Nintendo

Logo used since 2016 | |

Nintendo's headquarters in Kyoto | |

Native name | 任天堂株式会社 |

|---|---|

Romanized name | Nintendō Kabushiki-gaisha |

Formerly |

|

| Public | |

| Traded as | TYO: 7974 NASDAQ: NTDOY NASDAQ: NTDOF FWB: NTO |

| ISIN | JP3756600007 |

| Industry | |

| Founded | 23 September 1889 |

| Founder | Fusajiro Yamauchi |

| Headquarters | , Japan |

Area served | Worldwide |

Key people | |

| Products | |

Production output |

|

| Services | |

| Revenue | |

| Total assets | |

| Total equity | |

Number of employees | Nintendo Co., Ltd 2,395 Nintendo (total) 6,200[2] (2020) |

| Divisions |

|

| Subsidiaries | |

| Website | nintendo.com |

Nintendo Co., Ltd.[a] is a Japanese consumer electronics and video game company headquartered in Kyoto. Its international branches, Nintendo of America and Nintendo of Europe, are respectively headquartered in Redmond, Washington, and Frankfurt, Germany. Nintendo is one of the world's largest video game companies by market capitalization, creating some of the best-known and top-selling video game franchises of all-time, such as Mario, The Legend of Zelda, Animal Crossing, and Pokémon.

Nintendo was founded by Fusajiro Yamauchi on 23 September 1889 and originally produced handmade hanafuda playing cards. By 1963, the company had tried several small niche businesses, such as cab services and love hotels, without major success. Abandoning previous ventures in favor of toys in the 1960s, Nintendo developed into a video game company in the 1970s. Supplemented since the 1980s by its regional branches Nintendo of America and Nintendo of Europe, it ultimately became one of the most influential in the video game industry and one of Japan's most-valuable companies, with a market value of over US$37 billion by 2018.[3]

History

This section may be too long and excessively detailed. (February 2020) |

1889–1956: As a card company

Nintendo was founded as a playing card company by Fusajiro Yamauchi on 23 September 1889.[4] Based in Kyoto, the business produced and marketed hanafuda cards. The handmade cards soon became popular, and Yamauchi hired assistants to mass-produce cards to satisfy demand.[5] The company was formally established as an unlimited partnership titled Yamauchi Nintendo & Co. Ltd. in 1933.[6] It changed its name to Nintendo Playing Card Co. Ltd. in 1951.[6] Nintendo continues to manufacture playing cards in Japan and organizes its own contract bridge tournament called the "Nintendo Cup".[7][8] The word Nintendo can be translated as "leave luck to heaven", or alternatively as "the temple of free hanafuda".[9][10]

1956–1974: New ventures

In 1963, Yamauchi renamed Nintendo Playing Card Co. Ltd. to Nintendo Co., Ltd.[6] The company then began to experiment in other areas of business using newly injected capital during the period of time between 1963 and 1968. Nintendo set up a taxi company called Daiya. This business was initially successful. However, Nintendo was forced to sell it because problems with the labor unions were making it too expensive to run the service. It also set up a love hotel chain, a TV network, a food company (selling instant rice) and several other ventures.[11] All of these ventures eventually failed, and after the 1964 Tokyo Olympics, playing card sales dropped, and Nintendo's stock price plummeted to its lowest recorded level of ¥60.[12][13]

In 1966, Nintendo moved into the Japanese toy industry with the Ultra Hand, an extendable arm developed by its maintenance engineer Gunpei Yokoi in his free time. Yokoi was moved from maintenance to the new "Nintendo Games" department as a product developer. Nintendo continued to produce popular toys, including the Ultra Machine, Love Tester and the Kousenjuu series of light gun games.[citation needed] Despite some successful products, Nintendo struggled to meet the fast development and manufacturing turnaround required in the toy market, and fell behind the well-established companies such as Bandai and Tomy.[5] In 1973, its focus shifted to family entertainment venues with the Laser Clay Shooting System, using the same light gun technology used in Nintendo's Kousenjuu series of toys, and set up in abandoned bowling alleys. Following some success, Nintendo developed several more light gun machines (such as the light gun shooter game Wild Gunman) for the emerging arcade scene. While the Laser Clay Shooting System ranges had to be shut down following excessive costs, Nintendo had found a new market.

1974–1978: Early electronic era

Nintendo's first venture into the video game industry was securing rights to distribute the Magnavox Odyssey video game console in Japan in 1974. Nintendo began to produce its own hardware in 1977, with the Color TV-Game home video game consoles.

A student product developer named Shigeru Miyamoto was hired by Nintendo at this time.[14] He worked for Yokoi, and one of his first tasks was to design the casing for several of the Color TV-Game consoles. Miyamoto went on to create, direct and produce some of Nintendo's most famous video games and become one of the most recognizable figures in the video game industry.[14]

In 1975, Nintendo moved into the video arcade game industry with EVR Race, designed by their first game designer, Genyo Takeda,[15] and several more games followed. Nintendo had some small success with this venture, but the release of Donkey Kong in 1981, designed by Miyamoto, changed Nintendo's fortunes dramatically. The success of the game and many licensing opportunities (such as ports on the Atari 2600, Intellivision and ColecoVision) gave Nintendo a huge boost in profit and in addition, the game also introduced an early iteration of Mario, then known in Japan as Jumpman, the eventual company mascot. Nintendo would continue to manufacture arcade games and systems until 1992.[16][17]

1979–1982: First video game success

In 1979, Gunpei Yokoi conceived the idea of a handheld video game, while observing a fellow bullet train commuter who passed the time by interacting idly with a portable LCD calculator. The idea became Game & Watch.[18] In 1980, Nintendo launched Game & Watch—a handheld video game series developed by Yokoi. These systems do not contain interchangeable cartridges and thus the hardware was tied to the game. The first Game & Watch game, Ball, was distributed worldwide. The modern "cross" D-pad design was developed in 1982, by Yokoi for a Donkey Kong version. Proven to be popular, the design was patented by Nintendo. It later earned a Technology & Engineering Emmy Award.[19][20]

1983–1989: Nintendo Entertainment System and Game Boy

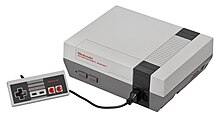

In 1983, Nintendo launched the Family Computer (colloquialized as "Famicom") home video game console in Japan, alongside ports of its most popular arcade games. In 1985, a cosmetically reworked version of the system known outside Japan as the Nintendo Entertainment System, or NES, launched in North America. The practice of bundling the system along with select games helped to make Super Mario Bros. one of the best-selling video games in history.[21]

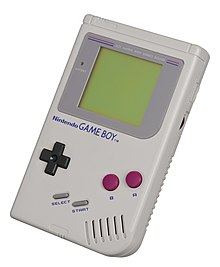

In 1988, Gunpei Yokoi and his team at Nintendo R&D1 conceived the new Game Boy handheld system, with the purpose of merging the two very successful ideas of the Game & Watch's portability along with the NES's cartridge interchangeability. Nintendo released the Game Boy in Japan on 21 April 1989, and in North America on 31 July 1989. Nintendo of America president Minoru Arakawa managed a deal to bundle the popular third-party game Tetris along with the Game Boy, and the pair launched as an instant success.

1989–1995: Super Nintendo Entertainment System and Virtual Boy

In 1989, Nintendo announced plans to release the successor to the Famicom, the Super Famicom. Based on a 16-bit processor, Nintendo boasted significantly superior hardware specifications of graphics, sound, and game speed over the original 8-bit Famicom. The Super Famicom was finally released relatively late to the market in Japan on 21 November 1990, and released as the Super Nintendo Entertainment System (officially abbreviated the Super NES or SNES and commonly shortened to Super Nintendo) in North America on 23 August 1991 and in Europe in 1992. Its main rival was the 16-bit Mega Drive, known in North America as Genesis, which had been advertised aggressively against the nascent 8-bit NES. A console war between Sega and Nintendo ensued during the early 1990s.[22] From 1990 to 1992, Nintendo opened World of Nintendo shops in the United States where consumers could test and buy Nintendo products.

In August 1993, Nintendo announced the SNES's successor, codenamed Project Reality. Featuring 64-bit graphics, the new system was developed as a joint venture between Nintendo and North-American-based technology company Silicon Graphics. The system was announced to be released by the end of 1995, but was subsequently delayed. Meanwhile, Nintendo continued the Nintendo Entertainment System family with the release of the NES-101, a smaller redesign of the original NES. Nintendo also announced a CD drive peripheral called the Super NES CD-ROM Adapter, which was co-developed first by Sony with the name "Play Station" and then by Philips. Bearing prototypes and joint announcements at the Consumer Electronics Show, it was on track for a 1994 release, but was controversially canceled.

