Anu

| Anu | |

|---|---|

Sky Father, King of the Gods, Lord of the Constellations | |

| |

| Abode | north pole, Draco |

| Army | Stars and deities |

| Symbol | 𒀭 Dingir |

| Personal information | |

| Parents | Apsu and Nammu (Sumerian religion) Anshar and Kishar (East Semitic) Alalu (Hittite religion) |

| Consort | Uraš (early Sumerian), Ki (later Sumerian), Antu (East Semitic), Nammu (Neo-Sumerian) |

| Children | Enlil, Enki, Nikikurga, Nidaba, Baba, in some versions: Inanna, Kumarbi (Hurrians), Anammelech (Possibly) |

| Greek equivalent | Ouranos, Zeus[1][2] |

| Roman equivalent | Caelus, Jupiter[1][2] |

| Canaanite equivalent | El |

Anu[a] or An[b] is the divine personification of the sky, supreme god, and ancestor of all the deities in ancient Mesopotamian religion. Anu was believed to be the supreme source of all authority, for the other gods and for all mortal rulers, and he is described in one text as the one "who contains the entire universe". He is identified with the north ecliptic pole centered in the constellation Draco and, along with his sons Enlil and Enki, constitutes the highest divine triad personifying the three bands of constellations of the vault of the sky. By the time of the earliest written records, Anu was rarely worshipped, and veneration was instead devoted to his son Enlil, but, throughout Mesopotamian history, the highest deity in the pantheon was always said to possess the anûtu, meaning "Heavenly power". Anu's primary role in myths is as the ancestor of the Anunnaki, the major deities of Sumerian religion. His primary cult center was the Eanna temple in the city of Uruk, but, by the Akkadian Period (c. 2334 – 2154 BC), his authority in Uruk had largely been ceded to the goddess Inanna, the Queen of Heaven.

Anu's consort in the earliest Sumerian texts is the goddess Uraš, but she is later the goddess Ki and, in Akkadian texts, the goddess Antu, whose name is a feminine form of Anu. Anu briefly appears in the Akkadian Epic of Gilgamesh, in which his daughter Ishtar (the East Semitic equivalent to Inanna) persuades him to give her the Bull of Heaven so that she may send it to attack Gilgamesh. The incident results in the death of Enkidu. In another legend, Anu summons the mortal hero Adapa before him for breaking the wing of the south wind. Anu orders for Adapa to be given the food and water of immortality, which Adapa refuses, having been warned beforehand by Enki that Anu will offer him the food and water of death. In ancient Hittite religion, Anu is a former ruler of the gods, who was overthrown by his son Kumarbi, who bit off his father's genitals and gave birth to the storm god Teshub. Teshub overthrew Kumarbi, avenged Anu's mutilation, and became the new king of the gods. This story was the later basis for the castration of Ouranos in Hesiod's Theogony.

Worship[edit]

In Mesopotamian religion, Anu was the personification of the sky, the utmost power,[7] the supreme god,[8] the one "who contains the entire universe".[9] He was identified with the north ecliptic pole centered in Draco.[10] His name meant the "One on High",[7] and together with his sons Enlil and Enki (Ellil[11] and Ea[12] in Akkadian), he formed a triune conception of the divine, in which Anu represented a "transcendental" obscurity,[7] Enlil the "transcendent" and Enki the "immanent" aspect of the divine.[13]. The three great gods and the three divisions of the heavens were Anu (the ancient god of the heavens), Enlil (son of Anu, god of the air and the forces of nature, and lord of the gods), and Ea (the beneficent god of earth and life, who dwelt in the abyssal waters). The Babylonians divided the sky into three parts named after them: The equator and most of the zodiac occupied the Way of Anu, the northern sky was the Way of Enlil, and the southern sky was the Way of Ea[14]. The boundaries of each Way were at 17°N and 17°S. [15]

