History of Christianity

| Part of a series on |

| Christianity |

|---|

|

|

|

The history of Christianity concerns the Christian religion, Christendom, and the Church with its various denominations, from the 1st century to the present.

Christianity originated with the ministry of Jesus in the 1st century Roman province of Judea. According to the Gospels, Jesus was a Jewish teacher and healer who proclaimed the imminent kingdom of God and was crucified c. AD 30–33. His followers believed that he was then raised from the dead and exalted by God, and would return soon at the inception of God's kingdom.

The earliest followers of Jesus were apocalyptic Jewish Christians. The inclusion of gentiles in the developing early Christian Church caused a schism between Judaism and Jewish Christianity during the first two centuries of the Christian Era. In 313, Emperor Constantine I issued the Edict of Milan legalizing Christian worship. In 380, with the Edict of Thessalonica put forth under Theodosius I, the Roman Empire officially adopted Trinitarian Christianity as its state religion, and Christianity established itself as a predominantly gentile religion in the state church of the Roman Empire. Christological debates about the human and divine nature of Jesus consumed the Christian Church for a couple of centuries, and seven ecumenical councils were called to resolve these debates. Arianism was condemned at the First Council of Nicea (325), which supported the Trinitarian doctrine as expounded in the Nicene Creed.

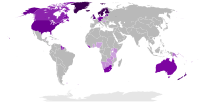

In the early Middle Ages, missionary activities spread Christianity towards the west among German peoples. During the High Middle Ages, eastern and western Christianity grew apart, leading to the East–West Schism of 1054. Growing criticism of the Roman Catholic ecclesiological structure and its behaviour led to the Protestant movement of the 16th century and the split of western Christianity. Since the Renaissance era, with colonialism inspired by the Church, Christianity has expanded throughout the world.[1] Today there are more than two billion Christians worldwide, and Christianity has become the world's largest religion.[2] Within the last century, as the influence of Christianity has waned in the West, it has rapidly grown in the East and the Global South in China, South Korea and much of sub-Saharan Africa.

Origins[edit]

Jewish-Hellenistic background[edit]

The religious climate of 1st century Judea was diverse, with numerous Judaic sects. The ancient historian Josephus describes four prominent groups in the Judaism of the time: Pharisees, Sadducees, Essenes and Zealots. This led to unrest, and the 1st century BC and 1st century AD had numerous charismatic religious leaders, contributing to what would become the Mishnah of rabbinic Judaism, including Yohanan ben Zakkai and Hanina ben Dosa. Jewish messianism, and the Jewish messiah concept, has its roots in the apocalyptic literature of the 2nd century BC to 1st century BC, promising a future "anointed" leader (messiah or king) from the Davidic line to resurrect the Israelite Kingdom of God, in place of the foreign rulers of the time.

Ministry of Jesus[edit]

The main sources of information regarding Jesus' life and teachings are the four canonical gospels, and to a lesser extent the Acts of the Apostles and the Pauline epistles. According to the Gospels, Jesus was a Jewish teacher and healer who was crucified c.30–33 AD. His followers believed that he was raised from death and exalted by God because of his faithfulness.

Early Christianity (c. 31/33–324)[edit]

Early Christianity is generally reckoned by church historians to begin with the ministry of Jesus (c. 27-30) and end with the First Council of Nicaea (325). It is typically divided into two periods: the Apostolic Age (c. 30–100, when the first apostles were still alive) and the Ante-Nicene Period (c. 100–325).[3]

Apostolic Age[edit]

The Apostolic Age is named after the Apostles and their missionary activities. It holds special significance in Christian tradition as the age of the direct apostles of Jesus. A primary source for the Apostolic Age is the Acts of the Apostles, but its historical accuracy is questionable and its coverage is partial, focusing especially from Acts 15:36 onwards on the ministry of Paul, and ending around 62 AD with Paul preaching in Rome under house arrest.

The earliest followers of Jesus were apocalyptic Jewish Christians. The early Christian groups were strictly Jewish, such as the Ebionites and the early Christian community in Jerusalem, led by James, the brother of Jesus. According to Acts 9:1–2, they described themselves as "disciples of the Lord" and [followers] "of the Way", and according to Acts 11:26 a settled community of disciples at Antioch were the first to be called "Christians". Some of the early Christian communities attracted gentile God-fearers, who already visited Jewish synagogues. The inclusion of gentiles posed a problem, as they could not fully observe the Halakha. Saul of Tarsus, commonly known as Paul the Apostle, persecuted the early Jewish Christians, then converted and started his mission among the gentiles. The main concern of Paul's letters is the inclusion of gentiles into God's New Covenant, deeming faith in Christ sufficient for righteousness. Because of this inclusion of gentiles, early Christianity changed of character and gradually grew apart from Judaism and Jewish Christianity during the first two centuries of the Christian Era.

The Gospels and New Testament epistles contain early creeds and hymns, as well as accounts of the Passion, the empty tomb, and Resurrection appearances.[5] Early Christianity slowly spread to pockets of believers among Aramaic-speaking peoples along the Mediterranean coast and also to the inland parts of the Roman Empire and beyond that into the Parthian Empire and the later Sasanian Empire, including Mesopotamia, which was dominated at different times and to varying extents by these empires.[6]

Ante-Nicene period[edit]

The ante-Nicene period (literally meaning "before Nicaea") was the period following the Apostolic Age down to the First Council of Nicaea in 325. By the beginning of the Nicene period, the Christian faith had spread throughout Western Europe and the Mediterranean Basin, and to North Africa and the East. A more formal Church structure grew out of the early communities, and variant Christian doctrines developed. Christianity grew apart from Judaism, creating its own identity by an increasingly harsh rejection of Judaism, of Jewish practices, and an acceptance of what some[which?] scholars have called religious anti-semitism, however, many[which?] modern day Christian theologians reject this accusation. [7]

Developing church structure[edit]

The number of Christians grew by approximately 40% per decade during the first and second centuries.[8] In the post-Apostolic church, bishops emerged as overseers of urban Christian populations, and a hierarchy of clergy gradually took on the form of episkopos (overseers, inspectors; and the origin of the term bishop) and presbyters (elders; and the origin of the term priest), and then deacons (servants). But this emerged slowly and at different times in different locations. Clement, a 1st-century bishop of Rome, refers to the leaders of the Corinthian church in his epistle to Corinthians as bishops and presbyters interchangeably. The New Testament writers also use the terms overseer and elders interchangeably and as synonyms.[9]

Variant Christianities[edit]

The Ante-Nicene period saw the rise of a great number of Christian sects, cults and movements with strong unifying characteristics lacking in the apostolic period. They had different interpretations of Scripture, particularly the divinity of Jesus and the nature of the Trinity. Many variations in this time defy neat categorizations, as various forms of Christianity interacted in a complex fashion to form the dynamic character of Christianity in this era. The Post-Apostolic period was diverse both in terms of beliefs and practices. In addition to the broad spectrum of general branches of Christianity, there was constant change and diversity that variably resulted in both internecine conflicts and syncretic adoption.[10][11][12][13]

Development of the Biblical canon[edit]

The Pauline epistles were circulating in collected form by the end of the 1st century.[14] By the early 3rd century, there existed a set of Christian writings similar to the current New Testament, though there were still disputes over the canonicity of Hebrews, James, II Peter, II and III John, and Revelation.[15][16] By the 4th century, there existed unanimity in the West concerning the New Testament canon,[17] and by the 5th century the East, with a few exceptions, had come to accept the Book of Revelation and thus had come into harmony on the matter of the canon.[18]

Early orthodox writings[edit]

As Christianity spread, it acquired certain members from well-educated circles of the Hellenistic world; they sometimes became bishops. They produced two sorts of works: theological and "apologetic", the latter being works aimed at defending the faith by using reason to refute arguments against the veracity of Christianity. These authors are known as the Church Fathers, and study of them is called patristics. Notable early fathers include Ignatius of Antioch, Polycarp, Justin Martyr, Irenaeus, Tertullian, Clement of Alexandria, and Origen.

