Oriental Orthodox Churches

| Oriental Orthodox Churches | |

|---|---|

| Type | Eastern Christian |

| Classification | Non-Chalcedonian |

| Theology | Miaphysitism |

| Polity | Episcopal |

| Structure | Communion |

| Language | Coptic, Classical Syriac, Armenian, Ge'ez, Malayalam, Koine Greek, English, Arabic and others |

| Liturgy | Alexandrian, West Syrian, Armenian and Malankara |

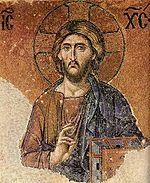

| Founder | Jesus Christ, according to Oriental Orthodox tradition |

| Separated from | Chalcedonian Christianity |

| Members | 62 million |

| Other name(s) | Oriental Orthodoxy, Old Oriental Churches, Oriental Orthodox Communion, Oriental Orthodox Church |

| Part of a series on |

| Oriental Orthodoxy |

|---|

|

| Oriental Orthodox churches |

|

Subdivisions

|

|

History and theology

|

|

Major figures

|

|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Christianity |

|---|

|

|

|

The Oriental Orthodox Churches are a group of Christian churches adhering to miaphysite Christology and theology, and together have about 62 million members worldwide.[1][2][3]

As some of the oldest religious institutions in the world, the Oriental Orthodox Churches have played a prominent role in the history and culture of Armenia, Egypt, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Sudan and parts of the Middle East and India. An Eastern Christian body of autocephalous churches, its bishops are equal by virtue of episcopal ordination, and its doctrines can be summarized in that the churches recognize the validity of only the first three ecumenical councils.[4]

The Oriental Orthodox Churches are composed of six autocephalous churches: the Coptic Orthodox Church of Alexandria, the Syriac Orthodox Church of Antioch, the Armenian Apostolic Church, the Malankara Orthodox Syrian Church (Indian Orthodox Church), the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church, and the Eritrean Orthodox Tewahedo Church.[5] Collectively, they consider themselves to be the one, holy, catholic, and apostolic Church founded by Jesus Christ in his Great Commission, and that its bishops are the successors of Christ's apostles. Most member churches are part of the World Council of Churches. Three very different rites are practiced among the churches: the western-influenced Armenian Rite, the West Syrian Rite of the Syriac Church and Malankara (Indian) Church, and the Alexandrian Rite of the Copts, Ethiopians and Eritreans.

Oriental Orthodox Churches shared communion with the Catholic Church and the Eastern Orthodox Church in the Imperial Roman Church before the Council of Chalcedon in AD 451, as well as with the Church of the East until the Council of Ephesus in AD 431, all separating primarily over differences in Christology.

The majority of Oriental Orthodox Christians live in Egypt, Ethiopia, Eritrea, India and Armenia, with smaller Syriac communities living in the Middle East—decreasing due to persecution. There are also many in other parts of the world, formed through diaspora, conversions, and missionary activity.

Name and characteristics[edit]

The name "Oriental Orthodox Churches" was coined for the Conference of Addis Ababa in 1965. At the time there were five participating churches, the Eritrean church not yet being autocephalous.[6]

Other names by which the churches have been known include Old Oriental, Ancient Oriental, Lesser Eastern, Anti-Chalcedonian, Non-Chalcedonian, Pre-Chalcedonian, Miaphysite or Monophysite,[7] although the Church of the East is equally anti-, non- and pre-Chalcedonian.[6]

The Oriental Orthodox Churches are distinguished by their recognition of only the first three ecumenical councils during the period of the State Church of the Roman Empire—the First Council of Nicaea in 325, the First Council of Constantinople in 381 and the Council of Ephesus in 431. Oriental Orthodoxy shares much theology and many ecclesiastical traditions with the Eastern Orthodox Church; these include a similar doctrine of salvation[8] and a tradition of collegiality between bishops, as well as reverence of the Theotokos and use of the Nicene Creed.[9]

The primary theological difference between the two communions is the differing Christology. Oriental Orthodoxy rejects the Chalcedonian Definition, and instead adopts the miaphysite formula, believing that the human and divine natures of Christ are united. Historically, the early prelates of the Oriental Orthodox Churches thought that the Chalcedonian Definition implied a possible repudiation of the Trinity or a concession to Nestorianism.

