Shanty town

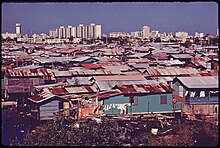

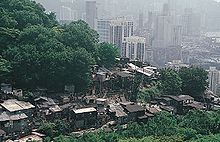

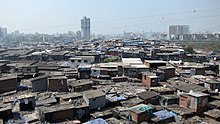

A shanty town or squatter area is a settlement of improvised buildings known as shanties or shacks, typically made of plywood, corrugated metal, sheets of plastic, and cardboard boxes. Sometimes called a squatter, or spontaneous settlement, a typical shanty town often lacks adequate infrastructure, including proper sanitation, safe water supply, electricity, street drainage, or other basic necessities of human settlement. These are the autonomous, self-help housing developments created by low- and very low-income individuals and families around the world.[1]

Shanty towns are mostly found in developing nations, but also in some parts of developed nations.[2][3][4] They are usually on the periphery of cities, in public parks, or near railroad tracks, rivers, lagoons or city trash dump sites.

Features[edit]

Since construction is informal and unguided by urban planning, there is typically no formal street grid, house numbers, or named streets. Such settlements also lack some or all basic public services such as a sewage network, electricity, safe running water, rain water drainage, garbage removal, access to public transport, or insect and disease control services. Even if these resources are present, they are likely to be disorganized, unreliable, and poorly maintained.

Shanty towns also tend to lack basic services present in more formally organized settlements, including policing, mail delivery, medical services, and fire fighting. Fires are a particular danger for shanty towns not only for the lack of fire fighting stations and the difficulty fire trucks have traversing the settlement in the absence of formal street grids,[5] but also because of the high density of buildings and flammability of materials used in construction.[6] A sweeping fire on the hills of Shek Kip Mei, Hong Kong, in late 1953 left 53,000 dwellers homeless, prompting the colonial government to institute a resettlement estate system.

Shanty towns have high rates of crime, suicide, drug use, and disease. However, Swiss journalist Georg Gerster has noted (with specific reference to the invasões of Brasilia) that "squatter settlements [as opposed to slums], despite their unattractive building materials, may also be places of hope, scenes of a counter-culture, with an encouraging potential for change and a strong upward impetus".[7] Stewart Brand has also written, more recently, that "squatter cities are Green. They have maximum density—a million people per square mile in Mumbai—and minimum energy and material use. People get around by foot, bicycle, rickshaw, or the universal shared taxi ... Not everything is efficient in the slums, though. In the Brazilian favelas where electricity is stolen and therefore free, Jan Chipchase from Nokia found that people leave their lights on all day. In most slums recycling is literally a way of life." (2010)[8]

Etymology[edit]

Shanty is probably from Canadian French chantier, a winter station established for the organization of lumberjacks.[9]

Another possible derivation is from the Irish language sean tí meaning old house.

Hutment means an "encampment of huts". When the term is used by the military, it means "temporary living quarters specially built by the army for soldiers".[10] The term is also a synonym for shanty town, particularly in developing countries.

Development[edit]

While most shanty towns begin as precarious establishments haphazardly thrown together without basic social and civil services, over time, some have undergone a certain amount of development. Often the residents themselves are responsible for the major improvements.[11] Community organizations sometimes working alongside NGOs, private companies, and the government, set up connections to the municipal water supply, pave roads, and build local schools.[11] Some of these shanties have become middle class suburbs. One such extreme example is the Los Olivos Neighborhood of Lima, Peru. Chameh is, one of Lima's largest, along with gated communities, casinos, and even plastic surgery clinics, are just a few of many developments that have transformed what used to be a decrepit shanty.[11] A few Brazilian favelas have also seen improvements in recent years, enough so to attract tourists who flock to catch a glimpse of the colorful lifestyle perched atop Rio de Janeiro's highlands.[12] Development occurs over a long period of time and newer towns still lack basic services. Nevertheless, there has been a general trend whereby shanties undergo gradual improvements, rather than relocation to even more distant parts of a metropolis and replacement by gated communities constructed over their ruins.[13] Many shanty towns are starting to implement the use of composting toilets[14] and solar panels,[15] and many of the people living in slums may have access to cell phones and even the internet.[16] However, in spite of all this, inequality associated with shanty towns has only increased over time.[17]

