Medina

Medina ٱلْمَدِيْنَة ٱلْمُنَوَّرَة Al-Madīnah al-Munawwarah مَدِيْنَة ٱلنَّبِي Madīnat an-Nabī يَثْرِب Yathrib | |

|---|---|

| The Prophet's City | |

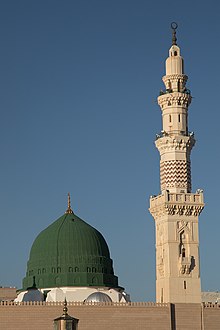

Clockwise from top left: Al-Masjid an-Nabawi interior, Al-Masjid an-Nabawi, Medina skyline, Quba Mosque, Mount Uhud | |

| Coordinates: 24°28′N 39°36′E / 24.467°N 39.600°ECoordinates: 24°28′N 39°36′E / 24.467°N 39.600°E | |

| Country | |

| Region | Al Madinah |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Khalid Taher |

| • Regional Governor | Faisal bin Salman bin Abdulaziz Al Saud |

| Area | |

| • City | 589 km2 (227 sq mi) |

| • Urban | 293 km2 (113 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 620 m (2,030 ft) |

| Population (2010) | |

| • City | 1,183,205 |

| • Density | 2,000/km2 (5,200/sq mi) |

| • Urban | 785,204 |

| Time zone | UTC+3 (Arabia Standard Time) |

| Website | https://www.saudi.gov.sa |

Medina[a], also transliterated as Madīnah (Hejazi pronunciation: [almaˈdiːna]), is the capital of the Al-Madinah Region in Saudi Arabia. At the city's heart is al-Masjid an-Nabawi ('The Prophet's Mosque'), which is the burial place of the Islamic prophet, Muhammad. Medina is one of the three holiest cities in Islam, the other two being Mecca and Jerusalem.

Medina was Muhammad's destination in his Hijrah (migration) from Mecca, and became the capital of a rapidly increasing Muslim Empire, under Muhammad's leadership, serving as the power base of Islam, and where Muhammad's Ummah (Community), composed of both locals and immigrants from Muhammad's original home of Mecca, developed. Medina is home to three prominent mosques, namely al-Masjid an-Nabawi,[1] Quba Mosque, and Masjid al-Qiblatayn ('The mosque of the two Qiblas'). Muslims believe that the chronologically final surahs of the Quran were revealed to Muhammad in Medina, and are called Medinan surahs in contrast to the earlier Meccan surahs.[2][3]

Etymology[edit]

The Arabic word al-Madīnah (ٱلْمَدِيْنَة) simply means 'the city'. Before the advent of Islam, the city was known as Yathrib (pronounced [ˈjaθrib]; يَثْرِب). The word Yathrib has been recorded in Surat al-Ahzab of the Quran.[Quran 33:13]

The city has also been called Taybah (Good) ([ˈtˤajba]; طَيْبَة) and Tabah (Arabic: طَابَة similar in meaning to the former).[citation needed] An alternative[clarification needed] name is al-Madīnah an-Nabawiyyah (ٱلْمَدِيْنَة ٱلنَّبَوِيَّة) or Madīnat an-Nabī (مَدِيْنَة ٱلنَّبِي, "City of the Prophet").

Overview[edit]

As of 2010[update], the city of Medina has a population of 1,183,205.[4]. Later the city's name was changed to Madīna-tu n-Nabī or al-Madīnatu 'l-Munawwarah (ٱلْمَدِيْنَة ٱلْمُنَوَّرَة, "the lighted city" or "the radiant city"). Medina is celebrated for containing al-Masjid an-Nabawi and as the city which gave refuge to him and his followers, and so ranks as the second holiest city of Islam, after Mecca.[5] Muhammad was buried in Medina, under the Green Dome, as were the first two Rashidun caliphs, Abu Bakr and Umar, who were buried next to him in what used to be Muhammad's house.

Medina is 210 miles (340 km) north of Mecca and about 120 miles (190 km) from the Red Sea coast. It is situated in the most fertile part of all the Hejazi territory, the streams of the vicinity tending to converge in this locality. An immense plain extends to the south; in every direction the view is bounded by hills and mountains.

The historic city formed an oval, surrounded by a strong wall, 30 to 40 feet (9.1 to 12.2 m) high, dating from the 12th century CE, and was flanked with towers, while on a rock, stood a castle. Of its four gates, the Bab-al-Salam, or Egyptian gate, was remarkable for its beauty. Beyond the walls of the city, west and south were suburbs consisting of low houses, yards, gardens and plantations. These suburbs also had walls and gates. Almost all of the historic city has been demolished in the Saudi era. The rebuilt city is centred on the vastly expanded al-Masjid an-Nabawi.

The graves of Fatimah (Muhammad's daughter) and Hasan (Muhammad's grandson), across from the mosque at Jannat al-Baqi', and Abu Bakr (first caliph and the father of Muhammad's wife, Aisha), and of Umar ibn Al-Khattab), the second caliph, are also here. The mosque dates back to the time of Muhammad, but has been twice reconstructed.[6]

Because of the Saudi government's religious policy and concern that historic sites could become the focus for idolatry, much of Medina's Islamic physical heritage has been destroyed.

Religious significance in Islam[edit]

Medina's importance as a religious site derives from the presence of al-Masjid an-Nabawi. The mosque was expanded by the Umayyad Caliph Al-Walid I. Mount Uhud is a mountain north of Medina which was the site of the second battle between Muslim and Meccan forces.

