Great Mosque of Mecca

| Great Mosque of Mecca | |

|---|---|

The Great Mosque during the Hajj of 2009 | |

| Religion | |

| Affiliation | Islam |

| Leadership | Abdur Rahman As-Sudais Saud Al-Shuraim Salih Humaid Ali Ahmed Mullah (Chief Mu'azzin) |

| Location | |

| Location | Mecca, Hejaz, Saudi Arabia[1] |

| Administration | Saudi Arabian government |

| Geographic coordinates | 21°25′19″N 39°49′34″E / 21.422°N 39.826°ECoordinates: 21°25′19″N 39°49′34″E / 21.422°N 39.826°E |

| Architecture | |

| Type | Mosque |

| Date established | Era of Abraham in Islamic thought[2] |

| Specifications | |

| Capacity | 1.5 million worshippers[3] |

| Length | 400.800 m |

| Minaret(s) | 9 |

| Minaret height | 89 m (292 ft) |

| Site area | 356,000 square metres[3] |

| Part of a series on |

| Islam |

|---|

|

The Great Mosque of Mecca, commonly known as al-Masjid al-Ḥarām (Arabic: اَلْمَسْجِدُ ٱلْحَرَامُ, romanized: al-Masjid al-Ḥarām, lit. 'The Sacred Mosque'),[4] is a mosque that surrounds the Kaaba in the city of Mecca, in the Hejazi region of Saudi Arabia. It is a site of pilgrimage for the Hajj, which every Muslim must do at least once in their lives if able, and is also the main phase for the ʿUmrah, the lesser pilgrimage that can be undertaken any time of the year. The rites of both pilgrimages include circumambulating the Kaaba within the mosque. The Great Mosque includes other important significant sites, including the Black Stone, the Zamzam Well, Maqam Ibrahim, and the hills of Safa and Marwa.[5]

The Great Mosque is the largest mosque in the world, and the second largest building in the world behind the Boeing Everett Factory. The Great Mosque has undergone major renovations and expansions through the years.[6] It has passed through the control of various caliphs, sultans and kings, and is now under the control of the King of Saudi Arabia who is titled the Custodian of the Two Holy Mosques.[7]

History[edit]

The Great Mosque contends with the Mosque of the Companions in the Eritrean city of Massawa[8] and Quba Mosque in Medina as the oldest mosque.[9] According to one set of views, Islam as a religion preceded Prophet Muhammad,[10][11][12] representing previous prophets such as Abraham.[13] Abraham is credited with having built the Kaaba in Mecca, and consequently its sanctuary, which according to this view is seen as the first mosque[14] that ever existed.[15][16][17] According to another set of views, Islam started during the lifetime of Prophet Muhammad in the 7th century CE,[18] and so did architectural components such as the mosque. In that case, either the Mosque of the Companions[19] or Quba Mosque would be the first mosque that was built in the history of Islam.[14]

Era of Abraham and Ishmael[edit]

According to the Quran, Abraham together with his son Ishmael raised the foundations of a house,[20] which has been identified by commentators[by whom?] as the Kaaba. God showed Abraham the exact site, very near to what is now the Well of Zamzam, where Abraham and Ishmael began work on the construction of the Kaaba. After Abraham had built the Kaaba, an angel brought to him the Black Stone, a celestial stone that, according to tradition, had fallen from Heaven on the nearby hill Abu Qubays. The Black Stone is believed[by whom?] to be the only remnant of the original structure made by Abraham.