Though Anu was the supreme god,[4][16] he was rarely worshipped, and, by the time that written records began, the most important cult was devoted to his son Enlil.[17][18] Anu's primary role in the Sumerian pantheon was as an ancestor figure; the most powerful and important deities in the Sumerian pantheon were believed to be the offspring of Anu and his consort Ki.[16][19][20] These deities were known as the Anunnaki,[21] which means "offspring of Anu".[21] Although it is sometimes unclear which deities were considered members of the Anunnaki,[22] the group probably included the "seven gods who decree":[22] Anu, Enlil, Enki, Ninhursag, Nanna, Utu, and Inanna.[23]

Anu's main cult center was the Eanna temple, whose name means "House of Heaven" (Sumerian: e2-anna; Cuneiform: 𒂍𒀭 E2.AN),[c] in Uruk.[d] Although the temple was originally dedicated to Anu,[6] it was later transformed into the primary cult center of Inanna.[6] After its dedication to Inanna, the temple seems to have housed priestesses of the goddess.[6]

Anu was believed to be source of all legitimate power; he was the one who bestowed the right to rule upon gods and kings alike.[16][25][4] According to scholar Stephen Bertman, Anu "...was the supreme source of authority among the gods, and among men, upon whom he conferred kingship. As heaven's grand patriarch, he dispensed justice and controlled the laws known as the meh that governed the universe."[25] In inscriptions commemorating his conquest of Sumer, Sargon of Akkad, the founder of the Akkadian Empire, proclaims Anu and Inanna as the sources of his authority.[25] A hymn from the early second millennium BC professes that "his utterance ruleth over the obedient company of the gods".[25]

Anu's original name in Sumerian is An, of which Anu is a Semiticized form.[26][27] Anu was also identified with the Semitic god Ilu or El from early on.[26] The functions of Anu and Enlil frequently overlapped, especially during later periods as the cult of Anu continued to wane and the cult of Enlil rose to greater prominence.[17][18] In later times, Anu was fully superseded by Enlil.[4] Eventually, Enlil was, in turn, superseded by Marduk, the national god of ancient Babylon.[4] Nonetheless, references to Anu's power were preserved through archaic phrases used in reference to the ruler of the gods.[4] The highest god in the pantheon was always said to possess the anûtu, which literally means "Heavenly power".[4] In the Babylonian Enûma Eliš, the gods praise Marduk, shouting "Your word is Anu!"[4]

Although Anu was a very important deity, his nature was often ambiguous and ill-defined;[16] he almost never appears in Mesopotamian artwork[16] and has no known anthropomorphic iconography.[16] During the Kassite Period (c. 1600 BC — c. 1155 BC) and Neo-Assyrian Period (911 BC — 609 BC), Anu was represented by a horned cap.[16][25] The Amorite god Amurru was sometimes equated with Anu.[4] Later, during the Seleucid Empire (213 BC — 63 BC), Anu was identified with Enmešara and Dumuzid.[4]

Family[edit]

The earliest Sumerian texts make no mention of where Anu came from or how he came to be the ruler of the gods;[4] instead, his preeminence is simply assumed.[4] In early Sumerian texts from the third millennium BC, Anu's consort is the goddess Uraš;[16][4] the Sumerians later attributed this role to Ki, the personification of the earth.[16][4] The Sumerians believed that rain was Anu's seed[28] and that, when it fell, it impregnated Ki, causing her to give birth to all the vegetation of the land.[28] During the Akkadian Period, Ki was supplanted by Antu, a goddess whose name is probably a feminine form of Anu.[16][4] The Akkadians believed that rain was milk from the clouds,[28] which they believed were Antu's breasts.[28]

Anu is commonly described as the "father of the gods",[4] and a vast array of deities were thought to have been his offspring over the course of Mesopotamian history.[4] Inscriptions from Lagash dated to the late third millennium BC identify Anu as the father of Gatumdug, Baba, and Ninurta.[4] Later literary texts proclaim Adad, Enki, Enlil, Girra, Nanna-Suen, Nergal and Šara as his sons and Inanna-Ishtar, Nanaya, Nidaba, Ninisinna, Ninkarrak, Ninmug, Ninnibru, Ninsumun, Nungal, and Nusku as his daughters.[4] The demons Lamaštu, Asag, and the Sebettu were thought to have been Anu's creations.[4] In Hittite mythology, Anu is the son of the god Alalu.[29][30]