After Muhammad migrated to Madinah, he built Quba' Mosque and offered prayers in it. He would ride a camel or walk to the mosque every Saturday to offer 2 rakaats of prayers.[7] Quba' Mosque is now located in the metropolitan area of Medina. It was destroyed by lightning, probably about 850 CE, and the graves were almost forgotten. In 892, the place was cleared up, the graves located and a fine mosque built, which was destroyed by fire in 1257 CE and almost immediately rebuilt. It was restored by Qaitbay, the Egyptian ruler, in 1487.[6]

Muslims are encouraged to perform 2 rakaat of Sunnah prayer at this Quba' Mosque. According to a hadith from Sunan Ibn Majah, Sahl ibn Hunayf reported that Muhammad said, “Whoever purifies himself in his house, then comes to the mosque of Quba' and prays in it, he will have a reward like the Umrah pilgrimage.” (Hadith by Imam Ibn Majah)[8]

Masjid al-Qiblatain is another mosque also historically important to Muslims. It is where the command was sent to Muhammad to change the direction of prayer (qibla) from Jerusalem to Mecca, according to a hadith.[9] At the prayer hall, you would be able to see signs showing the direction of Makkah as well as Jerusalem. The mosque is currently being expanded to be able to hold more than 4,000 worshippers.[10]

Like Mecca, the city of Medina only permits Muslims to enter, although the haram (area closed to non-Muslims) of Medina is much smaller than that of Mecca, with the result that many facilities on the outskirts of Medina are open to non-Muslims, whereas in Mecca the area closed to non-Muslims extends well beyond the limits of the built-up area. Both cities' numerous mosques are the destination for large numbers of Muslims on their 'Umrah (second pilgrimage after Hajj). Hundreds of thousands of Muslims come to Medina annually while performing pilgrimage Hajj. Al-Baqi' is a significant cemetery in Medina where several family members of Muhammad, caliphs and scholars are buried.

Islamic scriptures emphasise the sacredness of Medina. Medina is mentioned several times as being sacred in the Quran, for example ayah; 9:101, 9:129, 59:9, and ayah 63:7. Medinan suras are typically longer than their Meccan counterparts. There is also a book within the hadith of Bukhari titled 'Virtues of Medina'.[11]

Sahih Bukhari says:

Narrated Anas: The Prophet said, "Medina is a sanctuary from that place to that. Its trees should not be cut and no heresy should be innovated nor any sin should be committed in it, and whoever innovates in it an heresy or commits sins (bad deeds), then he will incur the curse of God, the angels, and all the people."

History[edit]

Pre-7th century[edit]

By the fourth century, Arab tribes began to encroach from Yemen, and there were three prominent Jewish tribes that inhabited the city into the 7th century CE: the Banu Qaynuqa, the Banu Qurayza, and Banu Nadir.[12] Ibn Khordadbeh later reported that during the Persian Empire's domination in Hejaz, the Banu Qurayza served as tax collectors for the Persian Shah.[13]

The situation changed after the arrival from Yemen of two new Arab tribes named Banu Aus (or Banu 'Aws) and Banu Khazraj. At first, these tribes were allied with Jewish rulers, but later they revolted and became independent.[14] Toward the end of the 5th century,[15] the Jewish rulers lost control of the city to Banu Aus and Banu Khazraj. The Jewish Encyclopedia states that "by calling in outside assistance and treacherously massacring at a banquet the principal Jews", Banu Aus and Banu Khazraj finally gained the upper hand at Medina.[12]

Most modern historians accept the claim of the Muslim sources that after the revolt, the Jewish tribes became clients of the Aus and the Khazraj.[16] However, according to scholar of Islam William Montgomery Watt, the clientship of the Jewish tribes is not borne out by the historical accounts of the period prior to 627, and he maintained that the Jewish populace retained a measure of political independence.[14]

Early Muslim chronicler Ibn Ishaq tells of an ancient conflict between the last Yemenite king of the Himyarite Kingdom[17] and the residents of Yathrib. When the king was passing by the oasis, the residents killed his son, and the Yemenite ruler threatened to exterminate the people and cut down the palms. According to Ibn Ishaq, he was stopped from doing so by two rabbis from the Banu Qurayza tribe, who implored the king to spare the oasis because it was the place "to which a prophet of the Quraysh would migrate in time to come, and it would be his home and resting-place." The Yemenite king thus did not destroy the town and converted to Judaism. He took the rabbis with him, and in Mecca, they reportedly recognised the Ka'bah as a temple built by Abraham and advised the king "to do what the people of Mecca did: to circumambulate the temple, to venerate and honour it, to shave his head and to behave with all humility until he had left its precincts." On approaching Yemen, tells ibn Ishaq, the rabbis demonstrated to the local people a miracle by coming out of a fire unscathed and the Yemenites accepted Judaism.[18]

Eventually the Banu Aus and the Banu Khazraj became hostile to each other and by the time of Muhammad's Hijra (emigration) to Medina in 622 CE/1 AH, they had been fighting for 120 years and were the sworn enemies of each other.[19] The Banu Nadir and the Banu Qurayza were allied with the Aus, while the Banu Qaynuqa sided with the Khazraj.[20] They fought a total of four wars.[14]

Their last and bloodiest battle was the Battle of Bu'ath[14] that was fought a few years before the arrival of Muhammad.[12] The outcome of the battle was inconclusive, and the feud continued. Abd-Allah ibn Ubayy, one Khazraj chief, had refused to take part in the battle, which earned him a reputation for equity and peacefulness. Until the arrival of Muhammad, he was the most respected inhabitant of Yathrib. To solve the ongoing feud, concerned residents of the city met secretly with Muhammad in Al-Aqaba, a place between Makkah and Mina, inviting him and his small group of believers to come to Yathrib, where Muhammad could serve as disinterested mediator between the factions and his community could practice its faith freely.

Muhammad's arrival[edit]

In 622 CE/1 AH, Muhammad and around 70 Meccan Muhajirun believers left Mecca for sanctuary in Yathrib, an event that transformed the religious and political landscape of the city completely; the longstanding enmity between the Aus and Khazraj tribes was dampened as many of the two Arab tribes and some local Jews embraced Islam. Muhammad, linked to the Khazraj through his great-grandmother, was agreed on as civic leader. The Muslim converts native to Yathrib of whatever background—pagan Arab or Jewish—were called Ansar ("the Patrons" or "the Helpers"), while the Muslims would pay the Zakat tax.

