Opioid epidemic

An opioid epidemic is the overuse or misuse of addictive opioid drugs with significant medical, social and economic consequences, including overdose deaths.

Opioids are a diverse class of moderately strong painkillers, including oxycodone (commonly sold under the trade names OxyContin and Percocet), hydrocodone (Vicodin, Norco) and a very strong painkiller, fentanyl, which is synthesized to resemble other opiates such as opium-derived morphine and heroin.[1] The potency and availability of these substances, despite their high risk of addiction and overdose, have made them popular both as medical treatments and as recreational drugs. Due to their sedative effects on the part of the brain which regulates breathing, the respiratory center of the medulla oblongata, opioids in high doses present the potential for respiratory depression and may cause respiratory failure and death.[2]

Opioids are effective for treating acute pain,[3] but are less useful for treating chronic (long term) pain,[4] as the risks often outweigh the benefits.[4]

United States[edit]

What the U.S. Surgeon General dubbed "The Opioid Crisis" likely began with over-prescription of opioids in the 1990s, which led to them becoming the most prescribed class of medications in the United States. Opioids initiated for post surgery or pain management are one of the leading causes of opioid misuse, where approximately 6% of people continued opioid use after trauma or surgery.[5]

When people continue to use opioids beyond what a doctor prescribes, whether to minimize pain or induce euphoric feelings, it can mark the beginning stages of an opiate addiction, with a tolerance developing and eventually leading to dependence, when a person relies on the drug to prevent withdrawal symptoms.[6] Writers have pointed to a widespread desire among the public to find a pill for any problem, even if a better solution might be a lifestyle change, such as exercise, improved diet, and stress reduction.[7][8][9] Opioids are relatively inexpensive, and alternative interventions, such as physical therapy, may not be affordable.[10]

In the late 1990s, around 100 million people or a third of the U.S. population were estimated to be affected by chronic pain. This led to a push by drug companies and the federal government to expand the use of painkilling opioids.[11] In addition to this, organizations like the Joint Commission began to push for more attentive physician response to patient pain, referring to pain as the fifth vital sign. This exacerbated the already increasing number of opioids being prescribed by doctors to patients.[12] Between 1991 and 2011, painkiller prescriptions in the U.S. tripled from 76 million to 219 million per year, and as of 2016 more than 289 million prescriptions were written for opioid drugs per year.[13]:43

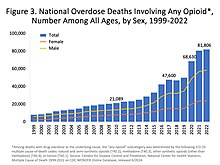

Mirroring the growth of opioid pain relievers prescribed is an increase in the admissions for substance abuse treatments and opioid-related deaths. This illustrates how legitimate clinical prescriptions of pain relievers are being diverted through an illegitimate market, leading to misuse, addiction, and death.[14] With the increase in volume, the potency of opioids also increased. By 2002, one in six drug users were being prescribed drugs more powerful than morphine; by 2012, the ratio had doubled to one-in-three.[11] The most commonly prescribed opioids have been oxycodone and hydrocodone.

The epidemic has been described as a "uniquely American problem".[15] The structure of the US healthcare system, in which people not qualifying for government programs are required to obtain private insurance, favors prescribing drugs over more expensive therapies. According to Professor Judith Feinberg, "Most insurance, especially for poor people, won't pay for anything but a pill."[16] Prescription rates for opioids in the US are 40 percent higher than the rate in other developed countries such as Germany or Canada.[17] While the rates of opioid prescriptions increased between 2001 and 2010, the prescription of non-opioid pain relievers (aspirin, ibuprofen, etc.) decreased from 38% to 29% of ambulatory visits in the same time period,[18] and there has been no change in the amount of pain reported in the U.S.[19] This has led to differing medical opinions, with some noting that there is little evidence that opioids are effective for chronic pain not caused by cancer.[20]

Women[edit]

The opioid epidemic affects women and men differently,[21] For instance, women are more likely than men to develop a substance use disorder. Women are also more likely to suffer chronic pain than men are.[22] There are also many more situations in which women are to receive pain medicine. In cases of domestic abuse and rape, women are prescribed pain medicine more than men.[22] Along with that during pregnancy women may use prescription opioids to help with pregnancy pain, especially with post-pregnancy pain.[22] Since women are more likely to be prescribed opioids, they are more likely to become addicted to these opioids which is what makes them a target to the opioid epidemic. The number of women that have died from opioid pain relievers has increased 5 times from what it was in 1999 in 2010.[23] To help stop the spread of opioid abuse in women, it is advised that women are educated on the drugs that they are taking and the possible risk of addiction. Additionally, alternatives should always be used when possible in order to prevent addiction.[22]

