".

- ^ Goldin, Hyman E. Kitzur Shulchan Aruch – Code of Jewish Law, Foreword to the New Edition. (New York: Hebrew Publishing Company, 1961)

- ^ "H-Net". Archived from the original on 2007-10-09. Retrieved 2007-05-06.

- ^ "The Influence of Islamic Thought on Maimonides". Maimonides Islamic Influences. Plato. Stanford. 2016.

- ^ "Isaac Newton: "Judaic monotheist of the school of Maimonides"". Achgut.com. 2007-06-19. Retrieved 2010-03-13.

- ^ Maimonides: Abū ʿImrān Mūsā [Moses] ibn ʿUbayd Allāh [Maymūn] al‐Qurṭubī www.islamsci.mcgill.ca

- ^ A Biographical and Historiographical Critique of Moses Maimonides Archived May 24, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ S. R. Simon (1999). "Moses Maimonides: medieval physician and scholar". Arch Intern Med. 159 (16): 1841–5. doi:10.1001/archinte.159.16.1841. PMID 10493314.

- ^ Athar Yawar Email Address (2008). "Maimonides's medicine". The Lancet. 371 (9615): 804. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60365-7.

- ^ Date of 1138 of the Common Era being the date of birth given by Maimonides himself, in the very last chapter and comment made by Maimonides in his Commentary of the Mishnah, Maimonides (1967), s.v. Uktzin 3:12 (end), and where he writes: "I began to write this composition when I was twenty-three years old, and I completed it in Egypt while I was aged thirty, which year is the 1,479th year of the Seleucid era (1168 CE)."

- ^ Joel E. Kramer, "Moses Maimonides: An Intellectual Portrait," p. 47 note 1. In Kenneth Seeskin, ed. (September 2005). The Cambridge Companion to Maimonides. ISBN 9780521525787.

- ^ 1138 in Stroumsa, Maimonides in His World: Portrait of a Mediterranean Thinker, Princeton University Press, 2009, p. 8

- ^ Sherwin B. Nuland (2008), Maimonides, Random House LLC, p. 38

- ^ "Moses Maimonides | biography – Jewish philosopher, scholar, and physician". Retrieved 2015-06-04.

- ^ Gedaliah ibn Yahya ben Joseph, Shalshelet Ha-Kabbalah Jerusalem 1962, p. ק; but in PDF p. 109 (Hebrew)

- ^ Abraham Zacuto, Sefer Yuchasin, Cracow 1580 (Hebrew), p. 261 in PDF, which reads: "… I saw in a booklet that the Ark of God, even Rabbi Moses b. Maimon, of blessed memory, had been taken up (i.e. euphemism for "had died"), in the year [4],965 anno mundi (= 1204/5 CE) in Egypt, and the Jews wept for him – as did [all] the Egyptians – three days, and they coined a name for that time of year, [saying], 'there was wailing,' and on the seventh day [of his passing], the news reached Alexandria, and on the eighth day, [the news reached] Jerusalem, and in Jerusalem they made a great public mourning [on his behalf] and called for a fast and public gathering, where it was that the prayer precentor read out the admonitions, 'If you shall walk in my statutes [etc.]' (Leviticus 26:3-ff.), as well as read the concluding verse [from the Prophets], 'And it came to pass that Samuel spoke to all of Israel [etc.],' and he then concluded by saying that the Ark of God had been taken away. Now after certain days they brought up his coffin to the Land of Israel, during which journey thieves encountered them, causing those who had gone up to flee, leaving there the coffin. Now the thieves, when they saw that they had all fled, they desired to have the coffin cast into the sea, but were unable with all their strength to uproot the coffin from the ground, even though they had been more than thirty men, and when they considered the matter, they then said to themselves that he was a godly and holy man, and so they went their way. However, they gave assurances to the Jews that they would escort them to their destination, and so it was that they also accompanied him and he was buried in Tiberias."

- ^ "Early Years". www.chabad.org. Retrieved 2020-05-21.

- ^ "Maimonides Ancestors". Retrieved 2020-05-21.

- ^ Stroumsa, Maimonides in His World: Portrait of a Mediterranean Thinker, Princeton University Press, 2009, p.65

- ^ Abraham Heschel, Maimonides (New York: Farrar Strauss, 1982), Chapter 15, "Meditation on God," pp. 157–162.

