Richard Nixon

Richard Nixon | |

|---|---|

| |

| 37th President of the United States | |

| In office January 20, 1969 – August 9, 1974 | |

| Vice President |

|

| Preceded by | Lyndon B. Johnson |

| Succeeded by | Gerald Ford |

| 36th Vice President of the United States | |

| In office January 20, 1953 – January 20, 1961 | |

| President | Dwight D. Eisenhower |

| Preceded by | Alben W. Barkley |

| Succeeded by | Lyndon B. Johnson |

| United States Senator from California | |

| In office December 1, 1950 – January 1, 1953 | |

| Preceded by | Sheridan Downey |

| Succeeded by | Thomas Kuchel |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from California's 12th district | |

| In office January 3, 1947 – November 30, 1950 | |

| Preceded by | Jerry Voorhis |

| Succeeded by | Patrick J. Hillings |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Richard Milhous Nixon January 9, 1913 Yorba Linda, California, U.S. |

| Died | April 22, 1994 (aged 81) New York City, U.S. |

| Resting place | Richard Nixon Presidential Library and Museum |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouse(s) | |

| Children | Tricia Julie |

| Mother | Hannah Milhous |

| Father | Francis A. Nixon |

| Education | Whittier College (BA) Duke University (JD) |

| Signature | |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | United States of America |

| Branch/service | United States Navy |

| Years of service | 1942–1946 (active) 1946–1966 (inactive) |

| Rank | Commander |

| Battles/wars | World War II • South Pacific Theater[1] |

| Awards | Navy and Marine Corps Commendation Medal (2) |

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

Vice presidency

Post-vice presidency

Judicial appointments

Policies

First term

Second term

Post-presidency

Presidential campaigns

|

||

Richard Milhous Nixon (January 9, 1913 – April 22, 1994) served as the 37th president of the United States from 1969 until 1974. A member of the Republican Party, Nixon previously served as the 36th vice president from 1953 to 1961, having rose to national prominence as a representative and senator from California. After five years in the White House that saw the conclusion to the U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War, détente with the Soviet Union and China, and the establishment of the Environmental Protection Agency, he became the only president to resign from the office.

Nixon was born into a poor family in a small town in Southern California. He graduated from Duke University School of Law in 1937 and returned to California to practice law. He and his wife Pat moved to Washington in 1942 to work for the federal government. He served on active duty in the Navy Reserve during World War II. He was elected to the House of Representatives in 1946. His pursuit of the Hiss Case established his reputation as a leading anti-Communist which elevated him to national prominence. In 1950, he was elected to the Senate. He was the running mate of Dwight D. Eisenhower, the Republican Party's presidential nominee in the 1952 election, serving for eight years in that capacity. He waged an unsuccessful presidential campaign in 1960, narrowly losing to John F. Kennedy. Nixon then lost a race for governor of California to Pat Brown in 1962. In 1968, he ran for the presidency again and was elected, defeating Hubert Humphrey and George Wallace in a close election.

Nixon ended American involvement in the war in Vietnam in 1973, ending the military draft that same year. Nixon's visit to China in 1972 eventually led to diplomatic relations between the two nations, and he initiated détente and the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty with the Soviet Union the same year. His administration generally transferred power from federal control to state control. He imposed wage and price controls for 90 days, enforced desegregation of Southern schools, established the Environmental Protection Agency, and began the War on Cancer. He also presided over the Apollo 11 moon landing, which signaled the end of the moon race. He was re-elected in one of the largest electoral landslides in American history in 1972 when he defeated George McGovern.

In his second term, Nixon ordered an airlift to resupply Israeli losses in the Yom Kippur War, a war which led to the oil crisis at home. By late 1973, the Watergate scandal escalated, costing Nixon much of his political support. On August 9, 1974, he resigned in the face of almost certain impeachment and removal from office—the only time an American president has done so. After his resignation, he was issued a controversial pardon by his successor, Gerald Ford. In 20 years of retirement, Nixon wrote his memoirs and nine other books and undertook many foreign trips, thereby rehabilitating his image into that of an elder statesman and leading expert on foreign affairs. He suffered a debilitating stroke on April 18, 1994, and died four days later at age 81.

Early life

Richard Milhous Nixon was born on January 9, 1913, in Yorba Linda, California, in a house built by his father.[2][3] His parents were Hannah (Milhous) Nixon and Francis A. Nixon. His mother was a Quaker, and his father converted from Methodism to the Quaker faith. Through his mother, Nixon was a descendant of the early English settler Thomas Cornell, who was also an ancestor of Ezra Cornell, the founder of Cornell University, as well as of Jimmy Carter and Bill Gates.[4]

Nixon's upbringing was marked by evangelical Quaker observances of the time such as refraining from alcohol, dancing, and swearing. Nixon had four brothers: Harold (1909–33), Donald (1914–87), Arthur (1918–25), and Edward (1930–2019).[5] Four of the five Nixon boys were named after kings who had ruled in medieval or legendary Britain; Richard, for example, was named after Richard the Lionheart.[6][7]

Nixon's early life was marked by hardship, and he later quoted a saying of Eisenhower to describe his boyhood: "We were poor, but the glory of it was we didn't know it".[8] The Nixon family ranch failed in 1922, and the family moved to Whittier, California. In an area with many Quakers, Frank Nixon opened a grocery store and gas station.[9] Richard's younger brother Arthur died in 1925 at the age of seven after a short illness.[10] Richard was twelve years old when a spot was found on his lung. With a family history of tuberculosis, he was forbidden to play sports. Eventually, the spot was found to be scar tissue from an early bout of pneumonia.[11][12]

Primary and secondary education

Richard attended East Whittier Elementary School, where he was president of his eighth-grade class.[13] His parents believed that attending Whittier High School had caused Richard's older brother Harold to live a dissolute lifestyle before he fell ill of tuberculosis (he died of it in 1933), so they sent Richard to the larger Fullerton Union High School.[14][15] He had to ride a school bus for an hour each way during his freshman year, and received excellent grades. Later, he lived with an aunt in Fullerton during the week.[16] He played junior varsity football, and seldom missed a practice, though he was rarely used in games.[17] He had greater success as a debater, winning a number of championships and taking his only formal tutelage in public speaking from Fullerton's Head of English, H. Lynn Sheller. Nixon later remembered Sheller's words, "Remember, speaking is conversation...don't shout at people. Talk to them. Converse with them."[18] Nixon said he tried to use a conversational tone as much as possible.[18]

At the start of his junior year in September 1928, Richard's parents permitted him to transfer to Whittier High School. At Whittier, Nixon suffered his first election defeat when he lost his bid for student body president. He often rose at 4 a.m., to drive the family truck into Los Angeles and purchase vegetables at the market. He then drove to the store to wash and display them before going to school. Harold had been diagnosed with tuberculosis the previous year; when their mother took him to Arizona in the hopes of improving his health, the demands on Richard increased, causing him to give up football. Nevertheless, Richard graduated from Whittier High third in his class of 207.[19]

College and law school education

Nixon was offered a tuition grant to attend Harvard University, but Harold's continued illness and the need for their mother to care for him meant Richard was needed at the store. He remained in his hometown and attended Whittier College with his expenses covered by a bequest from his maternal grandfather.[20] Nixon played for the basketball team; he also tried out for football but lacked the size to play. He remained on the team as a substitute and was noted for his enthusiasm.[21] Instead of fraternities and sororities, Whittier had literary societies. Nixon was snubbed by the only one for men, the Franklins; many of the Franklins were from prominent families, but Nixon was not. He responded by helping to found a new society, the Orthogonian Society.[22] In addition to the society, schoolwork, and work at the store, Nixon found time for a large number of extracurricular activities, becoming a champion debater and gaining a reputation as a hard worker.[23] In 1933, he became engaged to Ola Florence Welch, daughter of the Whittier police chief. They broke up in 1935.[24]

After graduating summa cum laude with a Bachelor of Arts in history from Whittier in 1934, Nixon received a full scholarship to attend Duke University School of Law.[25] The school was new and sought to attract top students by offering scholarships.[26] It paid high salaries to its professors, many of whom had national or international reputations.[27] The number of scholarships was greatly reduced for second- and third-year students, forcing recipients into intense competition.[26] Nixon not only kept his scholarship but was elected president of the Duke Bar Association,[28] inducted into the Order of the Coif,[29] and graduated third in his class in June 1937.[25]

