Al-Aqsa Mosque

| Al-Aqsa Mosque | |

|---|---|

ٱلْمَسْجِد ٱلْأَقْصَىٰ Al-Masjid al-’Aqṣā | |

| |

| Religion | |

| Affiliation | Islam |

| Leadership | Imam Muhammad Ahmad Hussein |

| Location | |

| Location | Old City of Jerusalem |

| Administration | Jerusalem Islamic Waqf |

| Geographic coordinates | 31°46′34″N 35°14′09″E / 31.77617°N 35.23583°ECoordinates: 31°46′34″N 35°14′09″E / 31.77617°N 35.23583°E |

| Architecture | |

| Type | Mosque |

| Style | Early Islamic, Mamluk |

| Date established | 705 CE |

| Specifications | |

| Direction of façade | north-northwest |

| Capacity | 5,000+ |

| Dome(s) | two large + tens of smaller ones |

| Minaret(s) | four |

| Minaret height | 37 meters (121 ft) (tallest) |

| Materials | Limestone (external walls, minaret, facade) stalactite (minaret), Gold, lead and stone (domes), white marble (interior columns) and mosaic[1] |

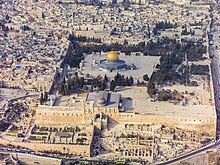

Al-Aqsa Mosque (Arabic: ٱلْمَسْجِد ٱلْأَقْصَىٰ, romanized: al-Masjid al-ʾAqṣā, IPA: [ʔælˈmæsdʒɪd ælˈʔɑqsˤɑ] (![]() listen), "the Farthest Mosque"), located in the Old City of Jerusalem, is the third holiest site in Islam. The mosque was built on top of the Temple Mount, known as the Al Aqsa Compound or Haram esh-Sharif in Islam. Muslims believe that Muhammad was transported from the Great Mosque of Mecca to al-Aqsa during the Night Journey. Islamic tradition holds that Muhammad led prayers towards this site until the 17th month after his migration from Mecca to Medina, when Allah directed him to turn towards the Kaaba in Mecca.

listen), "the Farthest Mosque"), located in the Old City of Jerusalem, is the third holiest site in Islam. The mosque was built on top of the Temple Mount, known as the Al Aqsa Compound or Haram esh-Sharif in Islam. Muslims believe that Muhammad was transported from the Great Mosque of Mecca to al-Aqsa during the Night Journey. Islamic tradition holds that Muhammad led prayers towards this site until the 17th month after his migration from Mecca to Medina, when Allah directed him to turn towards the Kaaba in Mecca.

The covered mosque building was originally a small prayer house erected by Umar, the second caliph of the Rashidun Caliphate, but was rebuilt and expanded by the Umayyad caliph Abd al-Malik and finished by his son al-Walid in 705 CE. The mosque was completely destroyed by an earthquake in 746 and rebuilt by the Abbasid caliph al-Mansur in 754. It was rebuilt again in 780. Another earthquake destroyed most of al-Aqsa in 1033, but two years later the Fatimid caliph Ali az-Zahir built another mosque whose outline is preserved in the current structure. The mosaics on the arch at the qibla end of the nave also go back to his time.

During the periodic renovations undertaken, the various ruling dynasties of the Islamic Caliphate constructed additions to the mosque and its precincts, such as its dome, facade, its minbar, minarets and the interior structure. When the Crusaders captured Jerusalem in 1099, they used the mosque as a palace and the Dome of the Rock as a church, but its function as a mosque was restored after its recapture by Saladin in 1187. More renovations, repairs and additions were undertaken in the later centuries by the Ayyubids, Mamluks, Ottomans, the Supreme Muslim Council, and Jordan. Today, the Old City is under Israeli control, but the mosque remains under the administration of the Jordanian/Palestinian-led Islamic Waqf.

The mosque is located in close proximity to historical sites significant in Judaism and Christianity, most notably the site of the Second Temple, the holiest site in Judaism. As a result, the area is highly sensitive, and has been a flashpoint in the Israeli–Palestinian conflict.[2]

Etymology

Al-Masjid al-Aqsa translates from Arabic into English as "the farthest mosque". The name refers to a chapter of the Quran called Al-Isrā’ (Arabic: ٱلْإِسْـرَاء), "The Night Journey"), in which it is said that Muhammad travelled from Mecca to "the farthest mosque", and then up to Heaven on a heavenly creature called al-Burāq ash-Sharīf (Arabic: ٱلْـبُـرَاق الـشَّـرِيْـف).[3][4]

Definition

Haram vs. Al-Aqsa

Although in its narrowest sense, the Al-Aqsa indicates the silver-domed mosque on the southern side of the Temple Mount plaza, the term "Al-Aqsa" has often been used to refer to the entire area, including the mosque, along with the Dome of the Rock, the Gates of the Temple Mount, and the four minarets. al-Masjid al-Aqsa referred not only to the mosque, but to the entire sacred sanctuary, while Al-Jâmi‘ al-Aqṣá (Arabic: ٱلْـجَـامِـع الْأَقْـصّى) referred to the specific site of the mosque.[note 1] During the period of Ottoman rule (c. early 16th century to 1917) the wider compound began to also be referred to as al-Ḥaram ash-Sharīf (Arabic: اَلْـحَـرَم الـشَّـرِيْـف, the Noble Sanctuary),[6][7]

Al-Qibli vs. Al-Aqsa

Al-Aqsa Mosque is also referred to as Al-Qibli Mosque on account of a particular building within it, the Al-Qibli Chapel (al-Jami' al-Aqsa or al-Qibli, or Masjid al-Jumah or al-Mughata).[8][9]

History

Pre-construction

The mosque is located on the Temple Mount, referred to by Muslims today as the "Haram al-Sharif" ("Noble Sanctuary"), an enclosure expanded by King Herod the Great beginning in 20 BCE.[10] In Islamic tradition, the original sanctuary is believed to date to the time of Abraham.[11]

The mosque resides on an artificial platform that is supported by arches constructed by Herod's engineers to overcome the difficult topographic conditions resulting from the southward expansion of the enclosure into the Tyropoeon and Kidron valleys.[12] At the time of the Second Temple, the present site of the mosque was occupied by the Royal Stoa, a basilica running the southern wall of the enclosure.[12] The Royal Stoa was destroyed along with the Temple during the sacking of Jerusalem by the Romans in 70 CE.