- ^ a b 1954 Encyclopedia Americana, vol. 18, p. 140.

- ^ Y. K. Stillman, ed. (1984). "Libās". Encyclopaedia of Islam. 5 (2nd ed.). Brill Academic Publishers. p. 744. ISBN 978-90-04-09419-2.

- ^ "Jewish Virtual Library". Jewish Virtual Library. Retrieved 2012-09-19.

- ^ Stroumsa (2009), Maimonides in His World, p.59

- ^ A.K. Bennison; M.A. Gallego García (2008). "Jewish Trading in Fez on the Eve of the Almohad Conquest" (PDF). Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - ^ Seder HaDoros (year 4927) quotes Maimonides as saying that he began writing his commentary on the Mishna when he was 23 years old, and published it when he was 30. Because of the dispute about the date of Maimonides's birth, it is not clear which year the work was published.

- ^ Davidson, p. 29.

- ^ a b Goitein, S.D. Letters of Medieval Jewish Traders, Princeton University Press, 1973 (ISBN 0-691-05212-3), p. 208

- ^ Magazine, rambam_temple_mount, Jewish. "No Jew had been permitted to enter the holy city which has become a Christian bastion since the Crusaders conquered it in 1096". www.jewishmag.com. Retrieved 2018-02-09.

- ^ Cohen, Mark R. Poverty and Charity in the Jewish Community of Medieval Egypt. Princeton University Press, 2005 (ISBN 0-691-09272-9), pp. 115–116

- ^ The "India Trade" (a term devised by the Arabist S.D. Goitein) was a highly lucrative business venture in which Jewish merchants from Egypt, the Mediterranean, and the Middle East imported and exported goods ranging from pepper to brass from various ports along the Malabar Coast between the 11th–13th centuries. For more info, see the "India Traders" chapter in Goitein, Letters of Medieval Jewish Traders, 1973 or Goitein, India Traders of the Middle Ages, 2008.

- ^ Goitein, Letters of Medieval Jewish Traders, p. 207

- ^ Cohen, Poverty and Charity in the Jewish Community of Medieval Egypt, p. 115

- ^ a b c Julia Bess Frank (1981). "Moses Maimonides: rabbi or medicine". The Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine. 54 (1): 79–88. PMC 2595894. PMID 7018097.

- ^ a b c Fred Rosner (2002). "The Life of Moses Maimonides, a Prominent Medieval Physician" (PDF). Einstein Quart J Biol Med. 19 (3): 125–128.

- ^ Gesundheit B, Or R, Gamliel C, Rosner F, Steinberg A (April 2008). "Treatment of depression by Maimonides (1138–1204): Rabbi, Physician, and Philosopher" (PDF). Am J Psychiatry. 165 (4): 425–428. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07101575. PMID 18381913. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-03-05.

- ^ Abraham Heschel, Maimonides (New York: Farrar Strauss, 1982), Chapter 15, "Meditation on God," pp. 157–162, and also pp. 178–180, 184–185, 204, etc. Isadore Twersky, editor, A Maimonides Reader (New York: Behrman House, 1972), commences his "Introduction" with the following remarks, p. 1: "Maimonides's biography immediately suggests a profound paradox. A philosopher by temperament and ideology, a zealous devotee of the contemplative life who eloquently portrayed and yearned for the serenity of solitude and the spiritual exuberance of meditation, he nevertheless led a relentlessly active life that regularly brought him to the brink of exhaustion."

- ^ Responsa Pe’er HaDor, 143.

- ^ Such views of his works are found in almost all scholarly studies of the man and his significance. See, for example, the "Introduction" sub-chapter by Howard Kreisel to his overview article "Moses Maimonides," in History of Jewish Philosophy, edited by Daniel H. Frank and Oliver Leaman, Second Edition (New York and London: Routledge, 2003), pp. 245–246.

