Oceanus

| Oceanus | |

|---|---|

The Titan god of the river Oceanos | |

| Member of the Titans | |

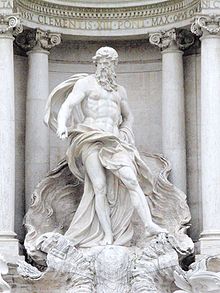

Oceanus in the Trevi Fountain, Rome | |

| Other names | Ogen or Ogenus |

| Abode | River Oceanus |

| Personal information | |

| Parents | Uranus and Gaia |

| Siblings |

|

| Consort | Tethys |

| Offspring | Thetis, Metis, Amphitrite, Dione, Pleione, Nede, Nephele, Amphiro, and the other Oceanids, Inachus, Amnisos and the other Potamoi |

| Roman equivalent | Oceanus |

In Greek mythology, Oceanus /oʊˈsiːənəs/[1] (Greek: Ὠκεανός,[2] also Ὠγενός, Ὤγενος, or Ὠγήν)[3] was the Titan son of Uranus and Gaia, the husband of his sister the Titan Tethys, and the father of the river gods and the Oceanids, as well as being the great river which encircled the entire world.

Genealogy[edit]

Oceanus was the eldest of the Titan offspring of Uranus (Sky) and Gaia (Earth).[4] Hesiod lists his Titan siblings as Coeus, Crius, Hyperion, Iapetus, Theia, Rhea, Themis, Mnemosyne, Phoebe, Tethys, and Cronus.[5] Oceanus married his sister Tethys, and was by her the father of numerous sons, the river gods and numerous daughters, the Oceanids.[6]

According to Hesiod, there were three thousand (i.e. innumerable ) river gods.[7] These included: Achelous, the god of the Achelous River, the largest river in Greece, who gave his daughter in marriage to Alcmaeon[8] and was defeated by Heracles in a wrestling contest for the right to marry Deianira;[9] Alpheus, who fell in love with the nymph Arethusa and pursued her to Syracuse where she was transformed into a spring by Artemis;[10] and Scamander who fought on the side of the Trojans during the Trojan War and got offended when Achilles polluted his waters with a large number of Trojan corpses, overflowed his banks nearly drowning Achilles.[11]

According to Hesiod, there were also three thousand Oceanids.[12] These included: Metis, Zeus' first wife, whom Zeus impregnated with Athena and then swallowed;[13] Eurynome, Zeus' third wife, and mother of the Charites;[14] Doris, the wife of Nereus and mother of the Nereids;[15] Callirhoe, the wife of Chrysaor and mother of Geryon;[16] Clymene, the wife of Iapetus, and mother of Atlas, Menoetius, Prometheus, and Epimetheus;[17] Perseis, wife of Helios and mother of Circe and Aeetes;[18] Idyia, wife of Aeetes and mother of Medea;[19] and Styx, goddess of the river Styx, and the wife of Pallas and mother of Zelus, Nike, Kratos, and Bia.[20]

According to Epimenides' Theogony, Oceanus was the father, by Gaia, of the Harpies.[21] Oceanus was also said to be the father, by Gaia, of Triptolemus.[22] Nonnus, in his poem Dionysiaca, described "the lakes" as "liquid daughters cut off from Oceanos".[23]

| Oceanus's immediate family, according to Hesiod's Theogony [24] |

|---|

Primeval father?[edit]

Passages in a section of the Iliad called the Deception of Zeus, suggest the possibility that Homer knew a tradition in which Oceanus and Tethys (rather than Uranus and Gaia, as in Hesiod) were the primeval parents of the gods.[30] Twice Homer has Hera describe the pair as "Oceanus, from whom the gods are sprung, and mother Tethys".[31] According to M. L. West, these lines suggests a myth in which Oceanus and Tethys are the "first parents of the whole race of gods."[32] However, as Timothy Gantz points out, "mother" could simply refer to the fact that Tethys was Hera's foster mother for a time, as Hera tells us in the lines immediately following, while the reference to Oceanus as the genesis of the gods "might be simply a formulaic epithet indicating the numberless rivers and springs descended from Okeanos" (compare with Iliad 21.195–197).[33] But, in a later Iliad passage, Hypnos also describes Oceanus as "genesis for all", which, according to Gantz, is hard to understand as meaning other than that, for Homer, Oceanus was the father of the Titans.[34]

