Moirai

| Moirai | |

|---|---|

Goddesses of Fate | |

| |

| Symbol | white robes, thread, dove, spindle, scissors |

| Personal information | |

| Parents | Chronos and Ananke Ouranos Nyx Zeus and Themis |

| Siblings | Horae |

In ancient Greek religion and mythology, the Moirai (/ˈmɔɪraɪ, -riː/;[1][2] Ancient Greek: Μοῖραι, "lots, destinies, apportioners"), often known in English as the Fates (Latin: Fata), Moirae or Mœræ (obsolete), were the white-robed incarnations of destiny; their Roman equivalent was the Parcae (euphemistically the "sparing ones"), and there are other equivalents in cultures that descend from the Proto-Indo-European culture. Their number became fixed at three: Clotho ("spinner"), Lachesis ("allotter") and Atropos ("the unturnable", a metaphor for death).

They controlled the mother thread of life of every mortal from birth to death. They were independent, at the helm of necessity, directed fate, and watched that the fate assigned to every being by eternal laws might take its course without obstruction. Both gods and men had to submit to them, although Zeus's relationship with them is a matter of debate: some sources say he can command them (as Zeus Moiragetes "leader of the Fates"), while others suggest he was also bound to the Moirai's dictates.[3]

In the Homeric poems Moira or Aisa are related to the limit and end of life, and Zeus appears as the guider of destiny. In the Theogony of Hesiod, the three Moirai are personified, daughters of Nyx and are acting over the gods.[4] Later they are daughters of Zeus and Themis, who was the embodiment of divine order and law. In Plato's Republic the Three Fates are daughters of Ananke (necessity).[5]

It seems that Moira is related with Tekmor ("proof, ordinance") and with Ananke ("destiny, necessity"), who were primordial goddesses in mythical cosmogonies. The ancient Greek writers might call this power Moira or Ananke, and even the gods could not alter what was ordained:

To the Moirai (Moirae, Fates) the might of Zeus must bow; and by the Immortals' purpose all these things had come to pass, or by the Moirai's ordinance.[6][7]

The concept of a universal principle of natural order and balance has been compared to similar concepts in other cultures like the Vedic Ṛta, the Avestan Asha (Arta) and the Egyptian Maat.

In earliest Greek philosophy, the cosmogony of Anaximander is based on these mythical beliefs. The goddess Dike ("justice, divine retribution"), keeps the order and sets a limit to any actions.[8]

The feminine name Moira is derived from it.

Etymology[edit]

The ancient Greek word moira (μοῖρα) means a portion or lot of the whole, and is related to meros, "part, lot" and moros, "fate, doom",[9] Latin meritum, "reward", English merit, derived from the PIE root *(s)mer, "to allot, assign".[10]

Moira may mean portion or share in the distribution of booty (ίση μοῖρα, ísē moîra, "equal booty"),[11] portion in life, lot, destiny, (μοῖραv ἔθηκαν ἀθάνατοι, moîran éthēken athánatoi, "the immortals fixed the destiny"),[12] death (μοῖρα θανάτοιο, moîra thanátoio, "destiny of death"), portion of the distributed land.[13] The word is also used for something which is meet and right (κατὰ μοῖραν, kata moîran, "according to fate, in order, rightly").[14]

It seems that originally the word moira did not indicate destiny but included ascertainment or proof, a non-abstract certainty. The word daemon, which was an agent related to unexpected events, came to be similar to the word moira.[15] This agent or cause against human control might be also called tyche (chance, fate): "You mistress moira, and tyche, and my daemon."[16]

The word nomos, "law", may have meant originally a portion or lot, as in the verb nemein, "to distribute", and thus "natural lot" came to mean "natural law".[17] The word dike, "justice", conveyed the notion that someone should stay within his own specified boundaries, respecting the ones of his neighbour. If someone broke his boundaries, thus getting more than his ordained part, then he would be punished by law. By extension, moira was one's portion or part in destiny which consisted of good and bad moments as was predetermined by the Moirai (Fates), and it was impossible for anyone to get more than his ordained part. In modern Greek the word came to mean "destiny" (μοίρα or ειμαρμένη).

Kismet, the predetermined course of events in the Muslim traditions, seems to have a similar etymology and function: Arabic qismat "lot" qasama, "to divide, allot" developed to mean Fate or destiny. As a loanword, qesmat 'fate' appears in Persian, whence in Urdu language, and eventually in English Kismet.

The three Moirai[edit]

When they were three,[18] the Moirai were:

- Clotho (/ˈkloʊθoʊ/, Greek Κλωθώ, [klɔːtʰɔ̌ː], "spinner") spun the thread of life from her distaff onto her spindle. Her Roman equivalent was Nona ("the ninth"), who was originally a goddess called upon in the ninth month of pregnancy.

- Lachesis (/ˈlækɪsɪs/, Greek Λάχεσις, [lákʰesis], "allotter" or drawer of lots) measured the thread of life allotted to each person with her measuring rod. Her Roman equivalent was Decima ("the Tenth").

- Atropos (/ˈætrəpɒs/, Greek Ἄτροπος, [átropos], "inexorable" or "inevitable", literally "unturning",[19] sometimes called Aisa) was the cutter of the thread of life. She chose the manner of each person's death; and when their time was come, she cut their life-thread with "her abhorred shears".[20] Her Roman equivalent was Morta ("the dead one").

