Inanna

| Inanna (Ishtar) | |

|---|---|

| |

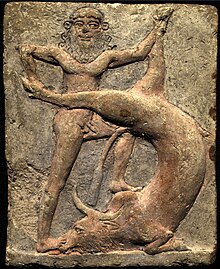

Goddess Ishtar on an Akkadian Empire seal, 2350-2150 BC. She is equipped with weapons on her back, has a horned helmet, and is trampling a lion. | |

| Abode | Heaven |

| Planet | Venus |

| Symbol | hook-shaped knot of reeds, eight-pointed star, lion, rosette, dove |

| Personal information | |

| Parents | |

| Siblings |

|

| Consort | Dumuzid the Shepherd and many unnamed others |

| Children | usually none, but sometimes Lulal and/or Shara |

| Equivalents | |

| Greek equivalent | Aphrodite, Athena[3][4][5] |

| Roman equivalent | Venus, Minerva[3][4][5] |

| Hinduism equivalent | Durga[6][7][8] |

| Canaanite equivalent | Astoreth |

| Babylonian equivalent | Ishtar |

Inanna[a] is an ancient Mesopotamian goddess associated with sex, war, justice, and political power. She was originally worshiped in Sumer and was later worshipped by the Akkadians, Babylonians, and Assyrians under the name Ishtar.[b] She was known as the "Queen of Heaven" and was the patron goddess of the Eanna temple at the city of Uruk, which was her main cult center. She was associated with the planet Venus and her most prominent symbols included the lion and the eight-pointed star. Her husband was the god Dumuzid (later known as Tammuz) and her sukkal, or personal attendant, was the goddess Ninshubur (who later became the male deity Papsukkal).

Inanna was worshiped in Sumer at least as early as the Uruk period (c. 4000 BC – c. 3100 BC), but she had little cult prior to the conquest of Sargon of Akkad. During the post-Sargonic era, she became one of the most widely venerated deities in the Sumerian pantheon,[11][12] with temples across Mesopotamia. The cult of Inanna-Ishtar, which may have been associated with a variety of sexual rites, was continued by the East Semitic-speaking people (Akkadians, Assyrians and Babylonians) who succeeded and absorbed the Sumerians in the region. She was especially beloved by the Assyrians, who elevated her to become the highest deity in their pantheon, ranking above their own national god Ashur. Inanna-Ishtar is alluded to in the Hebrew Bible and she greatly influenced the Phoenician goddess Astoreth, who later influenced the development of the Greek goddess Aphrodite. Her cult continued to flourish until its gradual decline between the first and sixth centuries AD in the wake of Christianity, though it survived in parts of Upper Mesopotamia among Assyrian communities as late as the eighteenth century.

Inanna appears in more myths than any other Sumerian deity.[13][14][15] Many of her myths involve her taking over the domains of other deities. She was believed to have stolen the mes, which represented all positive and negative aspects of civilization, from Enki, the god of wisdom. She was also believed to have taken over the Eanna temple from An, the god of the sky. Alongside her twin brother Utu (later known as Shamash), Inanna was the enforcer of divine justice; she destroyed Mount Ebih for having challenged her authority, unleashed her fury upon the gardener Shukaletuda after he raped her in her sleep, and tracked down the bandit woman Bilulu and killed her in divine retribution for having murdered Dumuzid. In the standard Akkadian version of the Epic of Gilgamesh, Ishtar asks Gilgamesh to become her consort. When he refuses, she unleashes the Bull of Heaven, resulting in the death of Enkidu and Gilgamesh's subsequent grapple with his mortality.

Inanna-Ishtar's most famous myth is the story of her descent into and return from Kur, the ancient Sumerian Underworld, a myth in which she attempts to conquer the domain of her older sister Ereshkigal, the queen of the Underworld, but is instead deemed guilty of hubris by the seven judges of the Underworld and struck dead. Three days later, Ninshubur pleads with all the gods to bring Inanna back, but all of them refuse her except Enki, who sends two sexless beings to rescue Inanna. They escort Inanna out of the Underworld, but the galla, the guardians of the Underworld, drag her husband Dumuzid down to the Underworld as her replacement. Dumuzid is eventually permitted to return to heaven for half the year while his sister Geshtinanna remains in the Underworld for the other half, resulting in the cycle of the seasons.

Etymology[edit]

Inanna and Ishtar were originally separate, unrelated deities,[17][18][1][19][20] but they were equated with each other during the reign of Sargon of Akkad and came to be regarded as effectively the same goddess under two different names.[17][18][1][19][20] Inanna's name may derive from the Sumerian phrase nin-an-ak, meaning "Lady of Heaven",[21][22] but the cuneiform sign for Inanna (𒈹) is not a ligature of the signs lady (Sumerian: nin; Cuneiform: 𒊩𒌆 SAL.TUG2) and sky (Sumerian: an; Cuneiform: 𒀭 AN).[22][21][23] These difficulties led some early Assyriologists to suggest that Inanna may have originally been a Proto-Euphratean goddess, possibly related to the Hurrian mother goddess Hannahannah, who was only later accepted into the Sumerian pantheon. This idea was supported by Inanna's youthfulness, and as well as the fact that, unlike the other Sumerian divinities, she seems to have initially lacked a distinct sphere of responsibilities.[22] The view that there was a Proto-Euphratean substrate language in Southern Iraq before Sumerian is not widely accepted by modern Assyriologists.[24]

The name Ishtar occurs as an element in personal names from both the pre-Sargonic and post-Sargonic eras in Akkad, Assyria, and Babylonia.[25] It is of Semitic derivation[26][25] and is probably etymologically related to the name of the West Semitic god Attar, who is mentioned in later inscriptions from Ugarit and southern Arabia.[26][25] The morning star may have been conceived as a male deity who presided over the arts of war and the evening star may have been conceived as a female deity who presided over the arts of love.[25] Among the Akkadians, Assyrians, and Babylonians, the name of the male god eventually supplanted the name of his female counterpart,[20] but, due to extensive syncretism with Inanna, the deity remained as female, despite the fact that her name was in the masculine form.[20]

Origins and development[edit]

Inanna has posed a problem for many scholars of ancient Sumer due to the fact that her sphere of power contained more distinct and contradictory aspects than that of any other deity.[28] Two major theories regarding her origins have been proposed.[29] The first explanation holds that Inanna is the result of a syncretism between several previously unrelated Sumerian deities with totally different domains.[29] The second explanation holds that Inanna was originally a Semitic deity who entered the Sumerian pantheon after it was already fully structured, and who took on all the roles that had not yet been assigned to other deities.[30]

As early as the Uruk period (c. 4000 – c. 3100 BC), Inanna was already associated with the city of Uruk.[1] During this period, the symbol of a ring-headed doorpost was closely associated with Inanna.[1] The famous Uruk Vase (found in a deposit of cult objects of the Uruk III period) depicts a row of naked men carrying various objects, including bowls, vessels, and baskets of farm products,[31] and bringing sheep and goats to a female figure facing the ruler.[32] The female stands in front of Inanna's symbol of the two twisted reeds of the doorpost,[32] while the male figure holds a box and stack of bowls, the later cuneiform sign signifying the En, or high priest of the temple.[33]

Seal impressions from the Jemdet Nasr period (c. 3100 – c. 2900 BC) show a fixed sequence of symbols representing various cities, including those of Ur, Larsa, Zabalam, Urum, Arina, and probably Kesh.[34] This list probably reflects the report of contributions to Inanna at Uruk from cities supporting her cult.[34] A large number of similar seals have been discovered from phase I of the Early Dynastic period (c. 2900 – c. 2350 BC) at Ur, in a slightly different order, combined with the rosette symbol of Inanna.[34] These seals were used to lock storerooms to preserve materials set aside for her cult.[34]

During the Akkadian period (c. 2334 – 2154 BC), following the conquests of Sargon of Akkad, Inanna and Ishtar became so extensively syncretized that they became regarded as effectively the same.[18][20] The Akkadian poet Enheduanna, the daughter of Sargon, wrote numerous hymns to Inanna, identifying her with Ishtar.[18][35] Sargon himself proclaimed Inanna and An as the sources of his authority.[36] As a result of this,[18] the popularity of Inanna-Ishtar's cult skyrocketed.[18][1][19]

Worship[edit]

During the Pre-Sargonic era, the cult of Inanna was rather limited,[18] but, after the reign of Sargon, she quickly became one of the most widely venerated deities in the Sumerian pantheon.[18][15][23][12] She had temples in Nippur, Lagash, Shuruppak, Zabalam, and Ur,[18] but her main cult center was the Eanna temple in Uruk,[18][41][22][c] whose name means "House of Heaven" (Sumerian: e2-anna; Cuneiform: 𒂍𒀭 E2.AN),[d] The original patron deity of this fourth-millennium BC city was probably An.[22] After its dedication to Inanna, the temple seems to have housed priestesses of the goddess.[22] During later times, while her cult in Uruk continued to flourish,[43] Ishtar also became particularly worshipped in the Upper Mesopotamian kingdom of Assyria (modern northern Iraq, northeast Syria and southeast Turkey), especially in the cities of Nineveh, Aššur and Arbela (modern Erbil).[44] During the reign of the Assyrian king Assurbanipal, Ishtar rose to become the most important and widely venerated deity in the Assyrian pantheon, surpassing even the Assyrian national god Ashur.[43]

As Ishtar became more prominent, several lesser or regional deities were assimilated into her,[45] including Aya (the wife of Utu), Anatu (Antu, a consort of Anu), Anunitu (an Akkadian light goddess), Agasayam (a warrior goddess), Irnini (the goddess of cedar forests in the Lebanese mountains), Kilili or Kulili (the symbol of desirable women), Sahirtu (the messenger of lovers), Kir-gu-lu (the bringer of rain), and Sarbanda (the personification of sovereignty).[45]