According to Ibn Ishaq, the local pagan Arab tribes, the Muslim Muhajirun from Mecca, the local Muslims (Ansar), and the Jewish population of the area signed an agreement, the Constitution of Medina, which committed all parties to mutual co-operation under the leadership of Muhammad. The nature of this document as recorded by Ibn Ishaq and transmitted by Ibn Hisham is the subject of dispute among modern Western historians, many of whom maintain that this "treaty" is possibly a collage of different agreements, oral rather than written, of different dates, and that it is not clear exactly when they were made. Other scholars, however, both Western and Muslim, argue that the text of the agreement—whether a single document originally or several—is possibly one of the oldest Islamic texts we possess.[21] In Yemenite Jewish sources, another treaty was drafted between Muhammad and his Jewish subjects, known as kitāb ḏimmat al-nabi, written in the 17th year of the Hijra (638 CE), and which gave express liberty unto Jews living in Arabia to observe the Sabbath and to grow-out their side-locks, but were required to pay the jizya (poll-tax) annually for their protection by their patrons.[22]

Battle of Badr[edit]

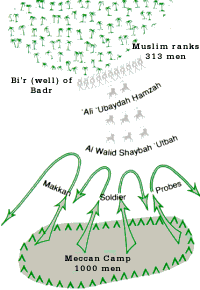

The Battle of Badr was a key battle in the early days of Islam and a turning point in Muhammad's struggle with his opponents among the Quraysh in Mecca. In the spring of 624, Muhammad received word from his intelligence sources that a trade caravan, commanded by Abu Sufyan ibn Harb, Chieftain of the Meccan Quraysh, and guarded by thirty to forty men, was travelling from Syria back to Mecca. Muhammad gathered an army of 313 men, the largest army the Muslims had put in the field yet. However, many early Muslim sources, including the Quran, indicate that no serious fighting was expected,[23] and the future Caliph Uthman ibn Affan stayed behind to care for his sick wife.

As the caravan approached Medina, Abu Sufyan began hearing from travellers and riders about Muhammad's planned ambush. He sent a messenger named Damdam to Mecca to warn the Quraysh and get reinforcements. Alarmed, the Quraysh assembled an army of 900–1,000 men to rescue the caravan. Many of the Qurayshi nobles, including Amr ibn Hishām, Walid ibn Utba, Shaiba, and Umayyah ibn Khalaf, joined the army. However, some of the army was to later return to Mecca before the battle.

The battle started with champions from both armies emerging to engage in combat. The Muslims sent out Ali, Ubaydah ibn al-Harith (Obeida), and Hamza ibn ‘Abd al-Muttalib. The Muslims dispatched the Meccan champions in a three-on-three mêlée, Hamzah killed his opponent with the very first strike, although Ubaydah was mortally wounded.[24]

Now both armies began firing arrows at each other. Two Muslims and an unknown number of Quraysh were killed. Before the battle started, Muhammad had given orders for the Muslims to attack with their ranged weapons, and only engage the Quraysh with melee weapons when they advanced.[25] Now he gave the order to charge, throwing a handful of pebbles at the Meccans in what was probably a traditional Arabian gesture while yelling "Defaced be those faces!"[26][27] The Muslim army yelled "Yā manṣūr amit!"[28] and rushed the Qurayshi lines. The Meccans, although substantially outnumbering the Muslims, promptly broke and ran. The battle itself only lasted a few hours and was over by the early afternoon.[26] The Quran describes the force of the Muslim attack in many verses, which refer to thousands of angels descending from Heaven at Badr to slaughter the Quraysh.[27][29] Early Muslim sources take this account literally, and there are several hadith where Muhammad discusses the Angel Jibreel and the role he played in the battle.

Ubaydah ibn al-Harith (Obeida) was given the honour of "he who shot the first arrow for Islam" as Abu Sufyan altered course to flee the attack. In retaliation for this attack Abu Sufyan requested an armed force from Mecca.[30]

Throughout the winter and spring of 623 other raiding parties were sent by Muhammad from Medina.

Battle of Uhud[edit]

In 625, Abu Sufyan, who paid tax to the Byzantine empire regularly, once again led a Meccan force against Medina. Muhammad marched out to meet the force but before reaching the battle, about one third of the troops under Abd-Allah ibn Ubayy withdrew. With a smaller force, the Muslim army had to find a strategy to gain the upper hand. A group of archers were ordered to stay on a hill to keep an eye on the Meccan's cavalry forces and to provide protection at the rear of the Muslim's army. As the battle heated up, the Meccans were forced to somewhat retreat. The battle front was pushed further and further away from the archers, whom, from the start of the battle, had really nothing to do but watch. In their growing impatience to be part of the battle, and seeing that they were somewhat gaining advantage over the Kafirun (Infidels) these archers decided to leave their posts to pursue the retreating Meccans. A small party, however, stayed behind; pleading all along to the rest to not disobey their commanders' orders. But their words were lost among the enthusiastic yodels of their comrades.

However, the Meccans' retreat was actually a manufactured manoeuvre that paid off. The hillside position had been a great advantage to the Muslim forces, and they had to be lured off their posts for the Meccans to turn the table over. Seeing that their strategy had actually worked, the Meccans cavalry forces went around the hill and re-appeared behind the pursuing archers. Thus, ambushed in the plain between the hill and the front line, the archers were systematically slaughtered, watched upon by their desperate comrades who stayed behind up in the hill, shooting arrows to thwart the raiders, but to little effect.

However, the Meccans did not capitalise on their advantage by invading Medina and returned to Mecca. The Medinans suffered heavy losses, and Muhammad was injured.[32]

Battle of the Trench[edit]

In 627, Abu Sufyan once more led Meccan forces against Medina. Because the people of Medina had dug a trench to further protect the city, this event became known as the Battle of the Trench. After a protracted siege and various skirmishes, the Meccans withdrew again. During the siege, Abu Sufyan had contacted the remaining Jewish tribe of Banu Qurayza and formed an agreement with them, to attack the defenders from behind the lines. It was however discovered by the Muslims and thwarted. This was in breach of the Constitution of Medina and after the Meccan withdrawal, Muhammad immediately marched against the Qurayza and laid siege to their strongholds. The Jewish forces eventually surrendered. Some members of the Banu Aus now interceded on behalf of their old allies and Muhammad agreed to the appointment of one of their chiefs, Sa'd ibn Mua'dh, as judge. Sa'ad judged by Jewish Law that all male members of the tribe should be killed and the women and children enslaved as was the law stated in the Old Testament for treason (Deutoronomy).[33] This action was conceived of as a defensive measure to ensure that the Muslim community could be confident of its continued survival in Medina. The historian Robert Mantran argues that from this point of view it was successful — from this point on, the Muslims were no longer primarily concerned with survival but with expansion and conquest.[33]

Capital city of Muhammad and the Rashidun Caliphate[edit]

.