In 1995, Nintendo announced that it had sold one billion game cartridges worldwide,[23][24] ten percent of those being from the Mario franchise.[citation needed] Nintendo deemed 1994 the "Year of the Cartridge". To further their support for cartridges, Nintendo announced that Project Reality, which had now been renamed the Ultra 64, would not use a CD format as expected, but would rather use cartridges as its primary media format. Nintendo IRD general manager Genyo Takeda was impressed by video game development company Rare's progress with real-time 3D graphics technology, using state of the art Silicon Graphics workstations. As a result, Nintendo bought a 25% stake in the company, eventually expanding to 49%, and offered their catalog of characters to create a CGI game around, making Rare Nintendo's first western-based second-party developer.[25] Their first game as partners with Nintendo was Donkey Kong Country. The game was a critical success and sold over eight million copies worldwide, making it the second best-selling game in the SNES library.[25] In September 1994, Nintendo, along with six other video game giants including Sega, Electronic Arts, Atari, Acclaim, Philips, and 3DO approached the United States Senate and demanded a ratings system for video games to be enforced, which prompted the decision to create the Entertainment Software Rating Board.

Aiming to produce an affordable virtual reality console, Nintendo released the Virtual Boy in 1995, designed by Gunpei Yokoi. The console consists of a head-mounted semi-portable system with one red-colored screen for each of the user's eyes, featuring stereoscopic graphics. Games are viewed through a binocular eyepiece and controlled using an affixed gamepad. Critics were generally disappointed with the quality of the games and the red-colored graphics, and complained of gameplay-induced headaches.[26] The system sold poorly and was quietly discontinued.[27] Amid the system's failure, Yokoi retired from Nintendo.[28] During the same year, Nintendo launched the Satellaview in Japan, a peripheral for the Super Famicom. The accessory allowed users to play video games via broadcast for a set period of time. Various games were made exclusively for the platform, as well as various remakes.

1996–2000: Nintendo 64 and Game Boy Color

In 1996, Nintendo renamed the Ultra 64 to Nintendo 64, releasing it in Japan and North America, and in 1997 in Europe and Australia. The Nintendo 64 continued what had become a Nintendo tradition of hardware design which is focused less on high performance specifications than on design innovations intended to inspire game development.[29] With its market shares slipping to the Sega Saturn and partner-turned-rival Sony PlayStation, Nintendo revitalized its brand by launching a $185 million marketing campaign centered around the "Play it Loud" slogan.[30] During the same year, Nintendo also released the Game Boy Pocket in Japan, a smaller version of the Game Boy that generated more sales for the platform. On 4 October 1997, famed Nintendo developer Gunpei Yokoi died in a car crash. In 1997, Nintendo released the SNS-101 (called Super Famicom Jr. in Japan), a smaller redesigned version of the Super Nintendo Entertainment System.

In 1998, the successor to the Game Boy, the Game Boy Color, was released. The system had improved technical specifications allowing it to run games made specifically for the system as well as games released for the Game Boy, albeit with added color. The Game Boy Camera and Printer were also released as accessories. In October 1998, Retro Studios was founded as an alliance between Nintendo and former Iguana Entertainment founder Jeff Spangenberg. Nintendo saw an opportunity for the new studio to create games for the upcoming GameCube targeting an older demographic, in the same vein as Iguana Entertainment's successful Turok series for the Nintendo 64.[31]

2001–2003 Game Boy Advance and GameCube

In 2001, Nintendo introduced the redesigned Game Boy Advance. The same year, Nintendo also released the GameCube to lukewarm sales, and it ultimately failed to regain the market share lost by the Nintendo 64. When Yamauchi, company president since 1949, retired on 24 May 2002,[32][33] Satoru Iwata became first Nintendo president who was unrelated to the Yamauchi family through blood or marriage since its founding in 1889.[34][35]

In 2003, Nintendo released the Game Boy Advance SP, a redesign of the Game Boy Advance that featured a clamshell design that would later be used in Nintendo's DS and 3DS handheld video game systems.

2004–2011: Nintendo DS and Wii

In 2004, Nintendo released the Nintendo DS, its fourth major handheld system. The DS is a dual screened handheld featuring touch screen capabilities, which respond to either a stylus or the touch of a finger. Former Nintendo president and chairman Hiroshi Yamauchi was translated by GameScience as explaining, "If we can increase the scope of the industry, we can re-energise the global market and lift Japan out of depression – that is Nintendo's mission." Regarding lukewarm GameCube sales which had yielded the company's first reported operating loss in over 100 years, Yamauchi continued: "The DS represents a critical moment for Nintendo's success over the next two years. If it succeeds, we rise to the heavens, if it fails, we sink into hell."[36][37][38] Due to games such as Nintendogs and Mario Kart DS, the DS became a success. In 2005, Nintendo released the Game Boy Micro in North America, a redesign of the Game Boy Advance. The last system in the Game Boy line, it is also the smallest Game Boy, and the least successful. In the middle of 2005, Nintendo opened the Nintendo World Store in New York City, which would sell Nintendo games, present a museum of Nintendo history, and host public parties such as for product launches. The store was renovated and renamed as Nintendo New York in 2016.

In the first half of 2006, Nintendo released the Nintendo DS Lite, a version of the original Nintendo DS with lighter weight, brighter screen, and better battery life. In addition to this streamlined design, its prolific subset of casual games appealed to the masses, such as the Brain Age series. Meanwhile, New Super Mario Bros. provided a substantial addition to the Mario series when it was launched to the top of sales charts. The successful direction of the Nintendo DS had a big influence on Nintendo's next home console (including the common Nintendo Wi-Fi Connection),[39] which had been codenamed "Revolution" and was now renamed to "Wii".[citation needed] In August 2006, Nintendo published ES, a now-dormant, open source research operating system project designed around web application integration but for no specific purpose.[40][41]

In the latter half of 2006, Nintendo released the Wii as the backward-compatible successor to the GameCube. Based upon intricate Wii Remote motion controls and a balance board, the Wii inspired several new game franchises, some targeted at entirely new market segments of casual and fitness gaming. With more than 100 million units sold worldwide, the Wii is the best selling console of the seventh generation, regaining market share lost during the tenures of the Nintendo 64 and GameCube.

On 1 May 2007, Nintendo acquired an 80% stake in video game development company Monolith Soft, previously owned by Bandai Namco. Monolith Soft is best known for developing role-playing games such as the Xenosaga, Baten Kaitos, and Xenoblade series.[42]

During the holiday season of 2008, Nintendo followed up the success of the DS with the release of the Nintendo DSi in Japan. The system features a more powerful CPU and more RAM, two cameras, one facing towards the player and one facing outwards, and had an online distribution store called DSiWare. The DSi was later released worldwide during 2009. In the latter half of 2009, Nintendo released the Nintendo DSi XL in Japan, a larger version of the DSi. This system was later released worldwide in 2010.

2011–2015: Nintendo 3DS and Wii U

In 2011, Nintendo released the Nintendo 3DS, based upon a glasses-free stereoscopic 3D display. In February 2012, Nintendo acquired Mobiclip, a France-based research and development company specialized in highly optimized software technologies such as video compression. The company's name was later changed to Nintendo European Research & Development.[43] During the fourth quarter of 2012, Nintendo released the Wii U. It sold slower than expected,[44][45] despite being the first eighth generation console. By September 2013, however, sales had rebounded.[clarification needed] Intending to broaden the 3DS market, Nintendo released 2013's cost-reduced Nintendo 2DS. The 2DS is compatible with but lacks the 3DS's more expensive but cosmetic autostereoscopic 3D feature. Nintendo also released the Wii Mini, a cheaper and non-networked redesign of the Wii.[46]

On 25 September 2013, Nintendo announced it had purchased a 28% stake in a Panasonic spin-off company called PUX Corporation. The company specializes in face and voice recognition technology, with which Nintendo intends to improve the usability of future game systems. Nintendo has also worked with this company in the past to create character recognition software for a Nintendo DS touchscreen.[47] After announcing a 30% dive in profits for the April to December 2013 period, president Satoru Iwata announced he would take a 50% pay-cut,[48] with other executives seeing reductions by 20%–30%.[49]

In January 2015, Nintendo announced its exit from the Brazilian market after four years of distributing products in the country. Nintendo cited high import duties and lack of local manufacturing operation as reasons for leaving. Nintendo continues its partnership with Juegos de Video Latinoamérica to distribute products to the rest of Latin America.[50]