Other differences include minor deviations in social teaching and different views on ecumenism. The Oriental Orthodox Churches are generally considered to be more conservative with regard to social issues as well more enthusiastic about ecumenical relations with non-Orthodox churches.

The break in communion between the Imperial Roman and Oriental Orthodox churches did not occur suddenly, but rather gradually over 2-3 centuries following the Council of Chalcedon.[10] Eventually the two communions developed separate institutions, and the Oriental Orthodox did not participate in any of the later ecumenical councils.

The Oriental Orthodox Churches maintain their own ancient apostolic succession.[11] The various churches are governed by holy synods, with a primus inter pares bishop serving as primate. The primates hold titles like patriarch, catholicos, and pope. The Alexandrian Patriarchate, the Antiochian Patriarchate along with Rome, was one of the most prominent sees of the early Christian Church.

Oriental Orthodoxy does not have a magisterial leader like the Roman Catholic Church, nor does the communion have a leader who can convene ecumenical synods like the Eastern Orthodox Church.

Non-Chalcedonian Christology[edit]

The schism between Oriental Orthodoxy and the adherents of Chalcedonian Christianity was based on differences in Christology. The First Council of Nicaea, in 325, declared that Jesus Christ is God, that is to say, "consubstantial" with the Father. Later, the third ecumenical council, the Council of Ephesus, declared that Jesus Christ, though divine as well as human, is only one being, or person (hypostasis). Thus, the Council of Ephesus explicitly rejected Nestorianism, the Christological doctrine that Christ was two distinct beings, one divine (the Logos) and one human (Jesus), who happened to inhabit the same body. The churches that later became Oriental Orthodoxy were firmly anti-Nestorian, and therefore strongly supported the decisions made at Ephesus.

Twenty years after Ephesus, the Council of Chalcedon reaffirmed the view that Jesus Christ was a single person, but at the same time declared that this one person existed "in two complete natures", one human and one divine. Those who opposed Chalcedon saw this as a concession to Nestorianism, or even as a conspiracy to convert the Christian Church to Nestorianism by stealth. As a result, over the following decades, they gradually separated from communion with those who accepted the Council of Chalcedon, and formed the body that is today called the Oriental Orthodox Churches.

At times, Chalcedonian Christians have referred to the Oriental Orthodox as being monophysites—that is to say, accusing them of following the teachings of Eutyches (c. 380 – c. 456), who argued that Jesus Christ was not human at all, but only divine. Monophysitism was condemned as heretical alongside Nestorianism, and to accuse a church of being monophysite is to accuse it of falling into the opposite extreme from Nestorianism. However, the Oriental Orthodox themselves reject this description as inaccurate, having officially condemned the teachings of both Nestorius and Eutyches. They define themselves as miaphysite instead, holding that Christ has one nature, but this nature is both human and divine.[12]

Today, the Oriental Orthodox Churches are in full communion with each other, but not with the Eastern Orthodox Church or any other churches; the Oriental Orthodox Churches while in communion do not form a single church as the Catholics or Eastern Orthodox. Slow dialogue towards restoring communion between the two Orthodox groups began in the mid-20th century,[13] and dialogue is also underway between Oriental Orthodoxy and the Catholic Church and others.[14] In 2017, the mutual recognition of baptism was restored between the Coptic Orthodox Church of Alexandria and the Catholic Church.[15] Also baptism is mutually recognized between the Armenian Apostolic Church and the Catholic Church.[16][17]

History[edit]

Post Council of Chalcedon (AD 451)[edit]

The schism between the Oriental Orthodox and the rest of Christendom occurred in the 5th century. The separation resulted in part from the refusal of Pope Dioscorus I of Alexandria and the other thirteen Egyptian bishops to accept the Christological dogmas promulgated by the Council of Chalcedon, which held that Jesus is in two natures: one divine and one human. They would accept only "of or from two natures" but not "in two natures".

To the hierarchs who would lead the Oriental Orthodox, the latter phrase was tantamount to accepting Nestorianism, which expressed itself in a terminology incompatible with their understanding of Christology. Nestorianism was understood as seeing Christ in two separate natures, human and divine, each with different actions and experiences; in contrast Cyril of Alexandria advocated the formula "One Nature of God the Incarnate Logos"[18] (or as others translate,[19] "One Incarnate Nature of the Word"), stressing the unity of the incarnation over all other considerations. It is not entirely clear that Nestorius himself was a Nestorian.