Early art[edit]

Christian art emerged relatively late, and the first known Christian images emerge from about 200 AD,[19] though there is some literary evidence that small domestic images were used earlier. The oldest known Christian paintings are from the Roman catacombs, dated to about 200, and the oldest Christian sculptures are from sarcophagi, dating to the beginning of the 3rd century.[20]

Although many Hellenistic Jews seem to have had images of religious figures, as at the Dura-Europos synagogue, the traditional Mosaic prohibition of "graven images" no doubt retained some effect, although never proclaimed by theologians. This early rejection of images, and the necessity to hide Christian practise from persecution, leaves few archaeological records regarding early Christianity and its evolution.[20]

Persecutions and legalisation[edit]

There was no empire-wide persecution of Christians until the reign of Decius in the third century.[21] The last and most severe persecution organised by the imperial authorities was the Diocletianic Persecution, 303–311.[22] The Edict of Serdica was issued in 311 by the Roman Emperor Galerius, officially ending the persecution in the East. With the passage in 313 AD of the Edict of Milan, in which the Roman Emperors Constantine the Great and Licinius legalised the Christian religion, persecution of Christians by the Roman state ceased.[23]

Late antiquity (313–476)[edit]

Influence of Constantine[edit]

How much Christianity Constantine adopted at this point is difficult to discern,[24] but his accession was a turning point for the Christian Church. Constantine supported the Church financially, built various basilicas, granted privileges (e.g., exemption from certain taxes) to clergy, promoted Christians to some high offices, and returned confiscated property.[25] Constantine played an active role in the leadership of the Church. In 316, he acted as a judge in a North African dispute concerning the Donatist controversy. More significantly, in 325 he summoned the Council of Nicaea, the first ecumenical council. Constantine thus established a precedent for the emperor as responsible to God for the spiritual health of their subjects, and thus with a duty to maintain orthodoxy. The emperor was to enforce doctrine, root out heresy, and uphold ecclesiastical unity.[26]

Constantine's son's successor, his nephew Julian, under the influence of his adviser Mardonius, renounced Christianity and embraced a Neo-platonic and mystical form of paganism, shocking the Christian establishment.[27] He began reopening pagan temples, modifying them to resemble Christian traditions such as the episcopal structure and public charity (previously unknown in Roman paganism). Julian's short reign ended when he died while campaigning in the East.

Arianism and the first ecumenical councils[edit]

Arianism was a popular doctrine of the 4th century, which was the denial of the divinity of Christ as propounded by Arius. Although this doctrine was condemned as heresy and eventually eliminated by the Roman Church, it remained popular underground for some time. In the late 4th century, Ulfilas, a Roman bishop and an Arian, was appointed as the first bishop to the Goths, the Germanic peoples in much of Europe at the borders of and within the Empire. Ulfilas spread Arian Christianity among the Goths, firmly establishing the faith among many of the Germanic tribes, thus helping to keep them culturally distinct.[28]

During this age, the first ecumenical councils were convened. They were mostly concerned with Christological disputes. The First Council of Nicaea (325) and the First Council of Constantinople (381) resulted in condemning Arian teachings as heresy and producing the Nicene Creed.

Christianity as Roman state religion[edit]

On 27 February 380, with the Edict of Thessalonica put forth under Theodosius I, Gratian, and Valentinian II, the Roman Empire officially adopted Trinitarian Christianity as its state religion. Prior to this date, Constantius II and Valens had personally favoured Arian or Semi-Arian forms of Christianity, but Valens' successor Theodosius I supported the Trinitarian doctrine as expounded in the Nicene Creed.

After its establishment, the Church adopted the same organisational boundaries as the Empire: geographical provinces, called dioceses, corresponding to imperial governmental territorial division. The bishops, who were located in major urban centres as per pre-legalisation tradition, thus oversaw each diocese. The bishop's location was his "seat", or "see". Among the sees, five came to hold special eminence: Rome, Constantinople, Jerusalem, Antioch, and Alexandria. The prestige of most of these sees depended in part on their apostolic founders, from whom the bishops were therefore the spiritual successors. Though the bishop of Rome was still held to be the First among equals, Constantinople was second in precedence as the new capital of the empire.

Theodosius I decreed that others not believing in the preserved "faithful tradition", such as the Trinity, were to be considered to be practitioners of illegal heresy,[29] and in 385, this resulted in the first case of capital punishment of a heretic, namely Priscillian.[30][31]

Nestorianism and the Sasanian Empire[edit]

During the early 5th century, the School of Edessa had taught a Christological perspective stating that Christ's divine and human nature were distinct persons. A particular consequence of this perspective was that Mary could not be properly called the mother of God but could only be considered the mother of Christ. The most widely known proponent of this viewpoint was the Patriarch of Constantinople Nestorius. Since referring to Mary as the mother of God had become popular in many parts of the Church this became a divisive issue.

The Roman Emperor Theodosius II called for the Council of Ephesus (431), with the intention of settling the issue. The councils ultimately rejected Nestorius' view. Many churches who followed the Nestorian viewpoint broke away from the Roman Church, causing a major schism. The Nestorian churches were persecuted, and many followers fled to the Sasanian Empire where they were accepted. The Sasanian (Persian) Empire had many Christian converts early in its history tied closely to the Syriac branch of Christianity. The Empire was officially Zoroastrian and maintained a strict adherence to this faith in part to distinguish itself from the religion of the Roman Empire (originally the pagan Roman religion and then Christianity). Christianity became tolerated in the Sasanian Empire, and as the Roman Empire increasingly exiled heretics during the 4th and 6th centuries, the Sasanian Christian community grew rapidly.[32] By the end of the 5th century, the Persian Church was firmly established and had become independent of the Roman Church. This church evolved into what is today known as the Church of the East.

In 451, the Council of Chalcedon was held to further clarify the Christological issues surrounding Nestorianism. The council ultimately stated that Christ's divine and human nature were separate but both part of a single entity, a viewpoint rejected by many churches who called themselves miaphysites. The resulting schism created a communion of churches, including the Armenian, Syrian, and Egyptian churches.[33] Though efforts were made at reconciliation in the next few centuries, the schism remained permanent, resulting in what is today known as Oriental Orthodoxy.

Monasticism[edit]

Monasticism is a form of asceticism whereby one renounces worldly pursuits and goes off alone as a hermit or joins a tightly organized community. It began early in the Church as a family of similar traditions, modelled upon Scriptural examples and ideals, and with roots in certain strands of Judaism. John the Baptist is seen as an archetypical monk, and monasticism was inspired by the organisation of the Apostolic community as recorded in Acts 2.

Eremetic monks, or hermits, live in solitude, whereas cenobitics live in communities, generally in a monastery, under a rule (or code of practice) and are governed by an abbot. Originally, all Christian monks were hermits, following the example of Anthony the Great. However, the need for some form of organised spiritual guidance lead Pachomius in 318 to organise his many followers in what was to become the first monastery. Soon, similar institutions were established throughout the Egyptian desert as well as the rest of the eastern half of the Roman Empire. Women were especially attracted to the movement.[34] Central figures in the development of monasticism were Basil the Great in the East and, in the West, Benedict, who created the famous Rule of Saint Benedict, which would become the most common rule throughout the Middle Ages and the starting point for other monastic rules.[35]

Early Middle Ages (476–799)[edit]

The transition into the Middle Ages was a gradual and localised process. Rural areas rose as power centres whilst urban areas declined. Although a greater number of Christians remained in the East (Greek areas), important developments were underway in the West (Latin areas) and each took on distinctive shapes. The bishops of Rome, the popes, were forced to adapt to drastically changing circumstances. Maintaining only nominal allegiance to the emperor, they were forced to negotiate balances with the "barbarian rulers" of the former Roman provinces. In the East, the Church maintained its structure and character and evolved more slowly.