On 11 July 2015, Iwata died from a bile duct tumor at the age of 55. Following his death, representative directors Genyo Takeda and Shigeru Miyamoto jointly led the company on an interim basis until the appointment of Tatsumi Kimishima as Iwata's successor on 16 September 2015.[51] In addition to Kimishima's appointment, the company's management organization was also restructured—Miyamoto was named "Creative Fellow" and Takeda was named "Technology Fellow".[52]

2015–present: Mobile and Nintendo Switch

On 17 March 2015, Nintendo announced a partnership with Japanese mobile developer DeNA to produce games for smart devices.[53][54] The first of these, Miitomo, was released in March 2016.[55]

On the same day, Nintendo announced a new "dedicated games platform with a brand new concept" with the codename "NX" that would be further revealed in 2016.[54][56] Reggie Fils-Aimé, president of Nintendo of America, referred to NX as "our next home console" in a June 2015 interview with The Wall Street Journal.[57] In a later article from October 2015, The Wall Street Journal relayed speculation from unnamed inside sources that the NX was intended to feature "industry leading" hardware specifications and be usable as both a home and portable console. It was also reported that Nintendo had begun distributing software development kits (SDKs) for it to third-party developers, with the unnamed source further speculating that these moves suggested that the company was on track to introduce it as early as 2016.[58] At an investor's meeting on 27 April 2016, Nintendo announced that the NX would be released worldwide in March 2017.[59] In an interview with Asahi Shimbun in May 2016, Kimishima stated that the NX was a new concept that would not succeed the 3DS or Wii U product lines.[60] At a shareholders' meeting following E3 2016, Shigeru Miyamoto stated that the company chose not to present the NX during the conference due to concerns that competitors could copy from it if they revealed it too soon.[61] The same day, Kimishima also revealed during a Q&A session with investors that they were also researching virtual reality.[62]

In May 2015, Universal Parks & Resorts announced that it was partnering with Nintendo to create attractions at Universal theme parks based upon Nintendo properties.[63] In May 2016, Nintendo also expressed a desire to enter the animated film market.[64] In November 2016, it was stated that the area to be created at Universal theme parks is known as Super Nintendo World, which will be completed by 2020 at Universal Studios Japan in time of the 2020 Tokyo Olympics, whereas Universal Orlando Resort and Universal Studios Hollywood will get the themed area in an unspecified date after the Japanese version.[65]

In June 2015, Nintendo discontinued the basic Wii U model in Japan, and replaced by a 32 GB "Premium" set, that includes white hardware and a Wii Remote Plus[66][67]

In July 2016, the company announced it was bringing back the NES in the form of the NES Classic Edition (called Nintendo Classic Mini in Europe). The plug-and-play console supports HDMI, two-player mode, and has a controller similar to the original NES controller. The controller is able to connect to a Wii Remote for use with Wii and Wii U Virtual Console games. The NES Classic Edition came with 30 games pre-installed, including Final Fantasy, Kid Icarus, The Legend of Zelda, Zelda II: The Adventure of Link, and Dr. Mario, among others. It was released in November 2016. Additional controllers were also available.[68]

The July 2016 release of the Pokémon Go mobile app by Niantic caused shares in Nintendo to double, due to investor misunderstanding that the software was the property of Nintendo. Later that month, Nintendo released a statement clarifying its relation with Niantic, Nintendo stated it owned 32% of Pokémon intellectual property owner The Pokémon Company, and though it would receive some licensing and other revenues from the game it expected the impact on Nintendo's total income to be limited. As a result of the statement Nintendo's share price fell substantially, losing 17% in one day of trading.[69][70] After a reduction in shareprice from the Pokémon Go peak, the company was still valued at over 100 times its net income, a price–earnings ratio greatly exceeding the average on the Nikkei 225.[71] Analysts speaking to Bloomberg L.P. and the Financial Times both commented on the potential future value of Nintendo's IP if transferred to the mobile phone game business.[71][72]

In August 2016, Nintendo of America sold 90% of its controlling stake (55%) in the Seattle Mariners to a group of investors led by mobile phone businessman John Stanton for $640 million.[73][74]

After the announcement of the mobile game Super Mario Run in September 2016, Nintendo's stock soared to just under its recent high point after the release and success of Pokémon Go earlier in the year, something noted by journalists as even more significant than Pokémon Go, as Super Mario Run was developed in-house by Nintendo, which was not the case with Pokémon Go.[75] In a December 2016 interview prior to the release of Super Mario Run, Miyamoto explained that the company believed that with some of their game franchises, "the longer you continue to make a series, the more complex the gameplay becomes, and the harder it becomes for new players to be able to get into the series", and that the company sees mobile games with simplified controls, such as Super Mario Run, not only allows them to "make a game that the broadest audience of people could play", but to also reintroduce these properties to newer audiences and draw them to their consoles.[76]

On 20 October 2016, Nintendo released a preview trailer about the NX, revealing the official name to be the Nintendo Switch.[77] According to Fils-Aimé, the console gave game developers new abilities to bring their creative concepts to life by opening up the concept of gaming without limits.[78] In December 2016, Nintendo released Super Mario Run for iOS devices, with the game surpassing over 50 million downloads within a week of its release. Kimishima stated that Nintendo would release a couple of mobile games each year from then on.[79]

On 31 January 2017, Nintendo stopped producing new Wii U consoles.[80][81]

In September 2017, Nintendo announced a partnership with the Chinese gaming company Tencent to publish a global version of their commercially successful mobile game, Honor of Kings, for the Nintendo Switch. The announcement lead some to believe that Nintendo could soon have a bigger footprint in China, a region where the Switch is not sold and is largely dominated by Tencent.[82] In November 2017, it was reported that Nintendo would be teaming up with Illumination, an animation division of Universal Pictures, to make an animated Mario film.[83][84][85] In April 2018, Nintendo announced that Kimishima would be stepping down as company president that June, with Shuntaro Furukawa, former managing executive officer and outside director of The Pokémon Company, succeeding him.[86]

In January 2019, Nintendo announced it had made $958 million in profit and $5.59 billion in revenue during 2018.[87] In February 2019, Nintendo of America president Reggie Fils-Aimé announced that he would be retiring, with Doug Bowser succeeding him on 15 April 2019.[88] In June 2019, Nintendo opened a second official retail store in Israel.[89]

In April 2020, it was announced that ValueAct Capital Partners had obtained $1.1 billion in Nintendo stock purchases, giving them an overall stake of 2% in Nintendo.[90]

Products

Home consoles

Color TV-Game

Released in 1977, Nintendo's Color TV-Game was Japan's best-selling first-generation console, with more than three million units sold.[91]:27

Nintendo Entertainment System

The Nintendo Entertainment System (NES) is an 8-bit video game console, which released in North America in 1985, and in Europe throughout 1986 and 1987. The console was initially released in Japan as the Family Computer (abbreviated as Famicom) in 1983. The best-selling gaming console of its time,[91]:349 the NES helped revitalize the US video game industry following the video game crash of 1983.[92] With the NES, Nintendo introduced a now-standard business model of licensing third-party developers, authorizing them to produce and distribute games for Nintendo's platform.[93] The NES was bundled with Super Mario Bros., one of the best-selling video games of all time, and received ports of Nintendo's most popular arcade games.[21]

Nintendo produced a limited run of the NES Classic Edition in 2016. The NES Classic System was a dedicated console modeled after an NES with 30 built-in classic first- and third-party games from the NES library. By the end of its production in April 2017, Nintendo shipped over two million units.[94]

Super Nintendo Entertainment System

The Super Nintendo Entertainment System (Super NES or SNES) is a 16-bit video game console, which was released in North America in 1991, and in Europe in 1992. The console was initially released in Japan in 1990 as the Super Famicom, officially adopting the colloquially abbreviated name of its predecessor. The console introduced advanced graphics and sound capabilities compared with other consoles at the time. Soon, the development of a variety of enhancement chips which were integrated onto each new game cartridge's circuit boards, progressed the SNES's competitive edge. While even crude three-dimensional graphics had previously rarely been seen on home consoles,[95] the Super NES's enhancement chips suddenly enabled a new caliber of games containing increasingly sophisticated faux 3D effects as seen in 1991's Pilotwings and 1992's Super Mario Kart. Argonaut Games developed the Super FX chip in order to replicate 3D graphics from their earlier Atari ST and Amiga Starglider series on the Super NES (more specifically, Starglider 2),[96] starting with Star Fox in 1993. The SNES is the bestselling console of the 16-bit era although having experienced a relatively late start and fierce competition from Sega's Mega Drive/Genesis console.

Nintendo also released a limited run of the Super NES Classic Edition in September 2017 through the end of the year. Like the NES Classic Edition, the Super NES Classic Edition is a dedicated console with 21 built-in games from its library, including the never-before-released Star Fox 2.