Regional names[edit]

- Asentamientos in Guatemala

- Baraccopoli or also Bidonville in Italy

- Barrios de invasión in Colombia

- Beiliang, Donghe District, Baotou, Inner Mongolia autonomous region in China[18]

- Bidonvilles in France

- Campamentos or poblaciones callampa in Chile.

- Cantegriles (or, more recently, Asentamientos) in Uruguay

- Chabolas in Spain

- Colonias or "Migrant camps" on the Mexico–United States border

- Favelas in Brazil

- Gecekondu in Turkey

- Ghetto in Panama

- Gueto in Puerto Rico

- Hoovervilles in the United States (historical)

- Invasiones in Colombia and Ecuador

- Karton Siti in Serbia

- Llegaipón in Cuba

- Location in Namibia[19]

- Malin Basti or Zopadpatti in India

- Paraggoupoli in Greece

- Perkampungan Kumuh (literally means 'seedy settlement') in Indonesia

- Pueblos jóvenes (young towns) or barriadas in Peru

- Putri in Hungary

- Mahalále in Romania

- Ranchos in Venezuela

- Squatter's Area in the Philippines

- Гетто (Ghetto) or Шанхай (Shanghai) in Soviet Union and Russian Federation[20]

- Tent cities and Trailer parks in the United States

- Township in South Africa[19]

- Tugurios or precarios in Costa Rica

- Villas miseria or just villas in Argentina

- Zona marginal or ciudad perdida in Mexico

- al-Sakan al-Ashawayie (السكن العشوائي) in Syria

- l-Karyān (لكاريان) or more formally Door a-Ssafiih (دور الصفيح) (Tin houses) in Morocco

- Гето in Bulgaria[21][circular reference]

Specific places[edit]

- Cité Soleil (Haiti)

- Ciudad Bolívar, Bogotá (Bogotá, Colombia)

- Dharavi (India)

- Joe Slovo (Cape Town, South Africa)

- Khayelitsha (Cape Town, South Africa)

- Kibera (Nairobi, Kenya)

- Kya Sands (Johannesburg, South Africa)

- Mathare (Nairobi, Kenya)

- Rocinha (Rio de Janeiro, Brazil)

- Tondo (Manila, Philippines)

- see also List of favelas in Brazil

People and organizations[edit]

- Abahlali baseMjondolo (South Africa)

- Akhtar Hameed Khan

- CEIFAR

- Hernando de Soto (economist)

- Marie Huchzermeyer (scholar)

- Mike Davis (scholar)

- Chinese New Village (Malaysia)

- Orangi Pilot Project

- Slum Dwellers International

- Slum upgrading

- The Susso, welfare in Australia originating in the Great Depression

- United Nations Human Settlements Programme

- Western Cape Anti-Eviction Campaign

Related concepts[edit]

- Displaced persons camp

- Dormitory

- Favela

- Flophouse

- Ghetto

- Hobo

- Refugee shelter

- Skid row

- Slumlord

- Squatting

- Tent city

- Trailer park

- Urban decay

Examples[edit]

Developed countries[edit]

Although shanty towns are less common in developed countries, there are some cities that have them. While shanty towns are less common in Europe, the growing influx of immigrants have fueled shantytowns in cities commonly used as a point of entry into the EU, including Athens and Patras in Greece.[22] In Madrid, Spain, a low-class neighborhood named Cañada Real (which is considered a shanty town) has no formal education system, professional nurseries or modern health clinics and is considered the largest slum in Europe.[23] In Portugal, shanty towns known as "barracas" or "bairros de lata" are made up of immigrants from former Portuguese African colonies and Roma from Eastern Europe. Most of them are located in Lisbon metropolitan area. In the United States, some cities such as Newark and Oakland have witnessed the creation of tent cities. Other settlements in developed countries that are comparable to shanty towns include the Colonias near the border with Mexico, and bidonvilles in France, which may exist in the peripheries of some cities.