Plato, in his Timaeus, provides a genealogy (probably Orphic) which perhaps reflected an attempt to reconcile this apparent divergence between Homer and Hesiod, in which Uranus and Gaia are the parents of Oceanus and Tethys, and Oceanus and Tethys are the parents of Cronus and Rhea and the other Titans, as well as Phorcys.[35] In his Cratylus, Plato quotes Orpheus as saying that Oceanus and Tethys were "the first to marry", possibly also reflecting an Orphic theogony in which Oceanus and Tethys, rather than Uranus and Gaia, were the primeval parents.[36] Plato's apparent inclusion of Phorcys as a Titan (being the brother of Cronus and Rhea), and the mythographer Apollodorus's inclusion of Dione, the mother of Aphrodite by Zeus, as a thirteenth Titan,[37] suggests an Orphic tradition in which the Titan offspring of Oceanus and Tethys consisted of Hesiod's twelve Titans, with Phorcys and Dione taking the place of Oceanus and Tethys.[38]

According to Epimenides, the first two beings, Night and Aer, produced Tartarus, who in turn produced two Titans (possibly Oceanus and Tethys) from whom came the world egg.[39]

Mythology[edit]

When Cronus, the youngest of the Titan's, overthrew his father Uranus, thereby becoming the ruler of the cosmos, according to Hesiod, none of the other Titans participated in the attack on Uranus.[40] However according to the mythographer Apollodorus, all the Titans—except Oceanus—attacked Uranus.[41] Proclus, in his commentary on Plato's Timaeus, quotes several lines of a poem (probably Orphic) which has an angry Oceanus brooding aloud as to whether he should join Cronus and the other Titans in the attack on Uranus. And, according to Proclus, Oceanus did not in fact take part in the attack.[42]

Oceanus seemingly also did not join the Titans in the Titanomachy, the great war between the Cronus and his fellow Titans, and Zeus and his fellow Olympians, for control of the cosmos; and following the war, although Cronus and the other Titans were imprisoned, Oceanus certainly seems to have remained free.[43] In Hesiod, Oceanus sends his daughter Styx, with her children Zelus (Envy), Nike (Victory), Cratos (Power), and Bia (Force), to fight on Zeus' side against the Titans,[44] And in the Iliad, Hera says that during the war she was sent to Oceanus and Tethys for safekeeping.[45]

Sometime after the war, Aeschylus' Prometheus Bound, has Oceanus visit his nephew the enchained Prometheus, who is being punished by Zeus for his theft of fire.[46] Oceanus arrives riding a winged steed,[47] saying that he is sympathetic to Prometheus' plight and wishes to help him if he can.[48] But Prometheus mocks Oceanus, asking him: "How did you summon courage to quit the stream that bears your name and the rock-roofed caves you yourself have made"[49] Oceanus advises Prometheus to humble himself before the new ruler Zeus, and so avoid making his situation any worse. But Prometheus replies: "I envy you because you have escaped blame for having dared to share with me in my troubles."[50]

According to Pherecydes, while Heracles was travelling in Helios's golden cup, on his way to Erytheia to fetch the cattle of Geryon, Oceanus challenged Heracles by sending high waves rocking the cup, but Heracles threatened to shoot Oceanus with his bow, and Oceanus in fear stopped.[51]

Geography[edit]

Although sometimes treated as a person (such as Oceanus visiting Prometheus in Aeschylus' Prometheus Bound, see above) Oceanus is more usually considered to be a place,[52] that is, as the great world-encircling river.[53] Twice Hesiod calls Oceanus "the perfect river" (τελήεντος ποταμοῖο),[54] and Homer refers to the "stream of the river Oceanus" (ποταμοῖο λίπεν ῥόον Ὠκεανοῖο).[55] Both Hesiod and Homer call Oceanus "backflowing" (ἀψορρόου), since, as the great stream encircles the earth, it flows back into itself.[56] Hesiod also calls Oceanus "deep-swirling" (βαθυδίνης),[57] while Homer calls him "deep-flowing" (βαθυρρόου).[58] Homer says that Oceanus "bounds the Earth",[59] and Oceanus was depicted on the shield of Achilles, encircling its rim,[60] and so also on the shield of Heracles.[61]