It was once thought that Emperor Justinian's "Nea Ekklesia of the Theotokos", or the New Church of the God-Bearer, dedicated to the God-bearing Virgin Mary, consecrated in 543 and commonly known as the Nea Church, was situated where al-Aqsa Mosque was later constructed. However, remains identified as those of the Nea Church were uncovered in the south part of the Jewish Quarter in 1973.[13][14]

Analysis of the wooden beams and panels removed from the mosque during renovations in the 1930s shows they are made from Cedar of Lebanon and cypress. Radiocarbon dating gave a large range of ages, some as old as 9th-century BCE, showing that some of the wood had previously been used in older buildings.[15] However, reexamination of the same beams in the 2010s gave dates in the Byzantine period.[16]

During his excavations in the 1930s, Robert Hamilton uncovered portions of a multicolor mosaic floor with geometric patterns, but didn't publish them.[16] The date of the mosaic is disputed: Zachi Dvira considers that they are from the pre-Islamic Byzantine period, while Baruch, Reich and Sandhaus favor a much later Umayyad origin on account of their similarity to a known Umayyad mosaic.[16]

Construction by the Umayyads

The current construction of the al-Aqsa Mosque is dated to the early Umayyad period of rule in Palestine. Architectural historian K. A. C. Creswell, referring to a testimony by Arculf, a Gallic monk, during his pilgrimage to Palestine in 679–82, notes the possibility that the second caliph of the Rashidun Caliphate, Umar ibn al-Khattab, erected a primitive quadrangular building for a capacity of 3,000 worshipers somewhere on the Haram ash-Sharif. However, Arculf visited Palestine during the reign of Mu'awiyah I, and it is possible that Mu'awiyah ordered the construction, not Umar. This latter claim is explicitly supported by the early Muslim scholar al-Muthahhar bin Tahir.[17]

According to several Muslim scholars, including Mujir ad-Din, al-Suyuti, and al-Muqaddasi, the mosque was reconstructed and expanded by the caliph Abd al-Malik in 690 along with the Dome of the Rock.[17][18] Guy le Strange claims that Abd al-Malik used materials from the destroyed Church of Our Lady to build the mosque and points to possible evidence that substructures on the southeast corners of the mosque are remains of the church.[18] In planning his magnificent project on the Temple Mount, which in effect would turn the entire complex into the Haram al-Sharif ("the Noble Sanctuary"), Abd al-Malik wanted to replace the slipshod structure described by Arculf with a more sheltered structure enclosing the qibla ("direction"), a necessary element in his grand scheme. However, the entire Haram al-Sharif was meant to represent a mosque. How much he modified the aspect of the earlier building is unknown, but the length of the new building is indicated by the existence of traces of a bridge leading from the Umayyad palace just south of the western part of the complex. The bridge would have spanned the street running just outside the southern wall of the Haram al-Sharif to give direct access to the mosque. Direct access from palace to mosque was a well-known feature in the Umayyad period, as evidenced at various early sites. Abd al-Malik shifted the central axis of the mosque some 40 meters (130 ft) westward, in accord with his overall plan for the Haram al-Sharif. The earlier axis is represented in the structure by the niche still known as the "mihrab of 'Umar." In placing emphasis on the Dome of the Rock, Abd al-Malik had his architects align his new al-Aqsa Mosque according to the position of the Rock, thus shifting the main north–south axis of the Noble Sanctuary, a line running through the Dome of the Chain and the Mihrab of Umar.[19]

In contrast, Creswell, while referring to the Aphrodito Papyri, claims that Abd al-Malik's son, al-Walid I, reconstructed the Aqsa Mosque over a period of six months to a year, using workers from Damascus. Most scholars agree that the mosque's reconstruction was started by Abd al-Malik, but that al-Walid oversaw its completion. In 713–14, a series of earthquakes ravaged Jerusalem, destroying the eastern section of the mosque, which was subsequently rebuilt during al-Walid's rule. In order to finance its reconstruction, al-Walid had gold from the dome of the Rock minted to use as money to purchase the material.[17] The Umayyad-built al-Aqsa Mosque most likely measured 112 x 39 meters.[19]

Earthquakes and reconstructions

In 746, the al-Aqsa Mosque was damaged in an earthquake, four years before as-Saffah overthrew the Umayyads and established the Abbasid Caliphate. The second Abbasid caliph Abu Ja'far al-Mansur declared his intent to repair the mosque in 753, and he had the gold and silver plaques that covered the gates of the mosque removed and turned into dinars and dirhams to finance the reconstruction which ended in 771. A second earthquake damaged most of al-Mansur's repairs, excluding those made in the southern portion in 774.[18][20] In 780, His successor Muhammad al-Mahdi had it rebuilt, but curtailed its length and increased its breadth.[18][21] Al-Mahdi's renovation is the first known to have written records describing it.[22] In 985, Jerusalem-born Arab geographer al-Muqaddasi recorded that the renovated mosque had "fifteen naves and fifteen gates".[20]

In 1033, there was another earthquake, severely damaging the mosque. The Fatimid caliph Ali az-Zahir rebuilt and completely renovated the mosque between 1034 and 1036. The number of naves was drastically reduced from 15 to seven.[20] Az-Zahir built the four arcades of the central hall and aisle, which presently serve as the foundation of the mosque. The central aisle was double the width of the other aisles and had a large gable roof upon which the dome—made of wood—was constructed.[17] Persian geographer, Nasir Khusraw describes the Aqsa Mosque during a visit in 1047:

The Haram Area (Noble Sanctuary) lies in the eastern part of the city; and through the bazaar of this (quarter) you enter the Area by a great and beautiful gateway (Dargah)... After passing this gateway, you have on the right two great colonnades (Riwaq), each of which has nine-and-twenty marble pillars, whose capitals and bases are of colored marbles, and the joints are set in lead. Above the pillars rise arches, that are constructed, of masonry, without mortar or cement, and each arch is constructed of no more than five or six blocks of stone. These colonnades lead down to near the Maqsurah (enclosure).[23]

Jerusalem was captured by the Crusaders in 1099, during the First Crusade. They named the mosque "Solomon's Temple", distinguishing it from the Dome of the Rock, which they named Templum Domini (Temple of God). While the Dome of the Rock was turned into a Christian church under the care of the Augustinians,[24] the al-Aqsa Mosque was used as a royal palace and also as a stable for horses. In 1119, it was transformed into the headquarters of the Templar Knights. During this period, the mosque underwent some structural changes, including the expansion of its northern porch, and the addition of an apse and a dividing wall. A new cloister and church were also built at the site, along with various other structures.[25] The Templars constructed vaulted western and eastern annexes to the building; the western currently serves as the women's mosque and the eastern as the Islamic Museum.[20]

