Baptism of Jesus

The Baptism of Christ, an egg-on-poplar painting by Piero della Francesca, produced after 1437 and now in the National Gallery, London.[1] | |

| Date | 1st century AD |

|---|---|

| Location | Near present-day Al-Maghtas, Jordan |

| Participants | Jesus, John the Baptist |

The baptism of Jesus by John the Baptist is a major event in the life of Jesus is described in three of the gospels: Matthew, Mark and Luke.[a] It is considered to have taken place at Al-Maghtas, located in Jordan.

Most modern theologians view the baptism of Jesus by John the Baptist as a historical event to which a high degree of certainty can be assigned.[2][3][4][5][6] Along with the crucifixion of Jesus, most biblical scholars view it as one of the two historically certain facts about him, and often use it as the starting point for the study of the historical Jesus.[7]

The baptism is one of the events in the narrative of the life of Jesus in the canonical Gospels; others include the Transfiguration, Crucifixion, Resurrection, and Ascension.[8][9] Most Christian denominations view the baptism of Jesus as an important event and a basis for the Christian rite of baptism (see also Acts 19:1–7). In Eastern Christianity, Jesus' baptism is commemorated on 6 January (the Julian calendar date of which corresponds to 19 January on the Gregorian calendar), the feast of Epiphany.[10] In the Roman Catholic Church, the Anglican Communion, the Lutheran Churches and some other Western denominations, it is recalled on a day within the following week, the feast of the baptism of the Lord. In Roman Catholicism, the baptism of Jesus is one of the Luminous Mysteries sometimes added to the Rosary. It is a Trinitarian feast in the Eastern Orthodox Churches.

In the Synoptic Gospels[edit]

Mark, Matthew, and Luke depict the baptism in parallel passages. In all three gospels, the Holy Spirit is depicted as descending upon Jesus immediately after his baptism accompanied by a voice from Heaven, but the accounts of Luke and Mark record the voice as addressing Jesus by saying "You are my beloved Son, in whom I am well pleased", while in Matthew the voice addresses the crowd "This is my beloved Son, in whom I am well pleased" (Matthew 3:13–17; Mark 1:9–11; Luke 3:21–23).[11][12][13]

After the baptism, the Synoptic gospels describe the temptation of Jesus, where Jesus withdrew to the Judean desert to fast for forty days and nights.

Matthew[edit]

In Matthew 3:14, upon meeting Jesus, John said: "I have need to be baptized of thee, and comest thou to me?"[14] However, Jesus convinces John to baptize him nonetheless.[13] Matthew uniquely records that the voice from heaven addresses the crowd, rather than addressing Jesus himself as in Mark and Luke.

Mark[edit]

Mark's account is roughly parallel to that of Matthew, except for Matthew 3:14-15 describing John's initial reluctance and eventual consent to baptize Jesus, which is not described by Mark. Mark uses an unusual word for the opening of the heavens, Greek: σχίζω, schizō, which means “tearing” or “ripping” (Mark 1:10). It forms a verbal thread (Leitwortstil) with the rending of the Temple veil in Mark 15:38, inviting comparison between the two episodes.[15]

Luke[edit]

Luke 1 begins with the birth of John the Baptist, heralded to his father Zacharias by the angel Gabriel. Six months later Gabriel appears to the Virgin Mary with an announcement of the birth of Jesus, at the Annunciation. At the same, Gabriel also announces to Mary the coming birth of John the Baptist, to her kinswoman Elizabeth, who is the wife of Zacharias. Mary immediately sets out to visit her kinswoman Elizabeth, and stays with her until John's birth. Luke strongly contrasts the reactions of Zacharias and Mary to these two respective births; and the lives of John and Jesus are intertwined.

Luke uniquely depicts John as showing public kindness to tax collectors and encouraging the giving of alms to the poor (as in Luke 3:11). Luke records that Jesus was praying when Heaven was opened and the Holy Spirit descended on him. Luke clarifies that the spirit descended in the "bodily form" of a dove, as opposed to merely "descending like" a dove. In Acts 10:37–38, the ministry of Jesus is described as following "the baptism which John preached".[16]

In the Gospel of John[edit]

In John 1:29–33 rather than a direct narrative, John the Baptist bears witness to the spirit descending like a dove.[11][18]

The Gospel of John (John 1:28) specifies "Bethabara beyond Jordan", i.e., Bethany in Perea as the location where John was baptizing when Jesus began choosing disciples, and in John 3:23 there is mention of further baptisms in Ænon "because there was much water there".[19][20]