Both Hesiod and Homer locate Oceanus at the ends of the earth, near Tartarus, in the Theogony,[62] or near Elysium, in the Iliad,[63] and in the Odyssey, has to be crossed in order to reach the "dank house of Hades".[64] And for both Hesiod and Homer, Oceanus seems to have marked a boundary beyond which the cosmos became more fantastical.[65] The Theogony has such fabulous creatures as the Hesperides, with their golden apples, the three-headed giant Geryon, and the snake-haired Gorgons, all residing "beyond glorious Ocean".[66] While Homer located such exotic tribes as the Cimmerians, the Aethiopians, and the Pygmies as living nearby Oceanus.[67]

In Homer, Helios the sun, rises from Oceanus in the east,[68] and at the end of the day sinks back into Oceanus in the west,[69] and the stars bathe in the "stream of Ocean".[70] According to later sources, after setting, Helios sails back along Oceanus during the night from west to east.[71]

Just as Oceanus the god was the father of the river gods, Oceanus the river was said to be the source of all other rivers, and in fact all sources of water, both salt and fresh.[72] According to Homer, from Oceanus "all rivers flow and every sea, and all the springs and deep wells".[73] Being the source of rivers and springs would seem logically to require that Oceanus was himself a freshwater river, and so different from the salt sea, and in fact Hesiod seems to distinguish between Oceanus and Pontus, the personification of the sea.[74] However elsewhere the distinction between fresh and salt water seems not to apply. For example, in Hesiod Nereus and Thaumus, both sons of Pontus, marry daughters of Oceanus, and in Homer (who makes no mention of Pontus), Thetis, the daughter of Nereus, and Eurynome the daughter of Oceanus, live together.[75] In any case, Oceanus came also to be identified with the sea.[76]

Iconography[edit]

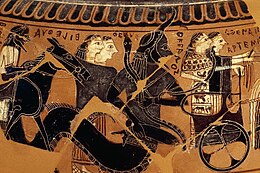

Oceanus is represented, identified by inscription, as part of an illustration of the wedding of Peleus and Thetis on the early sixth century BC Attic black-figure "Erskine" dinos by Sophilos (British Museum 1971.111–1.1).[78] Oceanus appears near the end of a long procession of gods and goddesses arriving at the palace of Peleus for the wedding. Oceanus follows a chariot driven by Athena and containing Artemis. Oceanus has bull horns, holds a snake in his left hand and a fish in his right, and has the body of a fish from the waist down. He is closely followed by Tethys and Eileithyia, with Hephaestus following on his mule ending the procession.

Oceanus also appears, as part of a very similar procession of Peleus and Thetis' wedding guests, on another early sixth century BC Attic black-figure pot, the François Vase (Florence 4209).[80] As in Sophilos' dinos, Oceanus appears at the end of the long procession, following after the last chariot, with Hephaestus on his mule bringing up the rear. Although little remains of Oceanus, he was apparently shown here with a bull's head.[81] The similarity in the order of the wedding guests on these two vases, as well as on the fragments a second Sophilos vase (Athens Akr 587), suggests the possibility of a literary source.[82]

Oceanus is depicted (labeled) as one of the gods fighting the Giants in the Gigantomachy frieze of the second century BC Pergamon Altar.[83] Oceanus stands half nude, facing right, battling a giant falling to the right. Nearby Oceanus are fragments of a figure thought to be Tethys: a part of a chiton below Oceanus' left arm and a hand clutching a large tree branch visible behind Oceanus' head.

In Hellenistic and Roman mosaics, this Titan was often depicted as having the upper body of a muscular man with a long beard and horns (often represented as the claws of a crab) and the lower body of a serpent (cfr. Typhon).[citation needed] In Roman mosaics, such as that from Bardo, he might carry a steering-oar and cradle a ship.[citation needed]

Cosmography[edit]

Oceanus appears in Hellenic cosmography as well as myth. Cartographers continued to represent the encircling equatorial stream much as it had appeared on Achilles' shield.[84]

Herodotus was skeptical about the physical existence of Oceanus and rejected the reasoning—proposed by some of his coevals—according to which the uncommon phenomenon of the summerly Nile flood was caused by the river's connection to the mighty Oceanus. Speaking about the Oceanus myth itself he declared:

As for the writer who attributes the phenomenon to the ocean, his account is involved in such obscurity that it is impossible to disprove it by argument. For my part I know of no river called Ocean, and I think that Homer, or one of the earlier poets, invented the name, and introduced it into his poetry.[85]

Some scholars[who?] believe that Oceanus originally represented all bodies of salt water, including the Mediterranean Sea and the Atlantic Ocean, the two largest bodies known to the ancient Greeks.[citation needed] However, as geography became more accurate, Oceanus came to represent the stranger, more unknown waters of the Atlantic Ocean (also called the "Ocean Sea"), while the newcomer of a later generation, Poseidon, ruled over the Mediterranean Sea.[citation needed]

Late attestations for an equation with the Black Sea abound, the cause being – as it appears – Odysseus' travel to the Cimmerians whose fatherland, lying beyond the Oceanus, is described as a country divested from sunlight.[86] In the fourth century BC, Hecataeus of Abdera writes that the Oceanus of the Hyperboreans is neither the Arctic nor Western Ocean, but the sea located to the north of the ancient Greek world, namely the Black Sea, called "the most admirable of all seas" by Herodotus,[87] labelled the "immense sea" by Pomponius Mela[88] and by Dionysius Periegetes,[89] and which is named Mare majus on medieval geographic maps. Apollonius of Rhodes, similarly, calls the lower Danube the Kéras Okeanoío ("Gulf" or "Horn of Oceanus").[90]

Hecataeus of Abdera also refers to a holy island, sacred to the Pelasgian (and later, Greek) Apollo, situated in the easternmost part of the Okeanós Potamós, and called in different times Leuke or Leukos, Alba, Fidonisi or Isle of Snakes. It was on Leuke, in one version of his legend, that the hero Achilles, in a hilly tumulus, was buried (which is erroneously connected to the modern town of Kiliya, at the Danube delta). Accion ("ocean"), in the fourth century AD Gaulish Latin of Avienus' Ora maritima, was applied to great lakes.[91]

Etymology[edit]

According to M. L. West, the etymology of Oceanus is "obscure" and "cannot be explained from Greek".[92] The use by Pherecydes of Syros of the form "Ogenos" (Ὠγενός) for the name lends support for the name being a loanword.[93] However, according to West, no "very convincing" foreign models have been found.[94] A Semitic derivation has been suggested by several scholars,[95] while R. S. P. Beekes has suggested a loanword from the Aegean Pre-Greek non-Indo-European substrate.[96] Nevertheless, Michael Janda sees possible Indo-European connections.[97]

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ "Oceanus". Merriam-Webster Dictionary..

- ^ LSJ s.v. Ὠκεανός.

- ^ West 1966, p. 201 on line 133; LSJ s.v. Ωγενος.

- ^ Hesiod, Theogony 132–138; Apollodorus, 1.1.3. Compare with Diodorus Siculus, 5.66.1–3, which says that the Titans (including Oceanus) "were born, as certain writers of myths relate, of Uranus and Gê, but according to others, of one of the Curetes and Titaea, from whom as their mother they derive the name".

- ^ Apollodorus adds Dione to this list, while Diodorus Siculus leaves out Theia.

- ^ Hesiod, Theogony 337–370; Homer, Iliad 200–210, 14.300–304, 21.195–197; Aeschylus, Prometheus Bound 137–138 (Sommerstein, pp. 458, 459), Seven Against Thebes 310–311 (Sommerstein, pp. 184, 185); Hyginus, Fabulae Preface (Smith and Trzaskoma, p. 95). For Oceanus as father of the river gods, see also: Diodorus Siculus, 4.69.1, 72.1. For Oceanus as father of the Oceanids, see also: Apollodorus, 1.2.2; Callimachus, Hymn 3.40–45 (Mair, pp. 62, 63); Apollonius of Rhodes, Argonautica, 242–244 (Seaton, pp. 210, 211). For a discussion of these offspring of Oceanus and Tethys see Hard, pp. 43.