Mythology[edit]

Sumerian[edit]

Sumerian creation myth[edit]

The main source of information about the Sumerian creation myth is the prologue to the epic poem Gilgamesh, Enkidu, and the Netherworld (ETCSL 1.8.1.4),[31] which briefly describes the process of creation: at first, there is only Nammu, the primeval sea.[32] Then, Nammu gives birth to An (the Sumerian name for Anu), the sky, and Ki, the earth.[33] An and Ki mate with each other, causing Ki to give birth to Enlil, the god of the wind.[33] Enlil separates An from Ki and carries off the earth as his domain, while An carries off the sky.[34]

In Sumerian, the designation "An" was used interchangeably with "the heavens" so that in some cases it is doubtful whether, under the term, the god An or the heavens is being denoted.[35][36] In Sumerian cosmogony, heaven was envisioned as a series of three domes covering the flat earth;[37][4] Each of these domes of heaven was believed to be made of a different precious stone.[37] An was believed to be the highest and outermost of these domes, which was thought to be made of reddish stone.[4] Outside of this dome was the primordial body of water known as Nammu.[33] An's sukkal, or attendant, was the god Ilabrat.[4]

Inanna myths[edit]

Inanna and Ebih (ETCSL 1.3.2), otherwise known as Goddess of the Fearsome Divine Powers, is a 184-line poem written in Sumerian by the Akkadian poetess Enheduanna.[38] It describes An's granddaughter Inanna's confrontation with Mount Ebih, a mountain in the Zagros mountain range.[38] An briefly appears in a scene from the poem in which Inanna petitions him to allow her to destroy Mount Ebih.[38] An warns Inanna not to attack the mountain,[38] but she ignores his warning and proceeds to attack and destroy Mount Ebih regardless.[38]

The poem Inanna Takes Command of Heaven is an extremely fragmentary, but important, account of Inanna's conquest of the Eanna temple in Uruk.[6] It begins with a conversation between Inanna and her brother Utu in which Inanna laments that the Eanna temple is not within their domain and resolves to claim it as her own.[6] The text becomes increasingly fragmentary at this point in the narrative,[6] but appears to describe her difficult passage through a marshland to reach the temple, while a fisherman instructs her on which route is best to take.[6] Ultimately, Inanna reaches An, who is shocked by her arrogance, but nevertheless concedes that she has succeeded and that the temple is now her domain.[6] The text ends with a hymn expounding Inanna's greatness.[6] This myth may represent an eclipse in the authority of the priests of An in Uruk and a transfer of power to the priests of Inanna.[6]

Akkadian[edit]

Epic of Gilgamesh[edit]

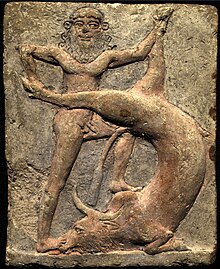

In a scene from the Akkadian Epic of Gilgamesh, written in the late second millennium BC, Anu's daughter Ishtar, the East Semitic equivalent to Inanna, attempts to seduce the hero Gilgamesh.[40] When Gilgamesh spurns her advances,[40] Ishtar angrily goes to heaven and tells Anu that Gilgamesh has insulted her.[40] Anu asks her why she is complaining to him instead of confronting Gilgamesh herself.[40] Ishtar demands that Anu give her the Bull of Heaven[40] and swears that if he does not give it to her, she will break down the gates of the Underworld and raise the dead to eat the living.[40] Anu gives Ishtar the Bull of Heaven, and Ishtar sends it to attack Gilgamesh and his friend Enkidu.[41]

Adapa myth[edit]