After the Ayyubids under the leadership of Saladin reconquered Jerusalem following the siege of 1187, several repairs and renovations were undertaken at al-Aqsa Mosque. In order to prepare the mosque for Friday prayers, within a week of his capture of Jerusalem Saladin had the toilets and grain stores installed by the Crusaders at al-Aqsa removed, the floors covered with precious carpets, and its interior scented with rosewater and incense.[26] Saladin's predecessor—the Zengid sultan Nur al-Din—had commissioned the construction of a new minbar or "pulpit" made of ivory and wood in 1168–69, but it was completed after his death; Nur ad-Din's minbar was added to the mosque in November 1187 by Saladin.[27] The Ayyubid sultan of Damascus, al-Mu'azzam, built the northern porch of the mosque with three gates in 1218. In 1345, the Mamluks under al-Kamil Shaban added two naves and two gates to the mosque's eastern side.[20]

After the Ottomans assumed power in 1517, they did not undertake any major renovations or repairs to the mosque itself, but they did to the Noble Sanctuary as a whole. This included the building of the Fountain of Qasim Pasha (1527), the restoration of the Pool of Raranj, and the building of three free-standing domes—the most notable being the Dome of the Prophet built in 1538. All construction was ordered by the Ottoman governors of Jerusalem and not the sultans themselves.[28] The sultans did make additions to existing minarets, however.[28] In 1816, the mosque was restored by Governor Sulayman Pasha al-Adil after having been in a dilapidated state.[29]

Modern era

The first renovation in the 20th century occurred in 1922, when the Supreme Muslim Council under Amin al-Husayni (the Grand Mufti of Jerusalem) commissioned Turkish architect Ahmet Kemalettin Bey to restore al-Aqsa Mosque and the monuments in its precincts. The council also commissioned British architects, Egyptian engineering experts and local officials to contribute to and oversee the repairs and additions which were carried out in 1924–25 by Kemalettin. The renovations included reinforcing the mosque's ancient Umayyad foundations, rectifying the interior columns, replacing the beams, erecting a scaffolding, conserving the arches and drum of the main dome's interior, rebuilding the southern wall, and replacing timber in the central nave with a slab of concrete. The renovations also revealed Fatimid-era mosaics and inscriptions on the interior arches that had been covered with plasterwork. The arches were decorated with gold and green-tinted gypsum and their timber tie beams were replaced with brass. A quarter of the stained glass windows also were carefully renewed so as to preserve their original Abbasid and Fatimid designs.[30] Severe damage was caused by the 1837 and 1927 earthquakes, but the mosque was repaired in 1938 and 1942.[20]

On 20 July 1951, King Abdullah I was shot three times by a Palestinian gunman as he entered the mosque, killing him. His grandson Prince Hussein, was at his side and was also hit, though a medal he was wearing on his chest deflected the bullet.

On 21 August 1969, a fire was started by a visitor from Australia named Denis Michael Rohan. Rohan was a member of an evangelical Christian sect known as the Worldwide Church of God.[31] He hoped that by burning down al-Aqsa Mosque he would hasten the Second Coming of Jesus, making way for the rebuilding of the Jewish Temple on the Temple Mount. Rohan was subsequently hospitalized in a mental institution.[32] In response to the incident, a summit of Islamic countries was held in Rabat that same year, hosted by Faisal of Saudi Arabia, the then king of Saudi Arabia. The al-Aqsa fire is regarded as one of the catalysts for the formation of the Organisation of the Islamic Conference (OIC, now the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation) in 1972.[33]

In the 1980s, Ben Shoshan and Yehuda Etzion, both members of the Gush Emunim Underground, plotted to blow up the al-Aqsa mosque and the Dome of the Rock. Etzion believed that blowing up the two mosques would cause a spiritual awakening in Israel, and would solve all the problems of the Jewish people. They also hoped the Third Temple of Jerusalem would be built on the location of the mosque.[34][35] On 15 January 1988, during the First Intifada, Israeli troops fired rubber bullets and tear gas at protesters outside the mosque, wounding 40 worshipers.[36][37] On 8 October 1990, 22 Palestinians were killed and over 100 others injured by Israeli Border Police during protests that were triggered by the announcement of the Temple Mount Faithful, a group of religious Jews, that they were going to lay the cornerstone of the Third Temple.[38][39]

On 28 September 2000, then-opposition leader of Israel Ariel Sharon and members of the Likud Party, along with 1,000 armed guards, visited the al-Aqsa compound; a large group of Palestinians went to protest the visit. After Sharon and the Likud Party members left, a demonstration erupted and Palestinians on the grounds of the Haram al-Sharif began throwing stones and other projectiles at Israeli riot police. Police fired tear gas and rubber bullets at the crowd, injuring 24 people. The visit sparked a five-year uprising by the Palestinians, commonly referred to as the al-Aqsa Intifada, though some commentators, citing subsequent speeches by PA officials, particularly Imad Falouji and Arafat himself, claim that the Intifada had been planned months in advance, as early as July upon Yasser Arafat's return from Camp David talks.[40][41][42] On 29 September, the Israeli government deployed 2,000 riot police to the mosque. When a group of Palestinians left the mosque after Friday prayers (Jumu'ah,) they hurled stones at the police. The police then stormed the mosque compound, firing both live ammunition and rubber bullets at the group of Palestinians, killing four and wounding about 200.[43]

On 5 November 2014, Israeli police entered Al-Aqsa for the first time since capturing Jerusalem in 1967, said Sheikh Azzam Al-Khatib, director of the Islamic Waqf. Previous media reports of 'storming Al-Aqsa' referred to the Haram al-Sharif compound rather than the Al-Aqsa mosque itself.[44]

Architecture

The rectangular al-Aqsa Mosque and its precincts cover 14.4 hectares (36 acres), although the mosque itself is about 12 acres (5 ha) in area and can hold up to 5,000 worshippers.[45] It is 83 m (272 ft) long, 56 m (184 ft) wide.[45] Unlike the Dome of the Rock, which reflects classical Byzantine architecture, the Al-Aqsa Mosque is characteristic of early Islamic architecture.[46]

Dome

Nothing remains of the original dome built by Abd al-Malik. The present-day dome was built by az-Zahir and consists of wood plated with lead enamelwork.[17] In 1969, the dome was reconstructed in concrete and covered with anodized aluminium, instead of the original ribbed lead enamel work sheeting. In 1983, the aluminium outer covering was replaced with lead to match the original design by az-Zahir.[47]

Beneath the dome is the Al-Qibli Chapel (Arabic: المصلى القبلي al-Musalla al-Qibli); also known as al-Jami' al-Qibli Arabic: الجامع القِبْلي, a Muslim prayer hall, located in the southern part of the mosque.[48] It was built by the Rashidun caliph Umar ibn Al-Khattab in 637 CE.