- ^ Hard, p. 40; Hesiod, Theogony 364–368, which says there are "as many" rivers as the "three thousand neat-ankled daughters of Ocean", and at 330–345, names 25 of these river gods: Nilus, Alpheus, Eridanos, Strymon, Maiandros, Istros, Phasis, Rhesus, Achelous, Nessos, Rhodius, Haliacmon, Heptaporus, Granicus, Aesepus, Simoeis, Peneus, Hermus, Caicus, Sangarius, Ladon, Parthenius, Evenus, Aldeskos, and Scamander. Compare with Acusilaus fr. 1 Fowler [= FGrHist 2 1 = Vorsokr. 9 B 21 = Macrobius, Saturnalia 5.18.9–10], which says that from Oceanus and Tethys, "spring three thousand rivers".

- ^ Apollodorus, 3.7.5.

- ^ Apollodorus, 1.8.1, 2.7.5.

- ^ Smith, s.v. "Alpheius".

- ^ Homer, Iliad 20.74, 21.211 ff..

- ^ Hesiod, Theogony 346–366, which names 41 Oceanids: Peitho, Admete, Ianthe, Electra, Doris, Prymno, Urania, Hippo, Clymene, Rhodea, Callirhoe, Zeuxo, Clytie, Idyia, Pasithoe, Plexaura, Galaxaura, Dione, Melobosis, Thoe, Polydora, Cerceis, Plouto, Perseis, Ianeira, Acaste, Xanthe, Petraea, Menestho, Europa, Metis, Eurynome, Telesto, Chryseis, Asia, Calypso, Eudora, Tyche, Amphirho, Ocyrhoe, and Styx.

- ^ Hesiod, Theogony 886–900; Apollodorus, 1.3.6.

- ^ Hesiod, Theogony 907–909; Apollodorus, 1.3.1. Other sources give the Charites other parents, see Smith, s.v. "Charis".

- ^ Hesiod, Theogony 240–264; Apollodorus, 1.2.7.

- ^ Hesiod, Theogony 286–288; Apollodorus, 2.5.10.

- ^ Hesiod, Theogony 351, however according to Apollodorus, 1.2.3, another Oceanid, Asia was their mother by Iapetus.

- ^ Hesiod, Theogony 956–957; Apollodorus, 1.9.1.

- ^ Hesiod, Theogony 958–962; Apollodorus, 1.9.23.

- ^ Hesiod, Theogony 383–385; Apollodorus, 1.2.4.

- ^ Gantz, p. 18.

- ^ Apollodorus, 1.5.2, attributing Pherecydes [= Pherecydes fr. 53 Fowler; Pausanias, 1.14.3, attributing "Musaeus" presumably Musaeus of Athens.

- ^ Nonnus, 'Dionysiaca 6.252.

- ^ Hesiod, Theogony 132–138, 337–411, 453–520, 901–906, 915–920; Caldwell, pp. 8–11, tables 11–14.

- ^ One of the Oceanid daughters of Oceanus and Tethys, at Hesiod, Theogony 351. However, according to Apollodorus, 1.2.3, a different Oceanid, Asia was the mother, by Iapetus, of Atlas, Menoetius, Prometheus, and Epimetheus.

- ^ Although usually, as here, the daughter of Hyperion and Theia, in the Homeric Hymn to Hermes (4), 99–100, Selene is instead made the daughter of Pallas the son of Megamedes.

- ^ According to Plato, Critias, 113d–114a, Atlas was the son of Poseidon and the mortal Cleito.

- ^ In Aeschylus, Prometheus Bound 18, 211, 873 (Sommerstein, pp. 444–445 n. 2, 446–447 n. 24, 538–539 n. 113) Prometheus is made to be the son of Themis.

- ^ Although, at Hesiod, Theogony 217, the Moirai are said to be the daughters of Nyx (Night).

- ^ Fowler 2013, pp. 8, 11; Hard, pp. 36–37, p. 40; West 1997, p. 147; Gantz, p. 11; Burkert 1995, pp. 91–92; West 1983, pp. 119–120.

- ^ Homer, Iliad 14.201, 302 [= 201].

- ^ West 1997, p. 147.

- ^ Gantz, p. 11.

- ^ Gantz, p. 11; Homer, Iliad 14.245.

- ^ Gantz, pp. 11–12; West 1983, pp. 117–118; Fowler 2013, p. 11; Plato, Timaeus 40d–e.

- ^ West 1983, pp. 118–120; Fowler 2013, p. 11; Plato, Cratylus 402b [= Orphic fr. 15 Kern].