Androgynous and hermaphroditic men were heavily involved in the cult of Inanna-Ishtar.[46] During Sumerian times, a set of priests known as gala worked in Inanna's temples, where they performed elegies and lamentations.[47] Gala took female names, spoke in the eme-sal dialect, which was traditionally reserved for women, and appear to have engaged in homosexual intercourse.[48] During the Akkadian Period, kurgarrū and assinnu were servants of Ishtar who dressed in female clothing and performed war dances in Ishtar's temples.[49] Several Akkadian proverbs seem to suggest that they may have also had homosexual proclivities.[49] Gwendolyn Leick, an anthropologist known for her writings on Mesopotamia, has compared these individuals to the contemporary Indian hijra.[50] In one Akkadian hymn, Ishtar is described as transforming men into women.[51]

According to the early scholar Samuel Noah Kramer, towards the end of the third millennium BC, kings of Uruk may have established their legitimacy by taking on the role of the shepherd Dumuzid, Inanna's consort.[52] This ritual lasted for one night on the tenth day of the Akitu,[52][53] the Sumerian new year festival,[53] which was celebrated annually at the spring equinox.[52] The king would then partake in a "sacred marriage" ceremony,[52] during which he engaged in ritual sexual intercourse with the high priestess of Inanna, who took on the role of the goddess.[52][53] In the late twentieth century, the historicity of the sacred marriage ritual was treated by scholars as more-or-less an established fact,[54] but, largely due to the writings of Pirjo Lapinkivi, many have begun to regard the sacred marriage as a literary invention rather than an actual ritual.[54]

The cult of Ishtar was long thought to have involved sacred prostitution,[55][56][44][57] but this is now rejected among many scholars.[58][59][60][61] Hierodules known as ishtaritum are reported to have worked in Ishtar's temples,[56] but it is unclear if such priestesses actually performed any sex acts[59] and several modern scholars have argued that they did not.[60][58] Women across the ancient Near East worshipped Ishtar by dedicating to her cakes baked in ashes (known as kamān tumri).[62] A dedication of this type is described in an Akkadian hymn.[63] Several clay cake molds discovered at Mari are shaped like naked women with large hips clutching their breasts.[63] Some scholars have suggested that the cakes made from these molds were intended as representations of Ishtar herself.[64]

Iconography[edit]

Symbols[edit]

Inanna-Ishtar's most common symbol was the eight-pointed star,[65] though the exact number of points sometimes varies.[66] Six-pointed stars also occur frequently, but their symbolic meaning is unknown.[70] The eight-pointed star seems to have originally borne a general association with the heavens,[71] but, by the Old Babylonian Period (c. 1830 – c. 1531 BC), it had come to be specifically associated with the planet Venus, with which Ishtar was identified.[71] Starting during this same period, the star of Ishtar was normally enclosed within a circular disc.[70] During later Babylonian times, slaves who worked in Ishtar's temples were sometimes branded with the seal of the eight-pointed star.[70][72] On boundary stones and cylinder seals, the eight-pointed star is sometimes shown alongside the crescent moon, which was the symbol of Sin (Sumerian Nanna) and the rayed solar disk, which was a symbol of Shamash (Sumerian Utu).[73][66]

Inanna's cuneiform ideogram was a hook-shaped twisted knot of reeds, representing the doorpost of the storehouse, a common symbol of fertility and plenty.[74] The rosette was another important symbol of Inanna, which continued to be used as a symbol of Ishtar after their syncretism.[75] During the Neo-Assyrian Period (911 – 609 BC), the rosette may have actually eclipsed the eight-pointed star and become Ishtar's primary symbol.[76] The temple of Ishtar in the city of Aššur was adorned with numerous rosettes.[75]

Inanna-Ishtar was associated with lions,[67][68] which the ancient Mesopotamians regarded as a symbol of power.[67] Her associations with lions began during Sumerian times;[68] a chlorite bowl from the temple of Inanna at Nippur depicts a large feline battling a giant snake and a cuneiform inscription on the bowl reads "Inanna and the Serpent," indicating that the cat is supposed to represent the goddess.[68] During the Akkadian Period, Ishtar was frequently depicted as a heavily armed warrior goddess with a lion as one of her attributes.[77]

Doves were also prominent animal symbols associated with Inanna-Ishtar.[78][79] Doves are shown on cultic objects associated with Inanna as early as the beginning of the third millennium BC.[79] Lead dove figurines were discovered in the temple of Ishtar at Aššur, dating to the thirteenth century BC[79] and a painted fresco from Mari, Syria shows a giant dove emerging from a palm tree in the temple of Ishtar,[78] indicating that the goddess herself was sometimes believed to take the form of a dove.[78]

As the planet Venus[edit]

Inanna was associated with the planet Venus, which is named after her Roman equivalent Venus.[41][80][41] Several hymns praise Inanna in her role as the goddess or personification of the planet Venus.[81] Theology professor Jeffrey Cooley has argued that, in many myths, Inanna's movements may correspond with the movements of the planet Venus in the sky.[81] In Inanna's Descent to the Underworld, unlike any other deity, Inanna is able to descend into the netherworld and return to the heavens. The planet Venus appears to make a similar descent, setting in the West and then rising again in the East.[81] An introductory hymn describes Inanna leaving the heavens and heading for Kur, what could be presumed to be, the mountains, replicating the rising and setting of Inanna to the West.[81] In Inanna and Shukaletuda, Shukaletuda is described as scanning the heavens in search of Inanna, possibly searching the eastern and western horizons.[82] In the same myth, while searching for her attacker, Inanna herself makes several movements that correspond with the movements of Venus in the sky.[81]

Because the movements of Venus appear to be discontinuous (it disappears due to its proximity to the sun, for many days at a time, and then reappears on the other horizon), some cultures did not recognize Venus as single entity;[81] instead, they assumed it to be two separate stars on each horizon: the morning and evening star.[81] Nonetheless, a cylinder seal from the Jemdet Nasr period indicates that the ancient Sumerians already knew that the morning and evening stars were the same celestial object.[81] The discontinuous movements of Venus relate to both mythology as well as Inanna's dual nature.[81]

Inanna in her aspect as Anunītu was associated with the eastern fish of the last of the zodiacal constellations, Pisces.[83][84] Her consort Dumuzi was associated with the contiguous first constellation, Aries.[83]

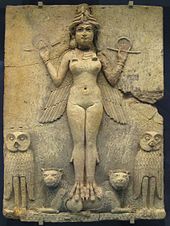

Babylonian terracotta relief of Ishtar from Eshnunna (early second millennium BC)

Life-sized statue of a goddess, probably Ishtar, holding a vase from Mari, Syria (eighteenth century BC)

Terracotta relief of Ishtar with wings from Larsa (second millennium BC)

Stele showing Ishtar holding a bow from Ennigaldi-Nanna's museum (eighth century BC)

Hellenized bas-relief sculpture of Ishtar standing with her servant from Palmyra (third century AD)

Character[edit]

The Sumerians worshipped Inanna as the goddess of both warfare and sexuality.[1] Unlike other gods, whose roles were static and whose domains were limited, the stories of Inanna describe her as moving from conquest to conquest.[28][87] She was portrayed as young and impetuous, constantly striving for more power than she had been allotted.[28][87]

Although she was worshipped as the goddess of love, Inanna was not the goddess of marriage, nor was she ever viewed as a mother goddess.[88][89] A description of her from one of her hymns declares, "When the servants let the flocks loose, and when cattle and sheep are returned to cow-pen and sheepfold, then, my lady, like the nameless poor, you wear only a single garment. The pearls of a prostitute are placed around your neck, and you are likely to snatch a man from the tavern."[90] In Inanna's Descent to the Underworld, Inanna treats her lover Dumuzid in a very capricious manner.[88] This aspect of Inanna's personality is emphasized in the later standard Akkadian version of the Epic of Gilgamesh in which Gilgamesh points out Ishtar's infamous ill-treatment of her lovers.[91][92]

Inanna was also worshipped as one of the Sumerian war deities.[41][93] One of her hymns declares: "She stirs confusion and chaos against those who are disobedient to her, speeding carnage and inciting the devastating flood, clothed in terrifying radiance. It is her game to speed conflict and battle, untiring, strapping on her sandals."[94] Battle itself was occasionally referred to as the "Dance of Inanna".[95]

Family[edit]

Inanna's twin brother was Utu, the god of the sun and justice (who was later known as Shamash in East Semitic languages).[97][98][99] In Sumerian texts, Inanna and Utu are shown as extremely close;[100] in fact, their relationship frequently borders on incestuous.[100][101] Inanna's sukkal is the goddess Ninshubur,[102] whose relationship with Inanna is one of mutual devotion.[102] In the myth of her descent into the Underworld, Inanna addresses Ereshkigal, the queen of the underworld, as her "older sister",[103][104] but the two goddesses almost never appear together in Sumerian literature.[104] In Uruk, Inanna was usually regarded as the daughter of the sky god An,[1][2] but, in the Isin tradition, she is usually described as the daughter of the moon god Nanna (who was later known as Sin).[105][2][1] In literary texts, she is sometimes described as the daughter of Enlil[1][2] or the daughter of Enki.[1][2] In some later stories, Inanna-Ishtar is the sister of Ishkur (Hadad), the god of storms,[106] and, in Hittite mythology, Ishtar is the sister of Teshub, the Hittite storm god.[107]

Dumuzid (later known as Tammuz), the god of shepherds, is usually described as Inanna's husband,[98] but Inanna's loyalty to him is questionable;[1] in the myth of her descent into the Underworld, she abandons Dumuzid and permits the galla demons to drag him down into the Underworld as her replacement,[108][109] but in the later myth of The Return of Dumuzid Inanna paradoxically mourns over Dumuzid's death and ultimately decrees that he will be allowed to return to Heaven to be with her for one half of the year.[110][109] Inanna is not usually described as having any offspring,[1] but, in the myth of Lugalbanda and in a single building inscription from the Third Dynasty of Ur (c. 2112 – c. 2004 BC), the warrior god Shara is described as her son.[111] She was also sometimes considered the mother of Lulal,[112] who is described in other texts as the son of Ninsun.[112]

Sumerian mythology[edit]