Early career and marriage

After graduating from Duke, Nixon initially hoped to join the FBI. He received no response to his letter of application and learned years later that he had been hired, but his appointment had been canceled at the last minute due to budget cuts.[30] Instead, he returned to California and was admitted to the California bar in 1937. He began practicing in Whittier with the law firm Wingert and Bewley,[25] working on commercial litigation for local petroleum companies and other corporate matters, as well as on wills.[31] In later years, Nixon proudly said he was the only modern president to have previously worked as a practicing attorney. Nixon was reluctant to work on divorce cases, disliking frank sexual talk from women.[32] In 1938, he opened up his own branch of Wingert and Bewley in La Habra, California,[33] and became a full partner in the firm the following year.[34]

In January 1938 Nixon was cast in the Whittier Community Players production of The Dark Tower. There he played opposite a high school teacher named Thelma "Pat" Ryan.[25] Nixon described it in his memoirs as "a case of love at first sight"[35]—for Nixon only, as Pat Ryan turned down the young lawyer several times before agreeing to date him.[36] Once they began their courtship, Ryan was reluctant to marry Nixon; they dated for two years before she assented to his proposal. They wed in a small ceremony on June 21, 1940. After a honeymoon in Mexico, the Nixons began their married life in Whittier.[37] They had two daughters, Tricia (born 1946) and Julie (born 1948).[38]

Military service

In January 1942 the couple moved to Washington, D.C., where Nixon took a job at the Office of Price Administration.[25] In his political campaigns, Nixon would suggest that this was his response to Pearl Harbor, but he had sought the position throughout the latter part of 1941. Both Nixon and his wife believed he was limiting his prospects by remaining in Whittier.[39] He was assigned to the tire rationing division, where he was tasked with replying to correspondence. He did not enjoy the role, and four months later applied to join the United States Navy.[40] As a birthright Quaker, he could have by law claimed exemption from the draft; he might also have been deferred because he worked in government service. In spite of that, Nixon sought a commission in the Navy. His application was successful, and he was appointed a lieutenant junior grade in the U.S Naval Reserve (U.S. Navy Reserve) on June 15, 1942.[41][42]

In October 1942, he was assigned as aide to the commander of the Naval Air Station Ottumwa in Iowa until May 1943.[41] Seeking more excitement, he requested sea duty and on July 2, 1943, was assigned to Marine Aircraft Group 25 and the South Pacific Combat Air Transport Command (SCAT), supporting the logistics of operations in the South Pacific Theater.[43][44][45] On October 1, 1943, Nixon was promoted to lieutenant.[41] Nixon commanded the SCAT forward detachments at Vella Lavella, Bougainville, and finally at Green Island (Nissan Island).[41][45] His unit prepared manifests and flight plans for R4D/C-47 operations and supervised the loading and unloading of the transport aircraft. For this service, he received a Navy Letter of Commendation (awarded a Navy Commendation Ribbon which was later updated to the Navy and Marine Corps Commendation Medal) from his commanding officer for "meritorious and efficient performance of duty as Officer in Charge of the South Pacific Combat Air Transport Command". Upon his return to the U.S., Nixon was appointed the administrative officer of the Alameda Naval Air Station in California. In January 1945 he was transferred to the Bureau of Aeronautics office in Philadelphia to help negotiate the termination of war contracts, and received his second letter of commendation, from the Secretary of the Navy[46] for "meritorious service, tireless effort, and devotion to duty". Later, Nixon was transferred to other offices to work on contracts and finally to Baltimore.[47] On October 3, 1945, he was promoted to lieutenant commander.[41][46] On March 10, 1946, he was relieved of active duty.[41] He resigned his commission on New Year's Day 1946.[48] On June 1, 1953, he was promoted to commander.[41] He retired in the U.S. Naval Reserve on June 6, 1966.[41]

| Navy and Marine Corps Commendation Medal |

American Campaign Medal | ||

| Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal with two stars |

World War II Victory Medal | Armed Forces Reserve Medal with silver hourglass device | |

Rising politician

Congressional career

California congressman (1947−1950)

Republicans in California's 12th congressional district were frustrated by their inability to defeat Democratic representative Jerry Voorhis, They sought a consensus candidate who would run a strong campaign against him. In 1945, they formed a "Committee of 100" to decide on a candidate, hoping to avoid internal dissensions which had led to previous Voorhis victories. After the committee failed to attract higher-profile candidates, Herman Perry, manager of Whittier's Bank of America branch, suggested Nixon, a family friend with whom he had served on the Whittier College Board of Trustees before the war. Perry wrote to Nixon in Baltimore. After a night of excited talk between Nixon and his wife, he responded to Perry with enthusiasm. Nixon flew to California and was selected by the committee. When he left the Navy at the start of 1946, Nixon and his wife returned to Whittier, where Nixon began a year of intensive campaigning.[49][50] He contended that Voorhis had been ineffective as a representative and suggested that Voorhis's endorsement by a group linked to Communists meant that Voorhis must have radical views.[51] Nixon won the election, receiving 65,586 votes to Voorhis's 49,994.[52]

In Congress, Nixon supported the Taft–Hartley Act of 1947, a federal law that monitors the activities and power of labor unions, and he served on the Education and Labor Committee. He was part of the Herter Committee, which went to Europe to report on the need for U.S. foreign aid. Nixon was the youngest member of the committee and the only Westerner.[53] Advocacy by Herter Committee members, including Nixon, led to congressional passage of the Marshall Plan.[54]

In his memoirs, Nixon wrote that he joined the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) "at the end of 1947". However, he was already a HUAC member in early February 1947, when he heard "Enemy Number One" Gerhard Eisler and his sister Ruth Fischer testify. On February 18, 1947, Nixon referred to Eisler's belligerence toward HUAC in his maiden speech to the House. Also by early February 1947, fellow U.S. Representative Charles J. Kersten had introduced him to Father John Francis Cronin in Baltimore. Cronin shared with Nixon his 1945 privately circulated paper "The Problem of American Communism in 1945",[55] with much information from the FBI's William C. Sullivan (who by 1961 would head domestic intelligence under J. Edgar Hoover).[56]

By May 1948, Nixon had co-sponsored a "Mundt–Nixon Bill" to implement "a new approach to the complicated problem of internal communist subversion ... It provided for registration of all Communist Party members and required a statement of the source of all printed and broadcast material issued by organizations that were found to be Communist fronts." He served as floor manager for the Republican Party. On May 19, 1948, the bill passed the House by 319 to 58, but later it failed to pass the Senate.[57] (The Nixon Library cites this bill's passage as Nixon's first significant victory in Congress.)[58]

Nixon first gained national attention in August 1948, when his persistence as a HUAC member helped break the Alger Hiss spy case. While many doubted Whittaker Chambers's allegations that Hiss, a former State Department official, had been a Soviet spy, Nixon believed them to be true and pressed for the committee to continue its investigation. Under suit for defamation filed by Hiss, Chambers produced documents corroborating his allegations. These included paper and microfilm copies that Chambers turned over to House investigators after having hidden them overnight in a field; they became known as the "Pumpkin Papers".[59] Hiss was convicted of perjury in 1950 for denying under oath he had passed documents to Chambers.[60] In 1948, Nixon successfully cross-filed as a candidate in his district, winning both major party primaries,[61] and was comfortably reelected.[62]

U.S. Senate (1950−1953)

In 1949, Nixon began to consider running for the United States Senate against the Democratic incumbent, Sheridan Downey,[63] and entered the race in November.[64] Downey, faced with a bitter primary battle with Representative Helen Gahagan Douglas, announced his retirement in March 1950.[65] Nixon and Douglas won the primary elections[66] and engaged in a contentious campaign in which the ongoing Korean War was a major issue.[67] Nixon tried to focus attention on Douglas's liberal voting record. As part of that effort, a "Pink Sheet" was distributed by the Nixon campaign suggesting that, as Douglas's voting record was similar to that of New York Congressman Vito Marcantonio (believed by some to be a communist), their political views must be nearly identical.[68] Nixon won the election by almost twenty percentage points.[69] During this campaign, Nixon was first called "Tricky Dick" by his opponents for his campaign tactics.[70]

