Silurian

| Silurian Period 443.8–419.2 million years ago | |

Plate tectonics of Earth during Early Silurian period | |

| Mean atmospheric O 2 content over period duration |

c. 14 vol % (70 % of modern level) |

| Mean atmospheric CO 2 content over period duration |

c. 4500 ppm (16 times pre-industrial level) |

| Mean surface temperature over period duration | c. 17 °C (3 °C above modern level) |

| Sea level (above present day) | Around 180m, with short-term negative excursions[1] |

Epochs in the Silurian -444 — – -442 — – -440 — – -438 — – -436 — – -434 — – -432 — – -430 — – -428 — – -426 — – -424 — – -422 — – -420 — – -418 — Epochs of the Silurian Period. Axis scale: millions of years ago. | |

The Silurian (/sɪˈljʊər.i.ən, saɪ-/ sih-LYOOR-ee-ən, sy-)[4][5] is a geologic period and system spanning 24.6 million years from the end of the Ordovician Period, at 443.8 million years ago (Mya), to the beginning of the Devonian Period, 419.2 Mya.[6] The Silurian is the shortest period of the Paleozoic Era. As with other geologic periods, the rock beds that define the period's start and end are well identified, but the exact dates are uncertain by a few million years. The base of the Silurian is set at a series of major Ordovician–Silurian extinction events when up to 60% of marine genera were wiped out.

A significant evolutionary milestone during the Silurian was the diversification of jawed fish and bony fish. Multi-cellular life also began to appear on land in the form of small, bryophyte-like and vascular plants that grew beside lakes, streams, and coastlines, and terrestrial arthropods are also first found on land during the Silurian. However, terrestrial life would not greatly diversify and affect the landscape until the Devonian.

History of study[edit]

The Silurian system was first identified by British geologist Roderick Murchison, who was examining fossil-bearing sedimentary rock strata in south Wales in the early 1830s. He named the sequences for a Celtic tribe of Wales, the Silures, inspired by his friend Adam Sedgwick, who had named the period of his study the Cambrian, from the Latin name for Wales.[7] This naming does not indicate any correlation between the occurrence of the Silurian rocks and the land inhabited by the Silures (cf. Geologic map of Wales, Map of pre-Roman tribes of Wales). In 1835 the two men presented a joint paper, under the title On the Silurian and Cambrian Systems, Exhibiting the Order in which the Older Sedimentary Strata Succeed each other in England and Wales, which was the germ of the modern geological time scale.[8] As it was first identified, the "Silurian" series when traced farther afield quickly came to overlap Sedgwick's "Cambrian" sequence, however, provoking furious disagreements that ended the friendship.

Charles Lapworth resolved the conflict by defining a new Ordovician system including the contested beds.[9] An alternative name for the Silurian was "Gotlandian" after the strata of the Baltic island of Gotland.[10]

The French geologist Joachim Barrande, building on Murchison's work, used the term Silurian in a more comprehensive sense than was justified by subsequent knowledge. He divided the Silurian rocks of Bohemia into eight stages.[11] His interpretation was questioned in 1854 by Edward Forbes,[12] and the later stages of Barrande; F, G and H have since been shown to be Devonian. Despite these modifications in the original groupings of the strata, it is recognized that Barrande established Bohemia as a classic ground for the study of the earliest Silurian fossils.

Subdivisions[edit]

Llandovery[edit]

The Llandovery Epoch lasted from 443.8 ± 1.5 to 433.4 ± 2.8 mya, and is subdivided into three stages: the Rhuddanian,[13] lasting until 440.8 million years ago, the Aeronian, lasting to 438.5 million years ago, and the Telychian. The epoch is named for the town of Llandovery in Carmarthenshire, Wales.

Wenlock[edit]

The Wenlock, which lasted from 433.4 ± 1.5 to 427.4 ± 2.8 mya, is subdivided into the Sheinwoodian (to 430.5 million years ago) and Homerian ages. It is named after Wenlock Edge in Shropshire, England. During the Wenlock, the oldest-known tracheophytes of the genus Cooksonia, appear. The complexity of slightly later Gondwana plants like Baragwanathia, which resembled a modern clubmoss, indicates a much longer history for vascular plants, extending into the early Silurian or even Ordovician.[citation needed] The first terrestrial animals also appear in the Wenlock, represented by air-breathing millipedes from Scotland.[14]

Ludlow[edit]

The Ludlow lasted from 427.4 ± 1.5 to 423 ± 2.8 mya. It is named for the town of Ludlow in Shropshire, England. The Ludlow comprises the Gorstian stage (lasting until 425.6 million years ago) and the Ludfordian stage (named for Ludford, also in Shropshire).