In the Republic of Plato, the three Moirai sing in unison with the music of the Seirenes. Lachesis sings the things that were, Clotho the things that are, and Atropos the things that are to be.[21] Pindar in his Hymn to the Fates, holds them in high honour. He calls them to send their sisters, the Hours Eunomia ("lawfulness"), Dike ("right"), and Eirene ("peace"), to stop the internal civil strife:

Listen Fates, who sit nearest of gods to the throne of Zeus,

and weave with shuttles of adamant,

inescapable devices for councels of every kind beyond counting,

Aisa, Clotho and Lachesis,

fine-armed daughters of Night,

hearken to our prayers, all-terrible goddesses,

of sky and earth.

Send us rose-bosomed Lawfulness,

and her sisters on glittering thrones,

Right and crowned Peace, and make this city forget the misfortunes which lie heavily on her heart.[22]

Origins[edit]

In ancient times caves were used for burial purposes in eastern Mediterranean, along with underground shrines or temples. The priests and the priestesses had considerable influence upon the world of the living. Births are recorded in such shrines, and the Greek legend of conception and birth in the tomb—as in the story of Danae—is based on the ancient belief that the dead know the future. Such caves were the caves of Ida and Dikte mountains in Crete, where myth situates the birth of Zeus and other gods, and the cave of Eileithyia near Knossos.[23] The relative Minoan goddesses were named Diktynna (later identified with Artemis), who was a mountain nymph of hunting, and Eileithyia who was the goddess of childbirth.[24]

It seems that in Pre-Greek religion Aisa was a daemon. In Mycenaean religion Aisa or Moira was originally a living power related with the limit and end of life. At the moment of birth she spins the destiny, because birth ordains death.[25] Later Aisa is not alone, but she is accompanied by the "Spinners", who are the personifications of Fate.[26] The act of spinning is also associated with the gods, who at birth and at marriage do not spin the thread of life, but individual events like destruction, return or good fortune. Everything which has been spun must be wound on the spindle, and this was considered a cloth, like a net or loop which captured man.[27]

Invisible bonds and knots could be controlled from a loom, and twining was a magic art used by the magicians to harm a person and control his individual fate.[28] Similar ideas appear in Norse mythology,[29] and in Greek folklore. The appearance of the gods and the Moirai may be related to the fairy tale motif, which is common in many Indo-European sagas and also in Greek folklore. The fairies appear beside the cradle of the newborn child and bring gifts to him.[30]

Temple attendants may be considered representations of the Moirai, who belonged to the underworld, but secretly guided the lives of those in the upperworld. Their power could be sustained by witchcraft and oracles.[23] In Greek mythology the Moirai at birth are accompanied by Eileithyia. At the birth of Hercules they use together a magic art, to free the newborn from any "bonds" and "knots".[28]

The Homeric Moira[edit]

Much of the Mycenaean religion survived into classical Greece, but it is not known to what extent classical religious belief is Mycenaean, nor how much is a product of the Greek Dark Ages or later. Moses I. Finley detected only few authentic Mycenaean beliefs in the 8th-century Homeric world.[31] The religion which later the Greeks considered Hellenic embodies a paradox. Though the world is dominated by a divine power bestowed in different ways on men, nothing but "darkness" lay ahead. Life was frail and unsubstantial, and man was like "a shadow in a dream".[32]

In the Homeric poems the words moira, aisa, moros mean "portion, part". Originally they did not indicate a power which led destiny, and must be considered to include the "ascertainment" or "proof". By extension Moira is the portion in glory, happiness, mishappenings, death (μοίρα θανάτοιο "destiny of death") which are unexpected events. The unexpected events were usually attributed to daemons, who appeared in special occurrences. In that regard Moira was later considered an agent; Martin P. Nilsson associated these daemons to a supposed "Pre-Greek religion".[33]

People believed that their portion in destiny was something similar with their portion in booty, which was distributed according to their descent, and traditional rules. It was possible to get more than their ordained portion (moira), but they had to face severe consequences because their action was "over moira" (υπέρ μοίραν "over the portion"). It may be considered that they "broke the order". The most certain order in human lives is that every human should die, and this was determined by Aisa or Moira at the moment of birth.[25] The Mycenaeans believed that what comes should come (fatalism), and this was considered rightly offered (according to fate: in order). If someone died in battle, he would exist like a shadow in the gloomy space of the underworld.[33]

The kingdom of Moira is the kingdom of the limit and the end. In a passage in Iliad, Apollo tries three times to stop Patroclus in front of the walls of Troy, warning him that it is "over his portion" to sack the city. Aisa (moira) seems to set a limit on the most vigorous men's actions.[34]

Moira is a power acting in parallel with the gods, and even they could not change the destiny which was predetermined. In the Iliad, Zeus knows that his dearest Sarpedon will be killed by Patroclus, but he cannot save him.[35] In the famous scene of Kerostasia, Zeus appears as the guider of destiny. Using a pair of scales he decides that Hector must die, according to his aisa (destiny).[36] His decision seems to be independent from his will, and is not related with any "moral purpose". His attitude is explained by Achilleus to Priam, in a parable of two jars at the door of Zeus, one of which contains good things, and the other evil. Zeus gives a mixture to some men, to others only evil and such are driven by hunger over the earth. This was the old "heroic outlook".[37]

The personification of Moira appears in the newer parts of the epos. In the Odyssey, she is accompanied by the "Spinners", the personifications of Fate, who do not have separate names.[26] Moira seems to spin the predetermined course of events. Agamemnon claims that he is not responsible for his arrogance. He took the prize of Achilleus, because Zeus and Moira predetermined his decision.[38] In the last section of the Iliad, Moira is the "mighty fate" (μοίρα κραταιά moíra krataiá) who leads destiny and the course of events. Thetis the mother of Achilleus warns him that he will not live long because mighty fate stands hard by him, therefore he must give to Priam the corpse of Hector.[39] At Hector's birth mighty fate predetermined that his corpse would be devoured by dogs after his death, and Hecabe is crying desperately asking for revenge.[40]