The Oriental Orthodox Churches were therefore often called "monophysite", although they reject this label, as it is associated with Eutychian monophysitism; they prefer the term "miaphysite". The Oriental Orthodox Churches reject what they consider to be the heretical monophysite teachings of Apollinaris of Laodicea and Eutyches, the Dyophysite definition of the Council of Chalcedon and the Antiochene Christology of Theodore of Mopsuestia, Nestorius, Theodoret, and Ibas of Edessa.

Christology, although important, was not the only reason for the Alexandrian Church's refusal to accept the declarations of the Council of Chalcedon; political, ecclesiastical and imperial issues were hotly debated during that period.

In the years following Chalcedon the patriarchs of Constantinople intermittently remained in communion with the non-Chalcedonian Patriarchs of Alexandria and Antioch (see Henotikon), while Rome remained out of communion with the latter and in unstable communion with Constantinople. It was not until 518 that the new Byzantine Emperor, Justin I (who accepted Chalcedon), demanded that the Church in the Roman Empire accept the Council's decisions.[20]

Justin ordered the replacement of all non-Chalcedonian bishops, including the patriarchs of Antioch and Alexandria. The extent of the influence of the Bishop of Rome in this demand has been a matter of debate. Justinian I also attempted to bring those monks who still rejected the decision of the Council of Chalcedon into communion with the greater church. The exact time of this event is unknown, but it is believed to have been between 535 and 548.

Saint Abraham of Farshut was summoned to Constantinople and he chose to bring with him four monks. Upon arrival, Justinian summoned them and informed them that they would either accept the decision of the council or lose their positions. Abraham refused to entertain the idea. Theodora tried to persuade Justinian to change his mind, seemingly to no avail. Abraham himself stated in a letter to his monks that he preferred to remain in exile rather than subscribe to a faith which he believed to be contrary to that of Athanasius of Alexandria.

20th century[edit]

By the 20th century the Chalcedonian schism was not seen with the same importance, and from several meetings between the authorities of the Holy See and the Oriental Orthodoxy, reconciling declarations emerged in the common statement of Syriac Patriarch Mar Ignatius Zakka I Iwas and the Roman Pope John Paul II in 1984:

The confusions and schisms that occurred between their Churches in the later centuries, they realize today, in no way affect or touch the substance of their faith, since these arose only because of differences in terminology and culture and in the various formulae adopted by different theological schools to express the same matter. Accordingly, we find today no real basis for the sad divisions and schisms that subsequently arose between us concerning the doctrine of Incarnation. In words and life we confess the true doctrine concerning Christ our Lord, notwithstanding the differences in interpretation of such a doctrine which arose at the time of the Council of Chalcedon.[21]

According to the canons of the Oriental Orthodox churches, the four bishops of Rome, Constantinople, Alexandria and Antioch were all given status as patriarchs; in other words, the ancient apostolic centres of Christianity, by the First Council of Nicaea (predating the schism)—each of the four patriarchs was responsible for those bishops and churches within his own area of the Church. Thus, the Bishop of Rome has always been held by the others to be fully sovereign within his own area, as well as "first-among-equals", due to the traditional belief that the Apostles Saint Peter and Saint Paul were martyred in Rome.[citation needed]

The technical reason for the schism was that the bishops of Rome and Constantinople excommunicated the non-Chalcedonian bishops in 451 for refusing to accept the "in two natures" teaching, thus declaring them to be out of communion.

The highest office in Oriental Orthodoxy is that of patriarch. There are patriarchs within the local Oriental Orthodox communities of the Coptic, Armenian, Eritrean, Ethiopian, Syriac, and Indian (Malankara) Orthodox churches. The title of pope, as used by the leading bishop of the Coptic Church, has the meaning of "Father" and is not a jurisdictional title.