- ^ Karo, Joseph (2002). David Avitan (ed.). Questions & Responsa Avqat Rokhel (in Hebrew). Jerusalem: Siyach Yisrael. p. 139 (responsum # 32). (first printed in Saloniki 1791)

- ^ Click to see full English translation of Maimonides's "Epistle to Yemen"

- ^ The comment on the effect of his "incessant travail" on his health is by Salo Baron, "Moses Maimonides," in Great Jewish Personalities in Ancient and Medieval Time, edited by Simon Noveck (B'nai B'rith Department of Adult Jewish Education, 1959), p. 227, where Baron also quotes from Maimonides's letter to Ibn Tibbon regarding his daily regime.

- ^ The Life of Maimonides jnul.huji.ac.il Archived 2010-11-20 at the Wayback Machine, Jewish National and University Library

- ^ hsje.org Amiram Barkat, "The End of the Exodus from Egypt" Archived 2011-07-17 at the Wayback Machine, Haaretz (Israel), 21 April 2005

- ^ אגרות הרמב"ם מהדורת שילת

- ^ Sarah E. Karesh; Mitchell M. Hurvitz (2005). Encyclopedia of Judaism. Facts on File. p. 305. ISBN 978-0-8160-5457-2.

- ^ H. J. Zimmels (1997). Ashkenazim and Sephardim: Their Relations, Differences, and Problems as Reflected in the Rabbinical Responsa (Revised ed.). Ktav Publishing House. p. 283. ISBN 978-0-88125-491-4.

- ^ Dogma in Medieval Jewish Thought, Menachem Kellner

- ^ "The Thirteen Principles of Jewish Faith". www.chabad.org.

- ^ See, for example: Marc B. Shapiro. The Limits of Orthodox Theology: Maimonides' Thirteen Principles Reappraised. Littman Library of Jewish Civilization (2011). pp. 1–14.

- ^ Siegelbaum, Chana Bracha (2010) Women at the crossroads : a woman's perspective on the weekly Torah portion Gush Etzion: Midreshet B'erot Bat Ayin. ISBN 9781936068098 page 199

- ^ Last section of Maimonides's Introduction to Mishneh Torah

- ^ "Avkat Rochel ch. 32".

- ^ Moses Maimonides, The Commandments, Neg. Comm. 290, at 269–71 (Charles B. Chavel trans., 1967).

- ^ Leslie, Donald. The Survival of the Chinese Jews; The Jewish Community of Kaifeng. Tʻoung pao, 10. Leiden: Brill, 1972, p. 157

- ^ Pollak, Michael. Mandarins, Jews, and Missionaries: The Jewish Experience in the Chinese Empire. The Jewish Publication Society of America, 1980, p. 413

- ^ Pollak, Mandarins, Jews, and Missionaries, pp. 297–298

- ^ "Hebrew Source of Maimonides's Levels of Giving with Danny Siegel's translation" (PDF). Retrieved 2012-09-19.

- ^ a b "The Guide to the Perplexed". World Digital Library. Retrieved 22 January 2013.

- ^ Kraemer, 326-8

- ^ Kraemer, 66

- ^ a b Robinson, George. "Maimonides’ Conception of God/" My Jewish Learning. 30 April 2018.

- ^ Telushkin, 29

- ^ Commentary on The Ethics of the Fathers 1:15. Qtd. in Telushkin, 115

- ^ Kraemer, 332-4

- ^ MT De'ot 6:1

- ^ "Maimonides believed that women were capable of being instructed in Talmud and even that women can be prophetesses." Kraemer, 336

- ^ Moses Maimonides (2007). The Guide to the Perplexed. BN Publishers.

- ^ Joseph Jacobs. "Moses Ben Maimon". Jewish Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2011-03-13.

- ^ Shlomo Pines (2006). "Maimonides (1135–1204)". Encyclopedia of Philosophy. 5: 647–654.

- ^ Isadore Twersky (2005). "Maimonides, Moses". Encyclopedia of Religion. 8: 5613–5618.

- ^ Joel E. Kramer, "Moses Maimonides: An Intellectual Portrait," p. 45. In Kenneth Seeskin, ed. (September 2005). The Cambridge Companion to Maimonides. ISBN 9780521525787.

- ^ Rudavsky, T. (March 2010). Maimonidies. Singapore: Wiley-Blackwell. p. 10. ISBN 978-1-4051-4898-6.

- ^ "Guide for the Perplexed, on". Sacred-texts.com. Retrieved 2010-03-13.