Mythical cosmogonies[edit]

The three Moirai are daughters of the primeval goddess Nyx ("night"), and sisters of Keres ("the black fates"), Thanatos ("death") and Nemesis ("retribution").[4] Later they are daughters of Zeus and the Titaness Themis ("the Institutor"),[41] who was the embodiment of divine order and law.[42][43] and sisters of Eunomia ("lawfulness, order"), Dike ("justice"), and Eirene ("peace").[41]

Hesiod introduces a moral purpose which is absent in the Homeric poems. The Moirai represent a power to which even the gods have to conform. They give men at birth both evil and good moments, and they punish not only men but also gods for their sins.[4]

In the cosmogony of Alcman (7th century BC), first came Thetis ("disposer, creation"), and then simultaneously Poros ("path") and Tekmor ("end post, ordinance").[44][45] Poros is related with the beginning of all things, and Tekmor is related with the end of all things.[46]

Later in the Orphic cosmogony, first came Thesis ("disposer"), whose ineffable nature is unexpressed. Ananke ("necessity") is the primeval goddess of inevitability who is entwined with the time-god Chronos, at the very beginning of time. They represented the cosmic forces of Fate and Time, and they were called sometimes to control the fates of the gods. The three Moirai are daughters of Ananke.[47]

Mythology[edit]

The Moirai were supposed to appear three nights after a child's birth to determine the course of its life, as in the story of Meleager and the firebrand taken from the hearth and preserved by his mother to extend his life.[48] Bruce Karl Braswell from readings in the lexicon of Hesychius, associates the appearance of the Moirai at the family hearth on the seventh day with the ancient Greek custom of waiting seven days after birth to decide whether to accept the infant into the Gens and to give it a name, cemented with a ritual at the hearth.[49] At Sparta the temple to the Moirai stood near the communal hearth of the polis, as Pausanias observed.[50]

As goddesses of birth who even prophesied the fate of the newly born, Eileithyia, the ancient Minoan goddess of childbirth and divine midwifery, was their companion. Pausanias mentions an ancient role of Eileythia as "the clever spinner", relating her with destiny too.[51] Their appearance indicate the Greek desire for health which was connected with the Greek cult of the body that was essentially a religious activity.[52]

The Moirai assigned to the terrible chthonic goddesses Erinyes who inflicted the punishment for evil deeds their proper functions, and with them directed fate according to necessity. As goddesses of death they appeared together with the daemons of death Keres and the infernal Erinyes.[53]

In earlier times they were represented as only a few—perhaps only one—individual goddess. Homer's Iliad (xxiv.209) speaks generally of the Moira, who spins the thread of life for men at their birth; she is Moira Krataia "powerful Moira" (xvi.334) or there are several Moirai (xxiv.49). In the Odyssey (vii.197) there is a reference to the Klôthes, or Spinners. At Delphi, only the Fates of Birth and Death were revered.[54] In Athens, Aphrodite, who had an earlier, pre-Olympic existence, was called Aphrodite Urania the "eldest of the Fates" according to Pausanias (x.24.4).

Some Greek mythographers went so far as to claim that the Moirai were the daughters of Zeus—paired with Themis ("fundament"), as Hesiod had it in one passage.[55] In the older myths they are daughters of primeval beings like Nyx ("night") in Theogony, or Ananke ("necessity") in Orphic cosmogony. Whether or not providing a father even for the Moirai was a symptom of how far Greek mythographers were willing to go, in order to modify the old myths to suit the patrilineal Olympic order,[56] the claim of a paternity was certainly not acceptable to Aeschylus, Herodotus, or Plato.

Despite their forbidding reputation, the Moirai could be placated as goddesses. Brides in Athens offered them locks of hair, and women swore by them. They may have originated as birth goddesses and only later acquired their reputation as the agents of destiny.

According to the mythographer Apollodorus, in the Gigantomachy, the war between the Giants and Olympians, the Moirai killed the Giants Agrios and Thoon with their bronze clubs.[57]

Zeus and the Moirai[edit]

In the Homeric poems Moira, who is almost always one, is acting independently from the gods. Only Zeus, the chief sky-deity of the Mycenaeans is close to Moira, and in a passage he is the being of this power.[33] Using a weighing scale (balance) Zeus weighs Hector's "lot of death" (Ker) against the one of Achilleus. Hector's lot weighs down, and he dies according to Fate. Zeus appears as the guider of destiny, who gives everyone the right portion.[58][59]

In a Mycenaean vase, Zeus holds a weighing scale (balance) in front of two warriors, indicating that he is measuring their destiny before the battle. The belief (fatalism) was that if they die in battle, they must die, and this was rightly offered (according to fate).[60]

In Theogony, the three Moirai are daughters of the primeval goddess, Nyx ("Night"),[61] representing a power acting over the gods.[4] Later they are daughters of Zeus who gives them the greatest honour, and Themis, the ancient goddess of law and divine order.[42][43]

Even the gods feared the Moirai or Fates, which according to Herodotus a god could not escape.[62] The Pythian priestess at Delphi once admitted that Zeus was also subject to their power, though no recorded classical writing clarifies to what exact extent the lives of immortals were affected by the whims of the Fates. It is to be expected that the relationship of Zeus and the Moirai was not immutable over the centuries. In either case in antiquity we can see a feeling towards a notion of an order to which even the gods have to conform. Simonides names this power Ananke (necessity) (the mother of the Moirai in Orphic cosmogony) and says that even the gods don't fight against it.[63] Aeschylus combines Fate and necessity in a scheme, and claims that even Zeus cannot alter which is ordained.[7]