Origin myths[edit]

The poem of Enki and the World Order (ETCSL 1.1.3) begins by describing the god Enki and his establishment of the cosmic organization of the universe.[113] Towards the end of the poem, Inanna comes to Enki and complains that he has assigned a domain and special powers to all of the other gods except for her.[114] She declares that she has been treated unfairly.[115] Enki responds by telling her that she already has a domain and that he does not need to assign her one.[116]

The myth of "Inanna and the Huluppu Tree", found in the preamble to the epic of Gilgamesh, Enkidu, and the Netherworld (ETCSL 1.8.1.4),[117] centers around a young Inanna, not yet stable in her power.[118][119] It begins with a huluppu tree, which Kramer identifies as possibly a willow,[120] growing on the banks of the river Euphrates.[120][121][122] Inanna moves the tree to her garden in Uruk with the intention to carve it into a throne once it is fully grown.[120][121][122] The tree grows and matures, but the serpent "who knows no charm," the Anzû-bird, and Lilitu, the Sumerian forerunner to the Lilith of Jewish folklore, all take up residence within the tree, causing Inanna to cry with sorrow.[120][121][122] The hero Gilgamesh, who, in this story, is portrayed as her brother, comes along and slays the serpent, causing the Anzû-bird and Lilitu to flee.[123][121][122] Gilgamesh's companions chop down the tree and carve its wood into a bed and a throne, which they give to Inanna,[124][121][122] who fashions a pikku and a mikku (probably a drum and drumsticks respectively, although the exact identifications are uncertain),[125] which she gives to Gilgamesh as a reward for his heroism.[126][121][122]

The Sumerian hymn Inanna and Utu contains an etiological myth describing how Inanna became the goddess of sex.[127] At the beginning of the hymn, Inanna knows nothing of sex,[127] so she begs her brother Utu to take her to Kur (the Sumerian Underworld),[127] so that she may taste the fruit of a tree that grows there,[127] which will reveal to her all the secrets of sex.[127] Utu complies and, in Kur, Inanna tastes the fruit and becomes knowledgeable.[127] The hymn employs the same motif found in the myth of Enki and Ninhursag and in the later Biblical story of Adam and Eve.[127]

The poem Inanna Prefers the Farmer (ETCSL 4.0.8.3.3) begins with a rather playful conversation between Inanna and Utu, who incrementally reveals to her that it is time for her to marry.[15][128] She is courted by a farmer named Enkimdu and a shepherd named Dumuzid.[15] At first, Inanna prefers the farmer,[15] but Utu and Dumuzid gradually persuade her that Dumuzid is the better choice for a husband, arguing that, for every gift the farmer can give to her, the shepherd can give her something even better.[129] In the end, Inanna marries Dumuzid.[129] The shepherd and the farmer reconcile their differences, offering each other gifts.[130] Samuel Noah Kramer compares the myth to the later Biblical story of Cain and Abel because both myths center around a farmer and a shepherd competing for divine favor and, in both stories, the deity in question ultimately chooses the shepherd.[15]

Conquests and patronage[edit]

Inanna and Enki (ETCSL t.1.3.1) is a lengthy poem written in Sumerian, which may date to the Third Dynasty of Ur (c. 2112 BC – c. 2004 BC);[132] it tells the story of how Inanna stole the sacred mes from Enki, the god of water and human culture.[133] In ancient Sumerian mythology, the mes were sacred powers or properties belonging the gods that allowed human civilization to exist.[134] Each me embodied one specific aspect of human culture.[134] These aspects were very diverse and the mes listed in the poem include abstract concepts such as Truth, Victory, and Counsel, technologies such as writing and weaving, and also social constructs such as law, priestly offices, kingship, and prostitution. The mes were believed to grant power over all the aspects of civilization, both positive and negative.[133]

In the myth, Inanna travels from her own city of Uruk to Enki's city of Eridu, where she visits his temple, the E-Abzu.[135] Inanna is greeted by Enki's sukkal, Isimud, who offers her food and drink.[136][137] Inanna starts up a drinking competition with Enki.[133][138] Then, once Enki is thoroughly intoxicated, Inanna persuades him to give her the mes.[133][139] Inanna flees from Eridu in the Boat of Heaven, taking the mes back with her to Uruk.[140][141] Enki wakes up to discover that the mes are gone and asks Isimud what has happened to them.[140][142] Isimud replies that Enki has given all of them to Inanna.[143][144] Enki becomes infuriated and sends multiple sets of fierce monsters after Inanna to take back the mes before she reaches the city of Uruk.[145][146] Inanna's sukkal Ninshubur fends off all of the monsters that Enki sends after them.[147][148][102] Through Ninshubur's aid, Inanna successfully manages to take the mes back with her to the city of Uruk.[147][149] After Inanna escapes, Enki reconciles with her and bids her a positive farewell.[150] It is possible that this legend may represent a historic transfer of power from the city of Eridu to the city of Uruk.[22][151] It is also possible that this legend may be a symbolic representation of Inanna's maturity and her readiness to become the Queen of Heaven.[152]

The poem Inanna Takes Command of Heaven is an extremely fragmentary, but important, account of Inanna's conquest of the Eanna temple in Uruk.[22] It begins with a conversation between Inanna and her brother Utu in which Inanna laments that the Eanna temple is not within their domain and resolves to claim it as her own.[22] The text becomes increasingly fragmentary at this point in the narrative,[22] but appears to describe her difficult passage through a marshland to reach the temple while a fisherman instructs her on which route is best to take.[22] Ultimately, Inanna reaches her father An, who is shocked by her arrogance, but nevertheless concedes that she has succeeded and that the temple is now her domain.[22] The text ends with a hymn expounding Inanna's greatness.[22] This myth may represent an eclipse in the authority of the priests of An in Uruk and a transfer of power to the priests of Inanna.[22]

Inanna briefly appears at the beginning and end of the epic poem Enmerkar and the Lord of Aratta (ETCSL 1.8.2.3). The epic deals with a rivalry between the cities of Uruk and Aratta. Enmerkar, the king of Uruk, wishes to adorn his city with jewels and precious metals, but cannot do so because such minerals are only found in Aratta and, since trade does not yet exist, the resources are not available to him.[153] Inanna, who is the patron goddess of both cities,[154] appears to Enmerkar at the beginning of the poem[155] and tells him that she favors Uruk over Aratta.[156] She instructs Enmerkar to send a messenger to the lord of Aratta to ask for the resources Uruk needs.[154] The majority of the epic revolves around a great contest between the two kings over Inanna's favor.[157] Inanna reappears at the end of the poem to resolve the conflict by telling Enmerkar to establish trade between his city and Aratta.[158]

Justice myths[edit]

Inanna and her brother Utu were regarded as the dispensers of divine justice,[100] a role which Inanna exemplifies in several of her myths.[159] Inanna and Ebih (ETCSL 1.3.2), otherwise known as Goddess of the Fearsome Divine Powers, is a 184-line poem written by the Akkadian poet Enheduanna describing Inanna's confrontation with Mount Ebih, a mountain in the Zagros mountain range.[160] The poem begins with an introductory hymn praising Inanna.[161] The goddess journeys all over the entire world, until she comes across Mount Ebih and becomes infuriated by its glorious might and natural beauty,[162] considering its very existence as an outright affront to her own authority.[163][160] She rails at Mount Ebih, shouting:

Mountain, because of your elevation, because of your height,

Because of your goodness, because of your beauty,

Because you wore a holy garment,

Because An organized(?) you,

Because you did not bring (your) nose close to the ground,

Because you did not press (your) lips in the dust.[164]

Inanna petitions to An, the Sumerian god of the heavens, to allow her to destroy Mount Ebih.[162] An warns Inanna not to attack the mountain,[162] but she ignores his warning and proceeds to attack and destroy Mount Ebih regardless.[162] In the conclusion of the myth, she explains to Mount Ebih why she attacked it.[164] In Sumerian poetry, the phrase "destroyer of Kur" is occasionally used as one of Inanna's epithets.[165]

The poem Inanna and Shukaletuda (ETCSL 1.3.3) begins with a hymn to Inanna, praising her as the planet Venus.[166] It then introduces Shukaletuda, a gardener who is terrible at his job and partially blind. All of his plants die, except for one poplar tree.[166] Shukaletuda prays to the gods for guidance in his work. To his surprise, the goddess Inanna sees his one poplar tree and decides to rest under the shade of its branches.[166] Shukaletuda removes her clothes and rapes Inanna while she sleeps.[166] When the goddess wakes up and realizes she has been violated, she becomes furious and determines to bring her attacker to justice.[166] In a fit of rage, Inanna unleashes horrible plagues upon the Earth, turning water into blood.[166] Shukaletuda, terrified for his life, pleads his father for advice on how to escape Inanna's wrath.[166] His father tells him to hide in the city, amongst the hordes of people, where he will hopefully blend in.[166] Inanna searches the mountains of the East for her attacker,[166] but is not able to find him.[166] She then releases a series of storms and closes all roads to the city, but is still unable to find Shukaletuda,[166] so she asks Enki to help her find him, threatening to leave her temple in Uruk if he does not.[166] Enki consents and allows Inanna to "fly across the sky like a rainbow".[166] Inanna finally locates Shukaletuda, who vainly attempts to invent excuses for his crime against her. Inanna rejects these excuses and kills him.[167] Theology professor Jeffrey Cooley has cited the story of Shukaletuda as a Sumerian astral myth, arguing that the movements of Inanna in the story correspond with the movements of the planet Venus.[81] He has also stated that, while Shukaletuda was praying to the goddess, he may have been looking toward Venus on the horizon.[167]