John 1:35–37 narrates an encounter, between Jesus and two of his future disciples, who were then disciples of John the Baptist.[21][22] The episode in John 1:35–37 forms the start of the relationship between Jesus and his future disciples. When John the Baptist called Jesus the Lamb of God, the "two disciples heard him speak, and they followed Jesus".[16][23][24] One of the disciples is named Andrew, but the other remains unnamed, and Raymond E. Brown raises the question of his being the author of the Gospel of John himself.[18][25] In the Gospel of John, the disciples follow Jesus thereafter, and bring other disciples to him, and Acts 18:24–19:6 portrays the disciples of John as eventually merging with the followers of Jesus.[18][21]

In the Gospel of the Nazarenes[edit]

According to the non-canonical Gospel of the Nazarenes, the idea of being baptized by John came from the mother and brothers of Jesus, and Jesus himself, originally opposed, reluctantly accepted it.[26] Benjamin Urrutia avers that this version is supported by the Criterion of Embarrassment, since followers of Jesus would not have invented an episode in which Jesus changes his mind and comes to accept someone else's plan. Plus, the story came from the community that included the family of Jesus, who would have guaranteed the authenticity of the narrative.[27]

Location[edit]

The Gospel of John (John 3:23) refers to Enon near Salim as one place where John the Baptist baptized people, "because there was much water there".[19][20] Separately, John 1:28 states that John the Baptist was baptizing in "Bethany beyond the Jordan".[19] This is not the village Bethany just east of Jerusalem, but is generally considered to be the town Bethany, also called Bethabara in Perea on the Eastern bank of the Jordan near Jericho.[20] In the 3rd century Origen, who moved to the area from Alexandria, suggested Bethabara as the location.[28] In the 4th century, Eusebius of Caesarea stated that the location was on the west bank of the Jordan, and following him, the early Byzantine Madaba Map shows Bethabara as (Βέθαβαρά).[28]

The biblical baptising is related to springs and a Wadi (al-Kharrar) close to the Eastern site of the Jordan River,[29] not the Jordan itself.[30] The pilgrimage sites, important for both Christians and Jews have shifted place during history. The site of Al-Maghtas (baptism, or immersion in Arabic) on the East side of the River in Jordan has been deemed the earliest place of worship. This site was found following UNESCO-sponsored excavations.[31] Al-Maghtas was visited by Pope John Paul II in March 2000, and he said: "In my mind I see Jesus coming to the waters of the river Jordan not far from here to be baptized by John the Baptist".[32] The Muslim conquest put an end to the Byzantine buildings on the east bank of the Jordan River, the later reverence took place just across the river in the West Bank at Qasr el Yahud.[33]

Chronology[edit]

The baptism of Jesus is generally considered as the start of his ministry, shortly after the start of the ministry of John the Baptist.[34][35][36] Luke 3:1–2 states that:[37][38]

In the fifteenth year of the reign of Tiberius Caesar—when Pontius Pilate was governor of Judea ... , the word of God came to John son of Zechariah in the wilderness.

There are two approaches to determining when the reign of Tiberius Caesar started.[39] The traditional approach is that of assuming that the reign of Tiberius started when he became co-regent in 11 AD, placing the start of the ministry of John the Baptist around 26 AD. However, some scholars assume it to be upon the death of his predecessor Augustus Caesar in 14 AD, implying that the ministry of John the Baptist began in 29 AD.[39]

The generally assumed dates for the start of the ministry of John the Baptist based on this reference in the Gospel of Luke are about 28–29 AD, with the ministry of Jesus with his baptism following it shortly thereafter.[37][38][40][41][42]

Historicity[edit]

Most modern scholars believe that John the Baptist performed a baptism on Jesus, and view it as a historical event to which a high degree of certainty can be assigned.[2][3][4][5] James Dunn states that the historicity of the baptism and crucifixion of Jesus "command almost universal assent".[7] Dunn states that these two facts "rank so high on the 'almost impossible to doubt or deny' scale of historical facts" that they are often the starting points for the study of the historical Jesus.[7] John Dominic Crossan states that it is historically certain that Jesus was baptised by John in the Jordan.[6]

In the Antiquities of the Jews (18.5.2) 1st-century historian Flavius Josephus also wrote about John the Baptist and his eventual death in Perea.[43][44]