- ^ Apollodorus, 1.1.3, 1.3.1.

- ^ Gantz, p. 743.

- ^ Fowler 2013, pp. 7–8.

- ^ Hesiod, Theogony 165–181.

- ^ Hard, p. 37; Apollodorus, 1.1.4.

- ^ Gantz, pp. 12, 28; West 1983, p. 130; Orphic fr. 135 Kern.

- ^ Fowler 2013, p. 11; Hard, p. 37; Gantz, pp. 28, 46; West 1983, p. 119.

- ^ Hard, p. 37; Gantz, p. 28; Hesiod, Theogony 337–398. The translations of the names used here follow Caldwell, p. 8.

- ^ Hard, p. 40; Gantz, p. 11; Homer, Iliad 14.200–204.

- ^ Gantz, p. 28; Hard, p. 40; Aeschylus (?), Prometheus Bound 286–398.

- ^ Aeschylus (?), Prometheus Bound 286–289, 395 (which describes the beast as "four-footed"). Hard, p. 40 suggests that Oceanus' steed is a griffin or griffin-like, while Gantz, p. 28, suggests griffin or hippocamp.

- ^ Aeschylus (?), Prometheus Bound 290–299.

- ^ Aeschylus (?), Prometheus Bound 301–303.

- ^ Aeschylus (?), Prometheus Bound 332–333.

- ^ Gantz, p. 404; Frazer's note 7 to Apollodorus 2.5.10; Hard, p. 40.

- ^ Gantz, p. 28.

- ^ Hard, pp. 36, 40; Gantz, p. 27; West 1966, p. 201 on line 133.

- ^ Hesiod, Theogony 242, 959.

- ^ Homer, Iliad 12.1.

- ^ LSJ s.v. ἀψόρροος; Hesiod, Theogony 767; Homer, Iliad 18.399, Odyssey 20.65.

- ^ LSJ s.v. βαθυδίνης, Hesiod, Theogony 133.

- ^ LSJ s.v. βαθυρρόου; Homer, Iliad 7.422 = Odyssey 19.434.

- ^ Homer, Odyssey 11.13.

- ^ Gantz, p. 27; Homer, Iliad 18.607–608.

- ^ Hesiod, Shield of Heracles 314–317.

- ^ Gantz, p. 27; Hesiod, Theogony 729–792.

- ^ Homer, Iliad 14.200–201, 4.563–568.

- ^ Gantz, pp. 27, 123, 124; Homer, Odyssey 10.508–512, 11.13–22.

- ^ As George M. A. Hanfmann, Oxford Classical Dictionary s.v. Oceanus, p. 744, puts it: "the land where reality ends and everything is fabulous".

- ^ Hesiod, Theogony 215–216 (Hesperides), 287–299 (Geryon), 274 (Gorgons).

- ^ Cimmerians: Odyssey 11.13–14; Aethiopians: Iliad 23.205–206, Odyssey 1.22–24 (since Oceanus is where the sun, Helios Hyperion, rises and sets); Pygmies: Iliad 1.5–6.

- ^ Homer, Iliad 7.421–422, = Odyssey 19.433–434.

- ^ Homer, Iliad 8.485, 18.239–240.

- ^ Homer, Iliad 5.5–6, 18.485–489. Compare with Homer, Iliad 23.205 which has Iris, the personification of the rainbow, say "I must go back unto the streams of Oceanus".

- ^ Gantz, pp. 27, 30.

- ^ Hard, p. 36; Gantz, p. 27.

- ^ Homer, Iliad 21.195–197.

- ^ West 1966, p. 201 on line 133.

- ^ Gantz, p. 27; Homer, Iliad 398–399.

- ^ West 1966, p. 201 on line 133.

- ^ LIMC 6487 (Okeanos 1); Beazley Archive 350099; Avi 4748.

- ^ LIMC 6487 (Tethys I (S) 1); Beazley Archive 350099; Avi 4748; Gantz, pp. 28, 229–230; Burkert, p. 202; Williams, pp. 27 fig. 34, 29, 31–32; Perseus: London 1971.11–1.1 (Vase); British Museum 1971,1101.1.

- ^ LIMC 617 (Okeanos 7).

- ^ LIMC 1602 (Okeanos 3); Beazley Archive 300000; AVI 3576.