Adolescents[edit]

Teens are also another category of people that can become easily hooked on opioids. For teens the use of opioids usually does not start as a pain management drug, teens will engage in drugs as recreational drugs.[24] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says that for every opioid death of a teen there are 119 emergency visits and 22 treatment admissions related to opioid abuse.[24] Easy accessibility to these opioids is another reason why these drugs are becoming popular. If family members are taking opioids for pain or have taken them in the past and did not dispose of them correctly, it can make it easy for adolescents to get their hands on them.[24] Education on opioid use and opioid disorders is important to keep children away from these drugs.

Not only are youth at heightened risk of developing opioid addictions, but treating opioid use disorder in this population is also more difficult than it is for older individuals. A systematic review of the epidemiologic literature has found that adolescents and young adults consistently have shorter retention times in medication treatments for opioid use disorder than do older adults. [25]

Limited treatment[edit]

The continued prevalence of the opioid epidemic in the United States can be traced to many reasons. For one, there is a lack of appropriate treatments and treatment centers across the nation.[26] Big cities like New York City are lacking in treatment services and health offices as well as small rural areas.[26] Another reason that the opioid epidemic is hard to combat is that housing is limited to recovering addicts.[26] Having limited housing makes it easy for recovering opioid users to return to old environments that promote drug abuse. Along with housing, jobs for recovering addicts can be difficult to find as well. Addicts with criminal records are not able to find jobs once they leave recovery. Having to combat job insecurity can lead to stress, which can push someone to relapse.[26] The fact that “wraparound services”, or programs that provide services for patients that have just come out of rehabilitation centers[26], are non-existent is also a reason why the opioid epidemic has gone on for so long.

Public policy response[edit]

The public reaction that has made the first step in ending the opioid epidemic was the lawsuit that the state of Oklahoma put up against Purdue Pharma.[27] The state of Oklahoma argued that Purdue Pharma helped start the opioid epidemic because of assertive marketing and deceptive claims on the dangers of addiction.[28] One of the marketing strategies was to redefine “substance use disorder” as “pseudo addiction".[27] The Purdue Pharma agreed to settle and pay 270 million dollars to the state of Oklahoma that would go towards addiction research and treatment.[28] The settlement could indicate a win for other states that have taken legal action against similar opioid manufacturers.[27] Specifically, States like California are raising similar claims that Purdue Pharma market the drug Oxycontin as a safe and effective treatment, which led to the opioid crisis leaving thousands dead in California due to opioid overdoses.[29]

Canada[edit]

In 1993, an investigation by the chief coroner in British Columbia identified an “inordinately high number” of drug-related deaths, of which there were 330. By 2017, there were 1,473 deaths in British Columbia and 3,996 deaths in Canada as a whole.[30]

Canada followed the United States as the second highest per capita user of prescription opioids in 2015.[31] In Alberta, emergency department visits as a result of opiate overdose rose 1,000% in the previous five years. The Canadian Institute for Health Information found that while a third of overdoses were intentional overall, among those ages 15–24 nearly half were intentional.[32] In 2017 there were 3,987 opioid-related deaths in Canada, 92% of these deaths being unintentional. The number of deaths involving fentanyl or fentanyl analogues increased by 17% compared to 2016.[33]

North America's first safe injection site, Insite, opened in the Downtown Eastside (DTES) neighborhood of Vancouver in 2003. Safe injection sites are legally sanctioned, medically supervised facilities in which individuals are able to consume illicit recreational drugs, as part of a harm reduction approach towards drug problems which also includes information about drugs and basic health care, counseling, sterile injection equipment, treatment referrals, and access to medical staff, for instance in the event of an overdose. Health Canada has licensed 16 safe injection sites in the country.[34] In Canada, about half of overdoses resulting in hospitalization were accidental, while a third were deliberate overdoses.[32]