Western missionary expansion[edit]

The stepwise loss of Western Roman Empire dominance, replaced with foederati and Germanic kingdoms, coincided with early missionary efforts into areas not controlled by the collapsing empire.[36] As early as in the 5th century, missionary activities from Roman Britain into the Celtic areas (Scotland, Ireland and Wales) produced competing early traditions of Celtic Christianity, that was later reintegrated under the Church in Rome. Prominent missionaries were Saints Patrick, Columba and Columbanus. The Anglo-Saxon tribes that invaded southern Britain some time after the Roman abandonment were initially pagan but were converted to Christianity by Augustine of Canterbury on the mission of Pope Gregory the Great. Soon becoming a missionary centre, missionaries such as Wilfrid, Willibrord, Lullus and Boniface converted their Saxon relatives in Germania.

The largely Christian Gallo-Roman inhabitants of Gaul (modern France) were overrun by the Franks in the early 5th century. The native inhabitants were persecuted until the Frankish King Clovis I converted from paganism to Roman Catholicism in 496. Clovis insisted that his fellow nobles follow suit, strengthening his newly established kingdom by uniting the faith of the rulers with that of the ruled.[37] After the rise of the Frankish Kingdom and the stabilizing political conditions, the Western part of the Church increased the missionary activities, supported by the Merovingian kingdom as a means to pacify troublesome neighbour peoples. After the foundation of a church in Utrecht by Willibrord, backlashes occurred when the pagan Frisian King Radbod destroyed many Christian centres between 716 and 719. In 717, the English missionary Boniface was sent to aid Willibrord, re-establishing churches in Frisia continuing missions in Germany.[37]

Byzantine Iconoclasm[edit]

Following a series of heavy military reverses against the Muslims, the Iconoclasm emerged in the early 8th century. In the 720s, the Byzantine Emperor Leo III the Isaurian banned the pictorial representation of Christ, saints, and biblical scenes. In the West, Pope Gregory III held two synods at Rome and condemned Leo's actions. The Byzantine Iconoclast Council, held at Hieria in 754, ruled that holy portraits were heretical.[38] The movement destroyed much of the Christian church's early artistic history. The iconoclastic movement was later defined as heretical in 787 under the Second Council of Nicaea (the seventh ecumenical council) but had a brief resurgence between 815 and 842.

High Middle Ages (800–1299)[edit]

Carolingian Renaissance[edit]

The Carolingian Renaissance was a period of intellectual and cultural revival of literature, arts, and scriptural studies during the late 8th and 9th centuries, mostly during the reigns of Charlemagne and Louis the Pious, Frankish rulers. To address the problems of illiteracy among clergy and court scribes, Charlemagne founded schools and attracted the most learned men from all of Europe to his court.

Growing tensions between East and West[edit]

Tensions in Christian unity started to become evident in the 4th century. Two basic problems were involved: the nature of the primacy of the bishop of Rome and the theological implications of adding a clause to the Nicene Creed, known as the filioque clause. These doctrinal issues were first openly discussed in Photius's patriarchate. The Eastern churches viewed Rome's understanding of the nature of episcopal power as being in direct opposition to the Church's essentially conciliar structure and thus saw the two ecclesiologies as mutually antithetical.[39]

The other major irritant to Eastern Christendom was the Western use of the Filioque clause—meaning "and the Son"—in the Nicene Creed . This too developed gradually and entered the Creed over time. The issue was the addition by the West of the Latin clause Filioque to the Creed, as in "the Holy Spirit... who proceeds from the Father and the Son", where the original Creed, sanctioned by the councils and still used today by the Eastern Orthodox, simply states "the Holy Spirit, the Lord and Giver of Life, who proceeds from the Father." The Eastern Church argued that the phrase had been added unilaterally and therefore illegitimately, since the East had never been consulted.[40] In addition to this ecclesiological issue, the Eastern Church also considered the Filioque clause unacceptable on dogmatic grounds.[41]

Photian schism[edit]

In the 9th century, a controversy arose between Eastern (Byzantine, Greek Orthodox) and Western (Latin, Roman Catholic) Christianity that was precipitated by the opposition of the Roman Pope John VII to the appointment by the Byzantine Emperor Michael III of Photios I to the position of patriarch of Constantinople. Photios was refused an apology by the pope for previous points of dispute between the East and West. Photios refused to accept the supremacy of the pope in Eastern matters or accept the Filioque clause. The Latin delegation at the council of his consecration pressed him to accept the clause in order to secure their support. The controversy also involved Eastern and Western ecclesiastical jurisdictional rights in the Bulgarian church. Photios did provide concession on the issue of jurisdictional rights concerning Bulgaria, and the papal legates made do with his return of Bulgaria to Rome. This concession, however, was purely nominal, as Bulgaria's return to the Byzantine rite in 870 had already secured for it an autocephalous church. Without the consent of Boris I of Bulgaria, the papacy was unable to enforce any of its claims.

East–West Schism (1054)[edit]

The East–West Schism, or Great Schism, separated the Church into Western (Latin) and Eastern (Greek) branches, i.e., Western Catholicism and Eastern Orthodoxy. It was the first major division since certain groups in the East rejected the decrees of the Council of Chalcedon (see Oriental Orthodoxy) and was far more significant. Though normally dated to 1054, the East–West Schism was actually the result of an extended period of estrangement between Latin and Greek Christendom over the nature of papal primacy and certain doctrinal matters like the filioque, but intensified by cultural and linguistic differences.

Monastic reform[edit]

From the 6th century, onward most of the monasteries in the West were of the Benedictine Order. Owing to the stricter adherence to a reformed Benedictine rule, the abbey of Cluny became the acknowledged leader of western monasticism from the later 10th century. Cluny created a large, federated order in which the administrators of subsidiary houses served as deputies of the abbot of Cluny and answered to him. The Cluniac spirit was a revitalising influence on the Norman church, at its height from the second half of the 10th century through the early 12th century.

The next wave of monastic reform came with the Cistercian Movement. The first Cistercian abbey was founded in 1098, at Cîteaux Abbey. The keynote of Cistercian life was a return to a literal observance of the Benedictine rule, rejecting the developments of the Benedictines. The most striking feature in the reform was the return to manual labour, and especially to field-work. Inspired by Bernard of Clairvaux, the primary builder of the Cistercians, they became the main force of technological diffusion in medieval Europe. By the end of the 12th century, the Cistercian houses numbered 500, and at its height in the 15th century the order claimed to have close to 750 houses. Most of these were built in wilderness areas, and played a major part in bringing such isolated parts of Europe into economic cultivation.

A third level of monastic reform was provided by the establishment of the Mendicant orders. Commonly known as friars, mendicants live under a monastic rule with traditional vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience, but they emphasise preaching, missionary activity, and education, in a secluded monastery. Beginning in the 12th century, the Franciscan order was instituted by the followers of Francis of Assisi, and thereafter the Dominican order was begun by St. Dominic.

Investiture Controversy[edit]

The Investiture Controversy, or Lay investiture controversy, was the most significant conflict between secular and religious powers in medieval Europe. It began as a dispute in the 11th century between the Holy Roman Emperor Henry IV and Pope Gregory VII concerning who would appoint bishops (investiture). The end of lay investiture threatened to undercut the power of the Empire and the ambitions of noblemen. Bishoprics being merely lifetime appointments, a king could better control their powers and revenues than those of hereditary noblemen. Even better, he could leave the post vacant and collect the revenues, theoretically in trust for the new bishop, or give a bishopric to pay a helpful noble. The Church wanted to end lay investiture to end this and other abuses, to reform the episcopate and provide better pastoral care. Pope Gregory VII issued the Dictatus Papae, which declared that the pope alone could appoint bishops. Henry IV's rejection of the decree led to his excommunication and a ducal revolt. Eventually Henry received absolution after dramatic public penance, though the Great Saxon Revolt and conflict of investiture continued.

A similar controversy occurred in England between King Henry I and St. Anselm, Archbishop of Canterbury, over investiture and episcopal vacancy. The English dispute was resolved by the Concordat of London, 1107, where the king renounced his claim to invest bishops but continued to require an oath of fealty. This was a partial model for the Concordat of Worms (Pactum Calixtinum), which resolved the Imperial investiture controversy with a compromise that allowed secular authorities some measure of control but granted the selection of bishops to their cathedral canons. As a symbol of the compromise, both ecclesiastical and lay authorities invested bishops with respectively, the staff and the ring.