- ^ Gantz, pp. 28, 229–230; Beazley, p. 27; Perseus Florence 4209 (Vase). Compare with Euripides, Orestes 1375–1379, which calls Oceanus "bull-headed" (ταυρόκρανος ).

- ^ Gantz, pp. 229–230; Williams, p. 33; Perseus: London 1971.11-1.1 (Vase).

- ^ LIMC 617 (Okeanos 7); Jentel, p. 1195; Queyrel, p. 67; Pollit, p. 96.

- ^ Livio Catullo Stecchini. "Ancient Cosmology". www.metrum.org. Retrieved 2017-03-30.

- ^ Histories II, 21 ff.

- ^ Homer. Odyssey, 11.13–19

- ^ Herodotus. The Histories, 4.85

- ^ De situ orbis I, 19.

- ^ Orbis Descriptio V, 165.

- ^ Apollonius of Rhodes. Argonautica, 4.282

- ^ Mullerus in Cl. Ptolemaei Geographia, ed. Didot, p. 235.

- ^ West 1997, 146; see also Hard, p. 40

- ^ Fowler 2013, p. 11; West 1997, p. 146; Pherecydes of Syros, Vorsokr. 7 B 2.

- ^ West 1997, p. 146.

- ^ Fowler 2013, p. 11; West 1997, pp. 146–147.

- ^ Fowler 2013, p. 11 n. 34; Beekes, Etymological Dictionary of Greek s.v.

- ^ Janda, pp. 57 ff.

References[edit]

- Aeschylus, Persians. Seven against Thebes. Suppliants. Prometheus Bound. Edited and translated by Alan H. Sommerstein. Loeb Classical Library No. 145. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2009. ISBN 978-0-674-99627-4. Online version at Harvard University Press.

- Aeschylus (?), Prometheus Bound in Aeschylus, with an English translation by Herbert Weir Smyth, Ph. D. in two volumes. Vol 2. Cambridge, Massachusetts, Harvard University Press. 1926. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Apollodorus, Apollodorus, The Library, with an English Translation by Sir James George Frazer, F.B.A., F.R.S. in 2 Volumes. Cambridge, Massachusetts, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1921. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Anonymous, The Homeric Hymns and Homerica with an English Translation by Hugh G. Evelyn-White. Homeric Hymns. Cambridge, MA.,Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1914. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Apollonius Rhodius, Argonautica translated by Robert Cooper Seaton (1853-1915), R. C. Loeb Classical Library Volume 001. London, William Heinemann Ltd, 1912. Online version at the Topos Text Project.

- Apollonius of Rhodes, Apollonius Rhodius: the Argonautica, translated by Robert Cooper Seaton, W. Heinemann, 1912. Internet Archive.

- Beazley, John Davidson, The Development of Attic Black-figure, Volume 24, University of California Press, 1951. ISBN 9780520055933.

- Beekes, Robert S. P., Etymological Dictionary of Greek, Brill, 2009.

- Burkert, Walter The Orientalizing Revolution: Near Eastern Influence on Greek Culture in the Early archaic Age, Harvard University Press, 1992, pp. 91–93.

- Caldwell, Richard, Hesiod's Theogony, Focus Publishing/R. Pullins Company (June 1, 1987). ISBN 978-0-941051-00-2.

- Callimachus, Callimachus and Lycophron with an English translation by A. W. Mair ; Aratus, with an English translation by G. R. Mair, London: W. Heinemann, New York: G. P. Putnam 1921. Internet Archive.

- Diodorus Siculus, Diodorus Siculus: The Library of History. Translated by C. H. Oldfather. Twelve volumes. Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press; London: William Heinemann, Ltd. 1989. Online version by Bill Thayer

- Euripides, Orestes, translated by E. P. Coleridge in The Complete Greek Drama, edited by Whitney J. Oates and Eugene O'Neill, Jr. Volume 1. New York. Random House. 1938. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Fowler, R. L. (2000), Early Greek Mythography: Volume 1: Text and Introduction, Oxford University Press, 2000. ISBN 978-0198147404.

- Fowler, R. L. (2013), Early Greek Mythography: Volume 2: Commentary, Oxford University Press, 2013. ISBN 978-0198147411.