OxyContin was removed from the Canadian drug formulary in 2012[35] and medical opioid prescription was reduced, but this led to an increase in the illicit supply of stronger and more dangerous opioids such as fentanyl and carfentanil. In 2018 there were around 1 million users at risk from these toxic opioid products. In Vancouver Dr. Jane Buxton of the British Columbia Centre for Disease Control joined the Take-home naloxone program in 2012 to provide at risk individuals medication that quickly reverses the effects of an overdose from opioids.[36]

Outside North America[edit]

Approximately 80 percent of the global pharmaceutical opioid supply is consumed in the United States.[37] It has also become a serious problem outside the U.S., mostly among young adults.[38] The concern not only relates to the drugs themselves, but to the fact that in many countries doctors are less trained about drug addiction, both about its causes or treatment.[19] According to an epidemiologist at Columbia University: "Once pharmaceuticals start targeting other countries and make people feel like opioids are safe, we might see a spike [in opioid abuse]. It worked here. Why wouldn't it work elsewhere?"[19]

Most deaths worldwide from opioids and prescription drugs are from sexually transmitted infections passed through shared needles. This has led to a global initiative of needle exchange programs and research into the varying needle types carrying STIs. In Europe, prescription opioids accounted for three-quarters of overdose deaths among those between ages 15 and 39.[38] Some worry that the epidemic could become a worldwide pandemic if not curtailed.[19] Prescription drug abuse among teenagers in Canada, Australia, and Europe were comparable to U.S. teenagers.[19] In Lebanon and Saudi Arabia, and in parts of China, surveys found that one in ten students had used prescription painkillers for non-medical purposes. Similar high rates of non-medical use were found among the young throughout Europe, including Spain and the United Kingdom.[19]

While strong opiates are heavily regulated within the European Union, there is a "hidden addiction" with codeine. Codeine, though a mild painkiller, is converted into morphine in the liver.[39] "‘It’s a hidden addiction,’ said Dr Michael Bergin of Waterford Institute of Technology, Ireland. ‘Codeine abuse affects people with diverse profiles, from children to older people across all social classes.’"[39]

Myanmar[edit]

On 18 May 2020, Myanmar and the U.N. Office of Drugs and Crime (UNODC) announced that, over the previous three months, police had confiscated illicit drugs with a street value estimated at hundreds of millions of dollars. Most was methamphetamine; they also seized 3,750 liters (990 gallons) of liquid methylfentanyl that can be used to manufacture a synthetic opioid.[40]

United Kingdom[edit]

From January to August 2017, there were 60 fatal overdoses of fentanyl in the UK.[41] Opioid prescribing in English general practice mirrors general geographical health inequalities.[42] In July 2019 two Surrey GPs working for a Farnham-based online pharmacy were suspended by the General Medical Council for prescribing opioids online without appropriate safeguards.[43] Scotland has a drug mortality rate of 175 per million population aged 15 to 64, by far the worst in Europe.[44] Public Health England reported in September 2019 that half the patients using strong painkillers, antidepressants and sleeping tablets had been on them for more than a year, which was generally longer than was "clinically" appropriate and where the risks could outweigh the benefits. They found that problems in the UK were less than in most comparable countries,[45] but there were 4,359 deaths related to drug poisoning, largely opioids, in England and Wales in 2018 the highest number recorded since 1993.[46]

Public Health England reported in September 2019 that 11.5 million adults in England had been prescribed benzodiazepines, Z-drugs, gabapentinoids, opioids or antidepressants in the year ending March 2018. Half of these had been prescribed for at least a year. About 540,000 had been prescribed opioids coninously for 3 years or more. Prescribing of opioids and Z-drugs had decreased, but antidepressants and gabapentinoids had increased, gabapentinoids by 19% between 2015 and 2018 to around 1.5 million.[47]

Accessibility of prescribed opioids[edit]

The worry surrounding the potential of a worldwide pandemic has affected opioid accessibility in countries around the world. Approximately 25.5 million people per year, including 2.5 million children, die without pain relief worldwide, with many of these cases occurring in low and middle-income countries. The current disparity in accessibility to pain relief in various countries is significant. The U.S. produces or imports 30 times as much pain relief medication as it needs while low-income countries such as Nigeria receive less than 0.2% of what they need, and 90% of all the morphine in the world is used by the world's richest 10%.[48]