- ^ See: Maimonides's Ma'amar Teḥayyath Hamethim (Treatise on the Resurrection of the Dead), published in Book of Letters and Responsa (ספר אגרות ותשובות), Jerusalem 1978, p. 9 (Hebrew). According to Maimonides, certain Jews in Yemen had sent to him a letter in the year 1189, evidently irritated as to why he had not mentioned the physical resurrection of the dead in his Hil. Teshuvah, chapter 8, and how that some persons in Yemen had begun to instruct, based on Maimonides's teaching, that when the body dies it will disintegrate and the soul will never return to such bodies after death. Maimonides denied that he ever insinuated such things, and reiterated that the body would indeed resurrect, but that the "world to come" was something different in nature.

- ^ Kraemer, 422

- ^ Commentary on the Mishna, Avot 5:6

- ^ Within [the Torah] there is also another part which is called ‘hidden’ (mutsnaʿ), and this [concerns] the secrets (sodot) which the human intellect cannot attain, like the meanings of the statutes (ḥukim) and other hidden secrets. They can neither be attained through the intellect nor through sheer volition, but they are revealed before Him who created [the Torah] (Rabbi Abraham ben Asher, The Or ha-Sekhel)

- ^ Such as the first (religious) criticism of Kabbalah, Ari Nohem, by Leon Modena from 1639. In it, Modena urges a return to Maimonidean Aristotelianism. The Scandal of Kabbalah: Leon Modena, Jewish Mysticism, Early Modern Venice, Yaacob Dweck, Princeton University Press, 2011.

- ^ Menachem Kellner, Maimonides' Confrontation With Mysticism, Littman Library, 2006

- ^ Maimonides: Philosopher and Mystic from Chabad.org

- ^ Contemporary academic views in the study of Jewish mysticism, hold that 12-13th century Kabbalists wrote down and systemised their transmitted oral doctrines in oppositional response to Maimonidean rationalism. See e.g. Moshe Idel, Kabbalah: New Perspectives

- ^ The first comprehensive systemiser of Kabbalah, Moses ben Jacob Cordovero, for example, was influenced by Maimonides. One example is his instruction to undercut any conception of a Kabbalistic idea after grasping it in the mind. One's intellect runs to God in learning the idea, then returns back in qualified rejection of false spatial/temporal conceptions of the idea's truth, as the human mind can only think in material references. Cited in Louis Jacobs, The Jewish Religion: A Companion, Oxford University Press, 1995, entry on Cordovero

- ^ Norman Lamm, The Religious Thought of Hasidism: Text and Commentary, Ktav Pub, 1999: Introduction to chapter on Faith/Reason has historical overview of religious reasons for opposition to Jewish philosophy, including the Ontological reason, one Medieval Kabbalist holding that "we begin where they end"

- ^ "Oath and Prayer of Maimonides". Library.dal.ca. Archived from the original on 2008-06-29. Retrieved 2010-03-13.

- ^ Friedländer, Michael. Guide for the Perplexed. Dover Publications. ISBN 9780486203515.

- ^ Maimonides, Moses, 1135-1204 (1974-12-15). The guide of the perplexed. Pines, Shlomo, 1908-1990,, Strauss, Leo, Bollingen Foundation Collection (Library of Congress). [Chicago]. ISBN 0226502309. OCLC 309924.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ^ Isidore Twersky, Introduction to the Code of Maimonides (Mishneh Torah), Yale Judaica Series, vol. XII (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1980). passim, and especially Chapter VII, "Epilogue," pp. 515–538.

- ^ This is covered in all histories of the Jews. E.g., including such a brief overview as Cecil Roth, A History of the Jews, Revised Edition (New York: Schocken, 1970), pp. 175–179.

- ^ D.J. Silver, Maimonidean Criticism and the Maimonidean Controversy, 1180–1240 (Leiden: Brill, 1965), is still the most detailed account.

- ^ David Hartman, Maimonides: Torah and Philosophic Quest (Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society of America, 1976), p. 98.

- ^ On the extensive philosophical aspects of Maimonides's halakhic works, see in particular Isidore Twersky's Introduction to the Code of Maimonides (Mishneh Torah), Yale Judaica Series, vol. XII (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1980). Twersky devotes a major portion of this authoritative study to the philosophical aspects of the Mishneh Torah itself.