In the ten years following the hijra, Medina formed the base from which Muhammad and the Muslim army attacked and were attacked, and it was from here that he marched on Mecca, entering it without battle in 629 CE/8 AH, all parties acquiescing to his leadership. Afterwards, however, despite Muhammad's tribal connection to Mecca and the ongoing importance of the Meccan Ka'bah for Islamic pilgrimage (Hajj), Muhammad returned to Medina, which remained for some years the most important city of Islam and the capital of the early caliphate.

Yathrib was renamed Medina from Madinat al-Nabi ("city of the Prophet" in Arabic) in honour of Muhammad's prophethood and death there. (Alternatively, Lucien Gubbay suggests the name Medina could also have been a derivative from the Aramaic word Medinta, which the Jewish inhabitants could have used for the city.[35])

Under the first three caliphs Abu Bakr, Umar, and Uthman, Medina was the capital of a rapidly increasing Muslim Empire. During the period of Uthman, the third caliph, a party of Arabs from Egypt, disgruntled at his political decisions, attacked Medina in 656 CE/35 AH and murdered him in his own home. Ali, the fourth caliph, changed the capital of the caliphate from Medina to Kufa in Iraq. After that, Medina's importance dwindled, becoming more a place of religious importance than of political power.

In 1256 CE Medina was threatened by a lava flow from the Harrat Rahat volcanic area.[36][37]

After the fragmentation of the caliphate, the city became subject to various rulers, including the Mamluks of Cairo in the 13th century and finally, in 1517, the Ottoman Empire.[38]

World War I to Saudi control[edit]

In the beginning of the 20th century, during World War I, Medina witnessed one of the longest sieges in history. Medina was a city of the Turkish Ottoman Empire. Local rule was in the hands of the Hashemite clan as Sharifs or Emirs of Mecca. Fakhri Pasha was the Ottoman governor of Medina. Ali bin Hussein, the Sharif of Mecca and leader of the Hashemite clan, revolted against the Caliph in Constantinople (Istanbul) and sided with Great Britain. The city of Medina was besieged by the Sharif's forces, and Fakhri Pasha tenaciously held on during the Siege of Medina from 1916 till 10 January 1919. He refused to surrender and held on another 72 days after the Armistice of Moudros, until he was arrested by his own men.[39] In anticipation of the plunder and destruction to follow, Fakhri Pasha secretly sent the Sacred Relics of Medina to Istanbul.[40]

As of 1920, the British described Medina as "much more self-supporting than Mecca."[41] After the First World War, the Hashemite Sayyid Hussein bin Ali was proclaimed King of an independent Hejaz. Soon after, in 1924, he was defeated by Ibn Saud, who integrated Medina and the whole of the Hejaz into the modern kingdom of Saudi Arabia.

Modern Medina[edit]

Today, Medina ("Madinah" officially), in addition to being the second most important Islamic pilgrimage destination after Mecca, is an important regional capital of the western Saudi Arabian province of Al Madinah. Though the city's sacred core of the old city is off limits to non-Muslims, Medina is inhabited by an increasing number of Muslim and non-Muslim expatriate workers of other Arab nationalities (Egyptians, Jordanians, Lebanese, etc.), South Asians (Bangladeshis, Indians, Pakistanis, etc.) and Filipinos.

Geography[edit]

Medina is located in the Hijaz Region north-western of the country, 250 kilometres (160 miles) east to the Red Sea , and 620 metres (2,030 feet) above sea level. It lies at the meeting-point of longitude 39º36' east and latitude 24º28' north. It covers an area of about 50 square kilometres (19 square miles).

Topography[edit]

Medina is a desert oasis surrounded by mountains and volcanic hills, as mentioned in several references and sources. It was known as Yathrib in Writings of ancient Maeniand, this is obvious evidence that the population structure of this desert oasis is a combination of north Arabs and South Arabs, who settled there and built their civilization during the thousand years before Christ.

The soil surrounding Medina consists of mostly basalt, while the hills, especially noticeable to the south of the city, are volcanic ash which dates to the first geological period of the Paleozoic Era. It is surrounded by a number of mountains: Al-Hujaj, or Pilgrims' Mountain to the west, Salaa to the north-west, Al-E'er or Caravan Mountain to the south and Uhad to the north. The city is situated on a flat mountain plateau at the junction of the three valleys of Al-Aql, Al-Aqiq, and Al-Himdh, for this reason, there are large green areas amidst a dry mountainous region. Its western and southwestern parts have many volcanic rocks.

Climate[edit]

Medina has a hot desert climate (Köppen climate classification BWh). Summers are extremely hot with daytime temperatures averaging about 43 °C (109 °F) with nights about 29 °C (84 °F). Temperatures above 45 °C (113 °F) are not unusual between June and September. Winters are milder, with temperatures from 12 °C (54 °F) at night to 25 °C (77 °F) in the day. There is very little rainfall, which falls almost entirely between November and May.

| Climate data for Medina (1985–2010) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 33.2 (91.8) |