Přídolí [edit]

The Přídolí epoch, lasting from 423 ± 1.5 to 419.2 ± 2.8 mya, is the final and shortest epoch of the Silurian. It is named after one locality at the Homolka a Přídolí nature reserve near the Prague suburb Slivenec in the Czech Republic. Přídolí is the old name of a cadastral field area.[15]

Regional stages[edit]

In North America a different suite of regional stages is sometimes used:

- Cayugan (Late Silurian – Ludlow)

- Lockportian (Middle Silurian: late Wenlock)

- Tonawandan (Middle Silurian: early Wenlock)

- Ontarian (Early Silurian: late Llandovery)

- Alexandrian (Earliest Silurian: early Llandovery)

In Estonia the following suite of regional stages is used:[16]

- Ohessaare stage (Late Silurian – early Přídolí)

- Kaugatuma stage (Late Silurian – late Přídolí)

- Kuressaare stage (Late Silurian – late Ludlow)

- Paadla stage (Late Silurian – early Ludlow)

- Rootsiküla stage (Middle Silurian: late Wenlock)

- Jaagarahu stage (Middle Silurian: middle Wenlock)

- Jaani stage (Middle Silurian: early Wenlock)

- Adavere stage (Early Silurian: late Llandovery)

- Raikküla stage (Early Silurian: middle Llandovery)

- Juuru stage (Earliest Silurian: early Llandovery)

Paleogeography[edit]

With the supercontinent Gondwana covering the equator and much of the southern hemisphere, a large ocean occupied most of the northern half of the globe.[17] The high sea levels of the Silurian and the relatively flat land (with few significant mountain belts) resulted in a number of island chains, and thus a rich diversity of environmental settings.[17]

During the Silurian, Gondwana continued a slow southward drift to high southern latitudes, but there is evidence that the Silurian icecaps were less extensive than those of the late-Ordovician glaciation. The southern continents remained united during this period. The melting of icecaps and glaciers contributed to a rise in sea level, recognizable from the fact that Silurian sediments overlie eroded Ordovician sediments, forming an unconformity. The continents of Avalonia, Baltica, and Laurentia drifted together near the equator, starting the formation of a second supercontinent known as Euramerica.

When the proto-Europe collided with North America, the collision folded coastal sediments that had been accumulating since the Cambrian off the east coast of North America and the west coast of Europe. This event is the Caledonian orogeny, a spate of mountain building that stretched from New York State through conjoined Europe and Greenland to Norway. At the end of the Silurian, sea levels dropped again, leaving telltale basins of evaporites extending from Michigan to West Virginia, and the new mountain ranges were rapidly eroded. The Teays River, flowing into the shallow mid-continental sea, eroded Ordovician Period strata, forming deposits of Silurian strata in northern Ohio and Indiana.

The vast ocean of Panthalassa covered most of the northern hemisphere. Other minor oceans include two phases of the Tethys, the Proto-Tethys and Paleo-Tethys, the Rheic Ocean, the Iapetus Ocean (a narrow seaway between Avalonia and Laurentia), and the newly formed Ural Ocean.

Climate and sea level[edit]

The Silurian period enjoyed relatively stable and warm temperatures, in contrast with the extreme glaciations of the Ordovician before it, and the extreme heat of the ensuing Devonian.[17] Sea levels rose from their Hirnantian low throughout the first half of the Silurian; they subsequently fell throughout the rest of the period, although smaller scale patterns are superimposed on this general trend; fifteen high-stands can be identified, and the highest Silurian sea level was probably around 140 m higher than the lowest level reached.[17]