In the Senate, Nixon took a prominent position in opposing global communism, traveling frequently and speaking out against it.[71] He maintained friendly relations with his fellow anti-communist, controversial Wisconsin senator Joseph McCarthy, but was careful to keep some distance between himself and McCarthy's allegations.[72] Nixon also criticized President Harry S. Truman's handling of the Korean War.[71] He supported statehood for Alaska and Hawaii, voted in favor of civil rights for minorities, and supported federal disaster relief for India and Yugoslavia.[73] He voted against price controls and other monetary restrictions, benefits for illegal immigrants, and public power.[73]

Vice presidency (1953–1961)

General Dwight D. Eisenhower was nominated for president by the Republicans in 1952. He had no strong preference for a vice presidential candidate, and Republican officeholders and party officials met in a "smoke-filled room" and recommended Nixon to the general, who agreed to the senator's selection. Nixon's youth (he was then 39), stance against communism, and political base in California—one of the largest states—were all seen as vote-winners by the leaders. Among the candidates considered along with Nixon were Ohio Senator Robert A. Taft, New Jersey Governor Alfred Driscoll and Illinois Senator Everett Dirksen.[74][75] On the campaign trail, Eisenhower spoke to his plans for the country, leaving the negative campaigning to his running mate.[76]

In mid-September, the Republican ticket faced a major crisis.[77] The media reported that Nixon had a political fund, maintained by his backers, which reimbursed him for political expenses.[78] Such a fund was not illegal but it exposed Nixon to allegations of possible conflict of interest. With pressure building for Eisenhower to demand Nixon's resignation from the ticket the senator went on television to deliver an address to the nation on September 23, 1952.[79] The address, later termed the Checkers speech, was heard by about 60 million Americans—including the largest television audience up to that point.[80] Nixon emotionally defended himself, stating that the fund was not secret, nor had donors received special favors. He painted himself as a man of modest means (his wife had no mink coat; instead she wore a "respectable Republican cloth coat") and a patriot.[79] The speech would be remembered for the gift which Nixon had received, but which he would not give back: "a little cocker spaniel dog ... sent all the way from Texas. And our little girl—Tricia, the 6-year-old—named it Checkers."[79] The speech prompted a huge public outpouring of support for Nixon.[81] Eisenhower decided to retain him on the ticket,[82] which proved victorious in the November election.[76]

Eisenhower gave Nixon responsibilities during his term as vice president—more than any previous vice president.[83] Nixon attended Cabinet and National Security Council meetings and chaired them when Eisenhower was absent. A 1953 tour of the Far East succeeded in increasing local goodwill toward the United States and prompted Nixon to appreciate the potential of the region as an industrial center. He visited Saigon and Hanoi in French Indochina.[84] On his return to the United States at the end of 1953, Nixon increased the amount of time he devoted to foreign relations.[85]

Biographer Irwin Gellman, who chronicled Nixon's congressional years, said of his vice presidency:

Eisenhower radically altered the role of his running mate by presenting him with critical assignments in both foreign and domestic affairs once he assumed his office. The vice president welcomed the president's initiatives and worked energetically to accomplish White House objectives. Because of the collaboration between these two leaders, Nixon deserves the title, "the first modern vice president".[86]

Despite intense campaigning by Nixon, who reprised his strong attacks on the Democrats, the Republicans lost control of both houses of Congress in the 1954 elections. These losses caused Nixon to contemplate leaving politics once he had served out his term.[87] On September 24, 1955, President Eisenhower suffered a heart attack; his condition was initially believed to be life-threatening. Eisenhower was unable to perform his duties for six weeks. The 25th Amendment to the United States Constitution had not yet been proposed, and the Vice President had no formal power to act. Nonetheless, Nixon acted in Eisenhower's stead during this period, presiding over Cabinet meetings and ensuring that aides and Cabinet officers did not seek power.[88] According to Nixon biographer Stephen Ambrose, Nixon had "earned the high praise he received for his conduct during the crisis ... he made no attempt to seize power".[89]

His spirits buoyed, Nixon sought a second term, but some of Eisenhower's aides aimed to displace him. In a December 1955 meeting, Eisenhower proposed that Nixon not run for reelection in order to give him administrative experience before a 1960 presidential run and instead become a Cabinet officer in a second Eisenhower administration. Nixon believed such an action would destroy his political career. When Eisenhower announced his reelection bid in February 1956, he hedged on the choice of his running mate, saying it was improper to address that question until he had been renominated. Although no Republican was opposing Eisenhower, Nixon received a substantial number of write-in votes against the President in the 1956 New Hampshire primary election. In late April, the President announced that Nixon would again be his running mate.[90] Eisenhower and Nixon were reelected by a comfortable margin in the November 1956 election.[91]

In early 1957, Nixon undertook another major foreign trip, this time to Africa. On his return, he helped shepherd the Civil Rights Act of 1957 through Congress. The bill was weakened in the Senate, and civil rights leaders were divided over whether Eisenhower should sign it. Nixon advised the President to sign the bill, which he did.[92] Eisenhower suffered a mild stroke in November 1957, and Nixon gave a press conference, assuring the nation that the Cabinet was functioning well as a team during Eisenhower's brief illness.[93]

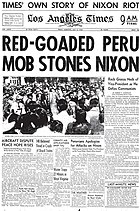

On April 27, 1958, Richard and Pat Nixon reluctantly embarked on a goodwill tour of South America. In Montevideo, Uruguay, Nixon made an impromptu visit to a college campus, where he fielded questions from students on U.S. foreign policy. The trip was uneventful until the Nixon party reached Lima, Peru, where he was met with student demonstrations. Nixon went to the historical campus of National University of San Marcos, the oldest university in the Americas, got out of his car to confront the students, and stayed until forced back into the car by a volley of thrown objects. At his hotel, Nixon faced another mob, and one demonstrator spat on him.[94] In Caracas, Venezuela, Nixon and his wife were spat on by anti-American demonstrators and their limousine was attacked by a pipe-wielding mob.[95] According to Ambrose, Nixon's courageous conduct "caused even some of his bitterest enemies to give him some grudging respect".[96] Reporting to the cabinet after the trip, Nixon claimed there was "absolute proof that [the protestors] were directed and controlled by a central Communist conspiracy." Secretary of State John Foster Dulles concurred in this view; Director of Central Intelligence Allen Dulles sharply rebuked it.[97]

In July 1959 President Eisenhower sent Nixon to the Soviet Union for the opening of the American National Exhibition in Moscow. On July 24, Nixon was touring the exhibits with Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev when the two stopped at a model of an American kitchen and engaged in an impromptu exchange about the merits of capitalism versus communism that became known as the "Kitchen Debate".[98]

1960 and 1962 elections; wilderness years

In 1960 Nixon launched his first campaign for President of the United States. He faced little opposition in the Republican primaries[99] and chose former Massachusetts Senator Henry Cabot Lodge Jr. as his running mate.[100] His Democratic opponent was John F. Kennedy and the race remained close for the duration.[101] Nixon campaigned on his experience but Kennedy called for new blood and claimed the Eisenhower–Nixon administration had allowed the Soviet Union to overtake the U.S. in ballistic missiles (the "missile gap").[102]

A new political medium was introduced in the campaign: televised presidential debates. In the first of four such debates Nixon appeared pale, with a five o'clock shadow, in contrast to the photogenic Kennedy.[100] Nixon's performance in the debate was perceived to be mediocre in the visual medium of television, though many people listening on the radio thought Nixon had won.[103] Nixon narrowly lost the election; Kennedy won the popular vote by only 112,827 votes (0.2 percent).[100]

There were charges of voter fraud in Texas and Illinois, both states won by Kennedy. Nixon refused to consider contesting the election, feeling a lengthy controversy would diminish the United States in the eyes of the world and the uncertainty would hurt U.S. interests.[104] At the end of his term of office as vice president in January 1961, Nixon and his family returned to California, where he practiced law and wrote a bestselling book, Six Crises, which included coverage of the Hiss case, Eisenhower's heart attack, and the Fund Crisis, which had been resolved by the Checkers speech.[100][105]