The existence of John the Baptist within the same time frame as Jesus, and his eventual execution by Herod Antipas is attested to by 1st-century historian Flavius Josephus and the overwhelming majority of modern scholars view Josephus' accounts of the activities of John the Baptist as authentic.[45][46] Josephus establishes a key connection between the historical events he recorded and specific episodes that appear in the gospels.[45] The reference in the Antiquities of the Jews by Josephus to John's popularity among the crowds (Ant 18.5.2) and how he preached his baptism is considered a reliable historical datum.[47][48] Unlike the gospels, Josephus does not relate John and Jesus, and does not state that John's baptisms were for the remission of sins.[47][48][49] However, almost all modern scholars consider the Josephus passage on John to be authentic in its entirety and view the variations between Josephus and the gospels as indications that the Josephus passages are authentic, for a Christian interpolator would have made them correspond to the Christian traditions.[50][51]

One of the arguments in favour of the historicity of the baptism of Jesus by John is that it is a story which the early Christian Church would have never wanted to invent, typically referred to as the criterion of embarrassment in historical analysis.[5][6][52] Based on this criterion, given that John baptised for the remission of sins, and Jesus was viewed as without sin, the invention of this story would have served no purpose, and would have been an embarrassment given that it positioned John above Jesus.[5][52][53] The Gospel of Matthew attempts to offset this problem by having John feel unworthy to baptise Jesus and Jesus giving him permission to do so in Matthew 3:14–15.[54]

The gospels are not the only references to the baptisms performed by John and in Acts 10:37–38, the apostle Peter refers to how the ministry of Jesus followed "the baptism which John preached".[55] Another argument used in favour of the historicity of the baptism is that multiple accounts refer to it, usually called the criterion of multiple attestation.[54] Technically, multiple attestation does not guarantee authenticity, but only determines antiquity.[56] However, for most scholars, together with the criterion of embarrassment it lends credibility to the baptism of Jesus by John being a historical event.[54][57][58][59]

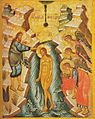

Artistic depictions[edit]

While the gospel of Luke is explicit about the Spirit of God descending in the shape of a dove, the wording of Matthew is vague enough that it could be interpreted only to suggest that the descent was in the style of a dove. Although a variety of symbolisms were attached to doves at the time these passages were written, the dove imagery has become a well known symbol for the Holy Spirit in Christian art.[60][61] Depictions of the baptismal scene typically show the sky opening and the Holy Spirit descending as a dove towards Jesus.[62]

Arian Baptistry, Ravenna, 6th-century mosaic

High cross, Kells, Ireland, 10th century carving in stone

The Baptism of Christ by Andrea del Verrocchio and Leonardo da Vinci, c. 1475

Juan Navarrete, 1567

Chinese porcelain, Qing dynasty, early 18th century

Eastern Orthodox icon

Gerard David – Triptych of Jan Des Trompes, c. 1505

Gregorio Fernández, c. 1630

Grigory Gagarin, c. 1840–1850

Music[edit]

The reformer Martin Luther wrote a hymn about baptism, based on biblical accounts about the baptism of Jesus, "Christ unser Herr zum Jordan kam" (1541). It is the basis for a cantata by Johann Sebastian Bach, Christ unser Herr zum Jordan kam, BWV 7, first performed on 24 June 1724.

See also[edit]

| Events in the |

| Life of Jesus according to the canonical gospels |

|---|

|

|

In rest of the NT |

|

Portals: |

- Ænon

- Al Maghtas

- Bethabara

- Chronology of Jesus

- Jesus in Christianity

- Life of Jesus in the New Testament

- Ministry of Jesus

- New Testament places associated with Jesus

- Qasr el Yahud

- Transfiguration of Jesus

Notes[edit]

- ^ The John's gospel does not directly describe Jesus' baptism.

References[edit]

- ^ "The Baptism of Christ". National Gallery.

- ^ a b The Gospel of Matthew by Daniel J. Harrington 1991 ISBN 0-8146-5803-2 p. 63

- ^ a b Christianity: A Biblical, Historical, and Theological Guide by Glenn Jonas, Kathryn Muller Lopez 2010, pp. 95–96

- ^ a b Studying the Historical Jesus: Evaluations of the State of Current Research by Bruce Chilton, Craig A. Evans 1998 ISBN 90-04-11142-5 pp. 187–98

- ^ a b c d Jesus as a Figure in History: How Modern Historians View the Man from Galilee by Mark Allan Powell 1998 ISBN 0-664-25703-8 p. 47