During this period, the Earth entered a long, warm greenhouse phase, supported by high CO2 levels of 4500 ppm, and warm shallow seas covered much of the equatorial land masses. Early in the Silurian, glaciers retreated back into the South Pole until they almost disappeared in the middle of Silurian. The period witnessed a relative stabilization of the Earth's general climate, ending the previous pattern of erratic climatic fluctuations. Layers of broken shells (called coquina) provide strong evidence of a climate dominated by violent storms generated then as now by warm sea surfaces. Later in the Silurian, the climate cooled slightly, but closer to the Silurian-Devonian boundary, the climate became warmer.[citation needed]

Perturbations[edit]

The climate and carbon cycle appear to be rather unsettled during the Silurian, which had a higher concentration of isotopic excursions[clarification needed] than any other period.[17] The Ireviken event, Mulde event and Lau event each represent isotopic excursions following a minor mass extinction[18] and associated with rapid sea-level change, in addition to the larger extinction at the end of the Silurian.[17] Each one leaves a similar signature in the geological record, both geochemically and biologically; pelagic (free-swimming) organisms were particularly hard hit, as were brachiopods, corals and trilobites, and extinctions rarely occur in a rapid series of fast bursts.[17]

Flora and fauna[edit]

The Silurian was the first period to see megafossils of extensive terrestrial biota, in the form of moss-like miniature forests along lakes and streams. However, the land fauna did not have a major impact on the Earth until it diversified in the Devonian.[17]

The first fossil records of vascular plants, that is, land plants with tissues that carry water and food, appeared in the second half of the Silurian period.[19] The earliest-known representatives of this group are Cooksonia. Most of the sediments containing Cooksonia are marine in nature. Preferred habitats were likely along rivers and streams. Baragwanathia appears to be almost as old, dating to the early Ludlow (420 million years) and has branching stems and needle-like leaves of 10–20 cm. The plant shows a high degree of development in relation to the age of its fossil remains. Fossils of this plant have been recorded in Australia,[20] Canada[21] and China.[22] Eohostimella heathana is an early, probably terrestrial, "plant" known from compression fossils[23] of early Silurian (Llandovery) age.[24] The chemistry of its fossils is similar to that of fossilised vascular plants, rather than algae.[23]

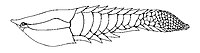

The first bony fish, the Osteichthyes, appeared, represented by the Acanthodians covered with bony scales; fish reached considerable diversity and developed movable jaws, adapted from the supports of the front two or three gill arches. A diverse fauna of eurypterids (sea scorpions)—some of them several meters in length—prowled the shallow Silurian seas of North America; many of their fossils have been found in New York state. Leeches also made their appearance during the Silurian Period. Brachiopods, bryozoa, molluscs, hederelloids, tentaculitoids, crinoids and trilobites were abundant and diverse.[citation needed] Endobiotic symbionts were common in the corals and stromatoporoids.[25][26]

Reef abundance was patchy; sometimes fossils are frequent but at other points are virtually absent from the rock record.[17]

The earliest-known animals fully adapted to terrestrial conditions appear during the Mid-Silurian, including the millipede Pneumodesmus.[14] Some evidence also suggests the presence of predatory trigonotarbid arachnoids and myriapods in Late Silurian facies.[27] Predatory invertebrates would indicate that simple food webs were in place that included non-predatory prey animals. Extrapolating back from Early Devonian biota, Andrew Jeram et al. in 1990[28] suggested a food web based on as-yet-undiscovered detritivores and grazers on micro-organisms.[29]

Eurypterus, a common Upper Silurian eurypterid

Notes[edit]

- ^ Haq, B. U.; Schutter, SR (2008). "A Chronology of Paleozoic Sea-Level Changes". Science. 322 (5898): 64–68. Bibcode:2008Sci...322...64H. doi:10.1126/science.1161648. PMID 18832639.

- ^ Jeppsson, L.; Calner, M. (2007). "The Silurian Mulde Event and a scenario for secundo—secundo events". Earth and Environmental Science Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh. 93 (02): 135–154. doi:10.1017/S0263593300000377.

- ^ Munnecke, A.; Samtleben, C.; Bickert, T. (2003). "The Ireviken Event in the lower Silurian of Gotland, Sweden-relation to similar Palaeozoic and Proterozoic events". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 195 (1): 99–124. doi:10.1016/S0031-0182(03)00304-3.