The text of the poem Inanna and Bilulu (ETCSL 1.4.4), discovered at Nippur, is badly mutilated[168] and scholars have interpreted it in a number of different ways.[168] The beginning of the poem is mostly destroyed,[168] but seems to be a lament.[168] The intelligible part of the poem describes Inanna pining after her husband Dumuzid, who is in the steppe watching his flocks.[168][169] Inanna sets out to find him.[168] After this, a large portion of the text is missing.[168] When the story resumes, Inanna is being told that Dumuzid has been murdered.[168] Inanna discovers that the old bandit woman Bilulu and her son Girgire are responsible.[170][169] She travels along the road to Edenlila and stops at an inn, where she finds the two murderers.[168] Inanna stands on top of a stool[168] and transforms Bilulu into "the waterskin that men carry in the desert",[168][171][170][169] forcing her to pour the funerary libations for Dumuzid.[168][169]

Descent into the underworld[edit]

Two different versions of the story of Inanna-Ishtar's descent into the underworld have survived:[172][173] a Sumerian version dating to the Third Dynasty of Ur (ETCSL 1.4.1)[172][173] and a clearly derivative Akkadian version from the early second millennium BC.[172][173] The Sumerian version of the story is nearly three times the length of the later Akkadian version and contains much greater detail.[174]

Sumerian version[edit]

In Sumerian religion, the Kur was conceived of as a dark, dreary cavern located deep underground;[175] life there was envisioned as "a shadowy version of life on earth".[175] It was ruled by Inanna's sister, the goddess Ereshkigal.[103][175] Before leaving, Inanna instructs her minister and servant Ninshubur to plead with the deities Enlil, Nanna, Anu, and Enki to rescue her if she does not return after three days.[176][177] The laws of the underworld dictate that, with the exception of appointed messengers, those who enter it may never leave.[176] Inanna dresses elaborately for the visit; she wears a turban, wig, lapis lazuli necklace, beads upon her breast, the 'pala dress' (the ladyship garment), mascara, a pectoral, and golden ring, and holds a lapis lazuli measuring rod.[178][179] Each garment is a representation of a powerful me she possesses.[180]

Inanna pounds on the gates of the underworld, demanding to be let in.[181][182][177] The gatekeeper Neti asks her why she has come[181][183] and Inanna replies that she wishes to attend the funeral rites of Gugalanna, the "husband of my elder sister Ereshkigal".[103][181][183] Neti reports this to Ereshkigal,[184][185] who tells him: "Bolt the seven gates of the underworld. Then, one by one, open each gate a crack. Let Inanna enter. As she enters, remove her royal garments."[186] Perhaps Inanna's garments, unsuitable for a funeral, along with Inanna's haughty behavior, make Ereshkigal suspicious.[187] Following Ereshkigal's instructions, Neti tells Inanna she may enter the first gate of the underworld, but she must hand over her lapis lazuli measuring rod. She asks why, and is told, "It is just the ways of the underworld." She obliges and passes through. Inanna passes through a total of seven gates, at each one removing a piece of clothing or jewelry she had been wearing at the start of her journey,[188] thus stripping her of her power.[189][177] When she arrives in front of her sister, she is naked:[189][177]

"After she had crouched down and had her clothes removed, they were carried away. Then she made her sister Erec-ki-gala rise from her throne, and instead she sat on her throne. The Anna, the seven judges, rendered their decision against her. They looked at her – it was the look of death. They spoke to her – it was the speech of anger. They shouted at her – it was the shout of heavy guilt. The afflicted woman was turned into a corpse. And the corpse was hung on a hook."[190]

Three days and three nights pass, and Ninshubur, following instructions, goes to the temples of Enlil, Nanna, An, and Enki, and pleads with each of them to rescue Inanna.[191][192][193] The first three deities refuse, saying Inanna's fate is her own fault,[191][194][195] but Enki is deeply troubled and agrees to help.[196][197][195] He creates two sexless figures named gala-tura and the kur-jara from the dirt under the fingernails of two of his fingers.[196][198][195] He instructs them to appease Ereshkigal[196][198] and, when she asks them what they want, ask for the corpse of Inanna, which they must sprinkle with the food and water of life.[196][198] When they come before Ereshkigal, she is in agony like a woman giving birth.[199] She offers them whatever they want, including life-giving rivers of water and fields of grain, if they can relieve her,[200] but they refuse all of her offers and ask only for Inanna's corpse.[199] The gala-tura and the kur-jara sprinkle Inanna's corpse with the food and water of life and revive her.[201][202][195] Galla demons sent by Ereshkigal follow Inanna out of the underworld, insisting that someone else must be taken to the underworld as Inanna's replacement.[203][204][195] They first come upon Ninshubur and attempt to take her,[203][204][195] but Inanna stops them, insisting that Ninshubur is her loyal servant and that she had rightfully mourned for her while she was in the underworld.[203][204][195] They next come upon Shara, Inanna's beautician, who is still in mourning.[205][206][195] The demons attempt to take him, but Inanna insists that they may not, because he had also mourned for her.[207][208][195] The third person they come upon is Lulal, who is also in mourning.[207][209][195] The demons try to take him, but Inanna stops them once again.[207][209][195]

Finally, they come upon Dumuzid, Inanna's husband.[210][195] Despite Inanna's fate, and in contrast to the other individuals who were properly mourning her, Dumuzid is lavishly clothed and resting beneath a tree, or upon her throne, entertained by slave-girls. Inanna, displeased, decrees that the galla shall take him.[210][195][211] The galla then drag Dumuzid down to the underworld.[210][195] Another text known as Dumuzid's Dream (ETCSL 1.4.3) describes Dumuzid's repeated attempts to evade capture by the galla demons, an effort in which he is aided by the sun-god Utu.[212][213][e]

In the Sumerian poem The Return of Dumuzid, which begins where The Dream of Dumuzid ends, Dumuzid's sister Geshtinanna laments continually for days and nights over Dumuzid's death, joined by Inanna, who has apparently experienced a change of heart, and Sirtur, Dumuzid's mother.[214] The three goddesses mourn continually until a fly reveals to Inanna the location of her husband.[215] Together, Inanna and Geshtinanna go to the place where the fly has told them they will find Dumuzid.[216] They find him there and Inanna decrees that, from that point onwards, Dumuzid will spend half of the year with her sister Ereshkigal in the underworld and the other half of the year in Heaven with her, while his sister Geshtinanna takes his place in the underworld.[217][195][218]

Akkadian version[edit]

The Akkadian version begins with Ishtar approaching the gates of the underworld and demanding the gatekeeper to let her in:

If you do not open the gate for me to come in,

I shall smash the door and shatter the bolt,

I shall smash the doorpost and overturn the doors,

I shall raise up the dead and they shall eat the living:

And the dead shall outnumber the living![219]

The gatekeeper (whose name is not given in the Akkadian version[219]) hurries to tell Ereshkigal of Ishtar's arrival. Ereshkigal orders him to let Ishtar enter, but tells him to "treat her according to the ancient rites."[220] The gatekeeper lets Ishtar into the underworld, opening one gate at a time.[220] At each gate, Ishtar is forced to shed one article of clothing. When she finally passes the seventh gate, she is naked.[221] In a rage, Ishtar throws herself at Ereshkigal, but Ereshkigal orders her servant Namtar to imprison Ishtar and unleash sixty diseases against her.[222]

After Ishtar descends to the underworld, all sexual activity ceases on earth.[223] The god Papsukkal, the Akkadian counterpart to Ninshubur,[224] reports the situation to Ea, the god of wisdom and culture.[223] Ea creates an intersex being called Asu-shu-namir and sends them to Ereshkigal, telling them to invoke "the name of the great gods" against her and to ask for the bag containing the waters of life. Ereshkigal becomes enraged when she hears Asu-shu-namir's demand, but she is forced to give them the water of life. Asu-shu-namir sprinkles Ishtar with this water, reviving her. Then, Ishtar passes back through the seven gates, receiving one article of clothing back at each gate, and exiting the final gate fully clothed.[223]

Interpretations[edit]

Folklorist Diane Wolkstein interprets the myth as a union between Inanna and her own "dark side": her twin sister-self, Ereshkigal. When Inanna ascends from the underworld, it is through Ereshkigal's powers, but, while Inanna is in the underworld, it is Ereshkigal who apparently takes on the powers of fertility. The poem ends with a line in praise, not of Inanna, but of Ereshkigal. Wolkstein interprets the narrative as a praise-poem dedicated to the more negative aspects of Inanna's domain, symbolic of an acceptance of the necessity of death in order to facilitate the continuance of life.[225] Joseph Campbell interprets the myth as being about the psychological power of a descent into the unconscious, the realization of one's own strength through an episode of seeming powerlessness, and the acceptance of one's own negative qualities.[226]

Conversely, Joshua Mark argues that the most likely moral intended by the original author of the Descent of Inanna is that there are always consequences for one's actions: "The Descent of Inanna, then, about one of the gods behaving badly and other gods and mortals having to suffer for that behavior, would have given to an ancient listener the same basic understanding anyone today would take from an account of a tragic accident caused by someone’s negligence or poor judgment: that, sometimes, life is just not fair."[17]

Another recent interpretation, by Clyde Hostetter, holds that the myth is an allegorical report of related movements of the planets Venus, Mercury, and Jupiter;[227] and those of the waxing crescent Moon in the Second Millennium, beginning with the spring equinox and concluding with a meteor shower near the end of one synodic period of Venus.[227] The three-day disappearance of Inanna refers to the three-day planetary disappearance of Venus between its appearance as a morning or evening star.[227] The fact that Gugalana is slain refers to the disappearance of the constellation Taurus when the sun rises in that part of the sky, which in the Bronze Age marked the occurrence of the vernal equinox.[227]

Later myths[edit]

Epic of Gilgamesh[edit]

In the Akkadian Epic of Gilgamesh, Ishtar appears to Gilgamesh after he and his companion Enkidu have returned to Uruk from defeating the ogre Humbaba and demands Gilgamesh to become her consort.[229] Gilgamesh refuses her, pointing out that all of her previous lovers have suffered:[229]