- Freeman, Kathleen, Ancilla to Pre-Socratic Philosophers: A Complete Translation of the Fragments in Diels, Fragmente der Vorsokratiker (1948), July 13, 2012 2012, Kindle Edition.

- Gantz, Timothy, Early Greek Myth: A Guide to Literary and Artistic Sources, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996, Two volumes: ISBN 978-0-8018-5360-9 (Vol. 1), ISBN 978-0-8018-5362-3 (Vol. 2).

- Hanfmann, George M. A., s.v. Oceanus, in The Oxford Classical Dictionary, Hammond, N.G.L. and Howard Hayes Scullard (editors), second edition, Oxford University Press, 1992. ISBN 0-19-869117-3.

- Hard, Robin, The Routledge Handbook of Greek Mythology: Based on H.J. Rose's "Handbook of Greek Mythology", Psychology Press, 2004, ISBN 9780415186360. Google Books.

- Herodotus, The Histories with an English translation by A. D. Godley. Cambridge. Harvard University Press. 1920. Online version at the Topos Text Project. Greek text available at Perseus Digital Library.

- Hesiod, Theogony, in The Homeric Hymns and Homerica with an English Translation by Hugh G. Evelyn-White, Cambridge, Massachusetts, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1914. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Homer, The Iliad with an English Translation by A.T. Murray, Ph.D. in two volumes. Cambridge, Massachusetts, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann, Ltd. 1924. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Homer, The Odyssey with an English Translation by A.T. Murray, PH.D. in two volumes. Cambridge, Massachusetts, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann, Ltd. 1919. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Hyginus, Gaius Julius, Fabulae in Apollodorus' Library and Hyginus' Fabuae: Two Handbooks of Greek Mythology, Translated, with Introductions by R. Scott Smith and Stephen M. Trzaskoma, Hackett Publishing Company, 2007. ISBN 978-0-87220-821-6.

- Janda, Michael, Die Musik nach dem Chaos. Der Schöpfungsmythos der europäischen Vorzeit. Institut für Sprachwissenschaft der Universität Innsbruck, Innsbruck 2010.

- Jentel, Marie-Odile, "Tethys I", in Lexicon Iconographicum Mythologiae Classicae (LIMC) VIII.1 Artemis Verlag, Zürich and Munich, 1997. ISBN 9783760887517.

- Karl Kerenyi. The Gods of the Greeks. Thames and Hudson, 1951.

- Kern, Otto. Orphicorum Fragmenta, Berlin, 1922. Internet Archive

- Macrobius, Saturnalia, Volume II: Books 3-5, edited and translated by Robert A. Kaster, Loeb Classical Library No. 511, Cambridge, Massachusetts, Harvard University Press, 2011. Online version at Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-99649-6.

- Nonnus, Dionysiaca; translated by Rouse, W H D, I Books I–XV. Loeb Classical Library No. 344, Cambridge, Massachusetts, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1940. Internet Archive

- Pausanias, Pausanias Description of Greece with an English Translation by W.H.S. Jones, Litt.D., and H.A. Ormerod, M.A., in 4 Volumes. Cambridge, Massachusetts, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1918. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Plato, Cratylus in Plato in Twelve Volumes, Vol. 12 translated by Harold N. Fowler, Cambridge, Massachusetts, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1925. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Plato, Timaeus in Plato in Twelve Volumes, Vol. 9 translated by W.R.M. Lamb, Cambridge, Massachusetts, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1925. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Pollitt, Jerome Jordan, Art in the Hellenistic Age, Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521276726.

- Queyrel, François, L'Autel de Pergame: Images et pouvoir en Grèce d'Asie, Paris: Éditions A. et J. Picard, 2005. ISBN 2-7084-0734-1.

- West, M. L. (1966), Hesiod: Theogony, Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-814169-6.

- West, M. L. (1983), The Orphic Poems, Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19-814854-8.

- West, M. L. (1997), The East Face of Helicon: West Asiatic Elements in Greek Poetry and Myth, Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-815042-3.

- Smith, William; Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology, London (1873). Online version at the Perseus Digital Library

- Williams, Dyfri, "Sophilos in the British Museum" in Greek Vases In The J. Paul Getty Museum, Getty Publications, 1983, pp. 9–34. ISBN 0-89236-058-5.

External links[edit]

- Livio Catullo Stecchini, "Ancient Cosmology"

- . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.