Local and national Republican leaders encouraged Nixon to challenge incumbent Pat Brown for Governor of California in the 1962 election.[100] Despite initial reluctance, Nixon entered the race.[100] The campaign was clouded by public suspicion that Nixon viewed the office as a stepping stone for another presidential run, some opposition from the far-right of the party, and his own lack of interest in being California's governor.[100] Nixon hoped a successful run would confirm his status as the nation's leading active Republican politician, and ensure he remained a major player in national politics.[106] Instead, he lost to Brown by more than five percentage points, and the defeat was widely believed to be the end of his political career.[100] In an impromptu concession speech the morning after the election, Nixon blamed the media for favoring his opponent, saying, "You won't have Nixon to kick around anymore because, gentlemen, this is my last press conference."[107] The California defeat was highlighted in the November 11, 1962, episode of ABC's Howard K. Smith: News and Comment, titled "The Political Obituary of Richard M. Nixon".[108] Alger Hiss appeared on the program, and many members of the public complained that it was unseemly to give a convicted felon air time to attack a former vice president. The furor drove Smith and his program from the air,[109] and public sympathy for Nixon grew.[108]

In 1963 the Nixon family traveled to Europe, where Nixon gave press conferences and met with leaders of the countries he visited.[110] The family moved to New York City, where Nixon became a senior partner in the leading law firm Nixon, Mudge, Rose, Guthrie & Alexander.[100] When announcing his California campaign, Nixon had pledged not to run for president in 1964; even if he had not, he believed it would be difficult to defeat Kennedy, or after his assassination, Kennedy's successor, Lyndon Johnson.[111]

In 1964, he supported Arizona Senator Barry Goldwater for the Republican nomination for U.S. president; when Goldwater won the nomination, Nixon was selected to introduce him at the convention. Although he thought Goldwater unlikely to win, Nixon campaigned for him loyally. The election was a disaster for the Republicans; Goldwater's landslide loss to Johnson was matched by heavy losses for the party in Congress and among state governors.[112]

Nixon was one of the few leading Republicans not blamed for the disastrous results, and he sought to build on that in the 1966 Congressional elections. He campaigned for many Republicans, seeking to regain seats lost in the Johnson landslide, and received credit for helping the Republicans make major gains that year.[113]

1968 presidential election

At the end of 1967, Nixon told his family he planned to run for president a second time. Although Pat Nixon did not always enjoy public life[114] (for example, she had been embarrassed by the need to reveal how little the family owned in the Checkers speech),[115] she was supportive of her husband's ambitions. Nixon believed that with the Democrats torn over the issue of the Vietnam War, a Republican had a good chance of winning, although he expected the election to be as close as in 1960.[114]

One of the most tumultuous primary election seasons ever began as the Tet Offensive was launched in January 1968. President Johnson withdrew as a candidate in March, after doing unexpectedly poorly in the New Hampshire primary. In June, Senator Robert F. Kennedy, a Democratic candidate, was assassinated just moments after his victory in the California primary. On the Republican side, Nixon's main opposition was Michigan Governor George Romney, though New York Governor Nelson Rockefeller and California Governor Ronald Reagan each hoped to be nominated in a brokered convention. Nixon secured the nomination on the first ballot.[116] He selected Maryland Governor Spiro Agnew as his running mate, a choice which Nixon believed would unite the party, appealing both to Northern moderates and to Southerners disaffected with the Democrats.[117]

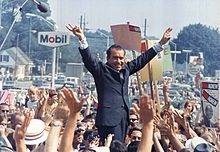

Nixon's Democratic opponent in the general election was Vice President Hubert Humphrey, who was nominated at a convention marked by violent protests.[118] Throughout the campaign, Nixon portrayed himself as a figure of stability during a period of national unrest and upheaval.[118] He appealed to what he later called the "silent majority" of socially conservative Americans who disliked the hippie counterculture and the anti-war demonstrators. Agnew became an increasingly vocal critic of these groups, solidifying Nixon's position with the right.[119]

Nixon waged a prominent television advertising campaign, meeting with supporters in front of cameras.[120] He stressed that the crime rate was too high, and attacked what he perceived as a surrender by the Democrats of the United States' nuclear superiority.[121] Nixon promised "peace with honor" in the Vietnam War and proclaimed that "new leadership will end the war and win the peace in the Pacific".[122] He did not release specifics of how he hoped to end the war, resulting in media intimations that he must have a "secret plan".[122] His slogan of "Nixon's the One" proved to be effective.[120]

Johnson's negotiators hoped to reach a truce, or at least a cessation of bombings, in Vietnam prior to the election. On October 22, 1968, candidate Nixon received information that Johnson was preparing a so-called "October surprise" to elect Humphrey in the last days of the campaign, and his administration had abandoned three non-negotiable conditions for a bombing halt.[123] Whether the Nixon campaign interfered with any ongoing negotiations between the Johnson administration and the South Vietnamese by engaging Anna Chennault, a prominent Chinese-American fundraiser for the Republican party, remains an ongoing controversy. While notes uncovered in 2016 may support such a contention, the context of said notes remains of debate.[123] It is not clear whether the government of South Vietnam needed much encouragement to opt out of a peace process they considered disadvantageous.[124]

In a three-way race between Nixon, Humphrey, and American Independent Party candidate former Alabama Governor George Wallace, Nixon defeated Humphrey by nearly 500,000 votes (seven-tenths of a percentage point), with 301 electoral votes to 191 for Humphrey and 46 for Wallace.[118][125] In his victory speech, Nixon pledged that his administration would try to bring the divided nation together.[126] Nixon said: "I have received a very gracious message from the Vice President, congratulating me for winning the election. I congratulated him for his gallant and courageous fight against great odds. I also told him that I know exactly how he felt. I know how it feels to lose a close one."[127]

Presidency (1969–1974)

Nixon was inaugurated as president on January 20, 1969, sworn in by his onetime political rival, Chief Justice Earl Warren. Pat Nixon held the family Bibles open at Isaiah 2:4, which reads, "They shall beat their swords into plowshares, and their spears into pruning hooks." In his inaugural address, which received almost uniformly positive reviews, Nixon remarked that "the greatest honor history can bestow is the title of peacemaker"[128]—a phrase that would later be placed on his gravestone.[129] He spoke about turning partisan politics into a new age of unity:

In these difficult years, America has suffered from a fever of words; from inflated rhetoric that promises more than it can deliver; from angry rhetoric that fans discontents into hatreds; from bombastic rhetoric that postures instead of persuading. We cannot learn from one another until we stop shouting at one another, until we speak quietly enough so that our words can be heard as well as our voices.[130]

Foreign policy

The relationship between Nixon and Henry Kissinger, his National Security Advisor was unusually close. It has been compared to the relationships of Woodrow Wilson and Colonel House, or Franklin D. Roosevelt and Harry Hopkins.[131] In all three cases, State Department was relegated to a backseat role in developing foreign-policy.[132] Historian David Rothkopf has compared the personalities of Nixon and Kissinger:

- They were a fascinating pair. In a way, they complemented each other perfectly. Kissinger was the charming and worldly Mr. Outside who provided the grace and intellectual-establishment respectability that Nixon lacked, disdained and aspired to. Kissinger was an international citizen. Nixon very much a classic American. Kissinger had a worldview and a facility for adjusting it to meet the times, Nixon had pragmatism and a strategic vision that provided the foundations for their policies. Kissinger would, of course, say he was not political like Nixon—but in fact he was just as political as Nixon, just as calculating, just as relentlessly ambitious ... these self-made men were driven as much by their need for approval and their neuroses as by their strengths.[133]

China

Nixon laid the groundwork for his overture to China before he became president, writing in Foreign Affairs a year before his election: "There is no place on this small planet for a billion of its potentially most able people to live in angry isolation."[134] Assisting him in this venture was Kissinger, in charge of his United States National Security Council and future Secretary of State. They collaborated closely, bypassing Cabinet officials. With relations between the Soviet Union and China at a nadir—border clashes between the two took place during Nixon's first year in office—Nixon sent private word to the Chinese that he desired closer relations. A breakthrough came in early 1971, when Chairman Mao invited a team of American table tennis players to visit China and play against top Chinese players. Nixon followed up by sending Kissinger to China for clandestine meetings with Chinese officials.[134] On July 15, 1971, it was simultaneously announced by Beijing and by Nixon (on television and radio) that the President would visit China the following February. The announcements astounded the world.[135] The secrecy allowed both sets of leaders time to prepare the political climate in their countries for the contact.[136]