Listen to me while I tell the tale of your lovers. There was Tammuz, the lover of your youth, for him you decreed wailing, year after year. You loved the many-coloured Lilac-breasted Roller, but still you struck and broke his wing [...] You have loved the lion tremendous in strength: seven pits you dug for him, and seven. You have loved the stallion magnificent in battle, and for him you decreed the whip and spur and a thong [...] You have loved the shepherd of the flock; he made meal-cake for you day after day, he killed kids for your sake. You struck and turned him into a wolf; now his own herd-boys chase him away, his own hounds worry his flanks."[230]

Infuriated by Gilgamesh's refusal,[229] Ishtar goes to heaven and tells her father Anu that Gilgamesh has insulted her.[229] Anu asks her why she is complaining to him instead of confronting Gilgamesh herself.[229] Ishtar demands that Anu give her the Bull of Heaven[229] and swears that if he does not give it to her, she will "break in the doors of hell and smash the bolts; there will be confusion [i.e., mixing] of people, those above with those from the lower depths. I shall bring up the dead to eat food like the living; and the hosts of the dead will outnumber the living."[231]

Anu gives Ishtar the Bull of Heaven, and Ishtar sends it to attack Gilgamesh and his friend Enkidu.[228][232] Gilgamesh and Enkidu kill the Bull and offer its heart to the sun-god Shamash.[233][232] While Gilgamesh and Enkidu are resting, Ishtar stands up on the walls of Uruk and curses Gilgamesh.[233][234] Enkidu tears off the Bull's right thigh and throws it in Ishtar's face,[233][234] saying, "If I could lay my hands on you, it is this I should do to you, and lash your entrails to your side."[235] (Enkidu later dies for this impiety.)[234] Ishtar calls together "the crimped courtesans, prostitutes and harlots"[233] and orders them to mourn for the Bull of Heaven.[233][234] Meanwhile, Gilgamesh holds a celebration over the Bull of Heaven's defeat.[236][234]

Later in the epic, Utnapishtim tells Gilgamesh the story of the Great Flood,[237] which was sent by the god Enlil to annihilate all life on earth because the humans, who were vastly overpopulated, made too much noise and prevented him from sleeping.[238] Utnapishtim tells how, when the flood came, Ishtar wept and mourned over the destruction of humanity, alongside the Anunnaki.[239] Later, after the flood subsides, Utnapishtim makes an offering to the gods.[240] Ishtar appears to Utnapishtim wearing a lapis lazuli necklace with beads shaped like flies and tells him that Enlil never discussed the flood with any of the other gods.[241] She swears him that she will never allow Enlil to cause another flood[242] and declares her lapis lazuli necklace a sign of her oath.[241] Ishtar invites all the gods except for Enlil to gather around the offering and enjoy.[243]

Other tales[edit]

In the Hittite Creation myth, Ishtar is born after the god Kumarbi overthrows his father Anu.[107] Kumarbi bites off Anu's genitals and swallows them,[107] causing him to become pregnant with Anu's offspring,[107] including Ishtar and her brother, the Hittite storm god Teshub.[107] This account later became the basis for the Greek story of Uranus's castration by his son Cronus, resulting in the birth of Aphrodite, described in Hesiod's Theogony.[244] Later in the Hittite myth, Ishtar attempts to seduce the monster Ullikummi,[107] but fails because the monster is both blind and deaf and is unable to see or hear her.[107] The Hurrians and Hittites appear to have syncretized Ishtar with their own goddess Išḫara.[245][246] In a pseudepigraphical Neo-Assyrian text written in the seventh century BCE, but which claims to be the autobiography of Sargon of Akkad,[247] Ishtar is claimed to have appeared to Sargon "surrounded by a cloud of doves" while he was working as a gardener for Akki, the drawer of the water.[247] Ishtar then proclaimed Sargon her lover and allowed him to become the ruler of Sumer and Akkad.[247]

Later influence[edit]

In antiquity[edit]

The cult of Inanna-Ishtar may have been introduced to the Kingdom of Judah during the reign of King Manasseh[250] and, although Inanna herself is not directly mentioned in the Bible by name,[251] the Old Testament contains numerous allusions to her cult.[252] Jeremiah 7:18 and Jeremiah 44:15-19 mention "the Queen of Heaven", who is probably a syncretism of Inanna-Ishtar and the West Semitic goddess Astarte.[250][253][254][62] Jeremiah states that the Queen of Heaven was worshipped by women who baked cakes for her.[64]

The Song of Songs bears strong similarities to the Sumerian love poems involving Inanna and Dumuzid,[255] particularly in its usage of natural symbolism to represent the lovers' physicality.[255] Song of Songs 6:10 ("Who is she that looketh forth as the morning, fair as the moon, clear as the sun, and terrible as an army with banners?") is almost certainly a reference to Inanna-Ishtar.[8] Ezekiel 8:14 mentions Inanna's husband Dumuzid under his later East Semitic name Tammuz[256][257][258] and describes a group of women mourning Tammuz's death while sitting near the north gate of the Temple in Jerusalem.[257][258]

The cult of Inanna-Ishtar also heavily influenced the cult of the Phoenician goddess Astoreth.[259] The Phoenicians introduced Astarte to the Greek islands of Cyprus and Cythera,[253][260] where she either gave rise to or heavily influenced the Greek goddess Aphrodite.[261][260][244][259] Aphrodite took on Inanna-Ishtar's associations with sexuality and procreation.[262][263] Furthermore, she was known as Ourania (Οὐρανία), which means "heavenly",[264][263] a title corresponding to Inanna's role as the Queen of Heaven.[264][263]

Early artistic and literary portrayals of Aphrodite are extremely similar to Inanna-Ishtar.[262][263] Aphrodite was also a warrior goddess;[262][260][265] the second-century AD Greek geographer Pausanias records that, in Sparta, Aphrodite was worshipped as Aphrodite Areia, which means "warlike".[266][267] He also mentions that Aphrodite's most ancient cult statues in Sparta and on Cythera showed her bearing arms.[266][267][268][262] Modern scholars note that Aphrodite's warrior-goddess aspects appear in the oldest strata of her worship[269] and see it as an indication of her Near Eastern origins.[269][265] Aphrodite also absorbed Ishtar's association with doves,[78][265] which were sacrificed to her alone.[265] The Greek word for "dove" was peristerá,[78][79] which may be derived from the Semitic phrase peraḥ Ištar, meaning "bird of Ishtar".[79] The myth of Aphrodite and Adonis is derived from the story of Inanna and Dumuzid.[248][249]

Classical scholar Charles Penglase has written that Athena, the Greek goddess of wisdom and defensive warfare, resembles Inanna's role as a "terrifying warrior goddess".[3] Others have noted that the birth of Athena from the head of her father Zeus could be derived from Inanna's descent into and return from the Underworld.[4][5]

The cult of Inanna may also have influenced the deities Ainina and Danina of the Caucasian Iberians mentioned by the medieval Georgian Chronicles.[270] Anthropologist Kevin Tuite argues that the Georgian goddess Dali was also influenced by Inanna,[271] noting that both Dali and Inanna were associated with the morning star,[272] both were characteristically depicted nude,[273] both were associated with gold jewelry,[273] both sexually preyed on mortal men,[274] both were associated with human and animal fertility,[275] and both had ambiguous natures as sexually attractive, but dangerous, women.[276] The Hindu goddess Durga may also have been influenced by Inanna.[6][7] Like Inanna, Durga was envisioned as a warrior goddess with a fierce temper who slew demons.[277][8] Both goddesses were portrayed riding on the backs of lions[8] and both were associated with the destruction of the wicked.[8] Like Inanna, Durga was also associated with sexuality.[278]

Traditional Mesopotamian religion began to gradually decline between the third and fifth centuries AD as ethnic Assyrians converted to Christianity.[279] Nonetheless, the cult of Ishtar and Tammuz managed to survive in parts of Upper Mesopotamia.[258] In the tenth century AD, an Arab traveler wrote that "All the Sabaeans of our time, those of Babylonia as well as those of Harran, lament and weep to this day over Tammuz at a festival which they, more particularly the women, hold in the month of the same name."[258] The cult of Ishtar still existed in Mardin as late as the eighteenth century.[279] Early Christians in the Middle East assimilated elements of Ishtar into the cult of the Virgin Mary.[280][8] The Syrian writers Jacob of Serugh and Romanos the Melodist both wrote laments in which the Virgin Mary describes her compassion for her son at the foot of the cross in deeply personal terms closely resembling Ishtar's laments over the death of Tammuz.[281]

Modern relevance[edit]

In his 1853 pamphlet The Two Babylons, as part of his argument that Roman Catholicism is actually Babylonian paganism in disguise, Alexander Hislop, a Protestant minister in the Free Church of Scotland, incorrectly argued that the modern English word Easter must be derived from Ishtar due to the phonetic similarity of the two words.[283] Modern scholars have unanimously rejected Hislop's arguments as erroneous and based on a flawed understanding of Babylonian religion.[284][285][286][287] Nonetheless, Hislop's book is still popular among some groups of evangelical Protestants[284][285] and the ideas promoted in it have become widely circulated, especially through the Internet, due to a number of popular Internet memes.[287]

Ishtar's first major appearance in modern literature was in Ishtar and Izdubar,[288] a book-length poem written in 1884 by Leonidas Le Cenci Hamilton, an American lawyer and businessman, loosely based on the recently-translated Epic of Gilgamesh.[288] Ishtar and Izdubar expanded the original roughly 3,000 lines of the Epic of Gilgamesh to roughly 6,000 lines of rhyming couplets grouped into forty-eight cantos.[282] Hamilton significantly altered most of the characters and introduced entirely new episodes not found in the original epic.[282] Significantly influenced by Edward FitzGerald's Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam and Edwin Arnold's The Light of Asia,[282] Hamilton's characters dress more like nineteenth-century Turks than ancient Babylonians.[289] In the poem, Izdubar (the earlier misreading for the name "Gilgamesh") falls in love with Ishtar,[290] but, then, "with hot and balmy breath, and trembling form aglow," she attempts to seduce him, leading Izdubar to reject her advances.[290] Several "columns" of the book are devoted to an account of Ishtar's descent into the Underworld.[289] At the conclusion of the book, Izdubar, now a god, is reconciled with Ishtar in Heaven.[291] In 1887, the composer Vincent d'Indy wrote Symphony Ishtar, variations symphonique, Op. 42, a symphony inspired by the Assyrian monuments in the British Museum.[292]