In the myth of Adapa, which is first attested during the Kassite Period, Anu notices that the south wind does not blow towards the land for seven days.[42] He asks his sukkal Ilabrat the reason.[42] Ilabrat replies that is because Adapa, the priest of Ea (the East Semitic equivalent of Enki) in Eridu, has broken the south wind's wing.[42] Anu demands that Adapa be summoned before him,[42] but, before Adapa sets out, Ea warns him not to eat any of the food or drink any of the water the gods offer him, because the food and water are poisoned.[43] Adapa arrives before Anu and tells him that the reason he broke the south wind's wing was because he had been fishing for Ea and the south wind had caused a storm, which had sunk his boat.[44] Anu's doorkeepers Dumuzid and Ningishzida speak out in favor of Adapa.[44] This placates Anu's fury and he orders that, instead of the food and water of death, Adapa should be given the food and water of immortality as a reward.[44] Adapa, however, follows Ea's advice and refuses the meal.[44] The story of Adapa was beloved by scribes, who saw him as the founder of their trade[45] and a vast plethora of copies and variations of the myth have been found across Mesopotamia, spanning the entire course of Mesopotamian history.[46] The story of Adapa's appearance before Anu has been compared to the later Jewish story of Adam and Eve, recorded in the Book of Genesis.[47] In the same way that Anu forces Adapa to return to earth after he refuses to eat the food of immortality, Yahweh in the biblical story drives Adam out of the Garden of Eden to prevent him from eating the fruit from the tree of life.[48] Similarly, Adapa was seen as the prototype for all priests;[48] whereas Adam in the Book of Genesis is presented as the prototype of all mankind.[48]

Erra and Išum[edit]

In the epic poem Erra and Išum, which was written in Akkadian in the eighth century BC, Anu gives Erra, the god of destruction, the Sebettu, which are described as personified weapons.[4] Anu instructs Erra to use them to massacre humans when they become overpopulated and start making too much noise (Tablet I, 38ff).[4]

Hittite[edit]

In Hittite mythology, Anu overthrows his father Alalu[29][30] and proclaims himself ruler of the universe.[29][30] He himself is later overthrown by his own son Kumarbi;[29][30] Anu attempts to flee, but Kumarbi bites off Anu's genitals and swallows them.[29][49] Kumarbi then banishes Anu to the underworld,[29] along with his allies, the old gods,[50][51] whom the Hittites syncretized with the Anunnaki.[50] As a consequence of swallowing Anu's genitals, Kumarbi becomes impregnated with Anu's son Teshub and four other offspring.[29][49] After he grows to maturity, Teshub overthrows his father Kumarbi, thus avenging his other father Anu's overthrow and mutilation.[29]

Later influence[edit]

The series of divine coups described in the Hittite creation myth later became the basis for the Greek creation story described in the long poem Theogony, written by the Boeotian poet Hesiod in the seventh century BC.[52][49] In Hesiod's poem, the primeval sky-god Ouranos is overthrown and castrated by his son Kronos in much the same manner that Anu is overthrown and castrated by Kumarbi in the Hittite story.[52][53][49] Kronos is then, in turn, overthrown by his own son Zeus.[52][49] In one Orphic myth, Kronos bites off Ouranos's genitals in exactly the same manner that Kumarbi does to Anu in the Hittite myth.[49] Nonetheless, Robert Mondi notes that Ouranos never held mythological significance to the Greeks comparable with Anu's significance to the Mesopotamians.[54] Instead, Mondi calls Ouranos "a pale reflection of Anu",[55] noting that "apart from the castration myth, he has very little significance as a cosmic personality at all and is not associated with kingship in any systematic way."[55]