- ^ Wells, John (3 April 2008). Longman Pronunciation Dictionary (3rd ed.). Pearson Longman. ISBN 978-1-4058-8118-0.

- ^ "Silurian". Dictionary.com Unabridged. Random House.

- ^ "International Chronostratigraphic Chart v.2015/01" (PDF). International Commission on Stratigraphy. January 2015.

- ^ See:

- Murchison, Roderick Impey (1835). "On the Silurian system of rocks". Philosophical Magazine. 3rd series. 7: 46–52. From p. 48: " … I venture to suggest, that as the great mass of rocks in question, trending from south-west to north-east, traverses the kingdom of our ancestors the Silures, the term "Silurian system" should be adopted … "

- Wilmarth, Mary Grace (1925). Bulletin 769: The Geologic Time Classification of the United States Geological Survey Compared With Other Classifications, accompanied by the original definitions of era, period and epoch terms. Washington, D.C., U.S.A.: U.S. Government Printing Office. p. 80.

- ^ Sedgwick; Murchison, R.I. (1835). "On the Silurian and Cambrian systems, exhibiting the order in which the older sedimentary strata succeed each other in England and Wales". Report of the Fifth Meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science. § Notices and Abstracts of Miscellaneous Communications to the Sections. 5: 59–61.

- ^ Lapworth, Charles (1879). "On the tripartite classification of the Lower Palaeozoic rocks". Geological Magazine. 2nd series. 6: 1–15. From pp. 13–14: "North Wales itself – at all events the whole of the great Bala district where Sedgwick first worked out the physical succession among the rocks of the intermediate or so-called Upper Cambrian or Lower Silurian system; and in all probability much of the Shelve and the Caradoc area, whence Murchison first published its distinctive fossils – lay within the territory of the Ordovices; … Here, then, have we the hint for the appropriate title for the central system of the Lower Palaeozoics. It should be called the Ordovician System, after this old British tribe."

- ^ The Gotlandian system was proposed in 1893 by the French geologist Albert Auguste Cochon de Lapparent (1839–1908): Lapparent, A. de (1893). Traité de Géologie (in French). vol. 2 (3rd ed.). Paris, France: F. Savy. p. 748. From p. 748: "D'accord avec ces divisions, on distingue communément dans le silurien trois étages: l'étage inférieur ou cambrien (1) ; l'étage moyen ou ordovicien (2) ; l'étage supérieur ou gothlandien (3)." (In agreement with these divisions, one generally distinguishes, within the Silurian, three stages: the lower stage or Cambrian [1]; the middle stage or Ordovician [2]; the upper stage or Gotlandian [3].)

- ^ Barrande, Joachim (1852). Systême silurien du centre de la Bohême (in French). Paris, France and Prague, (Czech Republic): (Self-published). pp. ix–x.

- ^ Forbes, Edward (1854). "Anniversary Address of the President". Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society of London. 10: xxii–lxxxi. See p. xxxiv.

- ^ Named for the Cefn-Rhuddan Farm in the Llandovery area.

- ^ a b Paul Selden & Helen Read (2008). "The oldest land animals: Silurian millipedes from Scotland" (PDF). Bulletin of the British Myriapod & Isopod Group. 23: 36–37.

- ^ Manda, Štěpán; Frýda, Jiří (2010). "Silurian-Devonian boundary events and their influence on cephalopod evolution: evolutionary significance of cephalopod egg size during mass extinctions". Bulletin of Geosciences. 85 (3): 513–40. doi:10.3140/bull.geosci.1174.

- ^ "SILURIAN STRATIGRAPHY OF ESTONIA 2015" (PDF). Stratigraafia.info. Retrieved 3 February 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Munnecke, Axel; Calner, Mikael; Harper, David A.T.; Servais, Thomas (2010). "Ordovician and Silurian sea–water chemistry, sea level, and climate: A synopsis". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 296 (3–4): 389–413. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2010.08.001.

- ^ Samtleben, C.; Munnecke, A.; Bickert, T. (2000). "Development of facies and C/O-isotopes in transects through the Ludlow of Gotland: Evidence for global and local influences on a shallow-marine environment". Facies. 43: 1–38. doi:10.1007/BF02536983.

- ^ Rittner, Don (2009). Encyclopedia of Biology. Infobase Publishing. p. 338. ISBN 9781438109992.