Geographical distribution[edit]

According to the Encyclopedia of Religion, Oriental Orthodoxy is the Christian tradition "most important in terms of the number of faithful living in the Middle East", which, along with other Eastern Christian communions, represent an autochthonous Christian presence whose origins date further back than the birth and spread of Islam in the Middle East.[22]

It is the dominant religion in Armenia (94%) and ethnically Armenian unrecognized Nagorno-Karabakh Republic (95%).[23][24]

Oriental Orthodoxy is a prevailing religion in Ethiopia (43.1%), while Protestants account for 19.4% and Islam - 34.1%.[25] It is most widespread in two regions in Ethiopia: Amhara (82%) and Tigray (96%), as well as the capital city of Addis Ababa (75%). It is also one of two major religions in Eritrea (40%).[26]

It is a minority in Egypt (<20%),[27] Sudan (3–5%),[citation needed] Syria (2–3% out of the 10% of total Christians), Lebanon (10% of the 40% of Christians in Lebanon or 200,000 Armenians and members of the Church of the East) and Kerala, India (7% out of the 20% of total Christians in Kerala).[28] In terms of total number of members, the Ethiopian Church is the largest of all Oriental Orthodox churches, and is second among all Orthodox churches among Eastern and Oriental Churches (exceeded in number only by the Russian Orthodox Church).

Also of particular importance are the Armenian Patriarchate of Constantinople in Turkey and the Armenian Apostolic Church of Iran. These Oriental Orthodox churches represent the largest Christian minority in both of these predominantly Muslim countries, Turkey[29] and Iran.[30]

Organization[edit]

The Oriental Orthodox Churches are a communion of six autocephalous (that is, administratively completely independent) regional churches.[7] Each church has defined geographical boundaries of its jurisdiction and is ruled by its council of bishops or synod presided by a senior bishop–its primate (or first hierarch). The primate may carry the honorary title of pope (in the Alexandria tradition), patriarch, abuna (in the Ethiopian tradition) or catholicos.

Each regional church consists of constituent eparchies (or, dioceses) ruled by a bishop. Some churches have given an eparchy or group of eparchies varying degrees of autonomy (self-government). Such autonomous churches maintain varying levels of dependence on their mother church, usually defined in the document of autonomy.

Below is a list of the six autocephalous Orthodox churches forming the main body of Oriental Orthodox Christianity, all of which are titled equal to each other. Based on the definitions, the list is in the alphabetical order, with some of their constituent autonomous churches and exarchates listed as well.

- Coptic Orthodox Church of Alexandria

- Syriac Orthodox Church of Antioch

- Armenian Apostolic Church

- Malankara Orthodox Syrian Church

- Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church

- Eritrean Orthodox Tewahedo Church

There are a number of churches considered non-canonical, but whose members and clergy may or may not be in communion with the greater Oriental Orthodox communion. Examples include the Celtic Orthodox Church, the Ancient British Church, and lately the British Orthodox Church. These organizations have passed in and out of official recognition, but members rarely face excommunication when recognition is ended. The primates of these churches are typically referred to as episcopi vagantes or vagantes in short.

Internal disputes[edit]

There are numerous ongoing internal disputes within the Oriental Orthodox Churches. These disputes result in lesser or greater degrees of impaired communion.

Armenian Apostolic[edit]

The least divisive of these disputes is within the Armenian Apostolic Church, between the Catholicosate of Etchmiadzin and the Catholicosate of the Great House of Cilicia. The division of the two Catholicosates stemmed from frequent relocations of church headquarters due to political and military upheavals.

The division between the two sees intensified during the Soviet period. By some Western bishops and clergy the Holy See of Etchmiadzin was seen as a captive Communist puppet. Sympathizers of this established congregations independent of Etchmiadzin, declaring loyalty instead to the See based in Antelias in Lebanon. The division was formalized in 1956 when the Antelias (Cilician) See broke away from the Etchmiadzin See. Though recognising the supremacy of the Catholicos of All Armenians, the Catholicos of Cilicia administers the clergy and dioceses independently. The dispute, however, has not at all caused a breach in communion between the two churches.

Ethiopia[edit]

In 1992, following the abdication of Abune Merkorios and election of Abune Paulos, some Ethiopian Orthodox bishops in the United States maintained that the new election was invalid, and declared their independence from the Addis Ababa administration forming separate synod.[31] On 27 July 2018 representatives from both synods reached an agreement. According to the terms of the agreement, Abune Merkorios was reinstated as Patriarch alongside Abune Mathias (successor of Abune Paulos), who will continue to be responsible for administrative duties, and the two synods were merged into one synod, with any excommunications between them lifted.[32][33]

India[edit]

Indians who follow the Oriental Orthodox faith belong to the Malankara Orthodox Syrian Church and the Jacobite Syrian Christian Church. The two churches were united before 1912 and after 1958 but again separated in 1975. The Malankara Orthodox, also known as the Indian Orthodox Church, is an autocephalous church. It is headed by the Catholicos of the East and the Malankara Metropolitan. The Jacobite Syrian Christian Church is an autonomous body of the Syriac Orthodox Church in India. It is headed by regional head Catholicos of India.