America's opioid epidemic has resulted in an “opiophobia” that is stirring conversations among some Western legislators and philanthropists about adopting a “war on drugs rhetoric” to oppose the idea of increasing opioid accessibility in other countries, in fear of starting similar opioid epidemics abroad.[49] The International Narcotics Control Board (INCB), a monitoring agency established by the U.N. to prevent addiction and ensure appropriate opioid availability for medical use, has written model laws limiting opioid accessibility that it encourages countries to enact. Many of these laws more significantly impact low-income countries; for instance, one model law ruled that only doctors could supply opioids, which limited opioid accessibility in poorer countries that had a scarce number of doctors.[50]

In 2018, deputy head of China's National Narcotics Commission Liu Yuejin criticized the U.S. market's role in driving opioid demand.[51]

In 2016, the medical news site STAT reported that while Mexican cartels are the main source of heroin smuggled into the U.S., Chinese suppliers provide both raw fentanyl and the machinery necessary for its production.[52] In British Columbia, police discovered a lab making 100,000 fentanyl pills each month, which they were shipping to Calgary, Alberta. 90 people in Calgary overdosed on the drug in 2015.[52] In Southern California, a home-operated drug lab with six pill presses was uncovered by federal agents; each machine was capable of producing thousands of pills an hour.[52]

In 2018 a woman died in London after getting a prescription for tramadol from an online doctor based in Prague who had not considered her medical history. Regulators in the UK admitted that there was nothing they could do to stop this happening again.[53] A reporter from The Times was able to buy opioids from five online pharmacies in September 2019 without any contact with their GP by filling in an online questionnaire and sending a photocopy of their passport.[54]

Alternative for opioids[edit]

Alternative drug options for opioids include ibuprofen, Tylenol, Aspirin and steroid options, all of which can be prescribed to patients or provided to them over the counter.[55] Along with drug alternatives, many other alternatives can provide relief through physical activities. Physical therapy, acupuncture, injections, nerve blocks, massages, and relaxation techniques are physical activities that have been found to help with chronic pain.[55] New pain management drugs like Marijuana and Cannabinoids have also been found to help treat symptoms of pain.[55] Many treatments like cancer treatments are using these drugs to help control pain.[55]

Signs of addiction[edit]

People that are addicted to opioids can have many changes in behavior. Some of the common signs or symptoms of addiction include spending more time alone, losing interest in activities, quickly changing moods, sleeping at odd hours, getting in trouble with the law, and financial hardships.[56] If you notice any of these behaviors in a peer or in oneself, a physician should be consulted with.[56]

See also[edit]

- Diseases of despair – including opioid overdose

References[edit]

- ^ "Opioids". Drugs of Abuse. National Institute on Drug Abuse. Retrieved July 29, 2019.

- ^ "Information sheet on opioid overdose". Management of Substance Abuse. World Health Organization. November 2014. Archived from the original on December 1, 2014.

The URL remains live, but the live version as of this writing is from August 2018. Recommend updating content and updating this citation.

The URL remains live, but the live version as of this writing is from August 2018. Recommend updating content and updating this citation.

- ^ Alexander GC, Kruszewski SP, Webster DW (2012). "Rethinking Opioid Prescribing to Protect Patient Safety and Public Health". JAMA. 308 (18): 1865–1866. doi:10.1001/jama.2012.14282. PMID 23150006.

- ^ a b Franklin, G. M. (September 29, 2014). "Opioids for chronic noncancer pain: A position paper of the American Academy of Neurology". Neurology. 83 (14): 1277–1284. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000000839. PMID 25267983.

- ^ Mohamadi A, Chan JJ, Lian J, Wright CL, Marin AM, Rodriguez EK, von Keudell A, Nazarian A (August 2018). "Risk Factors and Pooled Rate of Prolonged Opioid Use Following Trauma or Surgery: A Systematic Review and Meta-(Regression) Analysis". The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. American Volume. 100 (15): 1332–1340. doi:10.2106/JBJS.17.01239. PMID 30063596.(subscription required)

- ^ "Why opioid overdose deaths seem to happen in spurts", CNN, February 8, 2017

- ^ "Too many meds? America's love affair with prescription medication". Retrieved April 26, 2018.

- ^ "Pills for everything: The power of American pharmacy". Retrieved April 26, 2018.

- ^ Bekiempis V (April 9, 2012). "America's prescription drug addiction suggests a sick nation". The Guardian. Retrieved April 26, 2018.