Crusades[edit]

Generally, the Crusades refer to the campaigns in the Holy Land against Muslim forces sponsored by the papacy. There were other crusades against Islamic forces in southern Spain, southern Italy, and Sicily, as well as the campaigns of Teutonic Knights against pagan strongholds in north-eastern Europe. A few crusades were waged within Christendom against groups that were considered heretical and schismatic.

The Holy Land had been part of the Roman Empire, and thus Byzantine Empire, until the Islamic conquests of the 7th and 8th centuries. Thereafter, Christians had generally been permitted to visit the sacred places in the Holy Land until 1071, when the Seljuk Turks closed Christian pilgrimages and assailed the Byzantines, defeating them at the Battle of Manzikert. Emperor Alexius I asked for aid from Pope Urban II against Islamic aggression. He probably expected money from the pope for the hiring of mercenaries. Instead, Urban II called upon the knights of Christendom in a speech made at the Council of Clermont on 27 November 1095, combining the idea of pilgrimage to the Holy Land with that of waging a holy war against infidels.

The First Crusade captured Antioch in 1099 and then Jerusalem. The Second Crusade occurred in 1145 when Edessa was retaken by Islamic forces. Jerusalem was held until 1187 and the Third Crusade, famous for the battles between Richard the Lionheart and Saladin. The Fourth Crusade, begun by Innocent III in 1202, intended to retake the Holy Land but was soon subverted by Venetians who used the forces to sack the Christian city of Zara.[42] When the crusaders arrived in Constantinople, they sacked the city and other parts of Asia Minor and established the Latin Empire of Constantinople in Greece and Asia Minor. This was effectively the last crusade sponsored by the papacy, with later crusades being sponsored by individuals.[42]

Jerusalem was held by the crusaders for nearly a century, while other strongholds in the Near East remained in Christian possession much longer. The crusades in the Holy Land ultimately failed to establish permanent Christian kingdoms. Islamic expansion into Europe remained a threat for centuries, culminating in the campaigns of Suleiman the Magnificent in the 16th century.[42] Crusades in southern Spain, southern Italy, and Sicily eventually lead to the demise of Islamic power in Europe.[42] Teutonic Knights expanded Christian domains in Eastern Europe, and the much less frequent crusades within Christendom, such as the Albigensian Crusade, achieved their goal of maintaining doctrinal unity.[42]

Medieval Inquisition[edit]

The Medieval Inquisition was a series of inquisitions (Roman Catholic Church bodies charged with suppressing heresy) from around 1184, including the Episcopal Inquisition (1184–1230s) and later the Papal Inquisition (1230s). It was in response to movements within Europe considered apostate or heretical to Western Catholicism, in particular the Cathars and the Waldensians in southern France and northern Italy. These were the first inquisition movements of many that would follow. The inquisitions in combination with the Albigensian Crusade were fairly successful in ending heresy. Historian Thomas F. Madden has written about popular myths regarding the inquisition.[43]

Spread of Christianity[edit]

Early evangelisation in Scandinavia was begun by Ansgar, Archbishop of Bremen, "Apostle of the North". Ansgar, a native of Amiens, was sent with a group of monks to Jutland in around 820 at the time of the pro-Christian King Harald Klak. The mission was only partially successful, and Ansgar returned two years later to Germany, after Harald had been driven out of his kingdom. In 829, Ansgar went to Birka on Lake Mälaren, Sweden, with his aide friar Witmar, and a small congregation was formed in 831 which included the king's steward Hergeir. Conversion was slow, however, and most Scandinavian lands were only completely Christianised at the time of rulers such as Saint Canute IV of Denmark and Olaf I of Norway in the years following AD 1000.

The Christianisation of the Slavs was initiated by one of Byzantium's most learned churchmen—the patriarch Photios I of Constantinople. The Byzantine Emperor Michael III chose Cyril and Methodius in response to a request from King Rastislav of Moravia, who wanted missionaries that could minister to the Moravians in their own language. The two brothers spoke the local Slavonic vernacular and translated the Bible and many of the prayer books.[44] As the translations prepared by them were copied by speakers of other dialects, the hybrid literary language Old Church Slavonic was created, which later evolved into Church Slavonic and is the common liturgical language still used by the Russian Orthodox Church and other Slavic Orthodox Christians. Methodius went on to convert the Serbs.[45]

Bulgaria was a pagan country since its establishment in 681 until 864 when Boris I converted to Christianity. The reasons for that decision were complex; the most important factors were that Bulgaria was situated between two powerful Christian empires, Byzantium and East Francia; Christian doctrine particularly favoured the position of the monarch as God's representative on Earth, while Boris also saw it as a way to overcome the differences between Bulgars and Slavs.[46][47] Bulgaria was officially recognised as a patriarchate by Constantinople in 927, Serbia in 1346, and Russia in 1589. All of these nations, however, had been converted long before these dates.

Late Middle Ages and the early Renaissance (1300–1520)[edit]

Avignon Papacy and Western Schism[edit]

The Avignon Papacy, sometimes referred to as the Babylonian Captivity, was a period from 1309 to 1378 during which seven popes resided in Avignon, in modern-day France.[48] In 1309, Pope Clement V moved to Avignon in southern France. Confusion and political animosity waxed, as the prestige and influence of Rome waned without a resident pontiff. Troubles reached their peak in 1378 when Gregory XI died while visiting Rome. A papal conclave met in Rome and elected Urban VI, an Italian. Urban soon alienated the French cardinals, and they held a second conclave electing Robert of Geneva to succeed Gregory XI, beginning the Western Schism.

Criticism of Church corruption[edit]

John Wycliffe, an English scholar and alleged heretic best known for denouncing the corruptions of the Church, was a precursor of the Protestant Reformation. He emphasized the supremacy of the Bible and called for a direct relationship between man and God, without interference by priests and bishops. His followers played a role in the English Reformation.[49][50] Jan Hus, a Czech theologian in Prague, was influenced by Wycliffe and spoke out against the corruptions he saw in the Church. He was a forerunner of the Protestant Reformation, and his legacy has become a powerful symbol of Czech culture in Bohemia.[51]

Italian Renaissance[edit]

The Renaissance was a period of great cultural change and achievement, marked in Italy by a classical orientation and an increase of wealth through mercantile trade. The city of Rome, the papacy, and the papal states were all affected by the Renaissance. On the one hand, it was a time of great artistic patronage and architectural magnificence, where the Church commissioned such artists as Michelangelo, Brunelleschi, Bramante, Raphael, Fra Angelico, Donatello, and da Vinci. On the other hand, wealthy Italian families often secured episcopal offices, including the papacy, for their own members, some of whom were known for immorality, such as Alexander VI and Sixtus IV.

In addition to being the head of the Church, the pope became one of Italy's most important secular rulers, and pontiffs such as Julius II often waged campaigns to protect and expand their temporal domains. Furthermore, the popes, in a spirit of refined competition with other Italian lords, spent lavishly both on private luxuries but also on public works, repairing or building churches, bridges, and a magnificent system of aqueducts in Rome that still function today.

Fall of Constantinople[edit]

In 1453, Constantinople fell to the Ottoman Empire. Eastern Christians fleeing Constantinople, and the Greek manuscripts they carried with them, is one of the factors that prompted the literary renaissance in the West at about this time. The Ottoman government followed Islamic law when dealing with the conquered Christian population. Christians were officially tolerated as people of the Book. As such, the Church's canonical and hierarchical organisation were not significantly disrupted, and its administration continued to function. One of the first things that Mehmet the Conqueror did was to allow the Church to elect a new patriarch, Gennadius Scholarius. However, these rights and privileges, including freedom of worship and religious organisation, were often established in principle but seldom corresponded to reality. Christians were viewed as second-class citizens, and the legal protections they depended upon were subject to the whims of the sultan and the sublime porte.[52][53] The Hagia Sophia and the Parthenon, which had been Christian churches for nearly a millennium, were converted into mosques. Violent persecutions of Christians were common and reached their climax in the Armenian, Assyrian, and Greek genocides.