The Malabar Independent Syrian Church also follows the Oriental Orthodox tradition but is not in communion with other Oriental Orthodox churches.

Occasional confusions[edit]

The Assyrian Church of the East is sometimes incorrectly described as an Oriental Orthodox church, though its origins lie in disputes that predated the Council of Chalcedon and it follows a different Christology from Oriental Orthodoxy. The historical Church of the East was the church of Greater Iran and declared itself separate from the state church of the Roman Empire in 424–27, years before Chalcedon. Theologically, the Church of the East was affiliated with the doctrine of Nestorianism, and thus rejected the Council of Ephesus, which declared Nestorianism heretical in 431. The Christology of the Oriental Orthodox churches in fact developed as a reaction against Nestorian Christology, which emphasizes the distinctness of the human and divine natures of Christ.

There are many overlapping ecclesiastical jurisdictions in India, mostly with a Syriac liturgical heritage centered in the state of Kerala. The autonomous Jacobite Syrian Christian Church, which comes under the Syriac Orthodox Church, is quite often confused with the autocephalous Malankara Orthodox Syrian Church as the similarity in their names.

See also[edit]

- Communion of Western Orthodox Churches

- Conference of Addis Ababa

- Eastern Christianity

- Eastern Orthodox Church

- Interparliamentary Assembly on Orthodoxy

- List of Christian denominations

- Oriental Orthodoxy in North America

References[edit]

Notes[edit]

Citations[edit]

- ^ Lamport, Mark A. (2018). Encyclopedia of Christianity in the Global South. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 601. ISBN 978-1-4422-7157-9.

Today these churches are also referred to as the Oriental Orthodox Churches and are made up of 50 million Christians.

- ^ "Orthodox Christianity in the 21st Century". Pew Research Center's Religion & Public Life Project. 8 November 2017.

Oriental Orthodoxy has separate self-governing jurisdictions in Ethiopia, Egypt, Eritrea, India, Armenia and Syria, and it accounts for roughly 20% of the worldwide Orthodox population.

- ^ "Orthodox churches (Oriental) — World Council of Churches". www.oikoumene.org.

- ^ Hindson & Mitchell 2013, p. 108.

- ^ "Orthodox churches (Oriental) — World Council of Churches". www.oikoumene.org.

- ^ a b Boutros Ghali 1991, pp. 1845b–1846a.

- ^ a b Keshishian 1994, pp. 103–108.

- ^ "The Transfiguration: Our Past and Our Future". Coptic Orthodox Diocese of Los Angeles.

- ^ St. Maurice and St. Verena Coptic Orthodox Church - Divine Liturgy on YouTube

- ^ "Chalcedonians". TheFreeDictionary. Retrieved June 11, 2016.

- ^ Krikorian 2010, pp. 45, 128, 181, 194, 206.

- ^ Davis 1990, p. 342.

- ^ "Middle Eastern Oriental Orthodox Common Declaration - March 17, 2001". sor.cua.edu.

- ^ "Dialogue with the Assyrian Church of the East and its Effect on the Dialogue with the Roman Catholic". Coptic Orthodox Church of Alexandria Diocese of Los Angeles, Southern California, and Hawaii. Retrieved 2 June 2016.

- ^ "Apostolic Journey to Egypt: Courtesy visit to H.H. Pope Tawadros II (Coptic Orthodox Patriarchate, Cairo - 28 April 2017) | Francis".

- ^ "Agreed on baptism in Germany". www.churchtimes.co.uk. Retrieved 2019-01-08.

- ^ Fanning 1907.

- ^ Pope Shenouda III of Alexandria (1999). "NATURE OF CHRIST" (PDF). copticchurch.net. St. Mark Coptic Orthodox Church. Retrieved 30 November 2014.

- ^ CYRIL OF ALEXANDRIA; Pusey, P. E. (Trans.). "FROM HIS SECOND BOOK AGAINST THE WORDS OF THEODORE". The Tertullian Project. Retrieved 30 November 2014.

- ^ Kirsch 1910.