A supposed epithet Zeus Moiragetes, meaning "Zeus Leader of the Moirai" was inferred by Pausanias from an inscription he saw in the 2nd century AD at Olympia: "As you go to the starting-point for the chariot-race there is an altar with an inscription to the Bringer of Fate.[64] This is plainly a surname of Zeus, who knows the affairs of men, all that the Fates give them, and all that is not destined for them."[65] At the Temple of Zeus at Megara, Pausanias inferred from the relief sculptures he saw "Above the head of Zeus are the Horai and Moirai, and all may see that he is the only god obeyed by Moira." Pausanias' inferred assertion is unsupported in cult practice, though he noted a sanctuary of the Moirai there at Olympia (v.15.4), and also at Corinth (ii.4.7) and Sparta (iii.11.8), and adjoining the sanctuary of Themis outside a city gate of Thebes.[66]

Cult and temples[edit]

The fates had at least three known temples, in Ancient Corinth, Sparta and Thebes. At least the temple of Corinth contained statues of them:

- "[On the Akropolis (Acropolis) of Korinthos (Corinth) :] The temple of the Moirai (Moirae, Fates) and that of Demeter and Kore (Core) [Persephone] have images that are not exposed to view."[67]

The temple in Thebes was explicitly imageless:

- "Along the road from the Neistan gate [at Thebes in Boiotia (Boeotia)] are three sanctuaries. There is a sanctuary of Themis, with an image of white marble; adjoining it is a sanctuary of the Moirai (Moirae, Fates), while the third is of Agoraios (Agoreus, of the Market) Zeus. Zeus is made of stone; the Moirai (Moirae, Fates) have no images."[68]

The temple in Sparta was situated next to the grave of Orestes.[69]

Aside from actual temples, there was also altars to the Moirai. Among them was notably the altar in Olympia near the altar of Zeus Moiragetes,[70] a connection to Zeus which was also repeated in the images of the Moirai in the temple of Despoine in Arkadia[71] as well as in Delphi, where they were depicted with Zeus Moiragetes (Guide of Fate) as well as with Apollon Moiragetes (Guide of Fate).[72] On Korkyra, the shrine of Apollo, which according to legend was founded by Medea was also a place where offerings were made to the Moirai and the nymphs.[73] The worship of the Moirai are described by Pausanias for their altar near Sicyon:

- "On the direct road from Sikyon (Sicyon) to Phlios (Phlius) ... At a distance along it, in my opinion, of twenty stades, to the left on the other side of the Asopos [river], is a grove of holm oaks and a temple of the goddesses named by the Athenians the Semnai (August), and by the Sikyonians the Eumenides (Kindly Ones). On one day in each year they celebrate a festival to them and offer sheep big with young as a burnt offering, and they are accustomed to use a libation of honey and water, and flowers instead of garlands. They practise similar rites at the altar of the Moirai (Moirae, Fates); it is in an open space in the grove."[74]

Cross-cultural parallels[edit]

Europe[edit]

In Hurrian mythology the three goddesses of fate, the Hutena, was believed to dispense good and evil, life and death to humans.

In Roman mythology the three Moirai are the Parcae or Fata, plural of "fatum" meaning prophetic declaration, oracle, or destiny. The English words fate (native wyrd) and fairy ("magic, enchantment"), are both derived from "fata", "fatum".[75]

In Norse mythology the Norns are female beings who rule the destiny of gods and men, twining the thread of life. They set up the laws and decided on the lives of the children of men.[76] Their names were Urðr, related with Old English wyrd, modern weird ("fate, destiny, luck"), Verðandi, and Skuld, and it has often been inferred that they ruled over the past, present and future respectively, based on the sequence and partly the etymology of the names, of which the first two (literally 'Fate' and 'Becoming') are derived from the past and present stems of the verb verða, "to be", respectively,[77] and the name of the third one means "debt" or "guilt", originally "that which must happen".[78]

In younger legendary sagas, the Norns appear to have been synonymous with witches (völvas), and they arrive at the birth of the hero to shape his destiny. It seems that originally all of them were Disir, ghosts or deities associated with destruction and destiny. The notion that they were three may be due to a late influence from Greek and Roman mythology.[79] The same applies to their (disputed) association with the past, present and future.

The Valkyries (choosers of the slain), were originally daemons of death. They were female figures who decided who will die in battle, and brought their chosen to the afterlife hall of the slain. They were also related with spinning, and one of them was named Skuld ("debt, guilt").[80] They may be related to Keres, the daemons of death in Greek mythology, who accompanied the dead to the entrance of Hades. In the scene of Kerostasia, Keres are the "lots of death", and in some cases Ker ("destruction") has the same meaning, with Moira interpreted as "destiny of death" (moira thanatoio: μοίρα θανάτοιο).[4][81]

The Celtic Matres and Matrones, female deities almost entirely in a group of three, have been proposed as connected to the Norns and the Valkyries.[82]

In Anglo-Saxon culture Wyrd (Weird) is a concept corresponding to fate or personal destiny (literally: "what befalls one"). Its Norse cognate is Urðr, and both names are derived from the PIE root wert, "to turn, wind",[83] related with "spindle, distaff".[84] In Old English literature Wyrd goes ever as she shall, and remains wholly inevitable.[85][86]

In Dante's Divine Comedy, the Fates are mentioned in both Inferno (XXXIII.126) and Purgatorio (XXI.25-27, XXV.79-81) by their Greek names and their traditional role in measuring out and determining the length of human life is assumed by the narrator.