Inanna has become an important figure in modern feminist theory because she appears in the male-dominated Sumerian pantheon,[293] but is equally as powerful, if not more powerful than, the male deities she appears alongside.[293] Simone de Beauvoir, in her book The Second Sex (1949), argues that Inanna, along with other powerful female deities from antiquity, have been marginalized by modern culture in favor of male deities.[292] Tikva Frymer-Kensky has argued that Inanna was a "marginal figure" in Sumerian religion who embodies the "socially unacceptable" archetype of the "undomesticated, unattached woman".[292] Johanna Stuckey has argued against this idea, pointing out Inanna's centrality in Sumerian religion and her broad diversity of powers, neither of which seem to fit the idea that she was in any way regarded as "marginal".[292]

While classical deities such as Apollo and Aphrodite frequently appear in modern popular culture,[292] Mesopotamian deities have, by contrast, fallen into almost complete obscurity.[292] Inanna-Ishtar has somewhat resisted this tendency, but has not been immune to it.[292] She usually only appears in works with strong mythological input,[292] and most modern portrayals of Inanna-Ishtar have virtually nothing in common with the ancient goddess except for her name.[292] The 1963 splatter film Blood Feast concerns a serial killer who sacrifices his victims to Ishtar, who is incorrectly identified as an "Egyptian goddess".[294] Ishtar also gave her name to the 1987 box office bomb Ishtar, in which the character Shirra was loosely modeled on her.[293] According to Louise Pryke, the character Buffy Summers in Buffy the Vampire Slayer bears remarkably strong similarities to Ishtar,[295] but these may be coincidental.[296] Hercules: The Legendary Journeys, following the portrayal in Blood Feast, portrays Ishtar as a soul-eating Egyptian mummy.[294] One of the two highlands of the planet Venus is named "Ishtar Terra".[294] John Craton composed a full-length opera about Ishtar[292] and she has also been referenced in numerous rock and death metal songs.[297]

The Argentinian-born Jewish feminist artist Liliana Kleiner created an exhibition of paintings depicting her interpretations of Inanna's myths,[298] which was first displayed in Mexico in 2008.[298] The exhibition was later shown in Jerusalem in 2011 and in Berlin in 2015.[298] Inanna is one of the names on the Heritage Floor of The Dinner Party by American feminist artist Judy Chicago as a related woman to Ishtar, who has a seat at the table.[299] Inanna is worshipped as a form of the Goddess in modern Neopaganism and Wicca.[300] Her name occurs in the refrain of the "Burning Times Chant",[301] one of the most widely used Wiccan liturgies.[302] Inanna's Descent into the Underworld was the inspiration for the "Descent of the Goddess",[303][304] one of the most popular and most important myths in Gardnerian Wicca.[303][304]

Inanna is also an important figure in modern BDSM culture.[305] Author and historian Anne O. Nomis has cited the portrayal of Inanna in the myth of Inanna and Ebih as an early example of the dominatrix archetype,[306] characterizing her as a powerful female who forces gods and men into submission to her.[306] Scholar Paul Thomas has criticized the modern portrayal of Inanna, accusing it of anachronistically imposing modern gender conventions on the ancient Sumerian story, portraying Inanna as a wife and mother,[307] two roles the ancient Sumerians never ascribed to her,[307][1] while ignoring the more masculine elements of Inanna's cult, particularly her associations with warfare and violence.[307] Douglas E. Cowan has also criticized the portrayal of Inanna in modern Neopaganism, remarking that it "reduces [her] to little more than a patron goddess of parking lots and crawlspaces".[308]

Dates (approximate)[edit]

| Historical sources | ||

| Time | Period | Source |

| c. 5300–4100 BC | Ubaid period | |

| c. 4100–2900 BC | Uruk period | Uruk vase[31] |

| c. 2900–2334 BC | Early Dynastic period | |

| c. 2334–2218 BC | Akkadian Empire | writings by Enheduanna:[18][35] Nin-me-šara, "The Exaltation of Inanna" |

| c. 2218–2047 BC | Gutian Period | |

| c. 2047–1940 BC | Ur III Period | Enmerkar and the Lord of Aratta Gilgamesh, Enkidu, and the Netherworld |

See also[edit]

- Anat

- Asherah

- Holy Spirit

- Isis

- Mary, mother of Jesus

- Nana (Kushan goddess)

- Nanaya

- Sailor Venus, Sailor Moon character partially based on Inanna

- Sophia (Gnosticism)

- Star of Ishtar

- Venus

Notes[edit]

- ^ /ɪˈnɑːnə/; Sumerian: 𒀭𒈹 Dinanna, also 𒀭𒊩𒌆𒀭𒈾 Dnin-an-na[9][10]

- ^ /ˈɪʃtɑːr/; Dištar[9]

- ^ modern-day Warka, Biblical Erech

- ^ é-an-na means "sanctuary" ("house" + "Heaven" ["An"] + genitive)[42]

- ^ Dumuzid's Dream is attested in seventy-five known sources, fifty-five of which come from Nippur, nine from Ur, three probably from the region around Sippar, one each from Uruk, Kish, Shaduppum, and Susa.[211]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Black & Green 1992, p. 108.

- ^ a b c d e Leick 1998, p. 88.

- ^ a b c Penglase 1994, p. 235.

- ^ a b c Deacy 2008, pp. 20–21, 41.

- ^ a b c Penglase 1994, pp. 233–325.

- ^ a b c Parpola 1998, pp. 224–225, 260.

- ^ a b c Parpola 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g Baring & Cashford 1991.

- ^ a b Heffron 2016.

- ^ "Sumerian dictionary". oracc.iaas.upenn.edu.

- ^ Wolkstein & Kramer 1983, p. xviii.

- ^ a b Nemet-Nejat 1998, p. 182.

- ^ Wolkstein & Kramer 1983, p. xv.

- ^ Penglase 1994, pp. 42–43.

- ^ a b c d e f Kramer 1961, p. 101.

- ^ Collins 1994, pp. 114–115.

- ^ a b c Mark 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Leick 1998, p. 87.

- ^ a b c Wolkstein & Kramer 1983, pp. xviii, xv.

- ^ a b c d e Collins 1994, pp. 110–111.

- ^ a b Leick 1998, p. 86.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Harris 1991, pp. 261–278.

- ^ a b Wolkstein & Kramer 1983, pp. xiii–xix.

- ^ Rubio 1999, pp. 1–16.

- ^ a b c d Collins 1994, p. 110.

- ^ a b Leick 1998, p. 96.

- ^ Suter 2014, p. 51.

- ^ a b c Vanstiphout 1984, pp. 225–228.

- ^ a b Vanstiphout 1984, p. 228.

- ^ Vanstiphout 1984, pp. 228–229.

- ^ a b Suter 2014, p. 551.

- ^ a b Suter 2014, pp. 550–552.

- ^ Suter 2014, pp. 552–554.

- ^ a b c d Van der Mierop 2007, p. 55.

- ^ a b Collins 1994, p. 111.

- ^ Mark 2017.

- ^ Meador, Betty De Shong (2000). Inanna, Lady of Largest Heart: Poems of the Sumerian High Priestess Enheduanna. University of Texas Press. pp. 14–15. ISBN 978-0-292-75242-9.

- ^ Leick, Dr Gwendolyn (2002). A Dictionary of Ancient Near Eastern Mythology. Routledge. p. 86. ISBN 978-1-134-64103-1.

- ^ "Site officiel du musée du Louvre". cartelfr.louvre.fr.

- ^ Meador, Betty De Shong (2000). Inanna, Lady of Largest Heart: Poems of the Sumerian High Priestess Enheduanna. University of Texas Press. pp. 14–15. ISBN 978-0-292-75242-9.

- ^ a b c d Black & Green 1992, pp. 108–109.

- ^ Halloran 2009.

- ^ a b Black & Green 1992, p. 99.

- ^ a b Guirand 1968, p. 58.

- ^ a b Monaghan 2014, p. 39.

- ^ Leick 1994, pp. 157–158.

- ^ Leick 1994, p. 285.

- ^ Roscoe & Murray 1997, p. 65.

- ^ a b Roscoe & Murray 1997, pp. 65–66.

- ^ Leick 1994, pp. 158–163.

- ^ Roscoe & Murray 1997, p. 66.

- ^ a b c d e Kramer 1970.

- ^ a b c Nemet-Nejat 1998, p. 196.

- ^ a b Pryke 2017, p. 128.

- ^ Day 2004, pp. 15–17.

- ^ a b Marcovich 1996, p. 49.

- ^ Nemet-Nejat 1998, p. 193.

- ^ a b Assante 2003, pp. 14–47.

- ^ a b Day 2004, pp. 2–21.

- ^ a b Sweet 1994, pp. 85–104.

- ^ Pryke 2017, p. 61.

- ^ a b Ackerman 2006, pp. 116–117.

- ^ a b Ackerman 2006, p. 115.

- ^ a b Ackerman 2006, pp. 115–116.

- ^ a b Black & Green 1992, pp. 156, 169–170.

- ^ a b c Liungman 2004, p. 228.

- ^ a b c Black & Green 1992, p. 118.

- ^ a b c d Collins 1994, pp. 113–114.

- ^ Kleiner 2005, p. 49.

- ^ a b c Black & Green 1992, p. 170.

- ^ a b Black & Green 1992, pp. 169–170.

- ^ Nemet-Nejat 1998, pp. 193–194.

- ^ Gressman & Obermann 1928, p. 81.

- ^ Jacobsen 1976.

- ^ a b Black & Green 1992, p. 156.

- ^ Black & Green 1992, pp. 156–157.

- ^ Black & Green 1992, pp. 119.

- ^ a b c d e Lewis & Llewellyn-Jones 2018, p. 335.

- ^ a b c d e Botterweck & Ringgren 1990, p. 35.