According to Walter Burkert, an expert on ancient Greek religion, direct parallels also exist between Anu and the Greek god Zeus.[2] In particular, the scene from Tablet VI of the Epic of Gilgamesh in which Ishtar comes before Anu after being rejected by Gilgamesh and complains to her mother Antu, but is mildly rebuked by Anu, is directly paralleled by a scene from Book V of the Iliad.[56] In this scene, Aphrodite, the later Greek development of Ishtar, is wounded by the Greek hero Diomedes while trying to save her son Aeneas.[57] She flees to Mount Olympus, where she cries to her mother Dione, is mocked by her sister Athena, and is mildly rebuked by her father Zeus.[57] Not only is the narrative parallel significant,[57] but so is the fact that Dione's name is a feminization of Zeus's own, just as Antu is a feminine form of Anu.[57] Dione does not appear throughout the rest of the Iliad, in which Zeus's consort is instead the goddess Hera.[57] Burkert therefore concludes that Dione is clearly a calque of Antu.[57]

The most direct equivalent to Anu in the Canaanite pantheon is Shamem, the personification of the sky,[55] but Shamem almost never appears in myths[55] and it is unclear whether the Canaanites ever regarded him as a previous ruler of the gods at all.[55] Instead, the Canaanites seem to have ascribed Anu's attributes to El, the current ruler of the gods.[55] In later times, the Canaanites equated El with Kronos rather than with Ouranos, and El's son Baal with Zeus.[55] A narrative from Canaanite mythology describes the warrior-goddess Anat coming before El after being insulted, in a way that directly parallels Ishtar coming before Anu in the Epic of Gilgamesh.[55]

El is characterized as the malk olam ("the eternal king") and, like Anu, he is "consistently depicted as old, just, compassionate, and patriarchal".[55] In the same way that Anu was thought to wield the Tablet of Destinies, Canaanite texts mentions decrees issued by El that he alone may alter.[55] In late antiquity, writers such as Philo of Byblos attempted to impose the dynastic succession framework of the Hittite and Hesiodic stories onto Canaanite mythology,[58] but these efforts are forced and contradict what most Canaanites seem to have actually believed.[58] Most Canaanites seem to have regarded El and Baal as ruling concurrently:[59]

"El is king, Baal becomes king. Both are kings over other gods, but El's kingship is timeless and unchanging. Baal must acquire his kingship, affirm it through the building of his temple, and defend it against adversaries; even so he loses it, and must be enthroned anew. El's kingship is static, Baal's is dynamic."[55]

See also[edit]

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Anu |

| Look up anu in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

Notes[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ a b Jordan 1993, p. 22.

- ^ a b c Burkert 2005, pp. 295, 299–300.

- ^ Clay 2006, p. 101.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y Stephens 2013.

- ^ Piveteau 1981, pp. 16–17.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Harris 1991, pp. 261–278.

- ^ a b c James 1963, p. 140.

- ^ James 1963, p. 23 ff.

- ^ Parpola 1993, p. 180, note 77.

- ^ Vv.Aa. 1951, pp. 300–301.

- ^ Stone 2016.

- ^ Horry 2016.

- ^ Saggs 1987, p. 191.

- ^ Rogers 1998, p. 12.

- ^ Rogers 1998, p. 16.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Black & Green 1992, p. 30.

- ^ a b Schneider 2011, p. 58.

- ^ a b Kramer 1963, p. 118.

- ^ Katz 2003, p. 403.

- ^ Leick 1998, p. 8.

- ^ a b Black & Green 1992, p. 34.

- ^ a b Kramer 1963, p. 123.

- ^ Kramer 1963, pp. 122–123.

- ^ Halloran 2006.

- ^ a b c d e Mark 2017.

- ^ a b Pope 1955, p. 2.

- ^ Clay 2006, pp. 100–101.

- ^ a b c d Nemet-Nejat 1998, p. 182.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Puhvel 1987, p. 25.

- ^ a b c d Coleman & Davidson 2015, p. 19.

- ^ Kramer 1961, pp. 30–33.

- ^ Kramer 1961, pp. 37-40.

- ^ a b c Kramer 1961, pp. 37–40.

- ^ Kramer 1961, pp. 37–41.

- ^ Levine 2000, p. 4.

- ^ Leeming & Page 1996, p. 109.

- ^ a b Nemet-Nejat 1998, p. 180.