- ^ "Common declaration of Pope John Paul II and His Holiness Moran Mar Ignatius Zakka I Iwas, Patriarch of Antioch and All the East (June 23, 1984) | John Paul II". www.vatican.va.

- ^ Encyclopedia of Religion. Christianity: Christianity in the Middle East (2nd ed.). Farmington Hills, MI: Thomson Gale. 2005. pp. 1672–1673.

- ^ UN Security Council resolutions on the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict

- ^ "Statement of the Co-Chairs of the OSCE Minsk Group". OSCE. Retrieved June 25, 2011.

- ^ "Ethiopia - Religion". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2019-10-25.

- ^ "Eritrea - Religion". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2019-10-25.

- ^ "The World Factbook: Egypt". CIA. Retrieved 7 October 2010.

- ^ "Church in India - Syrian Orthodox Church of India - Roman Catholic Church - Protestant Churches in India". Syrianchurch.org. Archived from the original on 16 October 2013. Retrieved 14 October 2013.

- ^ "Foreign Ministry: 89,000 minorities live in Turkey". Today's Zaman. 15 December 2008. Archived from the original on 20 May 2011. Retrieved 16 May 2011.

- ^ "Ahmadinejad: Religious minorities live freely in Iran (PressTV, 24 Sep 2009)". Archived from the original on January 15, 2016.

- ^ Goldman, Ari L. (22 September 1992). "U.S. Branch Leaves Ethiopian Orthodox Church". The New York Times. Retrieved 29 April 2016.

- ^ Dickinson, Augustine (31 July 2018). "Decades-Old Schism in the Ethiopian Church Mended". Ethiopicist Blog. Retrieved 8 August 2018.

- ^ Kibriye, Solomon (27 July 2018). "Ethiopian Orthodox Unity Declaration Document in English". Orthodoxy Cognate Page. Retrieved 8 August 2018.

Sources[edit]

- Betts, Robert B. (1978). Christians in the Arab East: A Political Study (2nd rev. ed.). Athens: Lycabettus Press. ISBN 9780804207966.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Boutros Ghali, Mirrit (1991). "Oriental Orthodox Churches". In Atiya, Aziz Suryal (ed.). The Coptic Encyclopedia. Volume 6. New York: Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-02-897035-6. OCLC 22808960.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Charles, Robert H. (2007) [1916]. The Chronicle of John, Bishop of Nikiu: Translated from Zotenberg's Ethiopic Text. Merchantville, NJ: Evolution Publishing. ISBN 9781889758879.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Davis, Leo Donald (1990). The First Seven Ecumenical Councils (325-787): Their History and Theology. Liturgical Press. ISBN 978-0-8146-5616-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fanning, William Henry Windsor (1907). . In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. 2. New York: Robert Appleton Company.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hindson, Ed; Mitchell, Dan (2013). The Popular Encyclopedia of Church History. Harvest House Publishers. ISBN 978-0-7369-4806-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Keshishian, Aram (1994). "The Oriental Orthodox Churches". The Ecumenical Review. 46 (1): 103–108. doi:10.1111/j.1758-6623.1994.tb02911.x. ISSN 0013-0796.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kirsch, Johann Peter (1910). . In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. 7. New York: Robert Appleton Company.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Krikorian, Mesrob K. (2010). Christology of the Oriental Orthodox Churches: Christology in the Tradition of the Armenian Apostolic Church. Peter Lang. ISBN 9783631581216.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Meyendorff, John (1989). Imperial unity and Christian divisions: The Church 450-680 A.D. The Church in history. 2. Crestwood, NY: St. Vladimir's Seminary Press. ISBN 9780881410556.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ostrogorsky, George (1956). History of the Byzantine State. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links[edit]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Oriental Orthodoxy. |

- Orthodox Joint Commission

- The Standing Conference of Oriental Orthodox Churches in America

- Encyclical, Pope Benedict XIV, Allatae Sunt (On the observance of Oriental Rites), 1755

- Common Declaration of Pope John Paul II and HH Mar Ignatius Zakka I Iwas

- Joint Declarations Between the Syriac Orthodox and Roman Catholic Churches

- Dialogue with the Oriental Orthodox Churches on the Anglican Communion Website

- Dialogue with the Oriental Orthodox Churches on the Vatican Website

- The Rejection of the Term Theotokos by Nestorius Constantinople