- ^ a b c Who Is Jesus? by John Dominic Crossan, Richard G. Watts 1999 ISBN 0-664-25842-5 pp. 31–32

- ^ a b c Jesus Remembered by James D. G. Dunn 2003 ISBN 0-8028-3931-2 p. 339

- ^ Essays in New Testament Interpretation by Charles Francis Digby Moule 1982 ISBN 0-521-23783-1 p. 63

- ^ The Melody of Faith: Theology in an Orthodox Key by Vigen Guroian 2010 ISBN 0-8028-6496-1 p. 28

- ^ Богоявление и Рождество Христово

- ^ a b Jesus of History, Christ of Faith by Thomas Zanzig 2000 ISBN 0-88489-530-0 p. 118

- ^ Eerdmans Commentary on the Bible by James D. G. Dunn, John William Rogerson 2003 ISBN 0-8028-3711-5 p. 1010

- ^ a b The Synoptics: Matthew, Mark, Luke by Ján Majerník, Joseph Ponessa, Laurie Watson Manhardt 2005 ISBN 1-931018-31-6 pp. 27–31

- ^ Matthew 3:14 NIV

- ^ David Rhoads, Joanna Dewey, and Donald Michie, Mark as Story: An Introduction to the Narrative of a Gospel, 3rd ed. (Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 2012), 48; James L. Resseguie, Narrative Criticism of the New Testament: An Introduction (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2005), 44.

- ^ a b Jesus of Nazareth by Duane S. Crowther 1999 ISBN 0-88290-656-9 p. 77

- ^ The Lamb of God by Sergei Bulgakov 2008 ISBN 0-8028-2779-9 p. 263

- ^ a b c The Gospel and Epistles of John: A Concise Commentary by Raymond Edward Brown 1988 ISBN 978-0-8146-1283-5 pp. 25–27

- ^ a b c Big Picture of the Bible – New Testament by Lorna Daniels Nichols 2009 ISBN 1-57921-928-4 p. 12

- ^ a b c John by Gerard Stephen Sloyan 1987 ISBN 0-8042-3125-7 p. 11

- ^ a b The People's New Testament Commentary by Eugene M. Boring and Fred B. Craddock 2010, Westminster John Knox Press ISBN 0-664-23592-1 pp. 292-93

- ^ New Testament History by Richard L. Niswonger 1992 ISBN 0-310-31201-9 pp. 143–46

- ^ The Life and Ministry of Jesus: The Gospels by Douglas Redford 2007 ISBN 0-7847-1900-4 p. 92

- ^ A Summary of Christian History by Robert A. Baker, John M. Landers 2005 ISBN 0-8054-3288-4 pp. 6–7

- ^ The Disciple Whom Jesus Loved by J. Phillips 2004 ISBN 0-9702687-1-8 pp. 121–23

- ^ Jerome, quoting "The Gospel According to the Hebrews" in Dialogue Against Pelagius III:2

- ^ Guy Davenport and Benjamin Urrutia, The Logia of Yeshua / The Sayings of Jesus (1996), ISBN 1-887178-70-8 p. 51.

- ^ a b Jesus and Archaeology by James H. Charlesworth 2006, Eedrsmans ISBN 0-8028-4880-X pp. 437–39

- ^ The Synoptics by Jan Majernik, Joseph Ponessa and Laurie Manhardt 2005 ISBN 1-931018-31-6 p. 29

- ^ "Wo Johannes taufte". ZEIT ONLINE. Rosemarie Noack. 22 December 1999. Retrieved 9 December 2015.

- ^ Staff writers (28 July 2011). "Israel will reopen (Israeli) site of the baptism of Jesus". AsiaNews.it. Retrieved 31 July 2011.

- ^ Vatican website: Address of John Paul II at Al-Maghtas Archived 16 July 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "No evidence, but UN says Jesus baptized on Jordan's side of river, not Israel's". Times of Israel. 13 July 2015. Retrieved 26 November 2015.