After placing the Black Stone in the Eastern corner of the Kaaba, Abraham received a revelation, in which God told the aged prophet that he should now go and proclaim the pilgrimage to mankind, so that men may come both from Arabia and from lands far away, on camel and on foot.[21]

Era of Muhammad[edit]

Upon Muhammad's victorious return to Mecca in 630 CE, he and his cousin, Ali Ibn Abi Talib, broke the idols in and around the Kaaba,[22][better source needed] similar to what, according to the Quran, Abraham did in his homeland.[citation needed] Thus ended polytheistic use of the Kaaba, and began monotheistic rule over it and its sanctuary.[23][24][25][26]

Umayyad era[edit]

The first major renovation to the mosque took place in 692 on the orders of Abd al-Malik ibn Marwan.[27] Before this renovation, which included the mosque's outer walls being raised and decoration added to the ceiling, the mosque was a small open area with the Kaaba at the center. By the end of the 8th century, the mosque's old wooden columns had been replaced with marble columns and the wings of the prayer hall had been extended on both sides along with the addition of a minaret on the orders of Al-Walid I.[28][29] The spread of Islam in the Middle East and the influx of pilgrims required an almost complete rebuilding of the site which included adding more marble and three more minarets.[citation needed]

Ottoman era[edit]

In 1570, Sultan Selim II commissioned the chief architect Mimar Sinan to renovate the mosque. This renovation resulted in the replacement of the flat roof with domes decorated with calligraphy internally, and the placement of new support columns which are acknowledged as the earliest architectural features of the present mosque. These features are the oldest surviving parts of the building.

During heavy rains and flash floods in 1621 and 1629, the walls of the Kaaba and the mosque suffered extensive damage.[30] In 1629, during the reign of Sultan Murad IV, the mosque was renovated. In the renovation of the mosque, a new stone arcade was added, three more minarets (bringing the total to seven) were built, and the marble flooring was retiled. This was the unaltered state of the mosque for nearly three centuries.

Saudi era[edit]

First Saudi expansion[edit]

The first major renovation under the Saudi kings was done between 1955 and 1973. In this renovation, four more minarets were added, the ceiling was refurnished, and the floor was replaced with artificial stone and marble. The Mas'a gallery (As-Safa and Al-Marwah) is included in the Mosque, via roofing and enclosures. During this renovation many of the historical features built by the Ottomans, particularly the support columns, were demolished.

On 20 November 1979, the Great Mosque was seized by extremist insurgents who called for the overthrow of the Saudi dynasty. They took hostages and in the ensuing siege hundreds were killed. These events came as a shock to the Islamic world, as violence is strictly forbidden within the mosque.[citation needed]

Second Saudi expansion[edit]

The second Saudi renovations under King Fahd, added a new wing and an outdoor prayer area to the mosque. The new wing, which is also for prayers, is reached through the King Fahd Gate. This extension was performed between 1982 and 1988.[31]

1988 to 2005 saw the building of more minarets, the erecting of a King's residence overlooking the mosque and more prayer area in and around the mosque itself. These developments took place simultaneously with those in Arafat, Mina and Muzdalifah. This extension also added 18 more gates, three domes corresponding in position to each gate and the installation of nearly 500 marble columns. Other modern developments added heated floors, air conditioning, escalators and a drainage system.[citation needed]

Third Saudi expansion[edit]

In 2008, the Saudi government under King Abdullah Ibn Abdulaziz announced an expansion of the mosque, involving the expropriation of land to the north and northwest of the mosque covering 300,000 square metres (3,200,000 sq ft) . At that time, the mosque covered an area of 356,800 square metres (3,841,000 sq ft) including indoor and outdoor praying spaces. 40 billion riyals (US$10.6 billion) was allocated for the expansion project.[32]

In August 2011, the government under King Abdullah announced further details of the expansion. It would cover an area of 400,000 m2 (4,300,000 sq ft) and accommodate 1.2 million worshippers, including a multi-level extension on the north side of the complex, new stairways and tunnels, a gate named after King Abdullah, and two minarets, bringing the total number of minarets to eleven. The circumambulation areas (Mataf) around the Kaaba would be expanded and all closed spaces receive air conditioning. After completion, it would raise the mosque's capacity from 770,000 to over 2.5 million worshippers.[33][34] his successor King Salman launched five megaprojects as part of the overall King Abdullah Expansion Project in July 2015, covering an area of 456,000 square metres (4,910,000 sq ft). The project was carried out by the Saudi Binladin Group.[35]