36.6 (97.9) |

40.0 (104.0) |

43.0 (109.4) |

46.0 (114.8) |

47.0 (116.6) |

49.0 (120.2) |

48.4 (119.1) |

46.4 (115.5) |

42.8 (109.0) |

36.8 (98.2) |

32.2 (90.0) |

49.0 (120.2) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 24.2 (75.6) |

26.6 (79.9) |

30.6 (87.1) |

34.3 (93.7) |

39.6 (103.3) |

42.9 (109.2) |

42.9 (109.2) |

43.5 (110.3) |

42.3 (108.1) |

36.3 (97.3) |

30.6 (87.1) |

26.0 (78.8) |

35.2 (95.4) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 17.9 (64.2) |

20.2 (68.4) |

23.9 (75.0) |

28.5 (83.3) |

33.0 (91.4) |

36.3 (97.3) |

36.5 (97.7) |

37.1 (98.8) |

35.6 (96.1) |

30.4 (86.7) |

24.2 (75.6) |

19.8 (67.6) |

28.6 (83.5) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 11.6 (52.9) |

13.4 (56.1) |

16.8 (62.2) |

21.2 (70.2) |

25.5 (77.9) |

28.4 (83.1) |

29.1 (84.4) |

29.9 (85.8) |

27.9 (82.2) |

21.9 (71.4) |

17.7 (63.9) |

13.5 (56.3) |

21.5 (70.7) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 1.0 (33.8) |

3.0 (37.4) |

7.0 (44.6) |

11.5 (52.7) |

14.0 (57.2) |

21.7 (71.1) |

22.0 (71.6) |

23.0 (73.4) |

18.2 (64.8) |

11.6 (52.9) |

9.0 (48.2) |

3.0 (37.4) |

1.0 (33.8) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 6.3 (0.25) |

3.1 (0.12) |

9.8 (0.39) |

9.6 (0.38) |

5.1 (0.20) |

0.1 (0.00) |

1.1 (0.04) |

4.0 (0.16) |

0.4 (0.02) |

2.5 (0.10) |

10.4 (0.41) |

7.8 (0.31) |

60.2 (2.37) |

| Average rainy days | 2.6 | 1.4 | 3.2 | 4.1 | 2.9 | 0.1 | 0.4 | 1.5 | 0.6 | 2.0 | 3.3 | 2.5 | 24.6 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 38 | 31 | 25 | 22 | 17 | 12 | 14 | 16 | 14 | 19 | 32 | 38 | 23 |

| Source: Jeddah Regional Climate Center[42] | |||||||||||||

Demographics[edit]

As of 2018, the recorded population was 2,188,138[44], with an annual increase of 50,800 people which represents a growth rate of 2.32%.[45] Being a destination of Muslims from around the world, Medina witnesses illegal stay of visitors after performing Hajj or Umrah, despite the strict rules the government apply. However, The head of Central Hajj Committee Prince Khalid Al-Faisal stated in 2018 that the numbers of illegal staying visitors have dropped by 29%.[46]

Religion[edit]

As with most cities in Saudi Arabia, Islam is the religion adhered by the majority of the population of Medina. Sunnis of different schools (Hanafi, Maliki, Shafi'i and Hanbali) constitute the majority, while there is a significant Shia minority in and around Medina, such as the Nakhawila. Outside the city center (reserved for Muslims only), there are significant numbers of non-Muslim migrant workers and expats.

Economy[edit]

Historically, Medina is known for growing dates. As of 1920, 139 varieties of dates were being grown in the area.[47] Medina also was known for growing many types of vegetables.[48]

Medina has two industrial areas, the biggest was established in 2003 with a total area of 10,000,000 m², and managed by Modon. It is located 50 km from Prince Mohammed bin Abdulaziz International Airport, and 200 km from Yanbu Commercial Port, and has 236 factories, which produces petroleum products, building materials, food products, and many other products.[49]

The Knowledge Economic City (KEC) is a Saudi Arabian joint stock company founded in 2010. It focuses on real estate development and knowledge-based industries.[50] The project is under development and is expected to highly increase the number of jobs in Medina by its finish.[51]

Religious tourism plays a major part in Medina's economy, being the second holiest city in Islam, and holding many historical Islamic locations and Al-Masjid Al-Nabawi, it attracts more than 7 million annual visitors who come to perform Hajj during the Hajj season, and Umrah throughout the year.[52]

Education[edit]

Higher Education[edit]

Taibah University is a public university providing higher education for the residents of Madinah Region,it has 28 colleges 16 of which are in Medina. It offers 89 academic programs and enrolls about 69210 students of both males and females.[53]

The Islamic University, established in 1961, is the oldest higher education institution in the region, with around 22000 students enrolled. It offers majors in Sharia, Qur'an, Usul al-din, Hadith, and Arabic.[54] The university offers Bachelor of Arts degrees and also Master's and Doctorate Degrees.[55] Studies at the College of Sharia Islamic law were the first to start when the university opened. The admission is open to Muslims based on scholarships programs that provide accommodation and living expenses. The university also provides an Arabic Language for Non-Native speaker Institute for those who do not have a basic level of Arabic.[56], In 2012, the university expanded its programs by establishing the college of science, which offers Engineering and Computer Science majors.[57]

Al-Madinah College of Technology, which is governed by TVTC, offers a variety of degree programs including electrical technology, mechanical technology, computer technology and electronic technology.[58]

Private universities include University of Prince Mugrin, Arab Open University, and Al-Rayan Colleges.

Primary and Secondary Education[edit]

The General Administration of Education is the governing body of education in Madinah Region, it operates 724 public schools for males and 773 for females in Madinah Region.[59].

Taibah High School is one of the most notable schools in Saudi Arabia, it was established in 1942, and was the second largest school in the country at that time. Many Saudi ministers and government officials have graduated from this high school, which gives it a reputation of excellence and a historical importance.[60].

Transport[edit]

Air[edit]

Medina is served by Prince Mohammad bin Abdulaziz International Airport (IATA: MED, ICAO: OEMA), located about 15 kilometres (9.3 miles) from the city centre. It handles domestic flights, while it has scheduled international services to regional destinations. It is the fourth busiest airport in Saudi Arabia, handling 8,144,790 passengers in 2018.[61]

The airport project was announced as the world's best by Engineering News-Record's 3rd Annual Global Best Projects Competition held on September 10, 2015.[62][63] The airport also received the first Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) Gold certificate in the MENA region.[64]

Medina Airport and Jeddah Airport are the only flight portals for pilgrims during Hajj season.