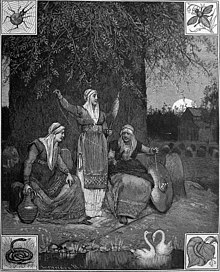

In Shakespeare's Macbeth, the Weird sisters (or Three Witches), are prophetesses, who are deeply entrenched in both worlds of reality and supernatural. Their creation was influenced by British folklore, witchcraft, and the legends of the Norns and the Moirai.[87] Hecate, the chthonic Greek goddess associated with magic, witchcraft, necromancy, and three-way crossroads,[88] appears as the master of the "Three witches". In ancient Greek religion, Hecate as goddess of childbirth is identified with Artemis,[89] who was the leader (ηγεμόνη: hegemone ) of the nymphs.[90]

In Lithuanian mythology Laima is the personification of destiny, and her most important duty was to prophecy how the life of a newborn will take place. She may be related to the Hindu goddess Laksmi, who was the personification of wealth and prosperity, and associated with good fortune.[91][92] In Latvian mythology, Laima and her sisters were a trinity of fate deities.[93]

The Moirai were usually described as cold, remorseless and unfeeling, and depicted as old crones or hags. The independent spinster has always inspired fear rather than matrimony: "this sinister connotation we inherit from the spinning goddess," write Ruck and Staples (Ruck and Staples 1994). See Weaving (mythology).

The Three Fates continue as common characters in modern literature.

Outside of Europe[edit]

The notion of a universal principle of natural order has been compared to similar ideas in other cultures, such as aša (Asha) in Avestan religion, Rta in Vedic religion, and Maat in ancient Egyptian religion.[94]

In the Avestan religion and Zoroastrianism, aša, is commonly summarized in accord with its contextual implications of "truth", "right(eousness)", "order". Aša and its Vedic equivalent, Rta, are both derived from a PIE root meaning "properly joined, right, true". The word is the proper name of the divinity Asha, the personification of "Truth" and "Righteousness". Aša corresponds to an objective, material reality which embraces all of existence.[95] This cosmic force is imbued also with morality, as verbal Truth, and Righteousness, action conforming with the moral order.[96] In the literature of the Mandeans, an angelic being has the responsibility of weighing the souls of the deceased to determine their worthiness, using a set of scales.[97]

In the Vedic religion, Rta is an ontological principle of natural order which regulates and coordinates the operation of the universe. The term is now interpreted abstractly as "cosmic order", or simply as "truth",[98] although it was never abstract at the time.[99] It seems that this idea originally arose in the Indo-Aryan period, from a consideration (so denoted to indicate the original meaning of communing with the star beings) of the qualities of nature which either remain constant or which occur on a regular basis.[100]

The individuals fulfill their true natures when they follow the path set for them by the ordinances of Rta, acting according to the Dharma, which is related to social and moral spheres.[101] The god of the waters Varuna was probably originally conceived as the personalized aspect of the otherwise impersonal Ṛta.[102] The gods are never portrayed as having command over Ṛta, but instead they remain subject to it like all created beings.[101]

In Egyptian religion, maat was the ancient Egyptian concept of truth, balance, order, law, morality, and justice. The word is the proper name of the divinity Maat, who was the goddess of harmony, justice, and truth represented as a young woman. It was considered that she set the order of the universe from chaos at the moment of creation.[103] Maat was the norm and basic values that formed the backdrop for the application of justice that had to be carried out in the spirit of truth and fairness.[104]

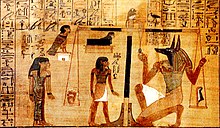

In Egyptian mythology, Maat dealt with the weighing of souls that took place in the underworld. Her feather was the measure that determined whether the souls (considered to reside in the heart) of the departed would reach the paradise of afterlife successfully. In the famous scene of the Egyptian Book of the Dead, Anubis, using a scale, weighs the sins of a man's heart against the feather of truth, which represents maat. If man's heart weighs down, then he is devoured by a monster.[105]

Astronomical objects[edit]

The asteroids (97) Klotho, (120) Lachesis, and (273) Atropos are named for the Three Fates.

See also[edit]

- Ananke

- Asha

- Deities and fairies of fate in Slavic mythology

- Istustaya and Papaya

- Kallone

- Enchanted Moura

- Laima

- Matrones

- Norns

- Parcae

- Rta

- Tekmor

- Three Witches

- Trimurti/Tridevi

Notes[edit]

- ^ Moirai in Oxford Living Dictionary

- ^ Moirai in Collins English Dictionary

- ^ "Theoi project: Moirae and the Throne of Zeus". Theoi.com. Retrieved 2013-01-24.

- ^ a b c d e Hesiod, Theogony 221–225. "Also Night (Nyx) bare the destinies (Moirai), and ruthless avenging Fates (Keres), who give men at their birth both evil and good to have, and they pursue the transgressions of men and gods... until they punish the sinner with a sore penalty." online The Theogony of Hesiod. Transl. Hugh Evelyn White (1914) 221–225.

- ^ Plato, Republic 617c (trans. Shorey) (Greek philosopher 4th century BC): Theoi Project – Ananke.

- ^ Quintus Smyrnaeus. The Fall of Troy. 13. 545 ff.CS1 maint: location (link)

- ^ a b Aeschylus, Prometheus Bound, 510–518: "Not in this way is Moira (Fate) who brings all to fulfillment, destined to complete this course. Skill is weaker far than Ananke (necessity). Yes in that even he (Zeus) cannot escape what is foretold." Theoi Project – Ananke

- ^ Simplicius, In Physica 24.13. The Greek peers of Anaximander echoed his sentiment with the belief in natural boundaries beyond which not even the gods could operate: Bertrand Russell (1946). A history of Western Philosophy, and its connections with Political and Social Circumstances from the earliest times to the Present Day. New York: Simon and Schuster, p. 148.