In February 1972, Nixon and his wife traveled to China. Kissinger briefed Nixon for over 40 hours in preparation.[137] Upon touching down, the President and First Lady emerged from Air Force One and greeted Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai. Nixon made a point of shaking Zhou's hand, something which then-Secretary of State John Foster Dulles had refused to do in 1954 when the two met in Geneva.[138] More than a hundred television journalists accompanied the president. On Nixon's orders, television was strongly favored over printed publications, as Nixon felt that the medium would capture the visit much better than print. It also gave him the opportunity to snub the print journalists he despised.[138]

Nixon and Kissinger met for an hour with Mao and Zhou at Mao's official private residence, where they discussed a range of issues.[139] Mao later told his doctor that he had been impressed by Nixon, whom he considered forthright, unlike the leftists and the Soviets.[139] He said he was suspicious of Kissinger,[139] though the National Security Advisor referred to their meeting as his "encounter with history".[138] A formal banquet welcoming the presidential party was given that evening in the Great Hall of the People. The following day, Nixon met with Zhou; the joint communique following this meeting recognized Taiwan as a part of China, and looked forward to a peaceful solution to the problem of reunification.[140] When not in meetings, Nixon toured architectural wonders including the Forbidden City, Ming Tombs, and the Great Wall.[138] Americans received their first glimpse into Chinese life through the cameras which accompanied Pat Nixon, who toured the city of Beijing and visited communes, schools, factories, and hospitals.[138]

The visit ushered in a new era of Sino-American relations.[118] Fearing the possibility of a Sino-American alliance, the Soviet Union yielded to pressure for détente with the United States.[141]

Vietnam War

When Nixon took office, about 300 American soldiers were dying each week in Vietnam,[142] and the war was broadly unpopular in the United States, with ongoing violent protests against the war. The Johnson administration had agreed to suspend bombing in exchange for negotiations without preconditions, but this agreement never fully took force. According to Walter Isaacson, soon after taking office, Nixon had concluded that the Vietnam War could not be won and he was determined to end the war quickly.[143] He sought some arrangement which would permit American forces to withdraw, while leaving South Vietnam secure against attack.[144]

Nixon approved a secret B-52 carpet bombing campaign of North Vietnamese (and, later, allied Khmer Rouge) positions in Cambodia in March 1969 (code-named Operation Menu), without the consent of Cambodian leader Norodom Sihanouk.[145][146][147] In mid-1969, Nixon began efforts to negotiate peace with the North Vietnamese, sending a personal letter to North Vietnamese leaders, and peace talks began in Paris. Initial talks, however, did not result in an agreement.[148] In May 1969 he publicly proposed to withdraw all American troops from South Vietnam provided North Vietnam also did so and for South Vietnam to hold internationally supervised elections with Viet Cong participation.[149]

In July 1969, Nixon visited South Vietnam, where he met with his U.S. military commanders and President Nguyễn Văn Thiệu. Amid protests at home demanding an immediate pullout, he implemented a strategy of replacing American troops with Vietnamese troops, known as "Vietnamization".[118] He soon instituted phased U.S. troop withdrawals,[150] but also authorized incursions into Laos, in part to interrupt the Ho Chi Minh trail, which passed through Laos and Cambodia and was used to supply North Vietnamese forces. Nixon announced the ground invasion of Cambodia to the American public on April 30, 1970.[151] Further protests erupted against what was perceived as an expansion of the conflict, and the unrest escalated to violence when Ohio National Guardsmen shot and killed four unarmed students on May 4.[152] Nixon's responses to protesters included an impromptu, early morning meeting with them at the Lincoln Memorial on May 9, 1970.[153][154][155] Documents uncovered from the Soviet archives after 1991 reveal that the North Vietnamese attempt to overrun Cambodia in 1970 was launched at the explicit request of the Khmer Rouge and negotiated by Pol Pot's then-second-in-command, Nuon Chea.[156] Nixon's campaign promise to curb the war, contrasted with the escalated bombing, led to claims that Nixon had a "credibility gap" on the issue.[150] It is estimated that between 50,000 and 150,000 people were killed during the bombing of Cambodia between 1970 and 1973.[146]

In 1971, excerpts from the "Pentagon Papers", which had been leaked by Daniel Ellsberg, were published by The New York Times and The Washington Post. When news of the leak first appeared, Nixon was inclined to do nothing; the Papers, a history of United States' involvement in Vietnam, mostly concerned the lies of prior administrations and contained few real revelations. He was persuaded by Kissinger that the Papers were more harmful than they appeared, and the President tried to prevent publication. The Supreme Court eventually ruled for the newspapers.[157]

As U.S. troop withdrawals continued, conscription was reduced and in 1973 ended; the armed forces became all-volunteer.[158] After years of fighting, the Paris Peace Accords were signed at the beginning of 1973. The agreement implemented a cease fire and allowed for the withdrawal of remaining American troops without requiring the 160,000 North Vietnam Army regulars located in the South to withdraw.[159] Once American combat support ended, there was a brief truce, before fighting broke out again. North Vietnam conquered South Vietnam in 1975.[160]

Latin American policy

Nixon had been a firm supporter of Kennedy during the 1961 Bay of Pigs Invasion and 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis. On taking office in 1969, he stepped up covert operations against Cuba and its president, Fidel Castro. He maintained close relations with the Cuban-American exile community through his friend, Bebe Rebozo, who often suggested ways of irritating Castro. These activities concerned the Soviets and Cubans, who feared Nixon might attack Cuba and break the understanding between Kennedy and Khrushchev which had ended the missile crisis. In August 1970, the Soviets asked Nixon to reaffirm the understanding; despite his hard line against Castro, Nixon agreed. The process had not yet been completed when the Soviets began expanding their base at the Cuban port of Cienfuegos in October 1970. A minor confrontation ensued, which was concluded with an understanding that the Soviets would not use Cienfuegos for submarines bearing ballistic missiles. The final round of diplomatic notes, reaffirming the 1962 accord, were exchanged in November.[161]

The election of Marxist candidate Salvador Allende as President of Chile in September 1970 spurred Nixon and Kissinger to pursue a vigorous campaign of covert resistance to Allende,[162]:25 first designed to convince the Chilean congress to confirm Jorge Alessandri as the winner of the election and then messages to military officers in support of a coup.[162] Other support included strikes organized against Allende and funding for Allende opponents. It was even alleged that "Nixon personally authorized" $700,000 in covert funds to print anti-Allende messages in a prominent Chilean newspaper.[162]:93 Following an extended period of social, political, and economic unrest, General Augusto Pinochet assumed power in a violent coup d'état on September 11, 1973; among the dead was Allende.[163]

Soviet Union

Nixon used the improving international environment to address the topic of nuclear peace. Following the announcement of his visit to China, the Nixon administration concluded negotiations for him to visit the Soviet Union. The President and First Lady arrived in Moscow on May 22, 1972, and met with Leonid Brezhnev, the General Secretary of the Communist Party; Alexei Kosygin, the Chairman of the Council of Ministers; and Nikolai Podgorny, the head of state, among other leading Soviet officials.[164]

Nixon engaged in intense negotiations with Brezhnev.[164] Out of the summit came agreements for increased trade and two landmark arms control treaties: SALT I, the first comprehensive limitation pact signed by the two superpowers,[118] and the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty, which banned the development of systems designed to intercept incoming missiles. Nixon and Brezhnev proclaimed a new era of "peaceful coexistence". A banquet was held that evening at the Kremlin.[164]

Nixon and Kissinger planned to link arms control to détente and to the resolution of other urgent problems through what Nixon called "linkage." David Tal argues:

- The linkage between strategic arms limitations and outstanding issues such as the Middle East, Berlin and, foremost, Vietnam thus became central to Nixon's and Kissinger's policy of détente. Through employment of linkage, they hoped to change the nature and course of U.S. foreign policy, including U.S. nuclear disarmament and arms control policy, and to separate them from those practiced by Nixon's predecessors. They also intended, through linkage, to make U.S. arms control policy part of détente ... His policy of linkage had in fact failed. It failed mainly because it was based on flawed assumptions and false premises, the foremost of which was that the Soviet Union wanted strategic arms limitation agreement much more than the United States did.[165]