High Speed Rail[edit]

The Haramain High Speed Railway (HHR) came into operation in 2018, linking Medina with Mecca, and passes through three stations: Jeddah, King Abdul Aziz International Airport, and King Abdullah Economic City.[65]. It runs along 444 kilometres (276 miles) with a speed of 300 km/h, and has an annual capacity of 60 million passengers.[66]

In 2015, the MMDA announced a three-line metro project in extension to the public transportation master plan in Medina.[67]

Roads[edit]

Two major highways connects Medina to the rest of the country. Highway 15 runs north through Khaybar to Tabuk, and south through Jeddah, Mecca, Abha, to Najran. Highway 60, runs east through Buraidah to Riyadh, and west through Badr to Yanbu.

The city is served by three ring roads, the inner is King Faisal Road, a 5 km ring road that surrounds Al-Masjid an-Nabawi and the downtown area, the middle ring road is King Abdullah Road which is a 27 km road that surrounds most of Medina, King Khalid Road is the biggest ring road that surrounds the whole city with 60 km of roads.

Bus System[edit]

The bus transport system in Medina was established in 2012 by the Al-Madinah Region Development Authority (MMDA) and operated by SAPTCO. The newly established bus system includes 10 lines connects different regions of the city to Al-Masjid Al-Nabawi and the downtown area, and serves around 20,000 passengers on a daily basis.[68][69]

In 2017, the MMDA launched Medina City Sightseeing Bus Service. Open top buses takes passengers sightseeing through two lines to 11 destinations, including Al-Masjid Al-Nabawi, and offers audio tour guidance with 8 different languages.[70]

By the end of 2019, the MMDA announced its plan to expand the bus network with 15 BRT lines, in extension to the public transportation master plan in Medina. The project was set to be done in 2023.[71]

Culture[edit]

Landmarks[edit]

Al-Masjid Al-Nabawi (the prophet's mosque), is the main destination in Medina, Muslim visitors from all over the world comes to pray at the mosque, and visit the Tomb of Muhammad, and visit Al-Baqi' cemetery, where Fatimah the daughter of Muhammed, Al-Hasan the grandson of Muhammed, and many of the companions of Muhammed are buried.

Quba Mosque which is the first mosque built in Islam, is also a main destination for the visitors of Medina. In 2015, the MMDA announced Darb Al-Sunnah (Sunnah Path) Project, which aims to develop and transform Quba Road ( a 3km road connecting Al-Masjid Al-Nabawi to Quba Mosque) to an avenue, paving the whole road for pedestrians, and providing service facilities to the visitors. The project also aims to revive the Sunnah where Muhammed used to walk from his house (Al-Masjid Al-Nabawi) to quba mosque every Saturday afternoon. [72] The project was said to include 5 plazas, museums, multiple hotels and shopping cen ters. [73] In 2018 the MMDA opened Quba Square to the public, as the first phase of Darb Al-Sunnah project, and hosted a festival in during the month of Ramadn in the same year. It was reported that more than 500,000 visitors attended the festival.[74]

Masjid al-Qiblatayn where Muhammad received the command to change the Qiblah (Direction of Prayer) from Jerusalem to Mecca.

Mount Uhud is a mountain located north of Medina that stands 1,077 m (3,533 ft) high. Shuhada'a Uhud square, is the location of the Battle of Uhud, the square includes the archers mountain, the cemetery of Shuhadaa Uhud, and the mosque of shuhada uhud which was built in 2017.[75]

King Fahd Complex for the Printing of the Holy Quran, established in 1985, the complex is the biggest publisher of Quran in the world, it employs around 1100 people[76], and publishes 361 different publications in many languages. It is reported that more than 400,000 people from around the world visits the complex every year.[77]

Museums[edit]

Al-Madinah Museum: It exhibits Al-Madina heritage and history featuring different archaeological collections, visual galleries and rare images that related to Al-Medina.[78] It is also includes the Hejaz Railway Museum.

Dar Al Madinah Museum: Opened in 2011, the museum covers the history of Madinah specializing in the architectural and urban heritage of the city.[79]

Holy Quran Exhibition: Situated right next to the Prophet's mosque in Madinah, the exhibition houses rare manuscripts of the Quran. [80]

Arts[edit]

Medina Arts Center, founded in 2018 and operated by the MMDA's Cultural Program, focuses on modern and contemporary arts. The center aims to enhance arts and enrich the artistic and cultural movement of the society, and empowering artists of all groups and ages. As of February 2020, it held more than 13 group and solo art galleries, and holds weekly workshops and discussions. The center is located in King Fahd Park on the south-west side of the Quba Mosque on an area of 8,200 m².[81]

Dar Al-Qalam Center for Arabic Calligraphy, is a center dedicated to the art of Arabic Calligraphy. It is located north-west to Al-Masjid Al-Nabawi, just across from Hejaz Railway Museum. In 2018, the MMDA launched Madinah Forum of Arabic Calligraphy, an annual forum to celebrate Arabic calligraphy, and renowned Arabic calligraphers. The event included discussions about Arabic calligraphy, and a gallery to show the work of 50 Arabic calligraphers from 10 countries. [82]In April 2020, it was announced that the center was to be renamed to "Prince Mohammed bin Salman Center for Arabic Calligraphy", and to be an international hub for Arabic Calligraphers, in conjunction with the "Year of Arabic Calligraphy" event that is organized by the Ministry of Culture during the years 2020 and 2021.[83]

Madinah Forum of Live Sculpture, was launched in 2018 by the MMDA's cultural program. It was held in Quba Square for 20 days, with the participation of 16 sculptors from 11 countries. The forum aimed to celebrate sculpture as it is an ancient art, and to attract young artists to this form of art.[84]

Sports[edit]

Medina is the home of two sports clubs Al-Ansar FC, and Ohod FC, they both play their home games at Prince Mohammed bin Abdulaziz Stadium.

Accent[edit]

Being located in the Hejaz Region; Medina is one of the cities distinguished by the Hejazi accent, which is among the most recognizable accents within the Arabic language.