Al-Aqsa's dome is one of the few domes to be built in front of the mihrab during the Umayyad and Abbasid periods, the others being the Umayyad Mosque in Damascus (715) and the Great Mosque of Sousse (850).[49] The interior of the dome is painted with 14th-century-era decorations. During the 1969 burning, the paintings were assumed to be irreparably lost, but were completely reconstructed using the trateggio technique, a method that uses fine vertical lines to distinguish reconstructed areas from original ones.[47]

Facade and porch

The facade of the mosque was built in 1065 CE on the instructions of the Fatimid caliph al-Mustansir Billah. It was crowned with a balustrade consisting of arcades and small columns. The Crusaders damaged the facade, but it was restored and renovated by the Ayyubids. One addition was the covering of the facade with tiles.[20] The second-hand material of the facade's arches includes sculpted, ornamental material taken from Crusader structures in Jerusalem.[50] The facade consists of fourteen stone arches,[3][dubious ] most of which are of a Romanesque style. The outer arches added by the Mamluks follow the same general design. The entrance to the mosque is through the facade's central arch.[51]

The porch is located at the top of[dubious ] the facade. The central bays of the porch were built by the Knights Templar during the First Crusade,[dubious ] but Saladin's nephew al-Mu'azzam Isa ordered the construction of the porch itself in 1217.[20][dubious ]

Interior

The al-Aqsa Mosque has seven aisles of hypostyle naves with several additional small halls to the west and east of the southern section of the building.[21] There are 121 stained glass windows in the mosque from the Abbasid and Fatimid eras. About a fourth of them were restored in 1924.[30] The mosaic decoration and the inscription (two lines just above the decoration near the roof as visible in the photos placed in the gallery here) on the spandrels of arche facing main entrance near main dome area which date back to Fatimid period were revealed from behind plaster work of a later date that covered them.[52] Name of Fatimid Imam is clearly visible in end part of the first line of inscription and continued in second line.

Decorated wall above mihrab near central dome facing main entrance[52]

Mention of Fatimid imam on decorated wall (top left corner first line(..al-Zahir li-Izaz din-Allaah..)continuing in second)[52]

Fatimid inscription above mihrab (top right)[52]

The mosque's interior is supported by 45 columns, 33 of which are white marble and 12 of stone.[45] The column rows of the central aisles are heavy and stunted. The remaining four rows are better proportioned. The capitals of the columns are of four different kinds: those in the central aisle are heavy and primitively designed, while those under the dome are of the Corinthian order,[45] and made from Italian white marble. The capitals in the eastern aisle are of a heavy basket-shaped design and those east and west of the dome are also basket-shaped, but smaller and better proportioned. The columns and piers are connected by an architectural rave, which consists of beams of roughly squared timber enclosed in a wooden casing.[45]

A great portion of the mosque is covered with whitewash, but the drum of the dome and the walls immediately beneath it are decorated with mosaics and marble. Some paintings by an Italian artist were introduced when repairs were undertaken at the mosque after an earthquake ravaged the mosque in 1927.[45] The ceiling of the mosque was painted with funding by King Farouk of Egypt.[51]

The minbar of the mosque was built by a craftsman named Akhtarini from Aleppo on the orders of the Zengid sultan Nur ad-Din. It was intended to be a gift for the mosque when Nur ad-Din would capture Jerusalem from the Crusaders and took six years to build (1168–74). Nur ad-Din died and the Crusaders still controlled Jerusalem, but in 1187, Saladin captured the city and the minbar was installed. The structure was made of ivory and carefully crafted wood. Arabic calligraphy, geometrical and floral designs were inscribed in the woodwork.[53] After its destruction by Rohan in 1969, it was replaced by a much simpler minbar. In January 2007, Adnan al-Husayni—head of the Islamic waqf in charge of al-Aqsa—stated that a new minbar would be installed;[54] it was installed in February 2007.[55] The design of the new minbar was drawn by Jamil Badran based on an exact replica of the Saladin Minbar and was finished by Badran within a period of five years.[53] The minbar itself was built in Jordan over a period of four years and the craftsmen used "ancient woodworking methods, joining the pieces with pegs instead of nails, but employed computer images to design the pulpit [minbar]."[54]

Ablution fountain

The mosque's main ablution fountain, known as al-Kas ("the Cup"), is located north of the mosque between it and the Dome of the Rock. It is used by worshipers to perform wudu, a ritual washing of the hands, arms, legs, feet, and face before entry into the mosque. It was first built in 709 by the Umayyads, but in 1327–28 Governor Tankiz enlarged it to accommodate more worshipers. Although originally supplied with water from Solomon's Pools near Bethlehem, it currently receives water from pipes connected to Jerusalem's water supply.[56] In the 20th-century, al-Kas was provided taps and stone seating.[57]

The Fountain of Qasim Pasha, built by the Ottomans in 1526 and located north of the mosque on the platform of the Dome of the Rock, was used by worshipers for ablution and for drinking until the 1940s. Today, it stands as a monumental structure.[58]

Religious significance in Islam

In Islam, the term "al-Aqsa Mosque" refers to the entire Noble Sanctuary. The mosque is believed to be the second house of prayer constructed after the Masjid al-Haram in Mecca. Post-Rashidun-era Islamic scholars traditionally identified the mosque as the site referred to in the sura (Quranic chapter) al-Isra ("the Night Journey"). This specific verse in the Quran cemented the significant religious importance of al-Aqsa in Islam.[citation needed] The specific passage reads "Praise be to Him who made His servant journey in the night from the sacred sanctuary to the remotest sanctuary." In early Islam the story of Muhammad's ascension from Al-Aqsa Mosque—'"the farthest place of prayer" (al masjid al aqsa) was understood as relating to the Jewish Temple in Jerusalem. There was a significant Muslims group disputed this connection, identifying "the farthest place of prayer" as a reference to a site in the heavens.[59]

Sahih al-Bukhari: Volume 4, Book 55, Hadith Number 585[60][61]

Isra and Mi'raj

According to the Quran and Islamic traditions, Al-Aqsa Mosque is the place from which Muhammad went on a night journey (al-isra) during which he rode on Buraq, who took him from Mecca to al-Aqsa.[62] Muhammad tethered Buraq to the Western Wall and prayed at al-Aqsa Mosque and after he finished his prayers, the angel Jibril (Gabriel) traveled with him to heaven, where he met several other prophets and led them in prayer.[63][64][65]

First qibla

The historical significance of the al-Aqsa Mosque in Islam is further emphasized by the fact that Muslims turned towards al-Aqsa when they prayed for a period of 16 or 17 months after migration to Medina in 624; it thus became the qibla ("direction") that Muslims faced for prayer.[66] Muhammad later prayed towards the Kaaba in Mecca after receiving a revelation during a prayer session [Quran 2:142–151][67] in the Masjid al-Qiblatayn.[68][69] The qibla was relocated to the Kaaba where Muslims have been directed to pray ever since.[70]