- ^ Jesus and the Gospels: An Introduction and Survey by Craig L. Blomberg 2009 ISBN 0-8054-4482-3 pp. 224–29

- ^ Christianity: An Introduction by Alister E. McGrath 2006 ISBN 978-1-4051-0901-7pp. 16–22

- ^ The Cradle, the Cross, and the Crown: An Introduction to the New Testament by Andreas J. Köstenberger, L. Scott Kellum 2009 ISBN 978-0-8054-4365-3 po. 140–41

- ^ a b Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible 2000 Amsterdam University Press ISBN 90-5356-503-5 p. 249

- ^ a b The Bible Knowledge Background Commentary: Matthew-Luke, Volume 1 by Craig A. Evans 2003 ISBN 0-7814-3868-3 pp. 67–69

- ^ a b Luke 1–5: New Testament Commentary by John MacArthur 2009 ISBN 0-8024-0871-0 p. 201

- ^ The Cradle, the Cross, and the Crown: An Introduction to the New Testament by Andreas J. Köstenberger, L. Scott Kellum 2009 ISBN 978-0-8054-4365-3 p. 114

- ^ Christianity and the Roman Empire: Background Texts by Ralph Martin Novak 2001 ISBN 1-56338-347-0 pp. 302–03

- ^ Hoehner, Harold W (1978). Chronological Aspects of the Life of Christ. Zondervan. pp. 29–37. ISBN 0-310-26211-9.

- ^ Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible 2000 ISBN 90-5356-503-5 p. 583

- ^ Behold the Man: The Real Life of the Historical Jesus by Kirk Kimball 2002 ISBN 978-1-58112-633-4 p. 654

- ^ a b Craig Evans, 2006 "Josephus on John the Baptist" in The Historical Jesus in Context edited by Amy-Jill Levine et al. Princeton Univ Press ISBN 978-0-691-00992-6 pp. 55–58

- ^ The New Complete Works of Josephus by Flavius Josephus, William Whiston, Paul L. Maier ISBN 0-8254-2924-2 pp. 662–63

- ^ a b John the Baptist: Prophet of Purity for a New Age by Catherine M. Murphy 2003 ISBN 0-8146-5933-0 p. 53

- ^ a b Jesus & the Rise of Early Christianity: A History of New Testament Times by Paul Barnett 2009 ISBN 0-8308-2699-8 p. 122

- ^ Claudia Setzer, "Jewish Responses to Believers in Jesus", in Amy-Jill Levine, Marc Z. Brettler (editors), The Jewish Annotated New Testament, p. 576 (New Revised Standard Version, Oxford University Press, 2011). ISBN 978-0-19-529770-6

- ^ Evans, Craig A. (2006). "Josephus on John the Baptist". In Levine, Amy-Jill. The Historical Jesus in Context. Princeton Univ Press. ISBN 978-0-691-00992-6. pp. 55–58

- ^ Eddy, Paul; Boyd, Gregory (2007). The Jesus Legend: A Case for the Historical Reliability of the Synoptic Jesus Tradition. ISBN 0-8010-3114-1. p. 130

- ^ a b Jesus of Nazareth: An Independent Historian's Account of His Life and Teaching by Maurice Casey 2010 ISBN 0-567-64517-7 p. 35

- ^ The Historical Jesus: a Comprehensive Guide by Gerd Theissen, Annette Merz 1998 ISBN 0-8006-3122-6 p. 207

- ^ a b c John the Baptist: Prophet of Purity for a New Age by Catherine M. Murphy 2003 ISBN 0-8146-5933-0 pp. 29–30

- ^ Who is Jesus?: An Introduction to Christology by Thomas P. Rausch 2003 ISBN 978-0-8146-5078-3 p. 77

- ^ Jesus and His Contemporaries: Comparative Studies by Craig A. Evans 2001 ISBN 0-391-04118-5 p. 15

- ^ An Introduction to the New Testament and the Origins of Christianity by Delbert Royce Burkett 2002 ISBN 0-521-00720-8 pp. 247–48

- ^ Who is Jesus? by Thomas P. Rausch 2003 ISBN 978-0-8146-5078-3 p. 36

- ^ The Relationship between John the Baptist and Jesus of Nazareth: A Critical Study by Daniel S. Dapaah 2005 ISBN 0-7618-3109-6 p. 91

- ^ Clarke, Howard W. The Gospel of Matthew and its Readers: A Historical Introduction to the First Gospel. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2003.

- ^ Albright, W.F. and C.S. Mann. "Matthew". The Anchor Bible Series. New York: Doubleday & Company, 1971.

- ^ Medieval Art: A Topical Dictionary by Leslie Ross 1996 ISBN 978-0-313-29329-0 p. 30

External links[edit]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Baptism of Jesus Christ. |

- Baptism of Jesus – Catholic Encyclopedia

Baptism of Jesus

| ||

| Preceded by Ministry of John the Baptist, further preceded by Finding in the Temple |

New Testament Events |

Succeeded by Temptation of Jesus |