- ^ Nemet-Nejat 1998, p. 203.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Cooley 2008, pp. 161–172.

- ^ Cooley 2008, pp. 163–164.

- ^ a b Foxvog 1993, p. 106.

- ^ Black & Green 1992, pp. 34–35.

- ^ Pumpelly, Raphael (1908), "Ancient Anau and the Oasis-World and General Discussion of Results", Explorations in Turkestan: Expedition of 1904: Prehistoric Civilizations of Anau: Origins, Growth and Influence of Environment, 73 (1): 48, retrieved 24 June 2018

- ^ Wolkstein & Kramer 1983, pp. 92, 193.

- ^ a b Penglase 1994, pp. 15–17.

- ^ a b Black & Green 1992, pp. 108–9.

- ^ Leick 1994, pp. 65–66.

- ^ Fiore 1965.

- ^ Gilgamesh, p. 86

- ^ Pryke 2017, p. 146.

- ^ Vanstiphout 1984, pp. 226–227.

- ^ Enheduanna pre 2250 BCE "A hymn to Inana (Inana C)". The Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature. 2003. lines 18–28. 4.07.3.

- ^ Vanstiphout 1984, p. 227.

- ^ Lung 2014.

- ^ Black & Green 1992, pp. 108, 182.

- ^ a b Wolkstein & Kramer 1983, pp. x–xi.

- ^ Pryke 2017, p. 36.

- ^ a b c Pryke 2017, pp. 36–37.

- ^ Black & Green 1992, p. 183.

- ^ a b c Pryke 2017, p. 94.

- ^ a b c Black & Green 1992, p. 77.

- ^ a b Pryke 2017, p. 108.

- ^ Wolkstein & Kramer 1983, p. ix-xi.

- ^ Jordan 2002, p. 137.

- ^ a b c d e f g Puhvel 1987, p. 25.

- ^ Wolkstein & Kramer 1983, pp. 71–84.

- ^ a b Leick 1998, p. 93.

- ^ Wolkstein & Kramer 1983, p. 89.

- ^ Black & Green 1992, p. 173.

- ^ a b Hallo 2010, p. 233.

- ^ Kramer 1963, pp. 172–174.

- ^ Kramer 1963, p. 174.

- ^ Kramer 1963, p. 182.

- ^ Kramer 1963, p. 183.

- ^ Kramer 1961, p. 30.

- ^ Wolkstein & Kramer 1983, p. 141.

- ^ Pryke 2017, pp. 153–154.

- ^ a b c d Kramer 1961, p. 33.

- ^ a b c d e f Mark 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f Fontenrose 1980, p. 172.

- ^ Kramer 1961, pp. 33–34.

- ^ Wolkstein & Kramer 1983, p. 140.

- ^ Kramer 1961, p. 34.

- ^ Wolkstein & Kramer 1983, p. 9.

- ^ a b c d e f g Leick 1998, p. 91.

- ^ Wolkstein & Kramer 1983, pp. 30–49.

- ^ a b Kramer 1961, pp. 102–103.

- ^ Kramer 1961, pp. 101–103.

- ^ Kramer 1961, pp. 32–33.

- ^ a b Leick 1998, p. 90.

- ^ a b c d Kramer 1961, p. 66.

- ^ a b Black & Green 1992, p. 130.

- ^ Kramer 1961, p. 65.

- ^ Kramer 1961, pp. 65–66.

- ^ Wolkstein & Kramer, pp. 13–14.

- ^ Wolkstein & Kramer 1983, p. 14.

- ^ Wolkstein & Kramer 1983, pp. 14–20.

- ^ a b Kramer 1961, pp. 66–67.

- ^ Wolkstein & Kramer 1983, p. 20.

- ^ Wolkstein & Kramer 1983, pp. 20–21.

- ^ Kramer 1961, p. 67.

- ^ Wolkstein & Kramer1983, p. 21.

- ^ Kramer 1961, pp. 67–68.

- ^ Wolkstein & Kramer 1983, pp. 20–24.

- ^ a b Kramer 1961, p. 68.

- ^ Wolkstein & Kramer 1961, pp. 20–24.

- ^ Wolkstein & Kramer 1983, pp. 24–25.

- ^ Wolkstein & Kramer 1983, pp. 26–27.

- ^ Green 2003, p. 74.

- ^ Wolkstein & Kramer 1983, p. 146-150.

- ^ Vanstiphout 2003, pp. 57–61.

- ^ a b Vanstiphout 2003, p. 49.

- ^ Vanstiphout 2003, pp. 57–63.

- ^ Vanstiphout 2003, pp. 61–63.

- ^ Vanstiphout 2003, pp. 63–87.

- ^ Vanstiphout 2003, p. 50.

- ^ Pryke 2017, pp. 162–173.

- ^ a b Pryke 2017, p. 165.

- ^ Attinger 1988, pp. 164–195.

- ^ a b c d Karahashi 2004, p. 111.

- ^ Kramer 1961, pp. 82–83.

- ^ a b Karahashi 2004, pp. 111–118.

- ^ Kramer 1961, p. 82.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Cooley 2008, p. 162.

- ^ a b Cooley 2008, p. 163.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Leick 1998, p. 89.

- ^ a b c d Fontenrose 1980, p. 165.

- ^ a b Pryke 2017, p. 166.

- ^ Black & Green 1992, p. 109.

- ^ a b c Kramer 1961, pp. 83–86.

- ^ a b c Wolkstein & Kramer 1983, pp. 127–135.

- ^ Dalley 1989, p. 154.

- ^ a b c Choksi 2014.

- ^ a b Kramer 1961, pp. 86–87.

- ^ a b c d Penglase 1994, p. 17.

- ^ Kramer 1961, p. 88.

- ^ Wolkstein & Kramer 1983, p. 56.

- ^ Wolkstein & Kramer 1983, p. 157.

- ^ a b c Kramer 1961, p. 90.

- ^ Wolkstein & Kramer 1983, pp. 54–55.

- ^ a b Wolkstein & Kramer 1983, p. 55.

- ^ Kramer 1961, p. 91.

- ^ Wolkstein & Kramer 1983, pp. 56–57.

- ^ Wolkstein 1983, p. 57.

- ^ Kilmer 1971, pp. 299–309.

- ^ Kramer 1961, p. 87.

- ^ a b Wolkstein & Kramer 1983, pp. 157–159.

- ^ Black, Jeremy; Cunningham, Graham; Flückiger-Hawker, Esther; Robson, Eleanor; Taylor, John; Zólyomi, Gábor. "Inana's descent to the netherworld". Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature. Oxford University. Retrieved 22 June 2017.

- ^ a b Kramer 1961, pp. 93–94.

- ^ Wolkstein & Kramer 1983, pp. 61–64.

- ^ Penglase 1994, pp. 17–18.

- ^ Wolkstein & Kramer 1983, pp. 61–62.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Penglase 1994, p. 18.

- ^ a b c d Kramer 1961, p. 94.

- ^ Wolkstein & Kramer 1983, pp. 62–63.

- ^ a b c Wolkstein & Kramer 1983, p. 64.

- ^ a b Wolkstein & Kramer 1983, pp. 65–66.

- ^ Wolkstein & Kramer 1983, p. 65.

- ^ Kramer 1961, pp. 94–95.

- ^ Wolkstein & Kramer 1983, pp. 67–68.

- ^ a b c Kramer 1961, p. 95.

- ^ a b c Wolkstein & Kramer 1983, pp. 68–69.

- ^ Kramer 1961, pp. 95–96.

- ^ Wolkstein & Kramer 1983, pp. 69–70.

- ^ a b c Kramer 1961, p. 96.

- ^ Wolkstein & Kramer 1983, pp. 70.

- ^ a b Wolkstein & Kramer 1983, pp. 70–71.

- ^ a b c Wolkstein & Kramer 1983, pp. 71–73.

- ^ a b Tinney 2018, p. 86.

- ^ Tinney 2018, pp. 85–86.

- ^ Wolkstein & Kramer 1983, pp. 74–84.

- ^ Wolkstein & Kramer 1983, pp. 85–87.

- ^ Wolkstein & Kramer 1983, pp. 87–89.

- ^ Wolkstein & Kramer 1983, pp. 88–89.

- ^ Kramer 1966, p. 31.

- ^ Wolkstein & Kramer 1983, pp. 85–89.

- ^ a b Dalley 1989, p. 155.

- ^ a b Dalley 1989, p. 156.

- ^ Dalley 1989, pp. 156–157.

- ^ Dalley 1989, p. 157-158.

- ^ a b c Dalley 1989, pp. 158–160.

- ^ Bertman 2003, p. 124.

- ^ Wolkstein & Kramer 1983, pp. 158–162.

- ^ Campbell 2008, pp. 88–90.

- ^ a b c d Hostetter 1991, p. 53.

- ^ a b Dalley 1989, pp. 81–82.

- ^ a b c d e f Dalley 1989, p. 80.

- ^ Gilgamesh, p. 86

- ^ Gilgamesh, p. 87

- ^ a b Fontenrose 1980, pp. 168–169.

- ^ a b c d e Dalley 1989, p. 82.

- ^ a b c d e Fontenrose 1980, p. 169.

- ^ Gilgamesh, p. 88

- ^ Dalley 1989, p. 82-83.

- ^ Dalley 1989, pp. 109–116.

- ^ Dalley 1989, pp. 109–111.

- ^ Dalley 1989, p. 113.

- ^ Dalley 1989, p. 114.

- ^ a b Dalley 1989, pp. 114–115.

- ^ Dalley, pp. 114–115.

- ^ Dalley 1989, p. 115.

- ^ a b Puhvel 1987, p. 27.

- ^ Güterbock et al. 2002, p. 29.

- ^ Black & Green 1992, p. 110.

- ^ a b c Westenholz 1997, pp. 33–49.

- ^ a b West 1997, p. 57.

- ^ a b Burkert 1985, p. 177.

- ^ a b Pryke 2017, p. 193.

- ^ Pryke 2017, pp. 193, 195.