The altering of the qibla was precisely the reason the Rashidun caliph Umar, despite identifying the mosque which Muhammad used to ascend to Heaven upon his arrival at the Noble Sanctuary in 638, neither prayed facing it nor built any structure upon it. This was because the significance of that particular spot on the Noble Sanctuary was superseded in Islamic jurisprudence by the Kaaba in Mecca after the change of the qibla towards that site.[71]

According to early Quranic interpreters and what is generally accepted as Islamic tradition, in 638 CE Umar, upon entering a conquered Jerusalem, consulted with Ka'ab al-Ahbar—a Jewish convert to Islam who came with him from Medina—as to where the best spot would be to build a mosque. Al-Ahbar suggested to him that it should be behind the Rock "... so that all of Jerusalem would be before you." Umar replied, "You correspond to Judaism!" Immediately after this conversation, Umar began to clean up the site—which was filled with trash and debris—with his cloak, and other Muslim followers imitated him until the site was clean. Umar then prayed at the spot where it was believed that Muhammad had prayed before his night journey, reciting the Quranic sura Sad.[71] Thus, according to this tradition, Umar thereby reconsecrated the site as a mosque.[72]

Because of the holiness of Noble Sanctuary itself—being a place where David and Solomon had prayed—Umar constructed a small prayer house in the southern corner of its platform, taking care to avoid allowing the Rock to come between the mosque and the direction of Kaaba so that Muslims would face only Mecca when they prayed.[71]

Religious status

Jerusalem is recognized as a sacred site in Islam. Though the Quran does not mention Jerusalem by name, it has been understood by Islamic scholars since the earliest times that many passages in the Quran refer to Jerusalem.[73] Jerusalem is also mentioned many times in the hadith. Some academics attribute the holiness of Jerusalem to the rise and expansion of a certain type of literary genre, known as al-Fadhail or history of cities. The Fadhail of Jerusalem inspired Muslims, especially during the Umayyad period, to embellish the sanctity of the city beyond its status in the holy texts.[74] Others point to the political motives of the Umayyad dynasty which led to the sanctification of Jerusalem in Islam.[75]

Later medieval scripts, as well as modern-day political tracts, tend to classify al-Aqsa Mosque as the third holiest site in Islam.[76] For example, Sahih al-Bukhari quotes Abu Darda as saying: "the Prophet of God Muhammad said a prayer in the Sacred Mosque (in Mecca) is worth 100,000 prayers; a prayer in my mosque (in Medina) is worth 1,000 prayers; and a prayer in al-Aqsa Mosque is worth 500 prayers more than in any other mosque".[77] In addition, the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation refers to the al-Aqsa Mosque as the third holiest site in Islam (and calls for Arab sovereignty over it).[78]

Current situations

Administration

The Waqf Ministry of Jordan held control of the al-Aqsa Mosque until the 1967 Six-Day War. After Israel's victory in that war, Israel transferred the control of the mosque and the northern Noble Sanctuary to the Islamic waqf trust, who are independent of the Israeli government. However, Israeli Security Forces are permitted to patrol and conduct searches within the perimeter of the mosque. After the 1969 arson attack, the waqf employed architects, technicians and craftsmen in a committee that carry out regular maintenance operations. The Islamic Movement in Israel and the waqf have attempted to increase Muslim control of the Temple Mount as a way of countering Israeli policies and the escalating presence of Israeli security forces around the site since the Second Intifada. Some activities included refurbishing abandoned structures and renovating.[79]

Muhammad Ahmad Hussein is the head imam and manager of the al-Aqsa Mosque and was assigned the role of Grand Mufti of Jerusalem in 2006 by Palestinian president Mahmoud Abbas.[80] Ownership of the al-Aqsa Mosque is a contentious issue in the Israel-Palestinian conflict. Israel claims sovereignty over the mosque along with all of the Temple Mount (Noble Sanctuary), but Palestinians hold the custodianship of the site through the Islamic waqf. During the negotiations at the 2000 Camp David Summit, Palestinians demanded complete ownership of the mosque and other Islamic holy sites in East Jerusalem.[81]

Current Imams:

Sheikh Abu Yusuf Sneia, Sheikh Ali Al Abbasi, Sheikh Sa'eed Qalqeeli, Sheikh Walid

Access

Muslim residents of Israel and Palestinians living in East Jerusalem are normally allowed to enter the Temple Mount and pray at the al-Aqsa Mosque without restrictions.[82] Due to security measures, the Israeli government occasionally prevents certain groups of Muslims from reaching al-Aqsa by blocking the entrances to the complex; the restrictions vary from time to time. At times restrictions have prevented all men under 50 and women under 45 from entering, but married men over 45 are allowed. Sometimes the restrictions are enforced on the occasion of Friday prayers,[83][84] other times they are over an extended period of time.[83][85][86] Restrictions are most severe for Gazans, followed by restrictions on those from West Bank. The Israeli government states that the restrictions are in place for security reasons.[82]

Until 2000, non-Muslim visitors could enter the Al-Aqsa Mosque by getting a ticket from the Waqf. That procedure ended when the Second Intifada began. Fifteen years later, negotiation between Israel and Jordan might result in allowing visitors to enter once again.[87]

Excavations

Several excavations outside the Temple Mount took place following the 1967 War. In 1970, Israeli authorities commenced intensive excavations outside the walls next to the mosque on the southern and western sides. Palestinians believed that tunnels were being dug under the Al-Aqsa Mosque in order to undermine its foundations, which was denied by Israelis, who claimed that the closest excavation to the mosque was some 70 meters (230 ft) to its south.[88] The Archaeological Department of the Israeli Ministry of Religious Affairs dug a tunnel near the western portion of the mosque in 1984.[39] According to UNESCO's special envoy to Jerusalem Oleg Grabar, buildings and structures on the Temple Mount are deteriorating due mostly to disputes between the Israeli, Palestinian and Jordanian governments over who is actually responsible for the site.[89]

In February 2007, the Department started to excavate a site for archaeological remains in a location where the government wanted to rebuild a collapsed pedestrian bridge leading to the Mughrabi Gate, the only entrance for non-Muslims into the Temple Mount complex. This site was 60 meters (200 ft) away from the mosque.[90] The excavations provoked anger throughout the Islamic world, and Israel was accused of trying to destroy the foundation of the mosque. Ismail Haniya—then Prime Minister of the Palestinian National Authority and Hamas leader—called on Palestinians to unite to protest the excavations, while Fatah said they would end their ceasefire with Israel.[91] Israel denied all charges against them, calling them "ludicrous".[92]