- ^ The Maimunist or Maimonidean controversy is covered in all histories of Jewish philosophy and general histories of the Jews. For an overview, with bibliographic references, see Idit Dobbs-Weinstein, "The Maimonidean Controversy," in History of Jewish Philosophy, Second Edition, edited by Daniel H. Frank and Oliver Leaman (London and New York: Routledge, 2003), pp. 331–349. Also see Colette Sirat, A History of Jewish Philosophy in the Middle Ages (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1985), pp. 205–272.

- ^ Mercedes Rubio (2006). "Aquinas and Maimonides on the Divine Names". Aquinas and Maimonides on the possibility of the knowledge of god. Springer-Verlag. pp. 65–126. doi:10.1007/1-4020-4747-9_2. ISBN 978-1-4020-4720-6.

- ^ Vivian McAlister, Maimonides's cooling period and organ retrieval (Canadian Journal of Surgery 2004; 47: 8 – 9)

- ^ "Maimonides – His Thought Related to Ecology in The Encyclopedia of Religion and Nature".

- ^ David Morris. "Major Grant Awarded to Maimonides". Florida Jewish Journal. Archived from the original on July 30, 2007. Retrieved 2010-03-13.

- ^ "Harvard University Press: Maimonides after 800 Years : Essays on Maimonides and his Influence by Jay M. Harris". Hup.harvard.edu. Retrieved 2010-03-13.

- ^ Shelly Paz (8 May 2008) Tourism Ministry plans joint project with Morocco, Spain. The Jerusalem Post

- ^ "The Israel Museum, Jerusalem". www.imj.org.il. Retrieved 2019-07-11.

- ^ Kehot Publication Society, Chabad.org.

- ^ Volume 5 translated by Barzel (foreword by Rosner).

- ^ Title page, TOC.

- ^ "כתבים רפואיים – ג (פירוש לפרקי אבוקראט) / משה בן מימון (רמב"ם) / ת"ש-תש"ב – אוצר החכמה".

- ^ Maimonides. Medical Aphorisms (Treatises 1–5 6–9 10–15 16–21 22–25), Brigham Young University, Provo – Utah

- ^ "כתבים רפואיים – ב (פרקי משה ברפואה) / משה בן מימון (רמב"ם) / ת"ש-תש"ב – אוצר החכמה".

- ^ "כתבים רפואיים – ד (ברפואת הטחורים) / משה בן מימון (רמב"ם) / ת"ש-תש"ב – אוצר החכמה".

- ^ Title page, TOC.

- ^ "כתבים רפואיים – א (הנהגת הבריאות) / משה בן מימון (רמב"ם) / ת"ש-תש"ב – אוצר החכמה".

- ^ Title page, TOC.

- ^ Abraham Heschel, Maimonides. New York: Farrar Strauss, 1982 p. 22 ("at sixteen")

- ^ Davidson, pp. 313 ff.

- ^ "באור מלאכת ההגיון / משה בן מימון (רמב"ם) / תשנ"ז – אוצר החכמה".

See also[edit]

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Joseph Jacobs, Isaac Broydé, The Executive Committee of the Editorial Board, and Jacob Zallel Lauterbach (1901–1906). "Moses Ben Maimon". In Singer, Isidore; et al. (eds.). The Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk & Wagnalls.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Joseph Jacobs, Isaac Broydé, The Executive Committee of the Editorial Board, and Jacob Zallel Lauterbach (1901–1906). "Moses Ben Maimon". In Singer, Isidore; et al. (eds.). The Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk & Wagnalls.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

Bibliography[edit]

- Barzel, Uriel (1992). Maimonides's Medical Writings: The Art of Cure Extracts. 5. Galen: Maimonides Research Institute.

- Bos, Gerrit (2002). Maimonides. On Asthma (vol.1, vol.2). Provo, Utah: Brigham Young University Press.

- Bos, Gerrit (2007). Maimonides. Medical Aphorisms Treatise 1–5 (6–9, 10–15, 16–21, 22–25). Provo, Utah: Brigham Young University Press.

- Davidson, Herbert A. (2005). Moses Maimonides: The Man and his Works. Oxford University Press.