- ^ a b c d e Karahashi 2004, p. 111.

- ^ Dalley 1989, pp. 80–82.

- ^ a b c d e f Dalley 1989, p. 80.

- ^ Dalley 1989, pp. 81–82.

- ^ a b c d McCall 1990, p. 65.

- ^ McCall 1990, pp. 65–66.

- ^ a b c d McCall 1990, p. 66.

- ^ Sanders 2017, pp. 38–39.

- ^ Sanders 2017, pp. 38–65.

- ^ Liverani 2004, pp. 21–23.

- ^ a b c Liverani 2004, p. 22.

- ^ a b c d e f Burkert 2005, p. 295.

- ^ a b Leick 1998, p. 141.

- ^ Van Scott 1998, p. 187.

- ^ a b c Puhvel 1987, pp. 25–27.

- ^ Mondi 1990, pp. 168–170.

- ^ Mondi 1990, pp. 169–170.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Mondi 1990, p. 170.

- ^ Burkert 2005, pp. 299–300.

- ^ a b c d e f Burkert 2005, p. 300.

- ^ a b Mondi 1990, pp. 170–171.

- ^ Mondi 1990, p. 171.

Bibliography[edit]

- Vv.Aa. (1951), University of California Publications in Semitic Philology, 11–12, University of California Press, OCLC 977787419CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bertman,Stephen. Handbook to Life in Ancient Mesopotamia,Facts On File,2003, ISBN 0-8160-4346-9.