Seeking to foster better relations with the United States, China and the Soviet Union both cut back on their diplomatic support for North Vietnam and advised Hanoi to come to terms militarily.[166] Nixon later described his strategy:

I had long believed that an indispensable element of any successful peace initiative in Vietnam was to enlist, if possible, the help of the Soviets and the Chinese. Though rapprochement with China and détente with the Soviet Union were ends in themselves, I also considered them possible means to hasten the end of the war. At worst, Hanoi was bound to feel less confident if Washington was dealing with Moscow and Beijing. At best, if the two major Communist powers decided that they had bigger fish to fry, Hanoi would be pressured into negotiating a settlement we could accept.[167]

During the previous two years, Nixon had made considerable progress in U.S.–Soviet relations, and he embarked on a second trip to the Soviet Union in 1974.[168] He arrived in Moscow on June 27 to a welcome ceremony, cheering crowds, and a state dinner at the Grand Kremlin Palace that evening.[168] Nixon and Brezhnev met in Yalta, where they discussed a proposed mutual defense pact, détente, and MIRVs. Nixon considered proposing a comprehensive test-ban treaty, but he felt he would not have time to complete it during his presidency.[168] There were no significant breakthroughs in these negotiations.[168]

Middle Eastern policy

As part of the Nixon Doctrine, the U.S. avoided giving direct combat assistance to its allies and instead gave them assistance to defend themselves. During the Nixon administration, the U.S. greatly increased arms sales to the Middle East, particularly Israel, Iran and Saudi Arabia.[169] The Nixon administration strongly supported Israel, an American ally in the Middle East, but the support was not unconditional. Nixon believed Israel should make peace with its Arab neighbors and that the U.S. should encourage it. The president believed that—except during the Suez Crisis—the U.S. had failed to intervene with Israel, and should use the leverage of the large U.S. military aid to Israel to urge the parties to the negotiating table. The Arab-Israeli conflict was not a major focus of Nixon's attention during his first term—for one thing, he felt that no matter what he did, American Jews would oppose his reelection.[a]

On October 6, 1973, an Arab coalition led by Egypt and Syria, supported with arms and materiel by the Soviet Union, attacked Israel in the Yom Kippur War. Israel suffered heavy losses and Nixon ordered an airlift to resupply Israeli losses, cutting through inter-departmental squabbles and bureaucracy and taking personal responsibility for any response by Arab nations. More than a week later, by the time the U.S. and Soviet Union began negotiating a truce, Israel had penetrated deep into enemy territory. The truce negotiations rapidly escalated into a superpower crisis; when Israel gained the upper hand, Egyptian President Sadat requested a joint U.S.–USSR peacekeeping mission, which the U.S. refused. When Soviet Premier Brezhnev threatened to unilaterally enforce any peacekeeping mission militarily, Nixon ordered the U.S. military to DEFCON3,[170] placing all U.S. military personnel and bases on alert for nuclear war. This was the closest the world had come to nuclear war since the Cuban Missile Crisis. Brezhnev backed down as a result of Nixon's actions.[171]

Because Israel's victory was largely due to U.S. support, the Arab OPEC nations retaliated by refusing to sell crude oil to the U.S., resulting in the 1973 oil crisis.[172] The embargo caused gasoline shortages and rationing in the United States in late 1973, and was eventually ended by the oil-producing nations as peace in the Middle East took hold.[173]

After the war, and under Nixon's presidency, the U.S. reestablished relations with Egypt for the first time since 1967. Nixon used the Middle East crisis to restart the stalled Middle East Peace Negotiations; he wrote in a confidential memo to Kissinger on October 20:

I believe that, beyond a doubt, we are now facing the best opportunity we have had in 15 years to build a lasting peace in the Middle East. I am convinced history will hold us responsible if we let this opportunity slip by ... I now consider a permanent Middle East settlement to be the most important final goal to which we must devote ourselves.[174]

Nixon made one of his final international visits as president to the Middle East in June 1974, and became the first President to visit Israel.[175]

Domestic policy

Economy

At the time Nixon took office in 1969, inflation was at 4.7 percent—its highest rate since the Korean War. The Great Society had been enacted under Johnson, which, together with the Vietnam War costs, was causing large budget deficits. Unemployment was low, but interest rates were at their highest in a century.[176] Nixon's major economic goal was to reduce inflation; the most obvious means of doing so was to end the war.[176] This could not be accomplished overnight, and the U.S. economy continued to struggle through 1970, contributing to a lackluster Republican performance in the midterm congressional elections (Democrats controlled both Houses of Congress throughout Nixon's presidency).[177] According to political economist Nigel Bowles in his 2011 study of Nixon's economic record, the new president did little to alter Johnson's policies through the first year of his presidency.[178]

Nixon was far more interested in foreign affairs than domestic policies, but he believed that voters tend to focus on their own financial condition, and that economic conditions were a threat to his reelection. As part of his "New Federalism" views, he proposed grants to the states, but these proposals were for the most part lost in the congressional budget process. However, Nixon gained political credit for advocating them.[177] In 1970, Congress had granted the President the power to impose wage and price freezes, though the Democratic majorities, knowing Nixon had opposed such controls through his career, did not expect Nixon to actually use the authority.[178] With inflation unresolved by August 1971, and an election year looming, Nixon convened a summit of his economic advisers at Camp David. He then announced temporary wage and price controls, allowed the dollar to float against other currencies, and ended the convertibility of the dollar into gold.[179] Bowles points out,

by identifying himself with a policy whose purpose was inflation's defeat, Nixon made it difficult for Democratic opponents ... to criticize him. His opponents could offer no alternative policy that was either plausible or believable since the one they favored was one they had designed but which the president had appropriated for himself.[178]

Nixon's policies dampened inflation through 1972, although their aftereffects contributed to inflation during his second term and into the Ford administration.[179]

After Nixon won re-election, inflation was returning.[180] He reimposed price controls in June 1973. The price controls became unpopular with the public and businesspeople, who saw powerful labor unions as preferable to the price board bureaucracy.[180] The controls produced food shortages, as meat disappeared from grocery stores and farmers drowned chickens rather than sell them at a loss.[180] Despite the failure to control inflation, controls were slowly ended, and on April 30, 1974, their statutory authorization lapsed.[180]

Governmental initiatives and organization

Nixon advocated a "New Federalism", which would devolve power to state and local elected officials, though Congress was hostile to these ideas and enacted few of them.[181] He eliminated the Cabinet-level United States Post Office Department, which in 1971 became the government-run United States Postal Service.[182]

Nixon was a late supporter of the conservation movement. Environmental policy had not been a significant issue in the 1968 election, and the candidates were rarely asked for their views on the subject. Nixon broke new ground by discussing environmental policy in his State of the Union speech in 1970. He saw that the first Earth Day in April 1970 presaged a wave of voter interest on the subject, and sought to use that to his benefit; in June he announced the formation of the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA).[183] He relied on his domestic advisor John Ehrlichman, who favored protection of natural resources, to keep him "out of trouble on environmental issues."[184] Other initiatives supported by Nixon included the Clean Air Act of 1970 and the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), and the National Environmental Policy Act required environmental impact statements for many Federal projects.[184][183] Nixon vetoed the Clean Water Act of 1972—objecting not to the policy goals of the legislation but to the amount of money to be spent on them, which he deemed excessive. After Congress overrode his veto, Nixon impounded the funds he deemed unjustifiable.[185]

In 1971, Nixon proposed health insurance reform—a private health insurance employer mandate,[b] federalization of Medicaid for poor families with dependent minor children,[186] and support for health maintenance organizations (HMOs).[187] A limited HMO bill was enacted in 1973.[187] In 1974, Nixon proposed more comprehensive health insurance reform—a private health insurance employer mandate[b] and replacement of Medicaid by state-run health insurance plans available to all, with income-based premiums and cost sharing.[188]