On 11 September 2015, at least 111 people died and 394 were injured when a crane collapsed onto the mosque.[36][37][38][39][40] Construction work was suspended after the incident, and remained on hold due to financial issues during the 2010s oil glut. Development was eventually restarted two years later in September 2017.[41]

On 5 March 2020, safety protocols went into place in the Grand Mosque, limiting the activity of the pilgrims, including the suspension of the Umrah pilgrimage and closure of the mosque during the night. This was due to the COVID-19 outbreak.[42]

List of former Imams and Mu'adhins[edit]

Imams:[43]

- Abdullah Al-Khulaifi (Arabic: عَبْد ٱلله ٱلْخُلَيْفِي)

- Ahmad Khatib (Arabic: أَحْمَد خَطِيْب), Islamic Scholar from Indonesia

- Ali bin Abdullah Jaber (Arabic: عَلِى بِن عَبْدُ ٱلله جَابِر), Maliki Jurist of Mecca

- Umar Al-Subayyil (Arabic: عُمَر ٱلسُّبَيِّل), active member of Khatame-Nabbuwwat Organisation

- Muhammad Al-Subayyil (Arabic: مُحَمَّد ٱلسُّبَيِّل), died in 2013

- Abdullah Al-Harazi (Arabic: عَبْد ٱلله الْحَرَازِي), former Chairman of Saudi Majlis al-Shura

- Ali bin Abdur-Rahman Al-Huthaify (Arabic: عَلِي بِن عَبْدُ ٱلرَّحۡمٰن ٱلْحُذَيْفِي), now Chief Imam of The Prophet's Mosque, and member of Saudi Arabia's Al-Hilaal Committee

- Salah ibn Muhammad Al-Budair (Arabic: صَلَاح ابْن مُحَمَّد ٱلْبُدَيْر), now Deputy Chief Imam of the Prophet's Mosque

- Adil al-Kalbani[44] (Arabic: عَادِل ٱلْكَلْبَانِي)

- Salih al Talib (suspended)

- Khalid al Ghamdi (suspended)

Current Imams[edit]

This section does not cite any sources. (March 2020) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

- Abdur-Rahman As-Sudais (Chief Imam)

- Saud Al-Shuraim (Deputy Chief Imam)

- Salih bin Abdullah al Humaid

- Usama Abdul Aziz Al-Khayyat

- Abdullah Awad Al Juhany

Pilgrimage[edit]

The Great Mosque is the main setting for the Hajj and Umrah pilgrimages[46] that occur in the month of Dhu al-Hijjah in the Islamic calendar and at any time of the year, respectively. The Hajj pilgrimage is one of the Pillars of Islam, required of all able-bodied Muslims who can afford the trip. In recent times, over 5 million Muslims perform the Hajj every year.[47]

Structures[edit]

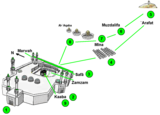

- The Ka'bah is a cuboid-shaped building in the center of the Great Mosque and one of the most sacred sites in Islam.[48] It is the focal point for Islamic rituals like prayer and pilgrimage.[48][49][50]

- The Black Stone is the eastern cornerstone of the Kaaba and plays a role in the pilgrimage.[51][52]

- The Station of Abraham is a rock that reportedly has an imprint of Abraham's foot and is kept in a crystal dome next to the Kaaba.[53]

- Safa and Marwah are two hills between which Abraham's wife Hagar ran, looking for water for her infant son Ishmael, an event which is commemorated in the saʿy ritual of the pilgrimage.[citation needed]

- The Zamzam Well is the water source which, according to tradition, sprang miraculously after Hagar was unable to find water between Safa and Marwah.[citation needed]

Destruction of heritage sites[edit]

There has been some controversy that the expansion projects of the mosque and Mecca itself are causing harm to early Islamic heritage. Many ancient buildings, some more than a thousand years old, have been demolished to make room for the expansion. Some examples are:[54][55]

- Bayt Al-Mawlīd, the house where Muhammad was born, was demolished and rebuilt as a library.[citation needed]

- Dār Al-Arqam, the Islamic school where Muhammad first taught, was flattened to lay marble tiles.[citation needed]

- The house of Abu Jahal has been demolished and replaced by public washrooms.[citation needed]

- A dome that served as a canopy over the Well of Zamzam was demolished.[citation needed]

- Some Ottoman porticos at the Mosque were demolished[citation needed], and those remaining are under threat.