Nintendo 64

The Nintendo 64 was released in 1996, featuring 3D polygon model rendering capabilities and built-in multiplayer for up to four players. The system's controller introduced the analog stick and later introduced the Rumble Pak, an accessory for the controller that produces force feedback with compatible games. Both are the first such features to have come to market for home console gaming and eventually became the de facto industry standard.[97] Announced in 1995, prior to the console's 1996 launch, the 64DD ("DD" standing for "Disk Drive") was designed to enable the development of new genre of video games[98] by way of 64 MB writable magnetic disks, video editing, and Internet connectivity. Eventually released in Japan in 1999, the 64DD peripheral's commercial failure there resulted in only nine games being released and precluded release outside Japan.

GameCube

The GameCube (officially called Nintendo GameCube, abbreviated NGC in Japan and GCN in North America) was released in 2001, in Japan and North America, and in 2002 worldwide. The sixth-generation console is the successor to the Nintendo 64 and competed with Sony's PlayStation 2, Microsoft's Xbox, and Sega's Dreamcast. The GameCube is the first Nintendo console to use optical discs as its primary storage medium.[99] The discs are similar to the miniDVD format, but the system was not designed to play standard DVDs or audio CDs. Nintendo introduced a variety of connectivity options for the GameCube. The GameCube's game library has sparse support for Internet gaming, a feature that requires the use of the aftermarket GameCube Broadband Adapter and Modem Adapter. The GameCube supports connectivity to the Game Boy Advance, allowing players to access exclusive in-game features using the handheld as a second screen and controller.

Wii

The Wii was released during the holiday season of 2006 worldwide. The system features the Wii Remote controller, which can be used as a handheld pointing device and which detects movement in three dimensions. Another notable feature of the console is WiiConnect24, which enables it to receive messages and updates over the Internet while in standby mode.[100] It also features a game download service, called "Virtual Console", which features emulated games from past systems. Since its release, the Wii has spawned many peripheral devices, including the Wii Balance Board and Motion Plus, and has had several hardware revisions. The Wii Family Edition variant is identical to the original model, but is designed to sit horizontally and removes the GameCube compatibility. The Wii Mini is a smaller, redesigned Wii which lacks GameCube compatibility, online connectivity, the SD card slot and Wi-Fi support, and has only one USB port unlike the previous models' two.[101][102]

Wii U

The Wii U, the successor to the Wii, was released during the holiday season of 2012 worldwide.[103][104] The Wii U is the first Nintendo console to support high-definition graphics. The Wii U's primary controller is the Wii U GamePad, which features an embedded touchscreen. Each game may be designed to use this touchscreen as supplemental to the main TV, or as the only screen for Off-TV Play. The system supports most Wii controllers and accessories, and the more classically shaped Wii U Pro Controller.[105] The system is backward compatible with Wii software and accessories; this mode also utilizes Wii-based controllers, and it optionally offers the GamePad as its primary Wii display and motion sensor bar. The console has various online services powered by Nintendo Network, including the Nintendo eShop for online distribution of software and content, and Miiverse, a social network which can be variously integrated with games and applications. As of 31 March 2018, worldwide Wii U sales had totaled over 13 million units, with over 100 million games and other software for it sold.[106] It was discontinued on January 31, 2017.[80][81]

Nintendo Switch

On 17 March 2015, Nintendo announced a new "dedicated games platform with a brand new concept" with the codename "NX" that would be further revealed in 2016.[54][56] Reggie Fils-Aimé, president of Nintendo of America at the time, referred to NX as "our next home console" in a June 2015 interview with The Wall Street Journal.[57] In a later article on 16 October 2015, The Wall Street Journal relayed speculation from unnamed inside sources that, although the NX hardware specifications were unknown, it may be intended to feature "industry leading" hardware specifications and include both a console and a mobile unit that could either be used with the console or taken on the road for separate use. It was also reported that Nintendo had begun distributing software development kits (SDKs) for NX to third-party developers, with the unnamed source further speculating that these moves "[suggest that] the company is on track to introduce [NX] as early as [2016]."[58] At an investor's meeting on 27 April 2016, Nintendo announced that the NX would be released worldwide in March 2017.[59] In an interview with Asahi Shimbun in May 2016, Kimishima referred to the NX as "neither the successor to the Wii U nor to the 3DS", as well as it being a "new way of playing games," but it would "slow Wii U sales" upon reveal and dissemination.[60] In June 2016, Miyamoto stated that the reason Nintendo had not released any information on the "NX" up until that point was because they were afraid of imitators, saying he and Nintendo thought other companies could copy "an idea that [they're] working on."[107][108] The same day, Kimishima revealed during a Q&A session with investors that they were also researching virtual reality.[62] On 19 October 2016, Nintendo announced they would release a trailer for the console the following day.[109] The next day, Nintendo unveiled the trailer that revealed the final name of the platform called Nintendo Switch.[110] By March 2018, over 17 million Switch units had been sold worldwide.[111] As of 31 December 2019, there are over 52 milion copies sold.[112]

Handheld consoles

Game & Watch

Game & Watch is a line of handheld electronic games produced by Nintendo from 1980 to 1991. Created by game designer Gunpei Yokoi, they were originally conceived after Yokoi noticed a bored business man on the train playing around with his calculator,[18] and each Game & Watch features a single game to be played on an LCD screen in addition to a clock, an alarm, or both.[113] It was the earliest Nintendo product to garner major success.[114]

Game Boy

After the success of the Game & Watch series, Yokoi developed the Game Boy handheld console, which was released in 1989. Eventually becoming the bestselling handheld of all time, the Game Boy remained dominant for more than a decade, seeing critically and commercially popular games such as Pokémon Yellow released as late as 1998 in Japan, 1999 in North America, and 2000 in Europe. Incremental updates of the Game Boy, including Game Boy Pocket, Game Boy Light and Game Boy Color, did little to change the original formula, though the latter introduced color graphics to the Game Boy line.

Game Boy Advance

The first major update to its handheld line since 1989, the Game Boy Advance features improved technical specifications similar to those of the SNES. The Game Boy Advance SP was the first revision to the GBA line and introduced screen lighting and a clam shell design, while later iteration, the Game Boy Micro, brought a smaller form factor.

Nintendo DS

Although originally advertised as an alternative to the Game Boy Advance, the Nintendo DS replaced the Game Boy line after its initial release in 2004.[115] It was distinctive for its dual screens and a microphone, as well as a touch-sensitive lower screen. The Nintendo DS Lite brought a smaller form factor[116] while the Nintendo DSi features larger screens and two cameras,[117] and was followed by an even larger model, the Nintendo DSi XL, with a 90% bigger screen.[118]

Nintendo 3DS

Further expanding the Nintendo DS line, the Nintendo 3DS uses the process of autostereoscopy to produce a stereoscopic three-dimensional effect without glasses.[119] Released to major markets during 2011, the 3DS got off to a slow start, initially missing many key features that were promised before the system launched.[120] Partially as a result of slow sales, Nintendo stock declined in value. Subsequent price cuts and game releases helped to boost 3DS and 3DS software sales and to renew investor confidence in the company.[121] As of August 2013, the 3DS was the best selling console in the United States for four consecutive months.[122] The Nintendo 3DS XL was introduced in August 2012 and includes a 90% larger screen, a 4 GB SD card and extended battery life. In August 2013, Nintendo announced the cost-reduced Nintendo 2DS, a version of the 3DS without the 3D display. It has a slate-like design as opposed to the hinged, clamshell design of its predecessors.

A hardware revision, New Nintendo 3DS, was unveiled in August 2014. It is produced in a standard-sized model and a larger XL model; both models feature upgraded processors and additional RAM, an eye-tracking sensor to improve the stability of the autostereoscopic 3D image, colored face buttons, and near-field communication support for native use of Amiibo products. The standard-sized model also features slightly larger screens, and support for faceplate accessories.[123]

Nintendo Switch Lite

The Nintendo Switch Lite[b] is a handheld game console by Nintendo. It was released on September 20, 2019 as a handheld-only version of the Switch console, and is considered the successor to the New Nintendo 3DS.