- Feldman, Rabbi Yaakov (2008). Shemonah Perakim: The Eight Chapters of the Rambam. Targum Press.

- Fox, Marvin (1990). Interpreting Maimonides. Univ. of Chicago Press.

- Guttman, Julius (1964). David Silverman (ed.). Philosophies of Judaism. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society of America.

- Halbertal, Moshe (2013). Maimonides: Life and Thought. Princeton University Press.

- Hart Green, Kenneth (2013). Leo Strauss on Maimonides: The Complete Writings. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Hartman, David (1976). Maimonides: Torah and Philosophic Quest. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society of America.

- Heschel, Abraham Joshua (1982). Maimonides: The Life and Times of a Medieval Jewish Thinker. New York: Farrar Strauss.

- Husik, Isaac (2002) [1941]. A History of Jewish Philosophy. Dover Publications, Inc. Originally published by the Jewish Publication of America, Philadelphia.

- Kaplan, Aryeh (1994). "Maimonides Principles: The Fundamentals of Jewish Faith". The Aryeh Kaplan Anthology. I.

- Kellner, Menachem (1986). Dogma in Medieval Jewish Thought. London: Oxford University press.

- Kohler, George Y. (2012). "Reading Maimonides's Philosophy in 19th Century Germany". Amsterdam Studies in Jewish Philosophy. 15.

- Kraemer, Joel L. (2008). Maimonides: The Life and World of One of Civilization's Greatest Minds. Doubleday.

- Leaman, Daniel H.; Leaman, Frank; Leaman, Oliver (2003). History of Jewish Philosophy (Second ed.). London and New York: Routledge. See especially chapters 10 through 15.

- Maimonides (1967). Mishnah, with Maimonides' Commentary (in Hebrew). 3. Translated by Yosef Qafih. Jerusalem: Mossad Harav Kook. OCLC 741081810.

- Rosner, Fred (1984–1994). Maimonides's Medical Writings. 7 Vols. Maimonides Research Institute. (Volume 5 translated by Uriel Barzel; foreword by Fred Rosner.)

- Seidenberg, David (2005). "Maimonides – His Thought Related to Ecology". The Encyclopedia of Religion and Nature.

- Shapiro, Marc B. (1993). "Maimonides Thirteen Principles: The Last Word in Jewish Theology?". The Torah U-Maddah Journal. 4.

- Shapiro, Marc B. (2008). Studies in Maimonides and His Interpreters. Scranton (PA): University of Scranton Press.

- Sirat, Colette (1985). A History of Jewish Philosophy in the Middle Ages. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. See chapters 5 through 8.

- Strauss, Leo (1974). Shlomo Pines (ed.). How to Begin to Study the Guide: The Guide of the Perplexed – Maimonides (in Arabic). 1. University of Chicago Press.

- Strauss, Leo (1988). Persecution and the Art of Writing. University of Chicago Press. reprint

- Stroumsa, Sarah (2009). Maimonides in His World: Portrait of a Mediterranean Thinker. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-13763-6.

- Telushkin, Joseph (2006). A Code of Jewish Ethics. 1 (You Shall Be Holy). New York: Bell Tower. OCLC 460444264.

- Twersky, Isadore (1972). I Twersky (ed.). A Maimonides Reader. New York: Behrman House.

- Twersky, Isador (1980). "Introduction to the Code of Maimonides (Mishneh Torah". Yale Judaica Series. New Haven and London. XII.

External links[edit]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Moshe ben Maimon. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Maimonides |

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: Moshe ben Maimon |

- About Maimonides

- Video lecture on Maimonides by Dr. Henry Abramson

- Maimonides entry in Jewish Encyclopedia

- Maimonides entry in the Encyclopædia Britannica

- Maimonides entry in the Encyclopaedia Judaica, 2nd edition

- Seeskin, Kenneth. "Maimonides". In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- "Maimonides entry in the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy"

- Maimonides, a biography — book by David Yellin and Israel Abrahams

- Maimonides as a Philosopher

- The Influence of Islamic Thought on Maimonides

- "The Moses of Cairo," Article from Policy Review

- Rambam and the Earth: Maimonides as a Proto-Ecological Thinker – reprint on neohasid.org from The Encyclopedia of Religion and Ecology