Early modern period (c. 1500 – c. 1750)[edit]

Protestant Reformation[edit]

In the early 16th century, attempts were made by the theologians Martin Luther and Huldrych Zwingli, along with many others, to reform the Church. They considered the root of corruptions to be doctrinal, rather than simply a matter of moral weakness or lack of ecclesiastical discipline, and thus advocated for God's autonomy in redemption, and against voluntaristic notions that salvation could be earned by people. The Reformation is usually considered to have started with the publication of the Ninety-five Theses by Luther in 1517, although there was no schism until the 1521 Diet of Worms. The edicts of the Diet condemned Luther and officially banned citizens of the Holy Roman Empire from defending or propagating his ideas.[54]

The word Protestant is derived from the Latin protestatio, meaning declaration, which refers to the letter of protestation by Lutheran princes against the decision of the Diet of Speyer in 1529, which reaffirmed the edict of the Diet of Worms ordering the seizure of all property owned by persons guilty of advocating Lutheranism.[55] The term "Protestant" was not originally used by Reformation era leaders; instead, they called themselves "evangelical", emphasising the "return to the true gospel (Greek: euangelion)."[56]

Early protest was against corruptions such as simony, the holding of multiple church offices by one person at the same time, episcopal vacancies, and the sale of indulgences. The Protestant position also included sola scriptura, sola fide, the priesthood of all believers, Law and Gospel, and the two kingdoms doctrine. The three most important traditions to emerge directly from the Protestant Reformation were the Lutheran, Reformed, and Anglican traditions, though the latter group identifies as both "Reformed" and "Catholic", and some subgroups reject the classification as "Protestant."

Counter-Reformation[edit]

The Counter-Reformation was the response of the Catholic Church to the Protestant Reformation. In terms of meetings and documents, it consisted of the Confutatio Augustana, the Council of Trent, the Roman Catechism, and the Defensio Tridentinæ fidei. In terms of politics, the Counter-Reformation included heresy trials, the exiling of Protestant populations from Catholic lands, the seizure of children from their Protestant parents for institutionalized Catholic upbringing, a series of wars, the Index Librorum Prohibitorum (the list of prohibited books), and the Spanish Inquisition.

Although Protestants were excommunicated in an attempt to reduce their influence within the Catholic Church, at the same time they were persecuted during the Counter-Reformation, prompting some to live as crypto-Protestants (also termed Nicodemites, against the urging of John Calvin who urged them to live their faith openly.[57] Crypto-Protestants were documented as late as the 19th century in Latin America.[58]

The Council of Trent (1545–1563), initiated by Pope Paul III addressed issues of certain ecclesiastical corruptions such as simony, absenteeism, nepotism, the holding of multiple church offices by one person, and other abuses, as well as the reassertion of traditional practices and the dogmatic articulation of the traditional doctrines of the Church, such as the episcopal structure, clerical celibacy, the seven Sacraments, transubstantiation (the belief that during mass the consecrated bread and wine truly become the body and blood of Christ), the veneration of relics, icons, and saints (especially the Blessed Virgin Mary), the necessity of both faith and good works for salvation, the existence of purgatory and the issuance (but not the sale) of indulgences. In other words, all Protestant doctrinal objections and changes were uncompromisingly rejected. The Council also fostered an interest in education for parish priests to increase pastoral care. Milan's Archbishop Saint Charles Borromeo set an example by visiting the remotest parishes and instilling high standards.

English Reformation[edit]

Unlike other reform movements, the English Reformation began by royal influence. Henry VIII considered himself a thoroughly Catholic king, and in 1521 he defended the papacy against Luther in a book he commissioned entitled, The Defence of the Seven Sacraments, for which Pope Leo X awarded him the title Fidei Defensor (Defender of the Faith). However, the king came into conflict with the papacy when he wished to annul his marriage with Catherine of Aragon, for which he needed papal sanction. Catherine, among many other noble relations, was the aunt of Emperor Charles V, the papacy's most significant secular supporter. The ensuing dispute eventually lead to a break from Rome and the declaration of the King of England as head of the English Church. Consequently, England experienced periods of reform and also Counter-Reformation. Monarchs such as Edward VI, Lady Jane Grey, Mary I, Elizabeth I, and Archbishops of Canterbury such as Thomas Cranmer and William Laud pushed the Church of England in different directions over the course of only a few generations. What emerged was the Elizabethan Religious Settlement and a state church that considered itself both "Reformed" and "Catholic" but not "Roman" (and hesitated from the title "Protestant"), and other unofficial more radical movements such as the Puritans. In terms of politics, the English Reformation included heresy trials, the exiling of Catholic populations to Spain and other Catholic lands, and censorship and prohibition of books.[59]

Catholic Reformation[edit]

Simultaneous to the Counter-Reformation, the Catholic Reformation consisted of improvements in art and culture, anti-corruption measures, the founding of the Jesuits, the establishment of seminaries, a reassertion of traditional doctrines and the emergence of new religious orders aimed at both moral reform and new missionary activity. Also part of this was the development of new yet orthodox forms of spirituality, such as that of the Spanish mystics and the French school of spirituality.

The papacy of St. Pius V was known not only for its focus on halting heresy and worldly abuses within the Church, but also for its focus on improving popular piety in a determined effort to stem the appeal of Protestantism. Pius began his pontificate by giving large alms to the poor, charity, and hospitals, and the pontiff was known for consoling the poor and sick as well as supporting missionaries. The activities of these pontiffs coincided with a rediscovery of the ancient Christian catacombs in Rome. As Diarmaid MacCulloch states, "Just as these ancient martyrs were revealed once more, Catholics were beginning to be martyred afresh, both in mission fields overseas and in the struggle to win back Protestant northern Europe: the catacombs proved to be an inspiration for many to action and to heroism."[60]

Catholic missions were carried to new places beginning with the new Age of Discovery, and the Roman Catholic Church established missions in the Americas.

Trial of Galileo[edit]

The Galileo affair, in which Galileo Galilei came into conflict with the Roman Catholic Church over his support of Copernican astronomy, is often considered a defining moment in the history of the relationship between religion and science. In 1610, Galileo published his Sidereus Nuncius (Starry Messenger), describing the surprising observations that he had made with the new telescope. These and other discoveries exposed major difficulties with the understanding of the Heavens that had been held since antiquity, and raised new interest in radical teachings such as the heliocentric theory of Copernicus. In reaction, many scholars maintained that the motion of the Earth and immobility of the Sun were heretical, as they contradicted some accounts given in the Bible as understood at that time. Galileo's part in the controversies over theology, astronomy and philosophy culminated in his trial and sentencing in 1633, on a grave suspicion of heresy.

Puritans in North America[edit]

The most famous colonisation by Protestants in the New World was that of English Puritans in North America. Unlike the Spanish or French, the English colonists made surprisingly little effort to evangelise the native peoples.[61] The Puritans, or Pilgrims, left England so that they could live in an area with Puritanism established as the exclusive civic religion. Though they had left England because of the suppression of their religious practice, most Puritans had thereafter originally settled in the Low Countries but found the licentiousness there, where the state hesitated from enforcing religious practice, as unacceptable, and thus they set out for the New World and the hopes of a Puritan utopia.

Late modern period (c. 1750 – c. 1945)[edit]

Revivalism[edit]

Revivalism refers to the Calvinist and Wesleyan revival, called the Great Awakening in North America, which saw the development of evangelical Congregationalist, Presbyterian, Baptist, and new Methodist churches.

Great Awakenings[edit]

The First Great Awakening was a wave of religious enthusiasm among Protestants in the American colonies c. 1730–1740, emphasising the traditional Reformed virtues of Godly preaching, rudimentary liturgy, and a deep sense of personal guilt and redemption by Christ Jesus. Historian Sydney E. Ahlstrom saw it as part of a "great international Protestant upheaval" that also created pietism in Germany, the Evangelical Revival, and Methodism in England.[62] It centred on reviving the spirituality of established congregations and mostly affected Congregational, Presbyterian, Dutch Reformed, German Reformed, Baptist, and Methodist churches, while also spreading within the slave population. The Second Great Awakening (1800–1830s), unlike the first, focused on the unchurched and sought to instill in them a deep sense of personal salvation as experienced in revival meetings. It also sparked the beginnings of groups such as the Mormons, the Restoration Movement and the Holiness movement. The Third Great Awakening began from 1857 and was most notable for taking the movement throughout the world, especially in English speaking countries. The final group to emerge from the "great awakenings" in North America was Pentecostalism, which had its roots in the Methodist, Wesleyan, and Holiness movements, and began in 1906 on Azusa Street in Los Angeles. Pentecostalism would later lead to the Charismatic movement.