Destruction of heritage[edit]

Saudi Arabia is hostile to any reverence given to historical or religious places of significance for fear that it may give rise to shirk (idolatry). As a consequence, under Saudi rule, Medina has suffered from considerable destruction of its physical heritage including the loss of many buildings over a thousand years old.[85] Critics have described this as "Saudi vandalism" and claim that in Medina and Mecca over the last 50 years, 300 historic sites linked to Muhammad, his family or companions have been lost.[86] In Medina, examples of historic sites which have been destroyed include three of the Seven Mosques, the Raj'at ash-Shams Mosque.[87]

See also[edit]

- Haramain High Speed Rail Project

- Jeddah

- Nakhawila

- Siege of Medina

- List of expeditions of Muhammad in Medina

References[edit]

- ^ /məˈdiːnə/; Arabic: ٱلْمَدِيْنَة ٱلْمُنَوَّرَة, al-Madīnah al-Munawwarah, "the radiant city"; or ٱلْمَدِيْنَة, al-Madīnah (Hejazi pronunciation: [almaˈdiːna]), "the city"

- ^ "Masjid Quba' – Hajj". Saudi Arabia: Hajinformation.com. Retrieved 26 March 2013.

- ^ Historical value of the Qur'ân and the Ḥadith A.M. Khan

- ^ What Everyone Should Know About the Qur'an Ahmed Al-Laithy

- ^ "The population of Medina 2016" (PDF).

- ^ However, an article in Aramco World[dead link] by John Anthony states: "To the perhaps parochial Muslims of North Africa in fact the sanctity of Kairouan is second only to Mecca among all cities of the world." Saudi Aramco's bimonthly magazine's goal is to broaden knowledge of the cultures, history and geography of the Arab and Muslim worlds and their connections with the West; pages 30–36 of the January/February 1967 print edition The Fourth Holy City

- ^ a b 1954 Encyclopedia Americana, vol. 18, pp.587, 588

- ^ Moore, Cerwyn (15 January 2018), "Friday Prayers and Sermon in the Grand Mosque of Mosul", Al-Qaeda 2.0, Oxford University Press, pp. 147–152, doi:10.1093/oso/9780190856441.003.0010, ISBN 978-0-19-085644-1

- ^ "10 Places To Visit In Madinah". muslim.sg. Retrieved 10 December 2019.

- ^ "Place Pilgrims Visit During or After Performing Hajj / Umrah". Dawntravels.com. Retrieved 2 September 2014.

- ^ "10 Places To Visit In Madinah". muslim.sg. Retrieved 10 December 2019.

- ^ hadith found in 'Virtues of Madinah' of Sahih Bukhari searchtruth.com

- ^ a b c Jewish Encyclopedia Medina

- ^ Peters 193

- ^ a b c d "Al-Medina." Encyclopaedia of Islam

- ^ for date see "J. Q. R." vii. 175, note

- ^ See e.g., Peters 193; "Qurayza", Encyclopaedia Judaica

- ^ Muslim sources usually referred to Himyar kings by the dynastic title of "Tubba'".

- ^ Guillaume 7–9, Peters 49–50

- ^ Subhani, The Message: The Events of the First Year of Migration Archived 24 May 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ For alliances, see Guillaume 253

- ^ Firestone 118. For opinions disputing the early date of the Constitution of Medina, see e.g., Peters 116; "Muhammad", "Encyclopaedia of Islam"; "Kurayza, Banu", "Encyclopaedia of Islam".

- ^ Shelomo Dov Goitein, The Yemenites – History, Communal Organization, Spiritual Life (Selected Studies), editor: Menahem Ben-Sasson, Jerusalem 1983, pp. 288–299. ISBN 965-235-011-7

- ^ Sahih al-Bukhari: Volume 5, Book 59, Number 287 Archived 21 August 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Sunan Abu Dawud: Book 14, Number 2659 Archived 20 August 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Sunan Abu Dawud: Book 14, Number 2658 Archived 20 August 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Armstrong, p. 176.

- ^ a b Lings, p. 148.

- ^ "O thou whom God hath made victorious, slay!"

- ^ Quran: Al-i-Imran 3:123–125 (Yusuf Ali). "Allah had helped you at Badr, when ye were a contemptible little force; then fear Allah; thus May ye show your gratitude.§ Remember thou saidst to the Faithful: "Is it not enough for you that Allah should help you with three thousand angels (Specially) sent down?§ "Yea, – if ye remain firm, and act aright, even if the enemy should rush here on you in hot haste, your Lord would help you with five thousand angels Making a terrific onslaught.§"

- ^ The Biography of Mahomet, and Rise of Islam. Chapter Fourth. Extension of Islam and Early Converts, from the assumption by Mahomet of the prophetical office to the date of the first Emigration to Abyssinia by William Muir Archived 7 November 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Jameh Syed al-Shohada Mosque". Madain Project. Archived from the original on 6 May 2020. Retrieved 6 May 2020.

- ^ Esposito, John L. "Islam." Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices, edited by Thomas Riggs, vol. 1: Religions and Denominations, Gale, 2006, pp. 349-379.

- ^ a b Robert Mantran, L'expansion musulmane Presses Universitaires de France 1995, p. 86.

- ^ "Masjid al-Nabawi (Mosque of the Prophet)". Madain Project. Archived from the original on 6 May 2020. Retrieved 6 May 2020.

- ^ "The Jews of Arabia". dangoor.com.

- ^ "Harrat Rahat". Global Volcanism Program. Smithsonian Institution.

- ^ Bosworth,C. Edmund: Historic Cities of the Islamic World, p. 385 – "Half-a-century later, in 654/1256, Medina was threatened by a volcanic eruption. After a series of earthquakes, a stream of lava appeared, but fortunately flowed to the east of the town and then northwards."

- ^ Somel, Selcuk Aksin (13 February 2003). Historical Dictionary of the Ottoman Empire. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 9780810866065 – via Google Books.