See also[edit]

- Grand Mosque seizure

- Al-Aqsa Mosque, Jerusalem

- Holiest sites in Islam

- Ḥ-R-M

- List of famous mosques

- List of the oldest mosques

- List of mosques in Saudi Arabia

- Lists of mosques

Notes[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ "Location of Masjid al-Haram". Google Maps. Retrieved 24 September 2013.

- ^ Zeitlin, I. M. (25 April 2013). "3". The Historical Muhammad. John Wiley and Sons. ISBN 0745654886.

- ^ a b Daye, Ali (21 March 2018). "Grand Mosque Expansion Highlights Growth of Saudi Arabian Tourism Industry (6 mins)". Cornell Real Estate Review. Retrieved 9 February 2019.

- ^ Denny, Frederick M. (9 August 1990). Kieckhefer, Richard; Bond, George D. (eds.). Sainthood: Its Manifestations in World Religions. University of California Press. p. 69.

- ^ Quran 3:97 (Translated by Yusuf Ali)

- ^ "Mecca crane collapse: Saudi inquiry into Grand Mosque disaster". BBC News.

- ^ "Is Saudi Arabia Ready for Moderate Islam? - Latest Gulf News". www.fairobserver.com. Retrieved 25 November 2017.

- ^ Reid, Richard J. (12 January 2012). "The Islamic Frontier in Eastern Africa". A History of Modern Africa: 1800 to the Present. John Wiley and Sons. p. 106. ISBN 0470658983. Retrieved 15 March 2015.

- ^ Palmer, A. L. (26 May 2016). Historical Dictionary of Architecture (2 ed.). Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 185–236. ISBN 1442263091.

- ^ Esposito, John (1998). Islam: The Straight Path (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. pp. 9, 12. ISBN 978-0-19-511234-4.

- ^ Esposito (2002b), pp. 4–5.

- ^ Peters, F.E. (2003). Islam: A Guide for Jews and Christians. Princeton University Press. p. 9. ISBN 978-0-691-11553-5.

- ^ Alli, Irfan (26 February 2013). 25 Prophets of Islam. eBookIt.com. ISBN 978-1456613075.

- ^ a b Palmer, A. L. (26 May 2016). Historical Dictionary of Architecture (2nd ed.). Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 185–236. ISBN 978-1442263093.

- ^ Michigan Consortium for Medieval and Early Modern Studies (1986). Goss, V. P.; Bornstein, C. V. (eds.). The Meeting of Two Worlds: Cultural Exchange Between East and West During the Period of the Crusades. 21. Medieval Institute Publications, Western Michigan University. p. 208. ISBN 978-0918720580.

- ^ Mustafa Abu Sway. "The Holy Land, Jerusalem and Al-Aqsa Mosque in the Qur'an, Sunnah and other Islamic Literary Source" (PDF). Central Conference of American Rabbis. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 July 2011.

- ^ Dyrness, W. A. (29 May 2013). Senses of Devotion: Interfaith Aesthetics in Buddhist and Muslim Communities. 7. Wipf and Stock Publishers. p. 25. ISBN 978-1620321362.

- ^ Watt, William Montgomery (2003). Islam and the Integration of Society. Psychology Press. p. 5. ISBN 978-0-415-17587-6.

- ^ Reid, Richard J. (12 January 2012). "The Islamic Frontier in Eastern Africa". A History of Modern Africa: 1800 to the Present. John Wiley and Sons. p. 106. ISBN 978-0470658987. Retrieved 15 March 2015.

- ^ Quran 2:127 (Translated by Yusuf Ali)

- ^ Quran 22:27

- ^ Quran 21:57–58

- ^ Mecca: From Before Genesis Until Now, M. Lings, pg. 39, Archetype

- ^ Concise Encyclopedia of Islam, C. Glasse, Kaaba, Suhail Academy

- ^ Ibn Ishaq, Muhammad (1955). Ibn Ishaq's Sirat Rasul Allah – The Life of Muhammad Translated by A. Guillaume. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 88–9. ISBN 9780196360331.