Marketing

Nintendo of America has engaged in several high-profile marketing campaigns to define and position its brand. One of its earliest and most enduring slogans was "Now you're playing with power!", used first to promote its Nintendo Entertainment System.[citation needed] It modified the slogan to include "SUPER power" for the Super Nintendo Entertainment System, and "PORTABLE power" for the Game Boy.[citation needed] Its 1994 "Play It Loud!" campaign played upon teenage rebellion and fostered an edgy reputation.[citation needed] During the Nintendo 64 era, the slogan was "Get N or get out."[citation needed] During the GameCube era, the "Who Are You?" suggested a link between the games and the players' identities.[citation needed] The company promoted its Nintendo DS handheld with the tagline "Touching is Good."[citation needed] For the Wii, they used the "Wii would like to play" slogan to promote the console with the people who tried the games including Super Mario Galaxy and Super Paper Mario. The Nintendo 3DS used the slogan "Take a look inside".[citation needed] The Wii U used the slogan "How U will play next."[citation needed] The Nintendo Switch uses the slogan "Switch and Play" in North America, and "Play anywhere, anytime, with anyone" in Europe.[citation needed]

Logos

Used since the 1960s, Nintendo's most recognizable logo is the racetrack shape, especially the red-colored wordmark on a white background, primarily used in the Western markets from 1985 to 2006. In Japan, a monochromatic version that lacks a colored background is on Nintendo's own Famicom, Super Famicom, Nintendo 64, GameCube, and handheld console packaging and marketing. Since 2006, in conjunction with the launch of the Wii, Nintendo changed its logo to a gray variant that lacks a colored background inside the wordmark, making it transparent. Nintendo's official, corporate logo remains this variation.[124] For consumer products and marketing, a white variant on a red background has been used since 2015, and has been in full effect since the launch of the Nintendo Switch in 2017.

Company structure

Board of directors

Representative directors

Directors

- Shinya Takahashi, senior managing executive officer, general manager of Entertainment Planning & Development and supervisor of Business Development Division and Development Administration & Support Division.

- Ko Shiota, senior executive officer, general manager of Platform Technology Development

- Satoru Shibata, senior executive officer, general manager of marketing and licensing

Executive officers

- Satoshi Yamato, senior executive officer, president of Nintendo Sales Co., Ltd

- Hirokazu Shinshi, senior executive officer, chief director of manufacturing

- Yoshiaki Koizumi, senior executive officer, executive officer and deputy general manager of Entertainment Planning & Development

- Takashi Tezuka, executive officer, senior officer of Entertainment Planning & Development

- Hajime Murakami, executive officer, general Manager of Finance Administration Division

- Yusuke Beppu, executive officer, deputy general manager of Business Development Division

- Kentaro Yamagishi, executive officer, chief director of General Affairs

- Doug Bowser, executive officer, president and COO of Nintendo of America

- Stephan Bole, executive officer, president and COO of Nintendo of Europe

Divisions

Nintendo's internal research and development operations are divided into three main divisions: Nintendo Entertainment Planning & Development (or EPD), the main software development division of Nintendo, which focuses on video game and software development; Nintendo Platform Technology Development (or PTD), which focuses on home and handheld video game console hardware development; and Nintendo Business Development (or NBD), which focuses on refining business strategy and is responsible for overseeing the smart device arm of the business.

Entertainment Planning & Development (EPD)

The Nintendo Entertainment Planning & Development division is the primary software development division at Nintendo, formed as a merger between their former Entertainment Analysis & Development and Software Planning & Development divisions in 2015. Led by Shinya Takahashi, the division holds the largest concentration of staff at the company, housing more than 800 engineers and designers.

Platform Technology Development (PTD)

The Nintendo Platform Technology Development division is a combination of Nintendo's former Integrated Research & Development (or IRD) and System Development (or SDD) divisions. Led by Ko Shiota, the division is responsible for designing hardware and developing Nintendo's operating systems, developer environment and internal network as well as maintenance of the Nintendo Network.

Business Development (NBD)

The Nintendo Business Development division was formed following Nintendo's foray into software development for smart devices such as mobile phones and tablets. They are responsible for refining Nintendo's business model for the dedicated video game system business, and for furthering Nintendo's venture into development for smart devices.

International divisions

The exterior of Nintendo's main headquarters in Kyoto, Japan.

Nintendo of America headquarters in Redmond, Washington.

Nintendo of Europe headquarters in Frankfurt, Germany.

Nintendo Co., Ltd.

Headquartered in Kyoto, Japan since the beginning, Nintendo Co., Ltd. oversees the organization's global operations and manages Japanese operations specifically. The company's two major subsidiaries, Nintendo of America and Nintendo of Europe, manage operations in North America and Europe respectively. Nintendo Co., Ltd.[127] moved from its original Kyoto location to a new office in Higashiyama-ku, Kyoto, in 2000, this became the research and development building when the head office relocated to its present[update] location in Minami-ku, Kyoto.[128]

Nintendo of America

Nintendo founded its North American subsidiary in 1980 as Nintendo of America (NoA). Hiroshi Yamauchi appointed his son-in-law Minoru Arakawa as president, who in turn hired his own wife and Yamauchi's daughter Yoko Yamauchi as the first employee. The Arakawa family moved from Vancouver to select an office in Manhattan, New York, due to its central status in American commerce. Both from extremely affluent families, their goals were set more by achievement than money—and all their seed capital and products would now also be automatically inherited from Nintendo in Japan, and their inaugural target is the existing $8 billion-per-year coin-op arcade video game market and largest entertainment industry in the US, which already outclassed movies and television combined. During the couple's arcade research excursions, NoA hired gamer youths to work in the filthy, hot, ratty warehouse in New Jersey for the receiving and service of game hardware from Japan.[91]:94–103

In late 1980 NoA contracted the Seattle-based arcade sales and distribution company Far East Video, consisting solely of experienced arcade salespeople Ron Judy and Al Stone. The two had already built a decent reputation and a distribution network, founded specifically for the independent import and sales of games from Nintendo because the Japanese company had for years been the under-represented maverick in America. Now as direct associates to the new NoA, they told Arakawa they could always clear all Nintendo inventory if Nintendo produced better games. Far East Video took NoA's contract for a fixed per-unit commission on the exclusive American distributorship of Nintendo games, to be settled by their Seattle-based lawyer, Howard Lincoln.[91]:94–103

Based on favorable test arcade sites in Seattle, Arakawa wagered most of NoA's modest finances on a huge order of 3,000 Radar Scope cabinets. He panicked when the game failed in the fickle market upon its arrival from its four-month boat ride from Japan. Far East Video was already in financial trouble due to declining sales and Ron Judy borrowed his aunt's life savings of $50,000, while still hoping Nintendo would develop its first Pac-Man-sized hit. Arakawa regretted founding the Nintendo subsidiary, with the distressed Yoko trapped between her arguing husband and father.[91]:103–105

Amid financial threat, Nintendo of America relocated from Manhattan to the Seattle metro to remove major stressors: the frenetic New York and New Jersey lifestyle and commute, and the extra weeks or months on the shipping route from Japan as was suffered by the Radar Scope disaster. With the Seattle harbor being the US's closest to Japan at only nine days by boat, and having a lumber production market for arcade cabinets, Arakawa's real estate scouts found a 60,000-square-foot (5,600 m2) warehouse for rent containing three offices—one for Arakawa and one for Judy and Stone.[91]:105–106 This warehouse in the Tukwila suburb was owned by Mario Segale after whom the Mario character would be named, and was initially managed by former Far East Video employee Don James.[91]:109 After one month, James recruited his college friend Howard Phillips as assistant, who soon took over as warehouse manager.[129]:10:00, 17:25[130][131][132][133][134][129]:11:50 The company remained at fewer than 10 employees for some time, handling sales, marketing, advertising, distribution, and limited manufacturing[135]:160 of arcade cabinets and Game & Watch handheld units, all sourced and shipped from Nintendo.

Arakawa was still panicked over NoA's ongoing financial crisis. With the parent company having no new game ideas, he had been repeatedly pleading for Yamauchi to reassign some top talent away from existing Japanese products to develop something for America—especially to redeem the massive dead stock of Radar Scope cabinets. Since all of Nintendo's key engineers and programmers were busy, and with NoA representing only a tiny fraction of the parent's overall business, Yamauchi allowed only the assignment of Gunpei Yokoi's young assistant who had no background in engineering, Shigeru Miyamoto.[91]:106

NoA's staff—except the sole young gamer Howard Phillips—were uniformly revolted at the sight of the freshman developer Miyamoto's debut game, which they had imported in the form of emergency conversion kits for the overstock of Radar Scope cabinets.[91]:109 The kits transformed the cabinets into NoA's massive windfall gain of $280 million from Miyamoto's smash hit Donkey Kong in 1981–1983 alone.[91]:111[136] They sold 4,000 new arcade units each month in America, making the 24-year-old Phillips "the largest volume shipping manager for the entire Port of Seattle".[133] Arakawa used these profits to buy 27 acres (11 ha) of land in Redmond in July 1982[91]:113 and to perform the $50 million launch of the Nintendo Entertainment System in 1985 which revitalized the entire video game industry from its devastating 1983 crash.[137][138] A second warehouse in Redmond was soon secured, and managed by Don James. The company stayed at around 20 employees for some years.