In some cases, shanty towns can persist in gentrified areas that local governments have yet to redevelop, or in regions of political dispute. Examples of this include Ras Khamis in Israel and the Kowloon Walled City in Hong Kong.

Developing countries[edit]

Shanty towns are present in a number of countries. The largest shanty town in Asia is Orangi in Karachi, Pakistan, although at 22 square miles in size, it is “significantly less dense than most urban slums and also more structured” - in comparison, Asia’s next largest shanty town, Dharavi in Mumbai is home to one million people in about one square mile.[24] In francophone countries, shanty towns are referred to as bidonvilles (French for "can town" - can being a reference to tin metal); such countries include Tunisia and Haiti. Other countries with shanty towns include South Africa (where they are often called Townships) or Imijondolo, Kenya (including the Kibera and Mathare slums), the Philippines (often called squatter areas), Venezuela (where they are known as barrios), Brazil (favelas), Argentina (villas miseria), West Indies such as Jamaica and Trinidad and Tobago (where they are known as shanty towns), and Peru (where they are known as "young towns"). There is also a major shanty town population in countries such as Bangladesh,[25] and the People's Republic of China.[26][27][28]

In popular culture[edit]

- The 1985 film Police Story starts off in a shanty town.

- The 1988 film They Live, the title character is taken to a shanty town at the beginning of the film, which is subsequently destroyed.

- The film Slumdog Millionaire centres around characters who spend most of their lives in Indian shanty towns.

- In Timothy of the Cay, Theodore Taylor's follow-up to his 1969 book The Cay, the boyhood home of the character of Timothy, called "Back o' All," is the poorest district of Charlotte Amalie, which was a shanty town on the Virgin Island of St. Thomas for an unspecified number of generations.

- The South African film District 9 is largely set in (and takes its name from) a fictional Johannesburg township.

- The Brazilian films City of God (set in Cidade de Deus) and Tropa de Elite - and to a lesser extent its sequel, Elite Squad: The Enemy Within - are all largely set in favela shanty towns in Rio de Janeiro, as are the semi-autobiographical novels on which they are based (City of God and Elite da Tropa).

- One of the alternate titles for Demented Death Farm Massacre is Shantytown Honeymoon.

- One of the areas in Resident Evil 5 is located in a shanty town.

- Some of the second half of Max Payne 3 takes place in Nova Esperança, a fictional favela in the city of São Paulo, Brazil.

- One of the sections of the 2013 Tomb Raider video game is located in a shanty town, as part of the single player campaign, and also on one of the multiplayer levels.

- Many of the cities and camps in the Fallout series are shanty towns. Some settlements consist of hastily repaired buildings whilst others are entirely cobbled-together of scrap materials.

- Reggae singer Desmond Dekker sang a song called "007 (Shanty Town)".

- Kibera Kid is an award-winning short film by Nathan Collett set in the Kibera slums of Nairobi, Kenya.

- White Elephant, 2012 Argentinian movie, is set in a villa miseria in Buenos Aires, Argentina

- Miracle in Milan is a 1951 Italian film told as a neo-realist fable of the lives of a poverty-stricken group in post-war Milan, Italy.

- One of the chapters of the Left 4 Dead 2 campaign Swamp Fever, set in a Louisiana bayou village, is called The Shantytown and takes place in a series of patchwork wooden buildings not uncommon for shanty towns.

- The 2016 Chinese TV series Housing tells story of shantytown clearance in Beiliang, Baotou, Inner Mongolia, China.