- Black, Jeremy; Green, Anthony (1992), Gods, Demons and Symbols of Ancient Mesopotamia: An Illustrated Dictionary, The British Museum Press, ISBN 0-7141-1705-6CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Burkert, Walter (2005), "Chapter Twenty: Near Eastern Connections", in Foley, John Miles (ed.), A Companion to Ancient Epic, New York City, New York and London, England: Blackwell Publishing, ISBN 978-1-4051-0524-8CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Coleman, J. A.; Davidson, George (2015), The Dictionary of Mythology: An A-Z of Themes, Legends, and Heroes, London, England: Arcturus Publishing Limited, ISBN 978-1-78404-478-7CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Clay, Albert Tobias (2006) [1923], The Origin of Biblical Traditions: Hebrew Legends in Babylonia and Israel, Eugene, Oregon: Wipf & Stock Publishers, ISBN 978-1-59752-718-7CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dalley, Stephanie (1989), Myths from Mesopotamia: Creation, the Flood, Gilgamesh, and Others, Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-283589-0CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Halloran, John A. (2006), Sumerian Lexicon: Version 3.0CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Harris, Rivkah (February 1991), "Inanna-Ishtar as Paradox and a Coincidence of Opposites", History of Religions, 30 (3): 261–278, doi:10.1086/463228, JSTOR 1062957CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Horry, Ruth (2016), "Enki/Ea (god)", Ancient Mesopotamian Gods and Goddesses, Open Richly Annotated Cuneiform Corpus, UK Higher Education AcademyCS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- James, Edwin Oliver (1963), The Worship of the Sky-god: A Comparative Study in Semitic and Indo-European Religion, Athlone Press, ASIN B000PD61S2, OCLC 236664CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jordan, Michael (1993), Encyclopedia of Gods: Over 2,500 Deities of the World, New York: Facts on File, Inc., ISBN 978-0-8160-2909-9CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Karahashi, Fumi (April 2004), "Fighting the Mountain: Some Observations on the Sumerian Myths of Inanna and Ninurta", Journal of Near Eastern Studies, 63 (2): 111–118, doi:10.1086/422302, JSTOR 422302CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Katz, D. (2003), The Image of the Underworld in Sumerian Sources, Bethesda, Maryland: CDL Press, ISBN 978-1-883053-77-2CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kramer, Samuel Noah (1961), Sumerian Mythology: A Study of Spiritual and Literary Achievement in the Third Millennium B.C.: Revised Edition, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: University of Pennsylvania Press, ISBN 0-8122-1047-6CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kramer, Samuel Noah (1963), The Sumerians: Their History, Culture, and Character, Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press, ISBN 0-226-45238-7CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Leeming, David Adams; Page, Jack (1996), God: Myths of the Male Divine, Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-511387-7CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Leick, Gwendolyn (1998) [1991], A Dictionary of Ancient Near Eastern Mythology, New York City, New York: Routledge, ISBN 0-415-19811-9CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Levine, Etan (2000), "Air in Biblical Thought", Heaven and Earth, Law and Love: Studies in Biblical Thought, Herausgegeben von Otto Kaiser, Berlin, Germany and New York City, New York: Walter de Gruyter, ISBN 3-11-016952-5CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Liverani, Mario (2004), Myth and Politics in Ancient Near Eastern Historiography, Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press, ISBN 978-0-8014-7358-6CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mark, Joshua (20 January 2017), "Anu", Ancient History Encyclopedia, Ancient History EncyclopediaCS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- McCall, Henrietta (1990), Mesopotamian Myths, The Legendary Past, Austin, Texas: University of Texas Press, ISBN 0-292-75130-3CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mondi, Robert (1990), "Greek and Near Eastern Mythology: Greek Mythic Thought in the Light of the Near East", in Edmunds, Lowell (ed.), Approaches to Greek Myth, Baltimore, Maryland: The Johns Hopkins University Press, ISBN 0-8018-3864-9CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Nemet-Nejat, Karen Rhea (1998), Daily Life in Ancient Mesopotamia, Daily Life, Greenwood, ISBN 978-0-313-29497-6CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Parpola, Simo (1993), "The Assyrian Tree of Life: Tracing the Origins of Jewish Monotheism and Greek Philosophy" (PDF), Journal of Near Eastern Studies, 52 (3): 161–208, doi:10.1086/373622, JSTOR 545436CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Piveteau, Jean (1981) [1964], "Man Before History", in Dunan, Marcel; Bowle, John (eds.), The Larousse Encyclopedia of Ancient and Medieval History, New York City, New York: Excaliber Books, ISBN 0-89673-083-2CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pope, Marvin H. (1955), El in the Ugaritic Texts, 2, Leiden, The Netherlands: E. J. Brill, ISSN 0083-5889CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Puhvel, Jaan (1987), Comparative Mythology, Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press, ISBN 0-8018-3938-6CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rogers, John H. (1998), "Origins of the Ancient Astronomical Constellations: I: The Mesopotamian Traditions", Journal of the British Astronomical Association, London, England: The British Astronomical Association, 108 (1): 9–28, Bibcode:1998JBAA..108....9RCS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Saggs, H. W. F. (1987), Everyday Life in Babylonia & Assyria, Dorset Press, ISBN 0-88029-127-3CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Schneider, Tammi J. (2011), An Introduction to Ancient Mesopotamian Religion, Grand Rapids, Michigan: William B. Eerdman's Publishing Company, ISBN 978-0-8028-2959-7CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sanders, Seth L. (2017), From Adapa to Enoch: Scribal Culture and Religious Vision in Judea and Babylonia, Tübingen, Germany: Mohr Siebeck, ISBN 978-3-16-154456-9CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Stephens, Kathryn (2013), "An/Anu (god): Mesopotamian sky-god, one of the supreme deities; known as An in Sumerian and Anu in Akkadian", Ancient Mesopotamian Gods and Goddesses, Open Richly Annotated Cuneiform Corpus, UK Higher Education AcademyCS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Stone, Adam (2016), "Enlil/Ellil (god)", Ancient Mesopotamian Gods and Goddesses, Open Richly Annotated Cuneiform Corpus, UK Higher Education AcademyCS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Van Scott, Miriam (1998), The Encyclopedia of Hell: A Comprehensive Survey of the Underworld, New York City, New York: Thomas Dunne Books/St. Martin's Griffin, ISBN 0-312-18574-XCS1 maint: ref=harv (link)