See also

- Haram (site)

- Islamic architecture

- Islam in Israel

- Islam in the Palestinian territories

- Jordanian art

- List of the oldest mosques in the world

- Masjid an-Nabawi

- Mosque of Omar

- Palestinian nationalism

- Religious significance of the Syrian region

Notes

- ^ According to historian Oleg Grabar, "It is only at a relatively late date that the Muslim holy space in Jerusalem came to be referred to as al-haram al-sharif (literally, the Noble Sacred Precinct or Restricted Enclosure, often translated as the Noble Sanctuary and usually simply referred to as the Haram). While the exact early history of this term is unclear, we know that it only became common in Ottoman times, when administrative order was established over all matters pertaining to the organization of the Muslim faith and the supervision of the holy places, for which the Ottomans took financial and architectural responsibility. Before the Ottomans, the space was usually called al-masjid al-aqsa (the Farthest Mosque), a term now reserved to the covered congregational space on the Haram, or masjid bayt al-maqdis (Mosque of the Holy City) or, even, like Mecca's sanctuary, al-masjid al-ḥarâm,"[5]

References

- ^ Al-Ratrout, H. A., The Architectural Development of Al-Aqsa Mosque in the Early Islamic Period, ALMI Press, London, 2004.

- ^ The Archaeology of the Holy Land: From the Destruction of Solomon's Temple to the Muslim Conquest, Cambridge University Press, Jodi Magness, page 355

- ^ a b "Al-Aqsa Mosque, Jerusalem". Atlas Travel and Tourist Agency. Archived from the original on 26 July 2008. Retrieved 29 June 2008.

- ^ "Lailat al Miraj". BBC News. BBC MMVIII. Retrieved 29 June 2008.

- ^ Grabar 2000, p. 203.

- ^ Schieck, Robert (2008) in Geographical Dimension of Islamic Jerusalem, Cambridge Scholars Publishing; see also Omar, Abdallah (2009) al-Madkhal li-dirasat al-Masjid al-Aqsa al-Mubarak, Beirut: Dar al-Kotob al-Ilmiyaah; also by the same author the Atlas of Al-Aqsa Mosque (2010)

- ^ Jarrar 1998, p. 85.

- ^ "Al-Aqsa Mosque". Al Habtoor Group. Al-Shindagah.com. 2007.

- ^ Mahdi Abdul Hadi: "Al-Aqsa Mosque, also referred to as Al-Haram Ash-Sharif (the Noble Sanctuary), comprises the entire area within the compound walls (a total area of 144,000 m2) - including all the mosques, prayer rooms, buildings, platforms and open courtyards located above or under the grounds - and exceeds 200 historical monuments pertaining to various Islamic eras. According to Islamic creed and jurisprudence, all these buildings and courtyards enjoy the same degree of sacredness since they are built on Al-Aqsa’s holy grounds. This sacredness is not exclusive to the physical structures allocated for prayer, like the Dome of the Rock or Al-Qibly Mosque (the mosque with the large silver dome)"

Mahdi Abdul Hadi Palestinian Academic Society for the Study of International Affairs; Tim Marshall: "Many people believe that the mosque depicted is called the Al-Aqsa; however, a visit to one of Palestine's most eminent intellectuals, Mahdi F. Abdul Hadi, clarified the issue. Hadi is chairman of the Palestinian Academic Society for the Study of International Affairs, based in East Jerusalem. His offices are a treasure trove of old photographs, documents, and symbols. He was kind enough to spend several hours with me. He spread out maps of Jerusalem's Old City on a huge desk and homed in on the Al-Aqsa compound, which sits above the Western Wall. “The mosque in the Al- Aqsa [Brigades] flag is the Dome of the Rock. Everyone takes it for granted that it is the Al-Aqsa mosque, but no, the whole compound is Al-Aqsa, and on it are two mosques, the Qibla mosque and the Dome of the Rock, and on the flags of both Al-Aqsa Brigades and the Qassam Brigades, it is the Dome of the Rock shown,” he said." Tim Marshall (4 July 2017). A Flag Worth Dying For: The Power and Politics of National Symbols. Simon and Schuster. pp. 151–. ISBN 978-1-5011-6833-8. - ^ Hartsock, Ralph (27 August 2014). "The temple of Jerusalem: past, present, and future". Jewish Culture and History. 16 (2): 199–201. doi:10.1080/1462169X.2014.953832.

- ^ Michigan Consortium for Medieval and Early Modern Studies (1986). Goss, V. P.; Bornstein, C. V. (eds.). The Meeting of Two Worlds: Cultural Exchange Between East and West During the Period of the Crusades. 21. Medieval Institute Publications, Western Michigan University. p. 208. ISBN 0918720583.

- ^ a b Ehud Netzer (October 2008). Architecture of Herod, the Great Builder. Baker Academic. pp. 161–171. ISBN 978-0-8010-3612-5.

- ^ Nahman Avigad (1977). "A Building Inscription of the Emperor Justinian and the Nea in Jerusalem". Israel Exploration Journal. 27 (2/3): 145–151.

- ^ Robert Schick (2007). "Byzantine Jerusalem". In Zeidan Kafafi; Robert Schick (eds.). Jerusalem before Islam. Archaeopress. p. 175.

- ^ N. Liphschitz, G. Biger, G. Bonani and W. Wolfli, Comparative Dating Methods: Botanical Identification and 14C Dating of Carved Panels and Beams from the Al-Aqsa Mosque in Jerusalem, Journal of Archaeological Science, (1997) 24, 1045–1050.

- ^ a b c Yuval Baruch, Ronny Reich & Débora Sandhaus. "A Decade of Archaeological Exploration on the Temple Mount, Tel Aviv". Tel Aviv. 45 (1): 3–22. doi:10.1080/03344355.2018.1412057.

- ^ a b c d e Elad, Amikam. (1995). Medieval Jerusalem and Islamic Worship Holy Places, Ceremonies, Pilgrimage BRILL, pp. 29–43. ISBN 90-04-10010-5.

- ^ a b c d le Strange, Guy. (1890). Palestine under the Moslems, pp. 80–98.

- ^ a b Grafman and Ayalon, 1998, pp. 1–15.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Ma'oz, Moshe and Nusseibeh, Sari. (2000). Jerusalem: Points of Friction, and Beyond BRILL. pp. 136–138. ISBN 90-411-8843-6.

- ^ a b Al-Aqsa Mosque Archived 3 January 2009 at the Wayback Machine Archnet Digital Library.