- ^ Moira, Online Etymology Dictionary

- ^ merit, Online Etymology Dictionary

- ^ Iliad, 9.318:Lidell,Scott A Greek English Lexicon: μοῖρα,

- ^ Odyssey 19.152: :Lidell,Scott A Greek English Lexicon: μοῖρα

- ^ The citizents of Sparta were called omoioi (equals), indicating that they had equal parts ("isomoiria" ἰσομοιρία) of the allotted land

- ^ Iliad 16.367: :Lidell,Scott A Greek English Lexicon: μοῖρα

- ^ M.Nillson, Vol I, p.217

- ^ Euripides, Iph.Aul. V 113: " ΄'ω πότνια μοίρα καί τύχη, δαίμων τ΄εμός "Lidell,Scott A Greek English Lexicon: τύχη.

- ^ L.H.Jeffery (1976) Archaic Greece. The City-States c. 700–500 BC . Ernest Benn Ltd. London & Tonbridge p. 42 ISBN 0-510-03271-0

- ^ The expectation that there would be three was strong by the 2nd century CE: when Pausanias visited the temple of Apollo at Delphi, with Apollo and Zeus each accompanied by a Fate, he remarked "There are also images of two Moirai; but in place of the third Moira there stand by their side Zeus Moiragetes and Apollon Moiragetes."

- ^ Compare the ancient goddess Adrasteia, the "inescapable".

- ^ "Comes the blind Fury with th'abhorred shears, / And slits the thin spun life." John Milton, Lycidas, l. 75.

Works related to Lycidas at Wikisource

Works related to Lycidas at Wikisource

- ^ Plato (1992). Republic. Translated by Sorrey (Second ed.). Indianapolis, Indiana: Hackett Publishing Company, Inc. p. 617c. ISBN 978-0872201361.

- ^ Pindar, Fragmenta Chorica Adespota 5 (ed. Diehl).

- ^ a b R. G. Wunderlich (1994). The secret of Crete. Efstathiadis group, Athens pp. 290–291, 295–296. (British Edition, Souvenir Press Ltd. London 1975) ISBN 960-226-261-3

- ^ Burkert, Walter. (1985). The Greek Religion, Harvard University Press. pp 32–47

- ^ a b "Not yet is thy fate (moira) to die and meet thy doom" (Ilias 7.52), "But thereafter he (Achilleus) shall suffer whatever Fate (Aisa) spun for him at his birth, when his mother bore him": (Ilias 20.128 ): M. Nilsson. (1967). Die Geschichte der Griechischen Religion Vol I, C.F.Beck Verlag., Műnchen pp. 363–364

- ^ a b "But thereafter he shall suffer whatever Fate (Aisa) and the dread Spinners spun with her thread for him at his birth, when his mother bore him." (Odyssey 7.198)

- ^ "Easily known is the seed of that man for whom the son of Cronos spins the seed of good fortune at marriage and at birth." (Odyssey, 4.208 ): M.Nilsson. (1967). "Die Geschichte der Griechischen Religion". C.F.Beck Verlag., München pp. 363–364

- ^ a b M.Nilsson. (1967). "Die Geschichte der Griechischen Religion". C.F.Beck Verlag., München pp. 114, 200

- ^ "If a lady loosened a knot in the woof, she could liberate the leg of her hero. But if she tied a knot, she could stop the enemy from moving. ":Harrison, D. & Svensson, K. (2007): Vikingaliv. Fälth & Hässler, Värnamo. P. 72 ISBN 978-91-27-35725-9

- ^ M.Nilsson. (1967). "Die Geschichte der Griechischen Religion". C.F.Beck Verlag., München pp. 363–364

- ^ M. I. Finley (2002). The world of Odysseus. New York Review Books, New York, p. 39 f. (PDF file).

- ^ "Man's life is a day. What is he, what is he not? A shadow in a dream is man": Pindar, Pythionikos VIII, 95-7. Cf. C. M. Bowra (1957). The Greek experience. The World publishing company, Cleveland and New York, p. 64.

- ^ a b c Martin P. Nilsson (1967). Die Geschichte der griechischen Religion. Vol. 1. C. F. Beck, Munich, pp. 361–368.

- ^ Iliad 16.705: "Draw back noble Patrolos, it is not your lot (aisa) to sack the city of the Trojan chieftains, nor yet it will be that of Achilleus, who is far better than you are": C. Castoriades (2004). Ce qui fait la Grèce. 1, D'Homère a Héraclite. Séminaires 1982–1983 (= La creation humaine, 2). Éditions du Seuil, Paris, p. 300.

- ^ Iliad 16.433: "Ah, woe is me, for that it is fated that Sarpedon, dearest of men to me, be slain by Patroclus, son of Menoetius! And in twofold wise is my heart divided in counsel as I ponder in my thought whether I shall snatch him up while yet he liveth and set him afar from the tearful war in the rich land of Lycia, or whether I shall slay him now beneath the hands of the son of Menoetius."

- ^ Morrison, J. V. (1997). "Kerostasia, the Dictates of Fate, and the Will of Zeus in the Iliad". Arethusa. 30 (2): 276–296. doi:10.1353/are.1997.0008.

- ^ Iliad 24.527–33; cf. C. M. Bowra (1957). The Greek experience. The World publishing company, Cleveland and New York, p. 53.

- ^ Iliad 19.87: "Howbeit it is not I that am at fault, but Zeus and Fate (Moira) and Erinys, that walketh in darkness, seeing that in the midst of the place of gathering they cast upon my soul fierce blindness on that day, when of mine own arrogance I took from Achilles his prize."

- ^ Iliad 24.131: "For I tell thee, thou shall not thyself be long in life, but even nowdoth death stand hard by thee and mighty fate (moíra krataiá)".