Restorationism[edit]

Restorationism refers to the belief that a purer form of Christianity should be restored using the early church as a model.[63]:635[64]:217 In many cases, restorationist groups believed that contemporary Christianity, in all its forms, had deviated from the true, original Christianity, which they then attempted to "reconstruct", often using the Book of Acts as a "guidebook" of sorts. Restorationists do not usually describe themselves as "reforming" a Christian church continuously existing from the time of Jesus, but as restoring the Church that they believe was lost at some point. "Restorationism" is often used to describe the Stone-Campbell Restoration Movement.

The term "restorationist" is also used to describe the Jehovah's Witness movement, founded in the late 1870s by Charles Taze Russell. The term can also be used to describe the Latter Day Saint movement, including The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church), the Community of Christ and numerous other Latter Day Saints sects. Latter Day Saints, also known as Mormons, believe that Joseph Smith was chosen to restore the original organization established by Jesus, now "in its fullness", rather than to reform the church.[65][66]

Eastern Orthodoxy[edit]

The Russian Orthodox Church held a privileged position in the Russian Empire, expressed in the motto of the late empire from 1833: Orthodoxy, Autocracy, and Populism. Nevertheless, the Church reform of Peter I in the early 18th century had placed the Orthodox authorities under the control of the tsar. An ober-procurator appointed by the tsar ran the committee which governed the Church between 1721 and 1918: the Most Holy Synod. The Church became involved in the various campaigns of russification,[67] and was accused of involvement in Russian anti-semitism,[68] despite the lack of an official position on Judaism as such.[69]

The Bolsheviks and other Russian revolutionaries saw the Church, like the tsarist state, as an enemy of the people. Criticism of atheism was strictly forbidden and sometimes lead to imprisonment.[70][71][72] Some actions against Orthodox priests and believers included torture, being sent to prison camps, labour camps or mental hospitals, as well as execution.[73][74]

In the first five years after the Bolshevik revolution, 28 bishops and 1,200 priests were executed.[75] This included people like the Grand Duchess Elizabeth Fyodorovna who was at this point a monastic. Along with her murder was Grand Duke Sergei Mikhailovich Romanov; the Princes Ioann Konstantinvich, Konstantin Konstantinovich, Igor Konstantinovich and Vladimir Pavlovich Paley; Grand Duke Sergei's secretary, Fyodor Remez; and Varvara Yakovleva, a sister from the Grand Duchess Elizabeth's convent.

Trends in Christian theology[edit]

Liberal Christianity, sometimes called liberal theology, is an umbrella term covering diverse, philosophically informed religious movements and moods within late 18th, 19th and 20th-century Christianity. The word "liberal" in liberal Christianity does not refer to a leftist political agenda or set of beliefs, but rather to the freedom of dialectic process associated with continental philosophy and other philosophical and religious paradigms developed during the Age of Enlightenment.

Fundamentalist Christianity is a movement that arose mainly within British and American Protestantism in the late 19th century and early 20th century in reaction to modernism and certain liberal Protestant groups that denied doctrines considered fundamental to Christianity yet still called themselves "Christian." Thus, fundamentalism sought to re-establish tenets that could not be denied without relinquishing a Christian identity, the "fundamentals": inerrancy of the Bible, Sola Scriptura, the Virgin Birth of Jesus, the doctrine of substitutionary atonement, the bodily Resurrection of Jesus, and the imminent return of Jesus Christ.

Under Nazism[edit]

The position of Christians affected by Nazism is highly complex. Regarding the matter, historian Derek Holmes writes, "There is no doubt that the Catholic districts, resisted the lure of National Socialism [Nazism] far better than the Protestant ones."[76] Pope Pius XI declared – Mit brennender Sorge – that Fascist governments had hidden "pagan intentions" and expressed the irreconcilability of the Catholic position and totalitarian fascist state worship, which placed the nation above God, fundamental human rights, and dignity. His declaration that "Spiritually, [Christians] are all Semites" prompted the Nazis to give him the title "Chief Rabbi of the Christian World."[77]

Catholic priests were executed in concentration camps alongside Jews; for example, 2,600 Catholic priests were imprisoned in Dachau, and 2,000 of them were executed. A further 2,700 Polish priests were executed (a quarter of all Polish priests), and 5,350 Polish nuns were either displaced, imprisoned, or executed.[78] Many Catholic laymen and clergy played notable roles in sheltering Jews during the Holocaust, including Pope Pius XII. The head rabbi of Rome became a Catholic in 1945, and in honour of the actions the pope undertook to save Jewish lives, he took the name Eugenio (the pope's first name).[79] A former Israeli consul in Italy claimed: "The Catholic Church saved more Jewish lives during the war than all the other churches, religious institutions, and rescue organisations put together."[80]

The relationship between Nazism and Protestantism, especially the German Lutheran Church, was complex. Though many[81] Protestant church leaders in Germany supported the Nazis' growing anti-Jewish activities, some such as Dietrich Bonhoeffer (a Lutheran pastor) were strongly opposed to the Nazis. Bonhoeffer was later found guilty in the conspiracy to assassinate Hitler and executed.

Contemporary Christianity[edit]

Second Vatican Council[edit]

On 11 October 1962, Pope John XXIII opened the Second Vatican Council, the 21st ecumenical council of the Catholic Church. The council was "pastoral" in nature, emphasising and clarifying already defined dogma, revising liturgical practices, and providing guidance for articulating traditional Church teachings in contemporary times. The council is perhaps best known for its instructions that the Mass may be celebrated in the vernacular as well as in Latin.

Ecumenism[edit]

Ecumenism broadly refers to movements between Christian groups to establish a degree of unity through dialogue. Ecumenism is derived from Greek οἰκουμένη (oikoumene), which means "the inhabited world", but more figuratively something like "universal oneness." The movement can be distinguished into Catholic and Protestant movements, with the latter characterised by a redefined ecclesiology of "denominationalism" (which the Catholic Church, among others, rejects).

Over the last century, moves have been made to reconcile the schism between the Catholic Church and the Eastern Orthodox churches. Although progress has been made, concerns over papal primacy and the independence of the smaller Orthodox churches has blocked a final resolution of the schism. On 30 November 1894, Pope Leo XIII published Orientalium Dignitas. On 7 December 1965, a Joint Catholic-Orthodox Declaration of Pope Paul VI and the Ecumenical Patriarch Athenagoras I was issued lifting the mutual excommunications of 1054.

Some of the most difficult questions in relations with the ancient Eastern Churches concern some doctrine (i.e. filioque, scholasticism, functional purposes of asceticism, the essence of God, Hesychasm, Fourth Crusade, establishment of the Latin Empire, Uniatism to note but a few) as well as practical matters such as the concrete exercise of the claim to papal primacy and how to ensure that ecclesiastical union would not mean mere absorption of the smaller Churches by the Latin component of the much larger Catholic Church (the most numerous single religious denomination in the world), and the stifling or abandonment of their own rich theological, liturgical and cultural heritage.

With respect to Catholic relations with Protestant communities, certain commissions were established to foster dialogue and documents have been produced aimed at identifying points of doctrinal unity, such as the Joint Declaration on the Doctrine of Justification produced with the Lutheran World Federation in 1999.

Pentecostal movement[edit]

In reaction to these developments, Christian fundamentalism was a movement to reject the radical influences of philosophical humanism, as this was affecting the Christian religion. Especially targeting critical approaches to the interpretation of the Bible, and trying to blockade the inroads made into their churches by atheistic scientific assumptions, the fundamentalists began to appear in various denominations as numerous independent movements of resistance to the drift away from historic Christianity. Over time, the Fundamentalist Evangelical movement has divided into two main wings, with the label Fundamentalist following one branch, while Evangelical has become the preferred banner of the more moderate movement. Although both movements primarily originated in the English-speaking world, the majority of Evangelicals now live elsewhere in the world.