- ^ Jeffers, 2004, pp. 95–96.

- ^ "The travels of Nasir-i-Khusrau to Jerusalem, 1047 C.E". Homepages.luc.edu. Archived from the original on 19 July 2011. Retrieved 13 July 2010.

- ^ Pringle, 1993, p. 403.

- ^ Boas, 2001, p. 91.

- ^ Hancock, Lee. Saladin and the Kingdom of Jerusalem: the Muslims recapture the Holy Land in AD 1187. 2004: The Rosen Publishing Group. ISBN 0-8239-4217-1

- ^ Madden, 2002, p. 230.

- ^ a b Al-Aqsa Guide Archived 6 October 2008 at the Wayback Machine Friends of Al-Aqsa 2007.

- ^ Pappe, Ilan (2012). "Chapter 2: In the Shadow of Acre and Cairo: The Third Generation". The Rise and Fall of a Palestinian Dynasty: The Huyaynis 1700 – 1948. Saqi Books. ISBN 978-0-86356-801-5.

- ^ a b Yuvaz, 1996, pp. 149–153.

- ^ "The Burning of Al-Aqsa". Time Magazine. 29 August 1969. p. 1. Retrieved 1 July 2008.

- ^ "Madman at the Mosque". Time Magazine. 12 January 1970. Retrieved 3 July 2008.

- ^ Esposito, 1998, p. 164.

- ^ Dumper, 2002, p. 44.

- ^ Sprinzak 2001, pp. 198–199.

- ^ OpenDocument Letter Archived 28 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine Dated 18 January 1988 from the Permanent Observer for the Palestine Liberation Organization to the United Nations Office at Geneva Addressed to the Under-Secretary-General for Human Rights Ramlawi, Nabil. Permanent Observer of the Palestine Liberation Organization to the United Nations Office at Geneva.

- ^ Palestine Facts Timeline, 1963–1988 Archived 29 September 2008 at the Wayback Machine Palestinian Academic Society for the Study of International Affairs.

- ^ Dan Izenberg, Jerusalem Post, 19 July 1991

- ^ a b Amayreh, Khaled. Catalogue of provocations: Israel's encroachments upon the Al-Aqsa Mosque have not been sporadic, but, rather, a systematic endeavor Archived 15 November 2008 at the Wayback Machine Al-Ahram Weekly. February 2007.

- ^ "Provocative' mosque visit sparks riots". BBC News. BBC MMVIII. 28 September 2000. Retrieved 1 July 2008.

- ^ Khaled Abu Toameh. "How the war began". Archived from the original on 28 March 2006. Retrieved 29 March 2006.

- ^ "In a Ruined Country". The Atlantic Monthly Online. September 2005.

- ^ Dean, 2003, p. 560.

- ^ "Israeli occupation forces breach Al-Aqsa Mosque for the first time since 1967". Middle East Monitor. Archived from the original on 23 December 2014. Retrieved 23 December 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f Al-Aqsa Mosque Life in the Holy Land.

- ^ Gonen, 2003, p. 95.

- ^ a b Al-Aqsa Mosque Restoration Archived 3 January 2009 at the Wayback Machine Archnet Digital Library.

- ^ "What are Al Masjid Al Aqsa and the Dome of the Rock?". visitmasjidalaqsa.com. Archived from the original on 17 April 2019. Retrieved 16 April 2019.

- ^ Necipogulu, 1998, p. 14.

- ^ Hillenbrand, Carolle. (2000). The Crusades: The Islamic Perspective Routeledge, p. 382 ISBN 0-415-92914-8.

- ^ a b Al-Aqsa Mosque, Jerusalem Sacred Destinations.

- ^ a b c d The Encyclopaedia of Islam; By H. A. R. Gibb, E. van Donzel, P. J. Bearman, J. van Lent; p.151

- ^ a b Oweis, Fayeq S. (2002) The Elements of Unity in Islamic Art as Examined Through the Work of Jamal Badran Universal-Publishers, pp. 115–117. ISBN 1-58112-162-8.

- ^ a b Wilson, Ashleigh. Lost skills revived to replicate a medieval minbar. The Australian. 2008-11-11. Access date: 8 July 2011.

- ^ Mikdadi, Salwa D. Badrans: A Century of Tradition and Innovation, Palestinian Art Court Archived 4 January 2009 at the Wayback Machine Riweq Bienalle in Palestine.

- ^ Dolphin, Lambert. The Temple Esplanade.

- ^ Gonen, 2003, p. 28.

- ^ Qasim Pasha Sabil Archived 25 May 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Archnet Digital Library.

- ^ Frederick S. Colby (6 August 2008). Narrating Muhammad's Night Journey: Tracing the Development of the Ibn 'Abbas Ascension Discourse. SUNY Press. p. 15. ISBN 978-0-7914-7788-5.

- ^ Sahih al-Bukhari, 5:58:226

- ^ "A history of the Al Asqa Mosque". Arab World Books.

- ^ Richard C. Martin; Said Amir Arjom; Marcia Hermansen; Abdulkader Tayob; Rochelle Davis; John Obert Voll, eds. (2 December 2003). Encyclopedia of Islam and the Muslim World. Macmillan Reference USA. p. 482. ISBN 978-0-02-865603-8.

- ^ Religion and the Arts, Volume 12. 2008. pp. 329–342

- ^ Vuckovic, Brooke Olson (30 December 2004). Heavenly Journeys, Earthly Concerns: The Legacy of the Mi'raj in the Formation of Islam (Religion in History, Society and Culture). Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-96785-3.

- ^ Sahih al-Bukhari, 9:93:608

- ^ Buchanan, Allen (2004). States, Nations, and Borders: The Ethics of Making Boundaries. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-52575-6.

- ^ Shah, 2008, p. 39.

- ^ Raby, 2004, p. 298.

- ^ Patel, 2006, p. 13.

- ^ Asali, 1990, p. 105.

- ^ a b c Mosaad, Mohamed. Bayt al-Maqdis: An Islamic Perspective pp. 3–8

- ^ The Furthest Mosque, The History of Al – Aqsa Mosque From Earliest Times Mustaqim Islamic Art & Literature. 5 January 2008.

- ^ el-Khatib, Abdallah (1 May 2001). "Jerusalem in the Qur'ān". British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies. 28 (1): 25–53. doi:10.1080/13530190120034549. Retrieved 17 November 2006.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Talhami, Ghada Hashem (February 2000). "The Modern History of Islamic Jerusalem: Academic Myths and Propaganda". Middle East Policy Journal. Blackwell Publishing. VII (14). ISSN 1061-1924. Archived from the original on 16 November 2006. Retrieved 17 November 2006.