The organization was reshaped nationwide in the following decades, and those core sales and marketing business functions are now directed by the office in Redwood City, California. The company's distribution centers are Nintendo Atlanta in Atlanta, Georgia, and Nintendo North Bend in North Bend, Washington. As of 2007[update], the 380,000-square-foot (35,000 m2) Nintendo North Bend facility processes more than 20,000 orders a day to Nintendo customers, which include retail stores that sell Nintendo products in addition to consumers who shop Nintendo's website.[139] Nintendo of America operates two retail stores in the United States: Nintendo New York on Rockefeller Plaza in New York City, which is open to the public; and Nintendo Redmond, co-located at NoA headquarters in Redmond, Washington, which is open only to Nintendo employees and invited guests. Nintendo of America's Canadian branch, Nintendo of Canada, is based in Vancouver, British Columbia with a distribution center in Toronto, Ontario.[citation needed] Nintendo Treehouse is NoA's localization team, composed of around 80 staff who are responsible for translating text from Japanese to English, creating videos and marketing plans, and quality assurance.[140]

Nintendo of Europe

Nintendo's European subsidiary was established in June 1990,[141] based in Großostheim, Germany.[142] The company handles operations across Europe excluding Scandinavia, as well as South Africa.[141] Nintendo of Europe's United Kingdom branch (Nintendo UK)[143] handles operations in that country and in Ireland from its headquarters in Windsor, Berkshire. In June 2014, NOE initiated a reduction and consolidation process, yielding a combined 130 layoffs: the closing of its office and warehouse, and termination of all employment, in Großostheim; and the consolidation of all of those operations into, and terminating some employment at, its Frankfurt location.[144][145] As of July 2018, the company employs 850 people.[146] In 2019, NoE signed with Tor Gaming Ltd. for official distribution in Israel.[147]

Nintendo Australia

Nintendo's Australian subsidiary is based in Melbourne, Victoria. It handles the publishing, distribution, sales, and marketing of Nintendo products in Australia, New Zealand, and Oceania (Cook Islands, Fiji, New Caledonia, Papua New Guinea, Samoa, and Vanuatu). It also manufactures some Wii games locally. Nintendo Australia is also a third-party distributor of some games from Rising Star Games, Bandai Namco Entertainment, Atlus, The Tetris Company, Sega, Koei Tecmo, and Capcom.

iQue

Originally a Chinese joint venture between its founder, Wei Yen, and Nintendo, manufactures and distributes official Nintendo consoles and games for the mainland Chinese market, under the iQue brand. The product lineup for the Chinese market is considerably different from that for other markets. For example, Nintendo's only console in China is the iQue Player, a modified version of the Nintendo 64. In 2013, the company became a fully owned subsidiary of Nintendo.[148][149]

Nintendo of Korea

Nintendo's South Korean subsidiary was established on 7 July 2006, and is based in Seoul.[150] In March 2016, the subsidiary was heavily downsized due to a corporate restructuring after analyzing shifts in the current market, laying off 80% of its employees, leaving only ten people, including CEO Hiroyuki Fukuda. This did not affect any games scheduled for release in South Korea, and Nintendo continued operations there as usual.[151][152]

Subsidiaries

Although most of the research and development is being done in Japan, there are some R&D facilities in the United States, Europe and China that are focused on developing software and hardware technologies used in Nintendo products. Although they all are subsidiaries of Nintendo (and therefore first party), they are often referred to as external resources when being involved in joint development processes with Nintendo's internal developers by the Japanese personal involved. This can be seen in the Iwata asks... interview series.[153] Nintendo Software Technology (NST) and Nintendo Technology Development (NTD) are located in Redmond, Washington, United States, while Nintendo European Research & Development (NERD) is located in Paris, France, and Nintendo Network Service Database (NSD) is located in Kyoto, Japan.

Most external first-party software development is done in Japan, since the only overseas subsidiary is Retro Studios in the United States. Although these studios are all subsidiaries of Nintendo, they are often referred to as external resources when being involved in joint development processes with Nintendo's internal developers by the Nintendo Entertainment Planning & Development (EPD) division. 1-Up Studio and Nd Cube are located in Tokyo, Japan, while Monolith Soft has one studio located in Tokyo and another in Kyoto. Retro Studios is located in Austin, Texas.

Nintendo also established The Pokémon Company alongside Creatures and Game Freak in order to effectively manage the Pokémon brand. Similarly, Warpstar Inc. was formed through a joint investment with HAL Laboratory, which was in charge of the Kirby: Right Back at Ya! animated series.

Additional distributors

Bergsala

Bergsala, a third-party company based in Sweden, exclusively handles Nintendo operations in the Scandinavian region. Bergsala's relationship with Nintendo was established in 1981 when the company sought to distribute Game & Watch units to Sweden, which later expanded to the NES console by 1986. Bergsala were the only non-Nintendo owned distributor of Nintendo's products,[154] up until 2019 when Tor Gaming gained distribution rights in Israel.

Tencent

Nintendo has partnered with Tencent to release Nintendo products in China, following the lifting of the country's console ban in 2015. In addition to distributing hardware, Tencent will help bring Nintendo's games through the governmental approval process for video game software.[155]

Tor Gaming

In January 2019, it was reported by ynet and IGN Israel that negotiations about official distribution of Nintendo products in the country were ongoing[147]. After two months, IGN Israel announced that Tor Gaming Ltd., a company that established in earlier 2019, gained a distribution agreement with Nintendo of Europe, handling official retailing beginning at the start of March[156], followed by opening an official online store the next month[157][158]. In June 2019, Tor Gaming launched an official Nintendo Store at Dizengoff Center in Tel Aviv, making it the second official Nintendo Store worldwide, 13 years after NYC[89].

Policy

Content guidelines

For many years, Nintendo had a policy of strict content guidelines for video games published on its consoles. Although Nintendo allowed graphic violence in its video games released in Japan, nudity and sexuality were strictly prohibited. Former Nintendo president Hiroshi Yamauchi believed that if the company allowed the licensing of pornographic games, the company's image would be forever tarnished.[91] Nintendo of America went further in that games released for Nintendo consoles could not feature nudity, sexuality, profanity (including racism, sexism or slurs), blood, graphic or domestic violence, drugs, political messages or religious symbols (with the exception of widely unpracticed religions, such as the Greek Pantheon).[159] The Japanese parent company was concerned that it may be viewed as a "Japanese Invasion" by forcing Japanese community standards on North American and European children. Past the strict guidelines, some exceptions have occurred: Bionic Commando (though swastikas were eliminated in the US version), Smash TV and Golgo 13: Top Secret Episode contain human violence, the latter also containing implied sexuality and tobacco use; River City Ransom and Taboo: The Sixth Sense contain nudity, and the latter also contains religious images, as do Castlevania II and III.

A known side effect of this policy is the Genesis version of Mortal Kombat having more than double the unit sales of the Super NES version, mainly because Nintendo had forced publisher Acclaim to recolor the red blood to look like white sweat and replace some of the more gory graphics in its release of the game, making it less violent.[160] By contrast, Sega allowed blood and gore to remain in the Genesis version (though a code is required to unlock the gore). Nintendo allowed the Super NES version of Mortal Kombat II to ship uncensored the following year with a content warning on the packaging.[161]

Video game ratings systems were introduced with the Entertainment Software Rating Board of 1994 and the Pan European Game Information of 2003, and Nintendo discontinued most of its censorship policies in favor of consumers making their own choices. Today, changes to the content of games are done primarily by the game's developer or, occasionally, at the request of Nintendo. The only clear-set rule is that ESRB AO-rated games will not be licensed on Nintendo consoles in North America,[162] a practice which is also enforced by Sony and Microsoft, its two greatest competitors in the present market. Nintendo has since allowed several mature-content games to be published on its consoles, including these: Perfect Dark, Conker's Bad Fur Day, Doom, Doom 64, BMX XXX, the Resident Evil series, Killer7, the Mortal Kombat series, Eternal Darkness: Sanity's Requiem, BloodRayne, Geist, Dementium: The Ward, Bayonetta 2, Devil's Third, and Fatal Frame: Maiden of Black Water. Certain games have continued to be modified, however. For example, Konami was forced to remove all references to cigarettes in the 2000 Game Boy Color game Metal Gear Solid (although the previous NES version of Metal Gear and the subsequent GameCube game Metal Gear Solid: The Twin Snakes both included such references, as did Wii game MadWorld), and maiming and blood were removed from the Nintendo 64 port of Cruis'n USA.[163] Another example is in the Game Boy Advance game Mega Man Zero 3, in which one of the bosses, called Hellbat Schilt in the Japanese and European releases, was renamed Devilbat Schilt in the North American localization. In North America releases of the Mega Man Zero games, enemies and bosses killed with a saber attack do not gush blood as they do in the Japanese versions. However, the release of the Wii was accompanied by a number of even more controversial games, such as Manhunt 2, No More Heroes, The House of the Dead: Overkill, and MadWorld, the latter three of which were published exclusively for the console.