- ^ Lang, W.H.; Cookson, I.C. (1935). "On a flora, including vascular land plants, associated with Monograptus, in rocks of Silurian age, from Victoria, Australia". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B. 224 (517): 421–449. Bibcode:1935RSPTB.224..421L. doi:10.1098/rstb.1935.0004.

- ^ Hueber, F.M. (1983). "A new species of Baragwanathia from the Sextant Formation (Emsian) Northern Ontario, Canada". Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society. 86 (1–2): 57–79. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8339.1983.tb00717.x.

- ^ Bora, Lily (2010). Principles of Paleobotany. Mittal Publications. pp. 36–37.

- ^ a b Niklas, Karl J. (1976). "Chemical Examinations of Some Non-Vascular Paleozoic Plants". Brittonia. 28 (1): 113. doi:10.2307/2805564. JSTOR 2805564.

- ^ Edwards, D. & Wellman, C. (2001), "Embryophytes on Land: The Ordovician to Lochkovian (Lower Devonian) Record", in Gensel, P. & Edwards, D. (eds.), Plants Invade the Land : Evolutionary and Environmental Perspectives, New York: Columbia University Press, pp. 3–28, ISBN 978-0-231-11161-4, p. 4

- ^ Vinn, O.; wilson, M.A.; Mõtus, M.-A. (2014). "Symbiotic endobiont biofacies in the Silurian of Baltica". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 404: 24–29. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2014.03.041. Retrieved 2014-06-11.

- ^ Vinn, O.; Mõtus, M.-A. (2008). "The earliest endosymbiotic mineralized tubeworms from the Silurian of Podolia, Ukraine". Journal of Paleontology. 82 (2): 409–414. doi:10.1666/07-056.1. Retrieved 2014-06-11.

- ^ Garwood, Russell J.; Edgecombe, Gregory D. (September 2011). "Early Terrestrial Animals, Evolution, and Uncertainty". Evolution: Education and Outreach. 4 (3): 489–501. doi:10.1007/s12052-011-0357-y.

- ^ Jeram, Andrew J.; Selden, Paul A.; Edwards, Dianne (1990). "Land Animals in the Silurian: Arachnids and Myriapods from Shropshire, England". Science. 250 (4981): 658–61. Bibcode:1990Sci...250..658J. doi:10.1126/science.250.4981.658. PMID 17810866.

- ^ DiMichele, William A; Hook, Robert W (1992). "The Silurian". In Behrensmeyer, Anna K. (ed.). Terrestrial Ecosystems Through Time: Evolutionary Paleoecology of Terrestrial Plants and Animals. pp. 207–10. ISBN 978-0-226-04155-1.

References[edit]

- Emiliani, Cesare. (1992). Planet Earth : Cosmology, Geology, & the Evolution of Life & the Environment. Cambridge University Press. (Paperback Edition ISBN 0-521-40949-7)

- Mikulic, DG, DEG Briggs, and J Kluessendorf. 1985. A new exceptionally preserved biota from the Lower Silurian of Wisconsin, USA. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, 311B:75-86.

- Moore, RA, DEG Briggs, SJ Braddy, LI Anderson, DG Mikulic, and J Kluessendorf. 2005. A new synziphosurine (Chelicerata: Xiphosura) from the Late Llandovery (Silurian) Waukesha Lagerstatte, Wisconsin, USA. Journal of Paleontology:79(2), pp. 242–250.

- Ogg, Jim; June, 2004, Overview of Global Boundary Stratotype Sections and Points (GSSP's) https://web.archive.org/web/20060716071827/http://www.stratigraphy.org/gssp.htm Original version accessed April 30, 2006, redirected to archive on May 6, 2015.

External links[edit]

| Wikisource has original works on the topic: Paleozoic#Silurian |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Silurian. |

- Palaeos: Silurian

- UCMP Berkeley: The Silurian

- Paleoportal: Silurian strata in U.S., state by state

- USGS:Silurian and Devonian Rocks (U.S.)

- "International Commission on Stratigraphy (ICS)". Geologic Time Scale 2004. Retrieved September 19, 2005.

- Examples of Silurian Fossils

- GeoWhen Database for the Silurian

- Silurian (Chronostratography scale)