- ^ "What are opioids and what are the risks?". BBC. March 19, 2018. Retrieved February 27, 2019.

- ^ a b "America’s opioid epidemic is worsening", the Economist (U.K.) March 6, 2017,

- ^ Baker DW (May 5, 2017). "The Joint Commission's Pain Standards: Origin and Evolution" (PDF). Oakbrook Terrace, IL: The Joint Commission.

- ^ "Facing Addiction in America" (PDF). U.S. Surgeon General. 2016. p. 413. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 19, 2017.

- ^ Alexander GC, Kruszewski SP, Webster DW (November 2012). "Rethinking opioid prescribing to protect patient safety and public health". JAMA. 308 (18): 1865–6. doi:10.1001/jama.2012.14282. PMID 23150006.

- ^ Shipton EA, Shipton EE, Shipton AJ (June 2018). "A Review of the Opioid Epidemic: What Do We Do About It?". Pain and Therapy. 7 (1): 23–36. doi:10.1007/s40122-018-0096-7. PMC 5993689. PMID 29623667.

- ^ Amos O (October 25, 2017). "Why opioids are such an American problem". BBC News. Retrieved December 29, 2017.

- ^ Erickson A (December 28, 2017). "Analysis | Opioid abuse in the U.S. is so bad it's lowering life expectancy. Why hasn't the epidemic hit other countries?". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved December 29, 2017.

- ^ Daubresse M, Chang HY, Yu Y, Viswanathan S, Shah ND, Stafford RS, Kruszewski SP, Alexander GC (October 2013). "Ambulatory diagnosis and treatment of nonmalignant pain in the United States, 2000-2010". Medical Care. 51 (10): 870–8. doi:10.1097/MLR.0b013e3182a95d86. PMC 3845222. PMID 24025657.

- ^ a b c d e f "The opioid epidemic could turn into a pandemic if we're not careful", Washington Post, February 9, 2017

- ^ "Opioid Prescriptions Fall After 2010 Peak, C.D.C. Report Finds", New York Times, July 6, 2017

- ^ Serdarevic, Mirsada (2017). "Gender differences in prescription opioid use". Current Opinion in Psychiatry. 30 (4): 238–246. doi:10.1097/YCO.0000000000000337. PMC 5675036. PMID 28426545.

- ^ a b c d "Women and Opioids". Rehab Spot.

- ^ Westphalen, Dena. "Healthline". Women and Opioids: The Unseen Impact.

- ^ a b c Bagley, Sarah. "Opioids and Adolescents". U.S. Department of Health & Human Services.

- ^ Viera, Adam; Bromberg, Daniel J; Whittaker, Shannon; Refsland, Bryan M; Stanojlović, Milena; Nyhan, Kate; Altice, Frederick L (2020). "Adherence to and Retention in Medications for Opioid Use Disorder among Adolescents and Young Adults". Epidemiologic Reviews. doi:10.1093/epirev/mxaa001.

- ^ a b c d e Strach, Patricia; Zuber, Katie; Elizabeth, Pérez-Chiqués. "How a Rural Community Addresses the Opioid Crisis" (PDF). Rockefeller Institute of Government.

- ^ a b c Santhanam, Laura. "What Purdue Pharma's settlement with Oklahoma means for the opioid crisis". PBS.

- ^ a b Bebinger, Martha. "Purdue Pharma Agrees To $270 Million Opioid Settlement With Oklahoma". NPR.

- ^ MCGREEVY, PATRICK. "California joins opioid fight, sues Purdue Pharma over marketing of OxyContin". LA Times.

- ^ Fischer, Benedict; et al. (February 1, 2019). "The opioid death crisis in Canada: crucial lessons for public health". Lancet. 4 (2): e81–e82. doi:10.1016/S2468-2667(18)30232-9. PMID 30579840. Retrieved March 30, 2019.

- ^ Dyer, Owen (September 3, 2015). "Canada's prescription opioid epidemic grows despite tamperproof pills". BMJ. 351: h4725. doi:10.1136/bmj.h4725. ISSN 1756-1833. PMID 26338104.

- ^ a b "Canada's opioid crisis is burdening the health care system, report warns". Globalnews.ca. September 14, 2017. Retrieved November 10, 2017.