- Anti-Maimonidean Demons by Jose Faur, describing the controversy surrounding Maimonides's works

- David Yellin and Israel Abrahams, Maimonides (1903) (full text of a biography)

- Y. Tzvi Langermann (2007). "Maimonides: Abū ʿImrān Mūsā [Moses] ibn ʿUbayd Allāh [Maymūn] al‐Qurṭubī". In Thomas Hockey; et al. (eds.). The Biographical Encyclopedia of Astronomers. New York: Springer. pp. 726–7. ISBN 978-0-387-31022-0. (PDF version)

- Maimonides at intellectualencounters.org

- Kriesel, Howard (2015). Judaism as Philosophy: Studies in Maimonides and the Medieval Jewish Philosophers of Provence. Boston: Academic Studies Press. doi:10.2307/j.ctt21h4xpc. ISBN 9781618117892. JSTOR j.ctt21h4xpc.

- Friedberg, Albert (2013). Crafting the 613 Commandments: Maimonides on the Enumeration, Classification, and Formulation of the Scriptural Commandments. Boston: Academic Studies Press. doi:10.2307/j.ctt21h4wf8. ISBN 9781618118486. JSTOR j.ctt21h4wf8.

- Yahoo Maimonides Discussion Group

- The Guide: An Explanatory Commentary on Each Chapter of Maimonides' Guide of The Perplexed by Scott Michael Alexander (covers all of Book I, currently)

- Maimonides's works

- Complete Mishneh Torah online, halakhic work of Maimonides

- Sefer Hamitzvot, English translation

- Oral Readings of Mishne Torah — Free listening and Download, site also had classes in Maimonides's Iggereth Teiman

- Maimonides 13 Principles

- Intellectual Encounters – Main Thinkers – Moses Maimonides, in intellectualencounters.org

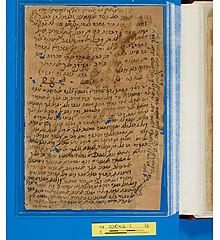

- Maimonides, Mishneh Torah, Autograph Draft, Egypt, c. 1180

- Maimonides, Commentary on the Mishnah, Autograph Manuscript, Egypt, c. 1167–68

- Texts by Maimonides

- Siddur Mesorath Moshe, a prayerbook based on the early Jewish liturgy as found in Maimonides's Mishne Tora

- Rambam's introduction to the Mishneh Torah (English translation)

- Rambam's introduction to the Commentary on the Mishnah (Hebrew language|Hebrew Fulltext)

- The Guide For the Perplexed by Moses Maimonides translated into English by Michael Friedländer

- Writings of Maimonides; manuscripts and early print editions. Jewish National and University Library

- Facsimile edition of Moreh Nevukhim/The Guide for the Perplexed (illuminated Hebrew manuscript, Barcelona, 1347–48). The Royal Library, Copenhagen

- University of Cambridge Library collection of Judeo-Arabic letters and manuscripts written by or to Maimonides. It includes the last letter his brother David sent him before drowning at sea.

- A. Ashur, A newly discovered medical recipe written by Maimonides

- M.A Friedman and A. Ashur, A newly-discovered autograph responsum of Maimonides

- Works by Maimonides at Post-Reformation Digital Library

|

- Maimonides

- 1138 births

- 1204 deaths

- People from Córdoba, Spain

- Medieval Jewish physicians of Spain

- Medieval Jewish physicians of Egypt

- Physicians of medieval Islam

- Aristotelian philosophers

- Philosophers of Judaism

- Sephardi rabbis

- Egyptian rabbis

- Spanish rabbis

- Spanish refugees

- Jewish refugees

- 12th-century rabbis

- 13th-century rabbis

- Rishonim

- 12th-century Jewish theologians

- 12th-century physicians

- Court physicians

- 12th-century philosophers

- 13th-century philosophers

- University of al-Qarawiyyin alumni

- Medieval Jewish astronomers

- Jewish astronomers

- Exponents of Jewish law

- Commentaries on the Mishnah

- 12th-century Arabic writers

- 12th-century Al-Andalus people

- Judeo-Arabic writers

- Jewish ethicists

- Philosophers of Al-Andalus