- ^ Peters, Francis (1994). Mecca: A Literary History of the Muslim Holy Land. PP376-377. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-03267-X

- ^ Mohmed Reda Bhacker (1992). Trade and Empire in Muscat and Zanzibar: Roots of British Domination. Routledge Chapman & Hall. P63: Following the plunder of Medina in 1810 'when the Prophet's tomb was opened and its jewels and relics sold and distributed among the Wahhabi soldiery'. P122: the Ottoman Sultan Mahmud II was at last moved to act against such outrage.

- ^ Prothero, G.W. (1920). Arabia. London: H.M. Stationery Office. p. 103.

- ^ "Climate Data for Saudi Arabia". Jeddah Regional Climate Center. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 7 December 2015.

- ^ "Population in Madinah Region According to Gender and Age groups". Saudi Census. Retrieved 6 February 2020.

- ^ "Population in Madinah Region According to Gender and Age groups". Saudi Census. Retrieved 6 February 2020.

- ^ "Saudi Census Releases". Saudi Census. Retrieved 6 February 2020.

- ^ "Al-Faisal : The Number of Illegal Staying Visitors have Dropped by 29%(Arabic)". Sabq Newspaper. Retrieved 13 August 2019.

- ^ Prothero, G. W. (1920). Arabia. London: H.M. Stationery Office. p. 83.

- ^ Prothero, G. W. (1920). Arabia. London: H.M. Stationery Office. p. 86.

- ^ https://modon.gov.sa/ar/Cities/IndustrialCities/Pages/IndustrialCity.aspx?CityId=5ab5a824-f7fc-4658-8d09-b8291cf70412

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 5 February 2020. Retrieved 5 February 2020.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ Economic cities a rise Archived 24 September 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ https://haj.gov.sa/ar/InternalPageCategories/Details/49

- ^ "About Taibah University". Taibah University. Retrieved 5 February 2020.

- ^ University of Madinah Saudi Info.

- ^ University of Madinah

- ^ VibeThemes. "University of Madinah – Madinah College". Archived from the original on 5 February 2020. Retrieved 2 January 2019.

- ^ "The Islamic University Starts the Admission for Science Programs for the First Time (Arabic)". Al-Riyadh Newspaper. Retrieved 15 November 2017.

- ^ "Al-Madinah College of Technology".

- ^ "Number of Schools in Medina (Arabic)". Madinah General Administration of Education. Archived from the original on 5 February 2020. Retrieved 5 February 2020.

- ^ "History of Taibah High School (Arabic)". Al-Madina Newspaper. Retrieved 5 February 2020.

- ^ "TAV Traffic Results 2018" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 July 2019. Retrieved 6 February 2020.

- ^ "Arabian Aerospace – TAV have constructed the world's best airport".

- ^ "ENR Announces Winners of 3rd Annual Global Best Projects Competition". Retrieved 25 October 2017.

- ^ "PressReleaseDetail". Archived from the original on 30 June 2017. Retrieved 25 January 2017.

- ^ "Pictures: Saudi Arabia opens high-speed railway to public". gulfnews.com. Retrieved 9 November 2019.

- ^ "About Haramain High Speed Rail". Official Haramain High Speed Rail Website. Archived from the original on 5 February 2020. Retrieved 5 February 2020.

- ^ "MMDA Announces a 3-line Metro Project in Medina(Arabic)". Asharq Al-Awsat Newspaper.

- ^ "Madina Buses Official (Arabic)". Madina Buses Official Website.

- ^ "Medina Buses Serves 20k Passengers Daily (Arabic)". Makkah Newspaper. Retrieved 19 May 2019.

- ^ "City Sightseeing Medina". City Sightseeing Medina Official Website.

- ^ "36 Months to Create 15 Bus Lines in Medina (Arabic)". Al-Watan Newspaper. Retrieved 31 December 2019.

- ^ "Darb Al-Sunnah Project (Arabic)". Al-Madinah Newspaper. Retrieved 9 September 2015.

- ^ "Darb Al-Sunnah Project (Arabic)". Saudi Projects. Retrieved 10 February 2020.

- ^ "Quba Square, a Destination of the Visitors of Medina (Arabic)". Al-Madinah Newspaper. Retrieved 22 May 2019.

- ^ "Masjid Sayyed Al-Shuhada'a (Arabic)". Saudi Press Agency. Retrieved 26 April 2017.

- ^ "About King Fahd Complex". King Fahd Complex for the Printing of the Holy Quran. Retrieved 10 February 2020.

- ^ "Publications of King Fahd Complex (Arabic)". King Fahd Complex for the Printing of the Holy Quran. Retrieved 10 February 2020.

- ^ "Al Madinah Museum". sauditourism.sa. Archived from the original on 1 May 2019. Retrieved 21 May 2019.

- ^ Alhamdan, Shahd (23 January 2016). "Museum offers insight into history of Madinah". Saudigazette. Retrieved 9 May 2020.

- ^ "Holy Quran Exhibition | Medina, Saudi Arabia Attractions". Lonely Planet. Retrieved 9 May 2020.

- ^ "MMDA Opens Medina Arts Center (Arabic)". Al-Yaum Newspaper. Retrieved 24 February 2020.

- ^ "Madinah Forum of Arabic Calligraphy (Arabic)". Al-Madina Newspaper. Retrieved 24 February 2020.

- ^ "Prince Mohammed bin Salman Center of Arabic Calligraphy (Arabic)". Saudi Press Agency. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- ^ "16 Sculptors Participate in Madinah Forum of Live Sculpture (Arabic)". Saudi Press Agency. Retrieved 24 February 2020.

- ^ Howden, Daniel (6 August 2005). "The destruction of Mecca: Saudi hardliners are wiping out their own heritage". The Independent. Retrieved 17 January 2011.

- ^ Islamic heritage lost as Makkah modernises, Center for Islamic Pluralism

- ^ History of the Cemetery of Jannat al-Baqi retrieved 17 January 2011

Bibliography[edit]

External links[edit]

Media related to Medina at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Medina at Wikimedia Commons Media related to Category:Medina at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Category:Medina at Wikimedia Commons Medina travel guide from Wikivoyage

Medina travel guide from Wikivoyage- . New International Encyclopedia. 1905.