- ^ Pryke 2017, pp. 193–195.

- ^ a b Breitenberger 2007, p. 10.

- ^ Smith 2002, p. 182.

- ^ a b Pryke 2017, p. 194.

- ^ Black & Green 1992, p. 73.

- ^ a b Pryke 2017, p. 195.

- ^ a b c d Warner 2016, p. 211.

- ^ a b Marcovich 1996, pp. 43–59.

- ^ a b c Cyrino 2010, pp. 49–52.

- ^ Breitenberger 2007, pp. 8–12.

- ^ a b c d Breitenberger 2007, p. 8.

- ^ a b c d Penglase 1994, p. 162.

- ^ a b Breitenberger 2007, pp. 10–11.

- ^ a b c d Penglase 1994, p. 163.

- ^ a b Cyrino 2010, pp. 51–52.

- ^ a b Budin 2010, pp. 85–86, 96, 100, 102–103, 112, 123, 125.

- ^ Graz 1984, p. 250.

- ^ a b Iossif & Lorber 2007, p. 77.

- ^ Tseretheli 1935, pp. 55–56.

- ^ Tuite 2004, pp. 16–18.

- ^ Tuite 2004, p. 16.

- ^ a b Tuite 2004, pp. 16–17.

- ^ Tuite 2004, p. 17.

- ^ Tuite 2004, pp. 17–18.

- ^ Tuite 2004, p. 18.

- ^ Parpola 1998, p. 225.

- ^ Parpola 1998, p. 260.

- ^ a b Parpola 2004, p. 17.

- ^ Warner 2016, pp. 210–212.

- ^ Warner 2016, p. 212.

- ^ a b c d Ziolkowski 2012, p. 21.

- ^ Hislop 1903, p. 103.

- ^ a b Grabbe 1997, p. 28.

- ^ a b Mcllhenny 2011, p. 60.

- ^ Brown 1976, p. 268.

- ^ a b D'Costa 2013.

- ^ a b Ziolkowski 2012, pp. 20–21.

- ^ a b Ziolkowski 2012, pp. 22–23.

- ^ a b Ziolkowski 2012, p. 22.

- ^ Ziolkowski 2012, p. 23.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Pryke 2017, p. 196.

- ^ a b c Pryke 2017, pp. 196–197.

- ^ a b c Pryke 2017, p. 203.

- ^ Pryke 2017, pp. 202–203.

- ^ Pryke 2017, p. 202.

- ^ Pryke 2017, p. 197.

- ^ a b c Kleiner 2016.

- ^ Chicago 2007.

- ^ Rountree 2017, p. 167.

- ^ Weston & Bennett 2013, p. 165.

- ^ Weston & Bennett, p. 165.

- ^ a b Buckland 2001, pp. 74–75.

- ^ a b Gallagher 2005, p. 358.

- ^ Nomis 2013, pp. 59–60.

- ^ a b Nomis 2013, p. 53.

- ^ a b c Thomas 2007, p. 1.

- ^ Cowan 2005, p. 49.

Bibliography[edit]

- Ackerman, Susan (2006) [1989], Day, Peggy Lynne (ed.), Gender and Difference in Ancient Israel, Minneapolis, Minnesota: Fortress Press, ISBN 978-0-8006-2393-7CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Assante, Julia (2003), "From Whores to Hierodules: The Historiographic Invention of Mesopotamian Female Sex Professionals", in Donahue, A. A.; Fullerton, Mark D. (eds.), Ancient Art and Its Historiography, Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press, pp. 13–47CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Attinger, Pascal (1988), "Inana et Ebih", Zeitschrift für Assyriologie, 3, pp. 164–195

- Baring, Anne; Cashford, Jules (1991), The Myth of the Goddess: Evolution of an Image, London, England: Penguin Books, ISBN 978-0140192926CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bertman, Stephen (2003), Handbook to Life in Ancient Mesopotamia, Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-019-518364-1CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Black, Jeremy; Green, Anthony (1992), Gods, Demons and Symbols of Ancient Mesopotamia: An Illustrated Dictionary, The British Museum Press, ISBN 978-0-7141-1705-8CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Botterweck, G. Johannes; Ringgren, Helmer (1990), Theological Dictionary of the Old Testament, VI, Grand Rapids, Michigan: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., ISBN 978-0-8028-2330-4CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Breitenberger, Barbara (2007), Aphrodite and Eros: The Development of Greek Erotic Mythology, New York City, New York and London, England, ISBN 978-0-415-96823-2CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Brown, Peter Lancaster (1976), Megaliths, Myths and Men: An Introduction to Astro-Archaeology, New York City, New York: Dover Publications, ISBN 9780800851873CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Buckland, Raymond (2001), Wicca for Life: The Way of the Craft -- From Birth to Summerland, New York City, New York: Kensington Publishing Corporation, ISBN 978-0-8065-2455-9CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Budin, Stephanie L. (2010), "Aphrodite Enoplion", in Smith, Amy C.; Pickup, Sadie (eds.), Brill's Companion to Aphrodite, Brill's Companions in Classical Studies, Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill Publishers, pp. 85–86, 96, 100, 102–103, 112, 123, 125, ISBN 9789047444503CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Burkert, Walter (1985), Greek Religion, Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, ISBN 978-0-674-36281-9CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Campbell, Joseph (2008), The Hero with a Thousand Faces, Novato, California: New World Library, pp. 88–90

- Chicago, Judy (2007), The Dinner Party: From Creation to Preservation, London, England: Merrell, ISBN 978-1-85894-370-1

- Choksi, M. (2014), "Ancient Mesopotamian Beliefs in the Afterlife", Ancient History Encyclopedia, ancient.eu

- Collins, Paul (1994), "The Sumerian Goddess Inanna (3400-2200 BC)", Papers of from the Institute of Archaeology, 5, UCL

- Cooley, Jeffrey L. (2008), "Inana and Šukaletuda: A Sumerian Astral Myth", KASKAL, 5: 161–172, ISSN 1971-8608

- Cowan, Douglas E. (2005), Cyberhenge: Modern Pagans on the Internet, New York: Routledge, ISBN 978-0-415-96910-9

- Cyrino, Monica S. (2010), Aphrodite, Gods and Heroes of the Ancient World, New York City, New York and London, England: Routledge, ISBN 978-0-415-77523-6CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dalley, Stephanie (1989), Myths from Mesopotamia: Creation, the Flood, Gilgamesh, and Others, Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-283589-5CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Day, John (2004), "Does the Old Testament Refer to Sacred Prostitution and Did It Actual Exist in Ancient Israel?", in McCarthy, Carmel; Healey, John F. (eds.), Biblical and Near Eastern Essays: Studies in Honour of Kevin J. Cathcart, Cromwell Press, pp. 2–21, ISBN 978-0-8264-6690-7CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- D'Costa, Krystal (31 March 2013), "Beyond Ishtar: The Tradition of Eggs at Easter: Don't believe every meme you encounter.", Scientific American, Nature America, Inc.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Enheduanna. "The Exaltation of Inanna (Inanna B): Translation". The Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature. 2001.

- Fiore, Simon (1965), Voices From the Clay: The Development of Assyro-Babylonian Literature, Norman, University of Oklahoma Press

- Fontenrose, Joseph Eddy (1980) [1959], Python: A Study of Delphic Myth and Its Origins, Berkeley, California, Los Angeles, California, and London, England: The University of California Press, ISBN 978-0-520-04106-6CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Foxvog, D. (1993), "Astral Dumuzi", in Hallo, William W.; Cohen, Mark E.; Snell, Daniel C.; et al. (eds.), The Tablet and the scroll: Near Eastern studies in honor of William W. Hallo (2nd ed.), CDL Press, p. 106, ISBN 978-0962001390

- George, Andrew, ed. (1999), The Epic of Gilgamesh: The Babylonian Epic Poem and Other Texts in Akkadian and Sumerian, Penguin, ISBN 0-14-044919-1

- Gallagher, Ann-Marie (2005), The Wicca Bible: The Definitive Guide to Magic and the Craft, New York City, New York: Sterling Publishing Co., Inc., ISBN 978-1-4027-3008-5CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Grabbe, Lester L. (1997), Can a "History of Israel" Be Written?, The Library of Hebrew Bible/Old Testament Studies, 245, Sheffield, England: Sheffield Academic Press, ISBN 978-0567043207CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Graz, F. (1984), Eck, W. (ed.), "Women, War, and Warlike Divinities", Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik, Bonn, Germany: Dr. Rudolf Habelt GmbH, 55 (55): 245–254, JSTOR 20184039CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Green, Alberto R. W. (2003). The Storm-God in the Ancient Near East. Winona Lake, Indiana: Eisenbrauns. ISBN 9781575060699.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Guirand, Felix (1968), "Assyro-Babylonian Mythology", New Larousse Encyclopedia of Mythology, translated by Aldington; Ames, London, England: Hamlyn, pp. 49–72CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hallo, William W. (2010), The World's Oldest Literature: Studies in Sumerian Belles-Lettres, Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill, ISBN 978-90-04-17-381-1CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Harris, Rivkah (February 1991), "Inanna-Ishtar as Paradox and a Coincidence of Opposites", History of Religions, 30 (3): 261–278, doi:10.1086/463228, JSTOR 1062957

- Heffron, Yağmur (2016), "Inana/Ištar (goddess)", Ancient Mesopotamian Gods and Goddesses, University of Pennsylvania Museum

- Hislop, Alexander (1903) [1853], The Two Babylons: The Papal Worship Proved to Be the Worship of Nimrod and His Wife (Third ed.), S.W. PartridgeCS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hostetter, Clyde (1991), Star Trek to Hawa-i'i, San Luis Obispo, California: Diamond Press, p. 53

- Jacobsen, Thorkild (1976), The Treasures of Darkness: A History of Mesopotamian Religion, Yale University Press, ISBN 978-0-300-02291-9CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jordan, Michael (2002), Encyclopedia of Gods, London, England: Kyle Cathie Limited, ISBN 978-1856261319CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)