- ^ Canada, Public Health Agency of; Canada, Public Health Agency of (June 19, 2018). "National report: Apparent opioid-related deaths in Canada". aem. Retrieved November 20, 2018.

- ^ Levinson-King R (August 7, 2017). "The city where addicts are allowed to inject". BBC News. Retrieved November 10, 2017.

- ^ Morin KA, Eibl JK, Franklyn AM, Marsh DC (November 2017). "The opioid crisis: past, present and future policy climate in Ontario, Canada". Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy. 12 (1): 45. doi:10.1186/s13011-017-0130-5. PMC 5667516. PMID 29096653.g

- ^ "Distribution of take-home opioid antagonist kits during a synthetic opioid epidemic in British Columbia, Canada: a modelling study". Lancet. April 17, 2018. Retrieved August 30, 2019.

- ^ "Americans consume vast majority of the world's opioids", Dina Gusovsky, CNBC, April 27, 2016

- ^ a b Martins SS, Ghandour LA (February 2017). "Nonmedical use of prescription drugs in adolescents and young adults: not just a Western phenomenon". World Psychiatry. 16 (1): 102–104. doi:10.1002/wps.20350. PMC 5269500. PMID 28127929.

- ^ a b "Europe's silent opioid epidemic". Horizon: the EU Research & Innovation magazine. Retrieved May 6, 2019.

- ^ Berlinger, Joshua (May 18, 2020). "Drug bust in Myanmar nets haul likely worth hundreds of millions of dollars". CNN. Retrieved May 18, 2020.

- ^ "Warnings after drug kills 'at least 60'". BBC News. August 1, 2017. Retrieved November 10, 2017.

- ^ "Opioid prescribing highest in more deprived regions of England, study shows". Pharmaceutical Journal. January 16, 2019. Retrieved February 27, 2019.

- ^ "Surrey GPs suspended for prescribing opioids online without appropriate safeguards". Surrey Live. August 1, 2019. Retrieved August 30, 2019.

- ^ "Task force to fight drugs death epidemic as Daily Record sparks Scottish Government into action". Daily Record. March 30, 2019. Retrieved March 31, 2019.

- ^ "Too many hooked on prescription drugs - health chiefs". BBC. September 10, 2019. Retrieved September 10, 2019.

- ^ "Drug-related deaths in England and Wales reach record levels, says ONS". Pharmaceutical Journal. August 16, 2019. Retrieved October 1, 2019.

- ^ "More than 500,000 patients in England were prescribed an opioid for over three years, PHE finds". Pharmaceutical Journal. September 10, 2019. Retrieved November 3, 2019.

- ^ Knaul FM, Farmer PE, Krakauer EL, De Lima L, Bhadelia A, Jiang Kwete X, Arreola-Ornelas H, Gómez-Dantés O, Rodriguez NM, Alleyne GA, Connor SR, Hunter DJ, Lohman D, Radbruch L, Del Rocío Sáenz Madrigal M, Atun R, Foley KM, Frenk J, Jamison DT, Rajagopal MR (April 2018). "Alleviating the access abyss in palliative care and pain relief-an imperative of universal health coverage: the Lancet Commission report". Lancet. 391 (10128): 1391–1454. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32513-8. PMID 29032993.

- ^ McNeil DG (December 4, 2017). "'Opiophobia' Has Left Africa in Agony". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 27, 2018.

- ^ The Conversation US (March 25, 2016). "The Other Opioid Crisis – People in Poor Countries Can't Get the Pain Medication They Need". Huffington Post. Retrieved April 27, 2018.

- ^ "China says United States domestic opioid market the crux of crisis". Reuters. June 25, 2018. Retrieved June 28, 2018.

- ^ a b c "'Truly terrifying': Chinese suppliers flood US and Canada with deadly fentanyl", STAT, April 5, 2016,

- ^ "Steve Field: Digital GPs overseas remain a danger". Health Service Journal. March 8, 2019. Retrieved April 15, 2019.

- ^ "RPS calls for investigation after online pharmacies prescribed opioids to undercover reporter". Pharmaceutical Journal. October 1, 2019. Retrieved November 20, 2019.

- ^ a b c d "Non-Opioid Treatment". American Society of Anesthesiologists.

- ^ a b "Opioid Abuse". American Society of Anesthesiologists.