- ^ Iliad 24.209: "On this wise for him did mighty fate spin with her thread at his birth, when myself did bear him, that he should glut swift-footed dogs far from his parents, in the abode of a violent man."

- ^ a b Theogony 901; The Theogony of Hesiod. Translated by Hugh Evelyn White (1914), 901–906 (online text).

- ^ a b M. I. Finley (1978) The world of Odysseus rev.ed. New York Viking Press p.78 Note.

- ^ a b In the Odyssey, Themistes: "dooms, things laid down originally by divine authority", the themistes of Zeus. Body: council of elders who stored in the collective memory. Thesmos: unwritten law, based on precedent. Cf. L. H. Jeffery (1976). Archaic Greece. The City-States c. 700–500 BC. Ernest Benn Ltd., London & Tonbridge, p. 42. ISBN 0-510-03271-0.

- ^ Τέκμωρ (Τekmor): fixed mark or boundary, end post, purpose (τέκμαρ).

- ^ Old English: takn "sign, mark"; English: token "sign, omen". Compare Sanskrit, Laksmi. Entry "token", in Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ^ Alcman, frag. 5 (from Scholia), translated by Campbell, Greek Lyric, vol. 2; cf. entry "Ananke" in the Theoi Project.

- ^ Orphica. Theogonies, frag. 54 (from Damascius). Greek hymns 3rd to 2nd centuries BC; cf. entry "Ananke" in the Theoi Project.

- ^ Pseudo-Apollodorus, story of Meleager in Bibliotheke 1.65.

- ^ Braswell, Bruce Karl (1991). "Meleager and the Moirai: A Note on Ps.-Apollodorus 1. 65". Hermes. 119 (4): 488–489. JSTOR 4476850.

- ^ Pausanias, 3.11. 10–11.

- ^ Pausanias, 8.21.3.

- ^ Pindar, Nemean VII 1–4

- ^ "Theoi Project Moirai". Theoi.com. Retrieved 2013-01-24.

- ^ Kerenyi 1951:32.

- ^ Hesiod, Theogony, 904.

- ^ "Zeus obviously had to assimilate this spinning Goddess, and he made them into his daughters, too, although not by all accounts, for even he was bound ultimately by Fate", observe Ruck and Staples (1994:57).

- ^ Apollodorus, 1.6.1–2.

- ^ Ilias X 209 ff. O.Crusius Rl, Harisson Prolegomena 5.43 ff: M. Nillson (1967). Die Geschichte der Griechischen Religion. Vol I . C.F.Beck Verlag. München pp. 217, 222

- ^ This is similar to the famous scene in the Egyptian book of the dead, although the conception is different. Anubis weighs the sins of a man's heart against the feather of truth. If man's heart weighs down, then he is devoured by a monster: Taylor, John H. (Editor- 2009), Ancient Egyptian Book of the Dead: Journey through the afterlife. British Museum Press, London, 2010. pp. 209, 215 ISBN 978-0-7141-1993-9

- ^ M.P.Nilsson, "Zeus-Schiksalwaage ". Homer and Mycenea D 56. The same belief in Kismet. Also the soldiers in the World-War believed that they wouldn't die by a bullet, unless their name was written on the bullet: M. Nillson (1967). Die Geschichte der Griechischen Religion. Vol I . C.F.Beck Verlag. München pp. 366, 367

- ^ H.J. Rose, Handbook of Greek Mythology, p.24

- ^ Herodotus, Histories I 91

- ^ Diels-Kranz. Fr.420

- ^ The Greek is Moiragetes (Pausanias, 5.15.5).

- ^ Pausanias, v.15.5.

- ^ "There is a sanctuary of Themis, with an image of white marble; adjoining it is a sanctuary of the Fates, while the third is of Zeus of the Market. Zeus is made of stone; the Fates have no images." (Pausanias, ix.25.4).

- ^ Pausanias, Description of Greece 2. 4. 7 (trans. Jones).

- ^ Pausanias, Description of Greece 9. 25. 4.

- ^ Pausanias, Description of Greece 3. 11. 10.

- ^ Pausanias, Description of Greece 5. 15. 5.

- ^ Pausanias, Description of Greece 8. 37. 1

- ^ Pausanias, Description of Greece 10. 24. 4

- ^ Apollonius Rhodius, Argonautica 4. 1216 ff (trans. Rieu) (Greek epic C3rd B.C.)

- ^ Pausanias, Description of Greece 2. 11. 3 - 4

- ^ Online Etymology Dictionary, s.v. "fate", "fairy".

- ^ Völuspá 20; cf. Henry Adams Bellows' translation for The American-Scandinavian Foundation with clickable names (online text). Archived 2007-07-18 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Swedish Etymological dictionary

- ^ Online Etymology Dictionary, s. v. "shall".

- ^ Nordisk familjebook (1913). Uggleupplagan. 19. Mykenai-Newpada. (online text).

- ^ Davidson H. R. Ellis (1988). Myths and symbols in Pagan Europe. Early Scandinavian and Celtic Religions. Manchester University Press, p. 58–61. ISBN 0-7190-2579-6.

- ^ Keres, derived from the Greek verb kērainein (κηραίνειν) meaning "to be destroyed". Compare Kēr (κηρ), "candle". M. Nilsson (1967). Vol I, pp. 218, 366.

- ^ Landow, John (2001). Norse Mythology, a guide to the ghosts, heroes, rituals and beliefs. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-515382-0.

- ^ Online Etymology Dictionary, s. v. "wyrd".

- ^ Latin vertere and Russian vreteno; cf. Online Etymology Dictionary, s. v. "versus".