- ^ Silverman, Jonathan (6 May 2005). "The opposite of holiness". Retrieved 17 November 2006.

- ^ Doninger, Wendy (1 September 1999). Merriam-Webster's Encyclopedia of World Religions. Merriam-Webster. p. 70. ISBN 0-87779-044-2.

- ^ Important Sites: Al-Aqsa Mosque

- ^ "Resolution No. 2/2-IS". Second Islamic Summit Conference. Organisation of the Islamic Conference. 24 February 1974. Archived from the original on 14 October 2006. Retrieved 17 November 2006.

- ^ Social Structure and Geography Palestinian Academic Society for the Study of International Affairs.

- ^ Yaniv Berman, "Top Palestinian Muslim Cleric Okays Suicide Bombings", Media Line, 23 October 2006.

- ^ Camp David Projections Archived 11 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine Palestinian Academic Society for the Study of International Affairs. July 2000.

- ^ a b Mohammed Mar'i (14 August 2010). "Thousands barred from praying in Al-Aqsa". Arab News. Archived from the original on 18 November 2010.

- ^ a b "Fresh clashes mar al-Aqsa prayers". BBC News. 9 October 2009.

- ^ "Israel police, fearing unrest, limit al-Aqsa worship". i24news. 14 April 2014. Archived from the original on 10 August 2016.

- ^ "Israel boosts security in east Jerusalem".

- ^ Ramadan prayers at al-Aqsa mosque BBC News. 5 September 2008.

- ^ "Report: Israel, Jordan in Talks to Readmit non-Muslim Visitors to Temple Mount Sites". Haaretz. 30 June 2015.

- ^ Finkelstein, Israel (26 April 2011). "In the Eye of Jerusalem's Archaeological Storm". The Jewish Daily Forward. Retrieved 2 May 2011.

- ^ Abdel-Latif, Omayma (8 August 2001). "'Not impartial, not scientific': As political conflict threatens the survival of monuments in the world's most coveted city, Omayma Abdel-Latif speaks to UNESCO's special envoy to Jerusalem". Al-Ahram Weekly. Al-Ahram. Archived from the original on 5 June 2011. Retrieved 15 July 2011.

- ^ Lis, Jonathan (2 December 2007). "Majadele: Jerusalem mayor knew Mugrabi dig was illegal". Haaretz. Haaretz. Archived from the original on 12 June 2008. Retrieved 1 July 2008.

- ^ Rabinovich, Abraham (8 February 2007). "Palestinians unite to fight Temple Mount dig". The Australian. Archived from the original on 16 January 2009. Retrieved 1 July 2008.

- ^ Friedman, Matti (14 October 2007). "Israel to resume dig near Temple Mount". USA Today. Retrieved 1 July 2008.

Bibliography

- 'Asali, Kamil Jamil (1990). Jerusalem in History. Interlink Books. ISBN 1-56656-304-6.

- Auld, Sylvia (2005). "The Minbar of al-Aqsa: Form and Function". In Hillenbrand, R (ed.). Image and Meaning in Islamic Art. London: Altajir Trust. pp. 42–60.

- Boas, Adrian (2001). Jerusalem in the Time of the Crusades: Society, Landscape and Art in the holy city under Frankish rule. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-23000-4.

- Dean, Lucy (2003). The Middle East and North Africa 2004. Routledge. ISBN 1-85743-184-7.

- Dumper, Michael (2002). The Politics of Sacred Space: The Old City of Jerusalem in the Middle East. Lynne Rienner Publishers. ISBN 1-58826-226-X.

- Esposito, John L. (1998). Islam and Politics. Syracuse University Press. ISBN 0-8156-2774-2.

- Gonen, Rivka (2003). Contested Holiness. KTAV Publishing House. ISBN 0-88125-799-0.

- Grabar, Oleg (2000). "The Haram al-Sharif: An Essay in Interpretation" (PDF). Bulletin of the Royal Institute for Inter-Faith Studies. Constructing the Study of Islamic Art. 2 (2). Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 April 2016. Retrieved 20 January 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jacobs, Daniel (2009). Jerusalem. Penguin. ISBN 978-1-4053-8001-0.

- Jarrar, Sabri (1998). "Suq al-Ma'rifa: An Ayyubid Hanbalite Shrine in Haram al-Sharif". In Necipoğlu, Gülru (ed.). Muqarnas: An Annual on the Visual Culture of the Islamic World (Illustrated, annotated ed.). Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-11084-7.

- Jeffers, H. (2004). Contested Holiness: Jewish, Muslim, and Christian Perspective on the Temple. KTAV Publishing House. ISBN 978-0-88125-799-1.

- Madden, Thomas F. (2002). The Crusades: The Essential Readings. Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 0-631-23023-8.

- Meri, Josef W.; Bacharach, Jeri L. (2006). Medieval Islamic civilization: An Encyclopedia. Taylor and Francis. ISBN 0-415-96691-4.

- Yavuz, Yildirim (1996). "The Restoration Project of the Masjid al-Aqsa by Mimar Kemalettin (1922–26)". In Necipoğlu, Gülru (ed.). Muqarnas, Volume 13: An Annual on the Visual Culture of the Islamic World. Brill. ISBN 90-04-10633-2.

- Netzer, Ehud (2008). The Architecture of Herod, the Great Builder. Baker Academic. ISBN 978-0-8010-3612-5.

- Patel, Ismail (2006). Virtues of Jerusalem: An Islamic Perspective. Al-Aqsa Publishers. ISBN 0-9536530-2-1.

- Pringle, Denys (1993). The Churches of the Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem: Volume 3, The City of Jerusalem: A Corpus. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-39038-5.

- Raby, Julian (2004). Essays in Honour of J. M. Rogers. Brill. ISBN 90-04-13964-8.

- Sprinzak, Ehud (2001). "From Messianic Pioneering to Vigilante Terrorism: The Case of the Gush Emunim Underground". In Rapoport, David (ed.). Inside Terrorist Organizations. Routledge. ISBN 0-7146-8179-2.

- Shah, Niaz A. (2008). Self-defense in Islamic and international law. Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-230-60618-0.

- Marouf, Abdullah. المدخل إلى دراسة المسجد الأقصى المبارك [Introduction to the study of the Blessed Aqsa Mosque] (in Arabic) (1st 2006 ed.). دار العلم للملايين.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Al-Aqsa Mosque. |

- Noble Sanctuary: Al-Aqsa Mosque

- Timeline: Al-Aqsa Mosque, Aljazeera

- Visit Al-Aqsa Mosque

- Al-Shindagah

- Al-Masjid al-Haram and al-Masjid al-Aqsa as the First and Second Mosques on Earth