Nixon was concerned about the prevalence of domestic drug use in addition to drug use among American soldiers in Vietnam. He called for a War on Drugs and pledged to cut off sources of supply abroad. He also increased funds for education and for rehabilitation facilities.[189]

As one policy initiative, Nixon called for more money for sickle-cell research, treatment, and education in February 1971[190] and signed the National Sickle Cell Anemia Control Act on May 16, 1972.[191][192][c] While Nixon called for increased spending on such high-profile items as sickle-cell disease and for a War on Cancer, at the same time he sought to reduce overall spending at the National Institutes of Health.[193]

Civil rights

The Nixon presidency witnessed the first large-scale integration of public schools in the South.[194] Nixon sought a middle way between the segregationist Wallace and liberal Democrats, whose support of integration was alienating some Southern whites.[195] Hopeful of doing well in the South in 1972, he sought to dispose of desegregation as a political issue before then. Soon after his inauguration, he appointed Vice President Agnew to lead a task force, which worked with local leaders—both white and black—to determine how to integrate local schools. Agnew had little interest in the work, and most of it was done by Labor Secretary George Shultz. Federal aid was available, and a meeting with President Nixon was a possible reward for compliant committees. By September 1970, less than ten percent of black children were attending segregated schools. By 1971, however, tensions over desegregation surfaced in Northern cities, with angry protests over the busing of children to schools outside their neighborhood to achieve racial balance. Nixon opposed busing personally but enforced court orders requiring its use.[196]

Some scholars, such as James Morton Turner and John Isenberg, believe that Nixon, who had advocated for civil rights in his 1960 campaign, slowed down desegregation as president, appealing to the racial conservatism of Southern whites, who were angered by the civil rights movement. This, he hoped, would boost his election chances in 1972.[197][198]

In addition to desegregating public schools, Nixon implemented the Philadelphia Plan in 1970—the first significant federal affirmative action program.[199] He also endorsed the Equal Rights Amendment after it passed both houses of Congress in 1972 and went to the states for ratification.[200] He also pushed for African American civil rights and economic equity through a concept known as black capitalism.[201] Nixon had campaigned as an ERA supporter in 1968, though feminists criticized him for doing little to help the ERA or their cause after his election. Nevertheless, he appointed more women to administration positions than Lyndon Johnson had.[202]

Space policy

After a nearly decade-long national effort, the United States won the race to land astronauts on the Moon on July 20, 1969, with the flight of Apollo 11. Nixon spoke with Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin during their moonwalk. He called the conversation "the most historic phone call ever made from the White House".[203]

Nixon was unwilling to keep funding for the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) at the high level seen during the 1960s as NASA prepared to send men to the Moon. NASA Administrator Thomas O. Paine drew up ambitious plans for the establishment of a permanent base on the Moon by the end of the 1970s and the launch of a manned expedition to Mars as early as 1981. Nixon rejected both proposals due to the expense.[204] Nixon also canceled the Air Force Manned Orbital Laboratory program in 1969, because unmanned spy satellites were a more cost-effective way to achieve the same reconnaissance objective.[205] NASA cancelled the last three planned Apollo lunar missions to place Skylab in orbit more efficiently and free money up for the design and construction of the Space Shuttle.[206]

On May 24, 1972, Nixon approved a five-year cooperative program between NASA and the Soviet space program, culminating in the 1975 joint mission of an American Apollo and Soviet Soyuz spacecraft linking in space.[207]

Reelection, Watergate scandal, and resignation

1972 presidential campaign

Nixon believed his rise to power had peaked at a moment of political realignment. The Democratic "Solid South" had long been a source of frustration to Republican ambitions. Goldwater had won several Southern states by opposing the Civil Rights Act of 1964 but had alienated more moderate Southerners. Nixon's efforts to gain Southern support in 1968 were diluted by Wallace's candidacy. Through his first term, he pursued a Southern Strategy with policies, such as his desegregation plans, that would be broadly acceptable among Southern whites, encouraging them to realign with the Republicans in the aftermath of the civil rights movement. He nominated two Southern conservatives, Clement Haynsworth and G. Harrold Carswell to the Supreme Court, but neither was confirmed by the Senate.[208]

Nixon entered his name on the New Hampshire primary ballot on January 5, 1972, effectively announcing his candidacy for reelection.[209] Virtually assured the Republican nomination,[210] the President had initially expected his Democratic opponent to be Massachusetts Senator Edward M. Kennedy (brother of the late President), who was largely removed from contention after the July 1969 Chappaquiddick incident.[211] Instead, Maine Senator Edmund Muskie became the front runner, with South Dakota Senator George McGovern in a close second place.[209]

On June 10, McGovern won the California primary and secured the Democratic nomination.[212] The following month, Nixon was renominated at the 1972 Republican National Convention. He dismissed the Democratic platform as cowardly and divisive.[213] McGovern intended to sharply reduce defense spending[214] and supported amnesty for draft evaders as well as abortion rights. With some of his supporters believed to be in favor of drug legalization, McGovern was perceived as standing for "amnesty, abortion and acid". McGovern was also damaged by his vacillating support for his original running mate, Missouri Senator Thomas Eagleton, dumped from the ticket following revelations that he had received treatment for depression.[215][216] Nixon was ahead in most polls for the entire election cycle, and was reelected on November 7, 1972, in one of the largest landslide election victories in American history. He defeated McGovern with over 60 percent of the popular vote, losing only in Massachusetts and D.C.[217]

Watergate

The term Watergate has come to encompass an array of clandestine and often illegal activities undertaken by members of the Nixon administration. Those activities included "dirty tricks," such as bugging the offices of political opponents, and the harassment of activist groups and political figures. The activities were brought to light after five men were caught breaking into the Democratic party headquarters at the Watergate complex in Washington, D.C. on June 17, 1972. The Washington Post picked up on the story; reporters Carl Bernstein and Bob Woodward relied on an informant known as "Deep Throat"—later revealed to be Mark Felt, associate director at the FBI—to link the men to the Nixon administration. Nixon downplayed the scandal as mere politics, calling news articles biased and misleading. A series of revelations made it clear that the Committee to Re-elect President Nixon, and later the White House, was involved in attempts to sabotage the Democrats. Senior aides such as White House Counsel John Dean faced prosecution; in total 48 officials were convicted of wrongdoing.[118][218][219]

In July 1973, White House aide Alexander Butterfield testified under oath to Congress that Nixon had a secret taping system and recorded his conversations and phone calls in the Oval Office. These tapes were subpoenaed by Watergate Special Counsel Archibald Cox; Nixon provided transcripts of the conversations but not the actual tapes, citing executive privilege. With the White House and Cox at loggerheads, Nixon had Cox fired in October in the "Saturday Night Massacre"; he was replaced by Leon Jaworski. In November, Nixon's lawyers revealed that a tape of conversations held in the White House on June 20, 1972, had an 18 1⁄2 minute gap.[219] Rose Mary Woods, the President's personal secretary, claimed responsibility for the gap, saying that she had accidentally wiped the section while transcribing the tape, but her story was widely mocked. The gap, while not conclusive proof of wrongdoing by the President, cast doubt on Nixon's statement that he had been unaware of the cover-up.[220]

Though Nixon lost much popular support, even from his own party, he rejected accusations of wrongdoing and vowed to stay in office.[219] He admitted he had made mistakes but insisted he had no prior knowledge of the burglary, did not break any laws, and did not learn of the cover-up until early 1973.[221] On October 10, 1973, Vice President Agnew resigned for reasons unrelated to Watergate: he was convicted on charges of bribery, tax evasion and money laundering during his tenure as governor of Maryland. Believing his first choice, John Connally, would not be confirmed by Congress,[222] Nixon chose Gerald Ford, Minority Leader of the House of Representatives, to replace Agnew.[223] One researcher suggests Nixon effectively disengaged from his own administration after Ford was sworn in as vice president on December 6, 1973.[224]

On November 17, 1973, during a televised question-and-answer session,[225] with 400 Associated Press managing editors Nixon said, "People have got to know whether or not their President is a crook. Well, I'm not a crook. I've earned everything I've got."[226]