- ^ Beowulf: A New Verse Translation. Translated by Heaney, Seamus (2001 ed.). New York City: W.W. Norton. 2001. ISBN 0-393-32097-9.

Beowulf: A New Verse Translation.

- ^ The Wanderer Archived 2012-04-02 at the Wayback Machine. Alternative translation by Clifford A. Truesdell IV

- ^ Coddon, Karin S. (Oct 1989). "'Unreal Mockery': Unreason and the Problem of Spectacle in Macbeth". ELH. Johns Hopkins University Press. 56 (3): 485–501. doi:10.2307/2873194.

- ^ "Theoi project Hecate". Theoi.com. Retrieved 2013-01-24.

- ^ William Arthur Heidel (1929). The Day of Yahweh: A Study of Sacred Days and Ritual Forms in the Ancient Near East, p. 514. American Historical Association.

- ^ Martin Nilsson (1967). Die Geschichte der griechischen Religion. Vol. 1. C. F. Beck, Munich, p. 499 f.

- ^ Greimas Algirdas Julien (1992). Of gods and men. Studies in Lithuanian Mythology. Indiana University Press, p. 111. ISBN 0-253-32652-4.

- ^ Related to "Iaksmlka", "mark, sign or token" (Rigveda X, 71,2): Monier Williams. Sanskrit-English Dictionary.

- ^ Bojtar Endre (1999). Forward to the past. A cultural history of Baltic people. CEU Press, p. 301. ISBN 963-9116-42-4.

- ^ Cf. Ramakrishna (1965:153–168), James (1969:35–36)

- ^ Duchesne-Guillemin, Jacques (1963), "Heraclitus and Iran", History of Religions, 3 (1): 34–49, doi:10.1086/462470

- ^ Boyce, Mary (1970). "Zoroaster the Priest". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies. London, England: University of London. 33 (1): 22–38. doi:10.1017/S0041977X00145100.

- ^ Bunson, Matthew (1996). Angels A to Z. New York City: Crown Publishing. ISBN 978-0517885376.

- ^ Mahony (1998:3).

- ^ See the philological work of Own Barfield, e.g Poetic Diction or Speaker's Meaning

- ^ Hermann Oldenberg (1894). Die Religion des Veda. Wilhelm Hertz, Berlin, pp. 30, 195–198.

- ^ a b Brown, W. N. (1992). "Some Ethical Concepts for the Modern World from Hindu and Indian Buddhist Tradition" in: Radhakrishnan, S. (Ed.) Rabindranath Tagore: A Centenary Volume 1861 – 1961. Calcutta: Sahitya Akademi. ISBN 81-7201-332-9.

- ^ Ramakrishna, G. (1965). "Origin and Growth of the Concept of Ṛta in Vedic Literature". Doctoral Dissertation: University of Mysore Cf.

- ^ Gods and Myths of Ancient Egypt, Robert A. Armour, American Univ in Cairo Press, p167, 2001, ISBN 977-424-669-1

- ^ Morenz, Siegfried (1992). Egyptian Religion. Translated by Keep, Ann E. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press. pp. 117–125. ISBN 0-8014-8029-9.

- ^ Taylor, John H., ed. (2010). Ancient Egyptian Book of the Dead: Journey through the afterlife. London, England: British Museum Press. pp. 209, 215. ISBN 978-0-7141-1989-2.

References[edit]

- Armour, Robert A, 2001, Gods and Myths of Ancient Egypt, American Univ. in Cairo Press, ISBN 977-424-669-1.

- Homer. The Iliad with an English translation. A. T. Murray, Ph.D. (1924), in two volumes. Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd.

- Homer. The Odyssey with an English translation. A. T. Murray, Ph.D. (1919), in two volumes. Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd.

- Thomas Blisniewski, 1992. Kinder der dunkelen Nacht: Die Ikonographie der Parzen vom späten Mittelalter bis zum späten 18. Jahrhundert. (Cologne) Iconography of the Fates from the late Middle Ages to the end of the 18th century.

- Markos Giannoulis, 2010. Die Moiren. Tradition und Wandel des Motivs der Schicksalsgöttinnen in der antiken und byzantinischen Kunst, Ergänzungsband zu Jahrbuch für Antike und Christentum, Kleine Reihe 6 (F. J. Dölger Institut). Aschendorff Verlag, Münster, ISBN 978-3-402-10913-7.

- Robert Graves, Greek Myths.

- Jane Ellen Harrison, Prolegomena to the Study of Greek Religion 1903. Chapter VI, "The Maiden-Trinities".

- L. H. Jeffery, 1976. Archaic Greece. The City-States c. 700–500 BC . Ernest Benn Ltd. London & Tonbridge, ISBN 0-510-03271-0.

- Karl Kerenyi, 1951. The Gods of the Greeks (Thames and Hudson).

- Martin P. Nilsson,1967. Die Geschichte der Griechischen Religion. Vol I, C.F. Beck Verlag., München.

- Bertrand Russell, 1946. A history of Western Philosophy, and its connections with Political and Social Circumstances from the earliest times to the Present Day. New York. Simon & Schuster p. 148

- Harry Thurston Peck, Harper's Dictionary of Classical Antiquities, 1898. perseus.tufts.edu

- Herbert Jennings Rose, Handbook of Greek Mythology, 1928.

- Carl Ruck and Danny Staples, The World of Classical Myth, 1994.

- William Smith, Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology, 1870, article on Moira, ancientlibrary.com

- R. G. Wunderlich (1994). The secret of Crete. Efstathiadis group, Athens pp. 290–291, 295–296. (British Edition, Souvenir Press Ltd. London 1975) ISBN 960-226-261-3

External links[edit]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Moirai. |