Ecumenism within Protestantism[edit]

Ecumenical movements within Protestantism have focused on determining a list of doctrines and practices essential to being Christian and thus extending to all groups which fulfill these basic criteria a (more or less) co-equal status, with perhaps one's own group still retaining a "first among equal" standing. This process involved a redefinition of the idea of "the Church" from traditional theology. This ecclesiology, known as denominationalism, contends that each group (which fulfills the essential criteria of "being Christian") is a sub-group of a greater "Christian Church", itself a purely abstract concept with no direct representation, i.e., no group, or "denomination", claims to be "the Church." This ecclesiology is at variance with other groups that indeed consider themselves to be "the Church." The "essential criteria" generally consist of belief in the Trinity, belief that Jesus Christ is the only way to have forgiveness and eternal life, and that Jesus died and rose again bodily.

See also[edit]

- Christ myth theory

- Christian anarchism

- Christianity and Paganism

- Christianization

- History of Christian theology

- History of the Eastern Orthodox Church

- History of Oriental Orthodoxy

- History of Protestantism

- History of the Roman Catholic Church

- Rise of Christianity during the Fall of Rome

- Role of the Christian Church in civilization

- Timeline of Christian missions

- Timeline of Christianity

- Timeline of the Roman Catholic Church

Notes[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ Adherents.com, Religions by Adherents

- ^ BBC documentary: A History of Christianity by Diarmaid MacCulloch, Oxford University

- ^ Schaff, Philip (1998) [1858-1890]. History of the Christian Church. 2: Ante-Nicene Christianity. A.D. 100-325. Christian Classics Ethereal Library. ISBN 9781610250412. Retrieved 13 October 2019.

The ante-Nicene age... is the natural transition from the apostolic age to the Nicene age....

- ^ "The figure (…) is an allegory of Christ as the shepherd" André Grabar, Christian iconography, a study of its origins, ISBN 0-691-01830-8

- ^ On the Creeds, see Oscar Cullmann, The Earliest Christian Confessions, trans. J. K. S. Reid (London: Lutterworth, 1949)

- ^ Michael Whitby, et al. eds. Christian Persecution, Martyrdom and Orthodoxy (2006) online edition

- ^ Robert Michael (2005). A Concise History of American Antisemitism. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 101.

- ^ Stark, Rodney (9 May 1997). The Rise of Christianity. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-067701-5. Retrieved 28 October 2012.

- ^ Philip Carrington, The Early Christian Church (2 vol. 1957) online edition vol 1; online edition vol 2

- ^ Siker (2000). Pp 233–35.

- ^ Bauer, Walter (1971). Orthodoxy and Heresy in Earliest Christianity. ISBN 0-8006-1363-5.

- ^ Pagels, Elaine (1979). The Gnostic Gospels. ISBN 0-679-72453-2.

- ^ Ehrman, Bart D. (2003). Lost Christianities: The Battles for Scripture and the Faiths We Never Knew. New York: Oxford. ISBN 0-19-514183-0.

- ^ Everett Ferguson, "Factors leading to the Selection and Closure of the New Testament Canon", in The Canon Debate. eds. L. M. McDonald & J. A. Sanders (Hendrickson, 2002) pp. 302–303; cf. Justin Martyr, First Apology 67.3

- ^ Both points taken from Mark A. Noll's Turning Points, (Baker Academic, 1997) pp. 36–37

- ^ H. J. De Jonge, "The New Testament Canon", in The Biblical Canons. eds. de Jonge & J. M. Auwers (Leuven University Press, 2003) p. 315

- ^ F. F. Bruce, The Canon of Scripture (Intervarsity Press, 1988) p. 215

- ^ The Cambridge History of the Bible (volume 1) eds. P. R. Ackroyd and C. F. Evans (Cambridge University Press, 1970) p. 305

- ^ "The earliest Christian images appeared somewhere about the year 200." Andre Grabar, p. 7

- ^ a b Andre Grabar, p. 7

- ^ Martin, D. 2010. "The "Afterlife" of the New Testament and Postmodern Interpretation Archived 2016-06-08 at the Wayback Machine (lecture transcript Archived 2016-08-12 at the Wayback Machine). Yale University.

- ^ Gaddis, Michael (2005). There Is No Crime for Those Who Have Christ: Religious Violence in the Christian Roman Empire. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-24104-5.

- ^ "Persecution in the Early Church". Religion Facts. Retrieved 26 March 2014.

- ^ R. Gerberding and J. H. Moran Cruz, Medieval Worlds (New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 2004) p. 55

- ^ R. Gerberding and J. H. Moran Cruz, Medieval Worlds (New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 2004) pp. 55–56

- ^ Richards, Jeffrey. The Popes and the Papacy in the Early Middle Ages 476–752 (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1979) pp. 14–15

- ^ Ricciotti 1999

- ^ Padberg 1998, 26

- ^ It is our desire that all the various nations... should continue to profess that religion which... has been preserved by faithful tradition, and which is now professed by the Pontiff Damasus and by Peter, Bishop of Alexandria, a man of apostolic holiness. According to the apostolic teaching... let us believe in the one deity of the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit, in equal majesty and in a holy Trinity. ...others... shall be branded... heretics, and shall not presume to give to their conventicles the name of churches. —Henry Bettenson, ed., Documents of the Christian Church, (London: Oxford University Press, 1943), p. 31

- ^ Halsall, Paul (June 1997). "Theodosian Code XVI.i.2". Medieval Sourcebook: Banning of Other Religions. Fordham University. Retrieved 23 November 2006.

- ^ "Lecture 27: Heretics, Heresies and the Church". 2009. Retrieved 24 April 2010. Review of Church policies towards heresy, including capital punishment (see Synod at Saragossa).

- ^ Culture and customs of Iran, p. 61

- ^ Bussell (1910), p. 346.

- ^ Jeffrey F. Hamburger et al. Crown and Veil: Female Monasticism from the Fifth to the Fifteenth Centuries (2008)

- ^ Marilyn Dunn, Emergence of Monasticism: From the Desert Fathers to the Early Middle Ages (2003)

- ^ Kenneth Scott Latourette, A history of the expansion of Christianity: vol. 2, The thousand years of uncertainty: A.D. 500 – A.D. 1500

- ^ a b Janet L. Nelson, The Frankish world, 750–900 (1996)

- ^ Epitome, Iconoclast Council at Hieria, 754

- ^ Ware, Kallistos (1995). The Orthodox Church London. St. Vladimir's Seminary Press. ISBN 978-0-913836-58-3.

- ^ History of Russian Philosophy by Nikolai Lossky ISBN 978-0-8236-8074-0 Quoting Aleksey Khomyakov p. 87.

- ^ The Mystical Theology of the Eastern Church by Vladimir Lossky, SVS Press, 1997. (ISBN 0-913836-31-1) James Clarke & Co Ltd, 1991. (ISBN 0-227-67919-9)

- ^ a b c d e For such an analysis, see Brian Tierney and Sidney Painter, Western Europe in the Middle Ages 300–1475. 6th ed. (McGraw-Hill 1998)

- ^ "The Real Inquisition: Investigating the popular myth". Archived from the original on 31 July 2010. Retrieved 6 April 2013.

- ^ "Sts. Cyril and Methodius". Pravmir. Retrieved 31 August 2017.

- ^ "From Eastern Roman to Byzantine: transformation of Roman culture (500–800)". Indiana University Northwest. Retrieved 31 August 2017.

- ^ Andreev, J., The Bulgarian Khans and Tsars, Veliko Tarnovo, 1996, pp. 73–74

- ^ Fine, The Early Medieval Balkans. A Critical Survey from the Sixth to the Late Twelfth Century., 1983, p. 118

- ^ Morris, Colin, The papal monarchy: the Western church from 1050 to 1250 , (Oxford University Press, 2001), 271.