License guidelines

Nintendo of America also had guidelines before 1993 that had to be followed by its licensees to make games for the Nintendo Entertainment System, in addition to the above content guidelines.[91] Guidelines were enforced through the 10NES lockout chip.

- Licensees were not permitted to release the same game for a competing console until two years had passed.

- Nintendo would decide how many cartridges would be supplied to the licensee.

- Nintendo would decide how much space would be dedicated such as for articles and advertising in the Nintendo Power magazine.

- There was a minimum number of cartridges that had to be ordered by the licensee from Nintendo.

- There was a yearly limit of five games that a licensee may produce for a Nintendo console.[91]:215 This rule was created to prevent market over-saturation, which had contributed to the North American video game crash of 1983.

The last rule was circumvented in a number of ways; for example, Konami, wanting to produce more games for Nintendo's consoles, formed Ultra Games and later Palcom to produce more games as a technically different publisher.[91] This disadvantaged smaller or emerging companies, as they could not afford to start additional companies. In another side effect, Square Co (now Square Enix) executives have suggested that the price of publishing games on the Nintendo 64 along with the degree of censorship and control that Nintendo enforced over its games, most notably Final Fantasy VI, were factors in switching its focus towards Sony's PlayStation console.[citation needed]

In 1993, a class action suit was taken against Nintendo under allegations that their lockout chip enabled unfair business practices. The case was settled, with the condition that California consumers were entitled to a $3 discount coupon for a game of Nintendo's choice.[164]

Intellectual property protection

Nintendo has generally been proactive to assure its intellectual property in both hardware and software is protected. With the NES system, Nintendo employed a lock-out system that only allowed authorizes game cartridges they manufactured to be playable on the system.

Nintendo has used emulation by itself or licensed from third parties to provide means to re-release games from their older platforms on newer systems, with Virtual Console, which re-released classic games as downloadable titles, the NES and SNES library for Nintendo Switch Online subscribers, and with dedicated consoles like the NES Mini and SNES Mini.[citation needed] However, Nintendo has taken a hard stance against unlicensed emulation of its video games and consoles, stating that it is the single largest threat to the intellectual property rights of video game developers.[165] Further, Nintendo has taken action against fan-made games which have used significant facets of their IP, issuing cease & desist letters to these projects or Digital Millennium Copyright Act-related complaints to services that host these projects.[166]

In recent years, Nintendo has taken legal action against sites that knowingly distribute ROM images of their games. On 19 July 2018, Nintendo sued Jacob Mathias, the owner of ROM image distribution websites LoveROMs and LoveRetro, for "brazen and mass-scale infringement of Nintendo's intellectual property rights."[167] Nintendo settled with Mathias in November 2018 for more than US$12 million along with relinquishing all ROM images in their ownership. While Nintendo is likely to have agreed to a smaller fine in private, the large amount was seen as a deterrent to prevent similar sites from sharing ROM images.[168] Nintendo filed a separate suit against RomUniverse in September 2019 which also offered infringing copies of Nintendo DS and Switch games in addition to ROM images.[169] Nintendo also successfully won a suit in the United Kingdom that same month to force the major Internet service providers in the country to block access to sites that offered copyright-infringing copies of Switch software or hacks for the Nintendo Switch to run unauthorized software.[170] Ironically, individuals who hacked the Wii Virtual Console version of Super Mario Bros. discovered that the ROM image Nintendo used had likely been downloaded from a ROM distribution site.[171]

In a notable case, Nintendo sought enforcement action against a hacker that for several years had gotten into Nintendo's internal database by various means including phishing to obtain plans of what games and hardware they had planned to announce for upcoming shows like E3, leaking this information to the Internet, impacting how Nintendo's own announcements were received. Though the person was a minor when Nintendo brought the United States Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) to investigate, and had been warned by the FBI to desist, the person continued over 2018 and 2019 as an adult, taunting their actions over social media. They were arrested in July 2019, and in addition to documents confirming the hacks, the FBI found a number of unauthorized game files as well as child pornography on their computers, leading to their admission of guilt for all crimes in January 2020.[172] Similarly, Nintendo spent significant time to identify who had leaked information about Pokémon Sword and Shield several weeks before its planned Nintendo Directs, ultimately tracing the leaks back to a Portugal game journalist who leaked the information from official review copies of the game and subsequently severed ties with the publication.[173]

Despite efforts to protects its IP, a major leak of documents, including source code, design documents, hardware drawings and documentation and other internal information primarily related to the Nintendo 64, GameCube, and Wii, appeared in May 2020. The leak may have been related to BroadOn, a company that Nintendo had contracted to help with the Wii's design,[174] but could also be the work of Zammis Clark, a Malwarebytes employee and hacker who infiltrated Nintendo's servers between March and May 2018.[175]

Seal of Quality

The gold sunburst seal was first used by Nintendo of America, and later Nintendo of Europe. It is displayed on any game, system, or accessory licensed for use on one of its video game consoles, denoting the game has been properly approved by Nintendo. The seal is also displayed on any Nintendo-licensed merchandise, such as trading cards, game guides, or apparel, albeit with the words "Official Nintendo Licensed Product".[176]

In 2008, game designer Sid Meier cited the Seal of Quality as one of the three most important innovations in video game history, as it helped set a standard for game quality that protected consumers from shovelware.[177]

NTSC regions

In NTSC regions, this seal is an elliptical starburst named the "Official Nintendo Seal". Originally, for NTSC countries, the seal was a large, black and gold circular starburst. The seal read as follows: "This seal is your assurance that NINTENDO has approved and guaranteed the quality of this product." This seal was later altered in 1988: "approved and guaranteed" was changed to "evaluated and approved." In 1989, the seal became gold and white, as it currently appears, with a shortened phrase, "Official Nintendo Seal of Quality." It was changed in 2003 to read "Official Nintendo Seal."[176]

The seal currently reads:[178]

The official seal is your assurance that this product is licensed or manufactured by Nintendo. Always look for this seal when buying video game systems, accessories, games and related products.

PAL regions

In PAL regions, the seal is a circular starburst named the "Original Nintendo Seal of Quality." Text near the seal in the Australian Wii manual states:

This seal is your assurance that Nintendo has reviewed this product and that it has met our standards for excellence in workmanship, reliability and entertainment value. Always look for this seal when buying games and accessories to ensure complete compatibility with your Nintendo product.[179]

Charitable projects

In 1992, Nintendo teamed with the Starlight Children's Foundation to build Starlight Fun Center mobile entertainment units and install them in hospitals.[180] 1,000 Starlight Nintendo Fun Center units were installed by the end of 1995.[180] These units combine several forms of multimedia entertainment, including gaming, and serve as a distraction to brighten moods and boost kids' morale during hospital stays.[181]

Environmental record

Nintendo has consistently been ranked last in Greenpeace's "Guide to Greener Electronics" due to Nintendo's failure to publish information.[182] Similarly, they are ranked last in the Enough Project's "Conflict Minerals Company Rankings" due to Nintendo's refusal to respond to multiple requests for information.[183]

Like many other electronics companies, Nintendo offers a take-back recycling program which allows customers to mail in old products they no longer use. Nintendo of America claimed that it took in 548 tons of returned products in 2011, 98% of which was either reused or recycled.[184]

Trademark

During the peak of Nintendo's success in the video game industry in the 1990s, their name was ubiquitously used to refer to any video game console, regardless of the manufacturer. To prevent their trademark from becoming generic, Nintendo pushed usage of the term "game console", and succeeded in preserving their trademark.[185][186]

See also

- List of Nintendo development teams

- Lists of Nintendo characters

- Lists of Nintendo games

- Lewis Galoob Toys, Inc. v. Nintendo of America, Inc.

- Universal City Studios, Inc. v. Nintendo Co., Ltd.

Notes

References

- ^ "Consolidated Financial Statements" (PDF). Retrieved 25 April 2019.

- ^ 会社概要 [Company Profile]. Nintendo Co., Ltd. Retrieved 5 May 2020.

- ^ David Cole (2 November 2018). Who is worth more? Sony and Nintendo market value (Report). DFC Intelligence. Retrieved 3 April 2019.

- ^ Kohler, Chris. "September 23, 1889: Success Is in the Cards for Nintendo". Wired. Retrieved 30 June 2017.

- ^ a b Modojo (11 August 2011). "Before Mario: Nintendo's Playing Cards, Toys, and Love Hotels". Business Insider. Retrieved 23 October 2015.