The legal battle over the tapes continued through early 1974, and in April Nixon announced the release of 1,200 pages of transcripts of White House conversations between himself and his aides. The House Judiciary Committee opened impeachment hearings against the President on May 9, 1974, which were televised on the major TV networks. These hearings culminated in votes for impeachment.[221] On July 24, the Supreme Court ruled unanimously that the full tapes, not just selected transcripts, must be released.[227]

The scandal grew to involve a slew of additional allegations against the President, ranging from the improper use of government agencies to accepting gifts in office and his personal finances and taxes; Nixon repeatedly stated his willingness to pay any outstanding taxes due, and later paid $465,000 (equivalent to $2.4 million in 2019) in back taxes in 1974.[228]

Even with support diminished by the continuing series of revelations, Nixon hoped to fight the charges. But one of the new tapes, recorded soon after the break-in, demonstrated that Nixon had been told of the White House connection to the Watergate burglaries soon after they took place, and had approved plans to thwart the investigation. In a statement accompanying the release of what became known as the "Smoking Gun Tape" on August 5, 1974, Nixon accepted blame for misleading the country about when he had been told of White House involvement, stating that he had had a lapse of memory.[229] Senate Minority Leader Hugh Scott, Senator Barry Goldwater, and House Minority Leader John Jacob Rhodes met with Nixon soon after. Rhodes told Nixon he faced certain impeachment in the House. Scott and Goldwater told the president that he had, at most, only 15 votes in his favor in the Senate, far fewer than the 34 needed to avoid removal from office.[230]

Resignation

In light of his loss of political support and the near-certainty that he would be impeached and removed from office, Nixon resigned the presidency on August 9, 1974, after addressing the nation on television the previous evening.[221] The resignation speech was delivered from the Oval Office and was carried live on radio and television. Nixon said he was resigning for the good of the country and asked the nation to support the new president, Gerald Ford. Nixon went on to review the accomplishments of his presidency, especially in foreign policy.[231] He defended his record as president, quoting from Theodore Roosevelt's 1910 speech Citizenship in a Republic:

Sometimes I have succeeded and sometimes I have failed, but always I have taken heart from what Theodore Roosevelt once said about the man in the arena, "whose face is marred by dust and sweat and blood, who strives valiantly, who errs and comes up short again and again because there is not effort without error and shortcoming, but who does actually strive to do the deed, who knows the great enthusiasms, the great devotions, who spends himself in a worthy cause, who at the best knows in the end the triumphs of high achievements and who at the worst, if he fails, at least fails while daring greatly".[232]

Nixon's speech received generally favorable initial responses from network commentators, with only Roger Mudd of CBS stating that Nixon had not admitted wrongdoing.[233] It was termed "a masterpiece" by Conrad Black, one of his biographers. Black opined that "What was intended to be an unprecedented humiliation for any American president, Nixon converted into a virtual parliamentary acknowledgement of almost blameless insufficiency of legislative support to continue. He left while devoting half his address to a recitation of his accomplishments in office."[234]

Post-presidency (1974–1994)

Pardon and illness

Following his resignation, the Nixons flew to their home La Casa Pacifica in San Clemente, California.[235] According to his biographer, Jonathan Aitken, "Nixon was a soul in torment" after his resignation.[236] Congress had funded Nixon's transition costs, including some salary expenses, though reducing the appropriation from $850,000 to $200,000. With some of his staff still with him, Nixon was at his desk by 7:00 a.m.—with little to do.[236] His former press secretary, Ron Ziegler, sat with him alone for hours each day.[237]

Nixon's resignation had not put an end to the desire among many to see him punished. The Ford White House considered a pardon of Nixon, even though it would be unpopular in the country. Nixon, contacted by Ford emissaries, was initially reluctant to accept the pardon, but then agreed to do so. Ford insisted on a statement of contrition, but Nixon felt he had not committed any crimes and should not have to issue such a document. Ford eventually agreed, and on September 8, 1974, he granted Nixon a "full, free, and absolute pardon", which ended any possibility of an indictment. Nixon then released a statement:

I was wrong in not acting more decisively and more forthrightly in dealing with Watergate, particularly when it reached the stage of judicial proceedings and grew from a political scandal into a national tragedy. No words can describe the depth of my regret and pain at the anguish my mistakes over Watergate have caused the nation and the presidency, a nation I so deeply love, and an institution I so greatly respect.[238][239]

In October 1974, Nixon fell ill with phlebitis. Told by his doctors that he could either be operated on or die, a reluctant Nixon chose surgery, and President Ford visited him in the hospital. Nixon was under subpoena for the trial of three of his former aides—Dean, Haldeman, and John Ehrlichman—and The Washington Post, disbelieving his illness, printed a cartoon showing Nixon with a cast on the "wrong foot". Judge John Sirica excused Nixon's presence despite the defendants' objections.[240] Congress instructed Ford to retain Nixon's presidential papers—beginning a three-decade legal battle over the documents that was eventually won by the former president and his estate.[241] Nixon was in the hospital when the 1974 midterm elections were held, and Watergate and the pardon were contributing factors to the Republican loss of 43 seats in the House and three in the Senate.[242]

Return to public life

In December 1974, Nixon began planning his comeback despite the considerable ill will against him in the country. He wrote in his diary, referring to himself and Pat,

So be it. We will see it through. We've had tough times before and we can take the tougher ones that we will have to go through now. That is perhaps what we were made for—to be able to take punishment beyond what anyone in this office has had before particularly after leaving office. This is a test of character and we must not fail the test.[243]

By early 1975, Nixon's health was improving. He maintained an office in a Coast Guard station 300 yards from his home, at first taking a golf cart and later walking the route each day; he mainly worked on his memoirs.[244] He had hoped to wait before writing his memoirs; the fact that his assets were being eaten away by expenses and lawyer fees compelled him to begin work quickly.[245] He was handicapped in this work by the end of his transition allowance in February, which compelled him to part with many of his staff, including Ziegler.[246] In August of that year, he met with British talk-show host and producer David Frost, who paid him $600,000 (equivalent to $2.9 million in 2019) for a series of sit-down interviews, filmed and aired in 1977.[247] They began on the topic of foreign policy, recounting the leaders he had known, but the most remembered section of the interviews was that on Watergate. Nixon admitted he had "let down the country" and that "I brought myself down. I gave them a sword and they stuck it in. And they twisted it with relish. And, I guess, if I'd been in their position, I'd have done the same thing."[248] The interviews garnered 45–50 million viewers—becoming the most-watched program of its kind in television history.[249]

The interviews helped improve Nixon's financial position—at one point in early 1975 he had only $500 in the bank—as did the sale of his Key Biscayne property to a trust set up by wealthy Nixon friends such as Bebe Rebozo.[250] In February 1976, Nixon visited China at the personal invitation of Mao. Nixon had wanted to return to China, but chose to wait until after Ford's own visit in 1975.[251] Nixon remained neutral in the close 1976 primary battle between Ford and Reagan. Ford won, but was defeated by Georgia Governor Jimmy Carter in the general election. The Carter administration had little use for Nixon and blocked his planned trip to Australia, causing the government of Prime Minister Malcolm Fraser to withhold its official invitation.[252]

In 1976, Nixon was disbarred by the New York State Bar Association for obstruction of justice in the Watergate affair. Nixon chose not to present any defense.[253] In early 1978, Nixon went to the United Kingdom. He was shunned by American diplomats and by most ministers of the James Callaghan government. He was welcomed, however, by the Leader of the Opposition, Margaret Thatcher, as well as by former prime ministers Lord Home and Sir Harold Wilson. Two other former prime ministers, Harold Macmillan and Edward Heath, declined to meet him. Nixon addressed the Oxford Union regarding Watergate:

Some people say I didn't handle it properly and they're right. I screwed it up. Mea culpa. But let's get on to my achievements. You'll be here in the year 2000 and we'll see how I'm regarded then.[254]

Author and elder statesman

In 1978, Nixon published his memoirs, RN: The Memoirs of Richard Nixon, the first of ten books he was to author in his retirement.[235] The book was a bestseller and attracted a generally positive critical response.[255] Nixon visited the White House in 1979, invited by Carter for the state dinner for Chinese Vice Premier Deng Xiaoping. Carter had not wanted to invite Nixon, but Deng had said he would visit Nixon in California if the former president was not invited. Nixon had a private meeting with Deng and visited Beijing again in mid-1979.[256]