- ^ G. R. Evans, John Wyclif: Myth & Reality (2006)

- ^ Shannon McSheffrey, Lollards of Coventry, 1486–1522 (2003)

- ^ Thomas A. Fudge, Jan Hus: Religious Reform and Social Revolution in Bohemia (2010)

- ^ The Australian Institute for Holocaust and Genocide Studies Archived 7 June 2007 at the Wayback Machine The New York Times.

- ^ http://www.helleniccomserve.com/pdf/BlkBkPontusPrinceton.pdf

- ^ Fahlbusch, Erwin, and Bromiley, Geoffrey William, The Encyclopedia of Christianity, Volume 3. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Eerdmans, 2003. p. 362.

- ^ Definition of Protestantism at the Episcopal Church website Archived 15 August 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ MacCulloch, Diarmaid, The Reformation: A History (New York: Penguin Books, 2004) p. xx

- ^ Eire, Carlos M. N. "Calvin and Nicodemism: A Reappraisal". Sixteenth Century Journal X:1, 1979.

- ^ Martínez Fernández, Luis (2000). "Crypto-Protestants and Pseudo-Catholics in the Nineteenth-Century Hispanic Caribbean". Journal of Ecclesiastical History. 51 (2): 347–365.

- ^ Literature and censorship in Renaissance England, Andrew Hadfield, Palgrave Books, 2001.

- ^ MacCulloch, Diarmaid, The Reformation: A History (New York: Penguin Books, 2004) p. 404

- ^ MacCulloch, Diarmaid, The Reformation: A History (New York: Penguin Books, 2004) p. 540

- ^ Sydney E. Ahlstrom, A Religious History of the American People. (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1972) p. 263

- ^ Douglas Allen Foster and Anthony L. Dunnavant, The Encyclopedia of the Stone-Campbell Movement: Christian Church (Disciples of Christ), Christian Churches/Churches of Christ, Churches of Christ, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2004, ISBN 978-0-8028-3898-8, 854 pages, entry on Restoration, Historical Models of

- ^ Gerard Mannion and Lewis S. Mudge, The Routledge companion to the Christian church, Routledge, 2008, ISBN 978-0-415-37420-0, 684 pages

- ^ Roberts, B.H, ed. (1904), History of the Church, 3, Salt Lake City, Utah: Deseret News, ISBN 1-152-94824-5

- ^ Doctrine and Covenants (LDS Church edition) 21:11 (Apr. 1830); 42:78 (Feb. 1831); 107:59 (Mar. 1835).

- ^ Natalia Shlikhta (2004) "'Greek Catholic'–'Orthodox'–'Soviet': a symbiosis or a conflict of identities?" in Religion, State & Society, Volume 32, Number 3 (Routledge)

- ^ Shlomo Lambroza, John D. Klier (2003) Pogroms: Anti-Jewish Violence in Modern Russian History (Cambridge University Press)

- ^ "Jewish-Christian Relations"

- ^ Sermons to young people by Father George Calciu-Dumitreasa. Given at the Chapel of the Romanian Orthodox Church Seminary, The Word online. Bucharest http://www.orthodoxresearchinstitute.org/resources/sermons/calciu_christ_calling.htm

- ^ President of Lithuania: Prisoner of the Gulag a Biography of Aleksandras Stulginskis by Afonsas Eidintas Genocide and Research Centre of Lithuania ISBN 9789986757412 p. 23 "As early as August 1920 Lenin wrote to E. M. Skliansky, President of the Revolutionary War Soviet: "We are surrounded by the greens (we pack it to them), we will move only about 10–20 versty and we will choke by hand the bourgeoisie, the clergy and the landowners. There will be an award of 100,000 rubles for each one hanged." He was speaking about the future actions in the countries neighboring Russia.

- ^ Christ Is Calling You : A Course in Catacomb Pastorship by Father George Calciu Published by Saint Hermans Press April 1997 ISBN 978-1-887904-52-0

- ^ Father Arseny 1893–1973 Priest, Prisoner, Spiritual Father. Introduction pp. vi–1. St Vladimir's Seminary Press ISBN 0-88141-180-9

- ^ The Washington Post Anti-Communist Priest Gheorghe Calciu-Dumitreasa By Patricia Sullivan Washington Post Staff Writer Sunday, 26 November 2006; p. C09 https://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2006/11/25/AR2006112500783.html

- ^ Ostling, Richard. "Cross meets Kremlin" TIME Magazine, 24 June 2001. http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,150718,00.html Archived 22 July 2007 at WebCite

- ^ Derek Holmes, History of the Papacy, p. 102.

- ^ Derek Holmes, History of the Papacy, p. 116.

- ^ John Vidmar, The Catholic Church Through the Ages: A History (New York: Paulist Press, 2005), p. 332 & n. 37.

- ^ John Vidmar, The Catholic Church Through the Ages: A History (New York: Paulist Press, 2008), p. 332.

- ^ Derek Holmes, History of the Papacy, p. 158.

- ^ http://www.catholicarrogance.org/Catholic/Hitlersfaith-1.html

Further reading[edit]

- Bowden, John. Encyclopedia of Christianity (2005), 1406 pp excerpt and text search

- Cameron, Averil (1994). Christianity and the Rhetoric of Empire: The Development of Christian Discourse. Berkeley, California: University of California Press. p. 275. ISBN 0-520-08923-5.

- Carrington, Philip. The Early Christian Church (2 vol. 1957) vol 1; online edition vol 2

- Edwards, Mark (2009). Catholicity and Heresy in the Early Church. Ashgate. ISBN 9780754662914.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- González, Justo L. (1984). The Story of Christianity: Vol. 1: The Early Church to the Reformation. Harper. ISBN 0-06-063315-8.; The Story of Christianity, Vol. 2: The Reformation to the Present Day. 1985. ISBN 0-06-063316-6.

- Grabar, André (1968). Christian iconography, a study of its origins. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-01830-8.

- Hastings, Adrian (1999). A World History of Christianity. Grand Rapids: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. ISBN 0-8028-4875-3.

- Holt, Bradley P. Thirsty for God: A Brief History of Christian Spirituality (2nd ed. 2005)

- Jacomb-Hood, Anthony. Rediscovering the New Testament Church. CreateSpace (2014). ISBN 978-1978377585.

- Johnson, Paul. A History of Christianity (1976) excerpt and text search

- Koschorke, Klaus; et al. (2007). A History of Christianity in Asia, Africa, and Latin America, 1450–1990: A Documentary Sourcebook. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. ISBN 9780802828897. excerpt and text search and highly detailed table of contents

- Latourette, Kenneth Scott (1975). A History of Christianity, Volume 1: Beginnings to 1500 (revised ed.). Harper. ISBN 0-06-064952-6. excerpt and text search; A History of Christianity, Volume 2: 1500 to 1975. 1975. ISBN 0-06-064953-4.

- Livingstone, E. A., ed. The Concise Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church (2nd ed. 2006) excerpt and text search online at Oxford Reference

- MacCulloch, Diarmaid. A History of Christianity: The First Three Thousand Years (2010)

- McLeod, Hugh, and Werner Ustorf, eds. The Decline of Christendom in Western Europe, 1750–2000 (2003) 13 essays by scholars; online edition

- McGuckin, John Anthony. The Orthodox Church: An Introduction to its History, Doctrine, and Spiritual Culture (2010), 480pp excerpt and text search

- McGuckin, John Anthony. The Encyclopedia of Eastern Orthodox Christianity (2011), 872pp

- Moore, Edward Caldwell. The Spread of Christianity in the Modern World. Chicago, Ill: University of Chicago Press, 1919.

- Shelley, Bruce L. (1996). Church History in Plain Language (2nd ed.). ISBN 0-8499-3861-9.

- Ricciotti, Giuseppe (1999). Julian the Apostate: Roman Emperor (361-363). TAN Books. ISBN 1505104548.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Stark, Rodney. The Rise of Christianity (1996)

- Tomkins, Stephen. A Short History of Christianity (2006) excerpt and text search

External links[edit]

|

The following links give an overview of the history of Christianity:

|

The following links provide quantitative data related to Christianity and other major religions, including rates of adherence at different points in time:

|