- Fast Five involves a chase through a shanty town

- In the video game Fortnite: Battle Royale, there is a shanty town in a swamp in the southwest part of the island where the game takes place.

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ Caves, R. W. (2004). Encyclopedia of the City. Routledge. p. 626. ISBN 9780415252256.

- ^ a b What America Looked Like: Puerto Rican Slums in the Early 1970s The Atlantic (July 17, 2012)

- ^ Nick Squires and Paul Anast, "Greek immigration crisis spawns shanty towns and squats", The Telegraph, (September 7, 2009).

- ^ Showdown Looms Over Europe's Largest Shantytown LAUREN FRAYER, National Public Radio (Washington DC), April 27, 2012.

- ^ Jorge Hernández. "Sólo tres unidades de bomberos atienden 2 mil barrios de Petare" (in Spanish).

- ^ See the report on shack fires in South Africa by Matt Birkinshaw [1] as well as the wider collection of articles in fires in shanty towns at [2]

- ^ Georg Gerster, Flights of Discovery: The Earth from Above, 1978, London: Paddington, p. 116.

- ^ Stewart Brand, "Stewart Brand on New Urbanism and squatter communities", The New Urban Network, reprinted from Whole Earth Discipline, Penguin.

- ^ Oxford English Dictionary Online

- ^ "Hutment". Free Dictionary. Retrieved April 6, 2013.

- ^ a b c "Some "Young Towns" in Lima Not So Young Anymore". COHA Staff. Archived from the original on 23 August 2011. Retrieved 23 July 2015.

- ^ Clarke, Felicity (May 16, 2011). "Favela Tourism Provides Entrepreneurial Opportunities in Rio". Forbes.

- ^ "Informality: Re-Viewing Latin American Cities". Retrieved 23 July 2015.

- ^ Thomson Reuters Foundation. "Thomson Reuters Foundation". Archived from the original on 16 April 2013. Retrieved 23 July 2015.

- ^ "Youth Bring Low-Cost Solar Panels to Kenyan Slum". Retrieved 23 July 2015.

- ^ "IT for schools, Schools, Education, Technology, UK news, Online learning e-learning (Education)". The Guardian. London. May 8, 2001.

- ^ "UN study says wealth gap in Latin America increases- A study by the United Nations suggests the gap between the rich and the poor in much of Latin America is widening". BBC News. August 21, 2012. Retrieved 6 January 2013.

- ^ Housing tells story of shantytown clearence [sic] Chinadaily 2016-10-17

- ^ a b "Dictionary: location". Oxford Living Dictionaries. Oxford University Press.

- ^ http://cheloveknauka.com/kvazionimy-v-russkom-argo

- ^ bg:Гето

- ^ Squires, Nick; Anast, Paul (September 7, 2009). "Greek immigration crisis spawns shanty towns and squats". The Daily Telegraph. London.

- ^ Fotheringham, Alasdair (November 27, 2011). "In Spain's heart, a slum to shame Europe". The Independent. London.

- ^ 5 biggest slums in the world Daniel Tovrov, IB Times (December 9, 2011)

- ^ "ISUH home" (PDF). Retrieved 23 July 2015.

- ^ Demolitions limit slum villages to city outskirts. Archived 2009-05-02 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "People's Daily Online -- "Slums" sting Chinese cities, hamper building of harmonious society". Retrieved 23 July 2015.

- ^ Jane Kelly, Review: Planet of Slums, by Mike Davis, Verso, 2006, £15.99. Socialist Outlook: SO/10 - Summer 2006. Archived 2009-01-12 at the Wayback Machine

Further reading[edit]

- Daniel Carter Beard (1920). Shelters, shacks, and shanties. C. Scribner's Sons. Retrieved 24 August 2012.

- Slate article about an economist proposing New Orleans to be reconstructed with shanties

External links[edit]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Shanty towns. |