- ^ a b c "Nintendo History". Nintendo of Europe GmbH. Archived from the original on 4 September 2012. Retrieved 27 May 2014.

- ^ "Nintendo's card game product". nintendo. Retrieved 24 September 2016.

- ^ "List of Japan contract bridge league tournaments" (in Japanese). jcbl. Archived from the original on 24 June 2008. Retrieved 24 September 2016.

- ^ "Nintendo Corporation, Limited". Archived from the original (doc) on 22 July 2012. Retrieved 22 February 2011.

- ^ Ashcraft, Brian (3 August 2017). "'Nintendo' Probably Doesn't Mean What You Think It Does". Kotaku. Retrieved 4 August 2017.

- ^ "As Nintendo turns 125, 6 things you may not know about this gaming giant". NDTV Gadgets. NDTV. 23 September 2014. Retrieved 14 July 2015.

- ^ "Freelancers!: A Revolution in the Way We Work". Google Books.

- ^ "The Story of Nintendo". Google Books.

- ^ a b "Famous Names in Gaming". CBS. Archived from the original on 11 May 2013. Retrieved 13 June 2010.

- ^ "Iwata Asks-Punch-Out!!". Nintendo. Archived from the original on 10 August 2009. Retrieved 7 July 2009.

- ^ "Nintendo Will No Longer Produce Coin-Op Equipment". Cashbox. 5 September 1992. Retrieved 10 December 2019.

- ^ "Nintendo Stops Games Manufacturing; But Will Continue Supplying Software". Cashbox. 12 September 1992. Retrieved 10 December 2019.

- ^ a b Crigger, Lara (6 March 2007). "The Escapist: Searching for Gunpei Yokoi". The Escapist. Retrieved 27 May 2014.

- ^ "Nintendo Wins Emmy For DS And Wii Engineering". News.sky.com. 9 January 2008. Archived from the original on 11 October 2012. Retrieved 30 August 2010.

- ^ Magrino, Tom (8 January 2008). "CES '08: Nintendo wins second Emmy". Gamespot.com. Retrieved 30 August 2010.

- ^ a b Nagata, Kazuaki, "Nintendo secret: It's all in the game", The Japan Times, 10 March 2009, p. 3.

- ^ Kent 2001, p. 431Sonic was an immediate hit, and many consumers who had been loyally waiting for Super NES to arrive now decided to purchase Genesis. ... The fiercest competition in the history of video games was about to begin.

- ^ "Tidbits...". Electronic Gaming Monthly. No. 78. Ziff Davis. January 1996. p. 24.

- ^ "Quick Hits". GamePro. No. 89. IDG. February 1996. p. 17.

- ^ a b McLaughlin, Rus (29 July 2008). "IGN Presents the History of Rare". IGN. Archived from the original on 5 August 2008. Retrieved 17 May 2012.

- ^ Frischling, Bill. "Sideline Play." The Washington Post (1974–Current file): 11. ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Washington Post (1877–1995). 25 October 1995. Web. 24 May 2012.

- ^ Boyer, Steven. "A Virtual Failure: Evaluating the Success of Nintendos Virtual Boy." Velvet Light Trap.64 (2009): 23–33. ProQuest Research Library. Web. 24 May 2012.

- ^ Snow, Blake (4 May 2007). "The 10 Worst-Selling Consoles of All Time". GamePro. Archived from the original on 7 June 2011. Retrieved 12 June 2010.

- ^ "Ultra 64 Tech Specs". Next Generation. No. 14. Imagine Media. February 1996. p. 40.

Genyo Takeda: I think that the reason why we are not emphasizing benchmark performance figures is that Nintendo has a kind of history where the hardware design is just to give the creator and designer some inspiration to make the games. Evaluating hardware has to be done by playing games. That's Nintendo's philosophy.

- ^ Miller, Cyndee. "Sega Vs. Nintendo: This Fights almost as Rough as their Video Games." Marketing News 28.18 (1994): 1-. ABI/INFORM Global; ProQuest Research Library. Web. 24 May 2012.

- ^ Wade, Kenneth Kyle (17 December 2004). "History of Retro Studios". N-sider. Archived from the original on 7 August 2011. Retrieved 19 July 2007.

- ^ "Yamauchi Retires". IGN. 24 May 2002. Retrieved 19 July 2015.

- ^ Thomas, Lucas M. (24 May 2012). "Hiroshi Yamauchi: Nintendo's Legendary President". IGN. Retrieved 19 July 2015.

- ^ Kageyama, Yuri (12 July 2015). "Nintendo President Satoru Iwata Dies of Tumor". Associated Press. Tokyo, Japan. Archived from the original on 4 September 2015. Retrieved 12 July 2015.

- ^ Stack, Liam (13 July 2015). "Satoru Iwata, Nintendo Chief Executive, Dies at 55". The New York Times. Retrieved 13 July 2015.

- ^ "Nikkei talks with Nintendo's Yamauchi and Iwata". GameScience. Archived from the original on 27 January 2006. Retrieved 27 May 2014.

- ^ Metts, Jonathan (13 February 2004). "Iwata, Yamauchi Speak Out on Nintendo DS". Nintendo Worldwide Report. Retrieved 27 May 2014.

- ^ Constantine, John. "Rise to Heaven: Five Years of Nintendo DS". 1UP.com. Archived from the original on 12 June 2014. Retrieved 27 May 2014.

- ^ "The Zen of Wi-Fi". Famitsu (in Japanese). Translation. March 2006. Retrieved 13 November 2015.CS1 maint: others (link)

- ^ "Inside Nintendo's ES Open-Source Operating System". Gamasutra. 4 December 2007. Retrieved 28 December 2015.

- ^ "ES operating system". Nintendo. Retrieved 28 December 2015.

- ^ Gantayat, Anoop. "Xenosaga Developer Switches Sides". IGN. Retrieved 25 May 2014.

- ^ Fletcher. "Nintendo acquires video research/middleware company Mobiclip". Joystiq. Retrieved 25 May 2014.

- ^ "Slow Wii U sales send Nintendo shares into a downward spiral". 19 January 2014. Retrieved 7 April 2014.

- ^ "Nintendo Reports Weak Wii U Sales, Cuts Projections by 2/3rds". 18 January 2014. Retrieved 18 January 2020.

- ^ Leadbetter, Richard (12 December 2012). "Nintendo Wii Mini review". Eurogamer. Retrieved 25 February 2019.

- ^ パナソニック・任天堂、ゲーム機操作法を共同開発. Nikkei (in Japanese). Retrieved 25 May 2014.

- ^ "Nintendo Head Takes 50% Pay Cut, Outlines Smart Device Strategy". 30 January 2014. Retrieved 30 January 2020.

- ^ "Nintendo executives take pay cuts after profits tumble". 29 January 2014. Retrieved 31 May 2014.

- ^ Good, Owen S. (10 January 2015). "Nintendo ends console and game distribution in Brazil, citing high taxes". Polygon. Retrieved 5 February 2020.

- ^ Takashi Amano (12 July 2015). "Satoru Iwata, Nintendo President Who Introduced Wii, Dies". Bloomberg News. Bloomberg L.P. Retrieved 14 July 2015.

- ^ "Notice Regarding Personnel Change of a Representative Director and Role Changes of Directors" (PDF). Nintendo. 14 September 2015. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 September 2015. Retrieved 14 September 2015.

- ^ Russell, Jon. "Nintendo Partners With DeNA To Bring Its Games And IP To Smartphones". TechCrunch. Retrieved 17 March 2015.

- ^ a b c "March 17, Wed. 2015 Presentation Title". nintendo.co.jp. Retrieved 26 October 2015.

- ^ Kohler, Chris (28 October 2015). "Mii Avatars Star in Nintendo's First Mobile Game This March". Wired. Condé Nast. Retrieved 29 October 2015.

- ^ a b Westaway, Luke. "Nintendo will make games for phones, new 'NX' system". CNet. Retrieved 17 March 2015.

- ^ a b Needleman, Sarah E. "Nintendo's Reggie Fils-Aime Talks Amiibo and the 'Skylanders' Deal". WSJ. Retrieved 21 May 2016.

- ^ a b Mochizuki, Takashi (16 October 2015). "Nintendo Begins Distributing Software Kit for New NX Platform". The Wall Street Journal. Dow Jones & Company. Retrieved 26 October 2015.

- ^ a b Reilly, Luke (27 April 2016). "Nintendo NX Will Launch In March 2017". IGN. Ziff Davis. Retrieved 27 April 2016.

- ^ a b "Nintendo NX 'is neither the successor to the Wii U nor to the 3DS'". VG247.com. Retrieved 21 May 2016.