- ^ Karen Armstrong (2002). Islam: A Short History. p. 11. ISBN 0-8129-6618-X.

- ^ Guidetti, Mattia (2016). In the Shadow of the Church: The Building of Mosques in Early Medieval Syria: The Building of Mosques in Early Medieval Syria. BRILL. p. 113. ISBN 9789004328839. Retrieved 17 September 2017.

- ^ Petersen, Andrew (2002). Dictionary of Islamic Architecture. Routledge. ISBN 9781134613656. Retrieved 17 September 2017.

- ^ Ali, Wijdan (1999). The Arab Contribution to Islamic Art: From the Seventh to the Fifteenth Centuries. American Univ in Cairo Press. ISBN 9789774244766. Retrieved 17 September 2017.

- ^ James Wynbrandt (2010). A Brief History of Saudi Arabia. Infobase Publishing. p. 101. ISBN 978-0-8160-7876-9. Retrieved 12 June 2013.

- ^ "Gates of Masjid al-Haram". Madain Project. Retrieved 17 March 2018.

- ^ "Riyadh Expands Masjid al-Haram". OnIslam.net. 6 January 2008. Archived from the original on 28 December 2013.

- ^ "Historic Masjid Al-Haram Extension Launched". onislam. 20 August 2011. Archived from the original on 12 May 2012. Retrieved 17 November 2011.

- ^ "Saudi Arabia starts Mecca mosque expansion". reuters.com.

- ^ "King launches key Grand Mosque expansion projects". Saudi Gazette. 12 July 2015. Retrieved 9 February 2019.

- ^ "Makkah crane crash report submitted". Al Arabiya. 14 September 2015. Retrieved 15 September 2015.

- ^ "King Salman to make findings of Makkah crane collapse probe public". Retrieved 14 September 2015.

- ^ "Number of casualties of Turkish Haji candidates at the Kaaba accident reach 8…". Presidency of Religious Affairs. 13 September 2015. Archived from the original on 26 September 2015. Retrieved 15 September 2015.

- ^ "Six Nigerians among victims of Saudi crane accident: official". Yahoo! News. AFP. 16 September 2015. Retrieved 16 September 2015.

- ^ Halkon, Ruth; Webb, Sam (13 September 2015). "Two Brits dead and three injured in Mecca Grand Mosque crane tragedy that killed 107 people l". Mirror Online. Retrieved 16 September 2015.

- ^ "Saudi Arabia to restart work on $26.6 bln Grand Mosque expansion". Reuters. 17 August 2017. Retrieved 14 February 2019.

- ^ "Saudi Arabia announces extraordinary measures to protect Mecca and Medina from coronavirus". Middle East Eye. Retrieved 8 March 2020.

- ^ "Names of Former Imams 1345–1435 Ah". Retrieved 3 May 2018.

- ^ WORTH, ROBERT F. (10 April 2009). "A Black Imam Breaks Ground in Mecca". The New York Times. Riyadh.

- ^ "Imām ibn Kathīr al-Makkī". Propheticguidance.co.uk. 16 June 2013. Retrieved 13 April 2016.

- ^ Mohammed, Mamdouh N. (1996). Hajj to Umrah: From A to Z. Mamdouh Mohammed. ISBN 0-915957-54-X.

- ^ General statistics of the Umrah season of 1436 A.H. until 24:00 hours, 28/09/1436 A.H. Total Number of the Mu`tamirs: 5,715,051 "General statistics of the Umrah season of 1436 A.H." The Ministry of Hajj, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Archived from the original on 13 August 2015.

- ^ a b Wensinck, A. J; Ka`ba. Encyclopaedia of Islam IV p. 317

- ^ "In pictures: Hajj pilgrimage". BBC News. 7 December 2008. Retrieved 8 December 2008.

- ^ "As Hajj begins, more changes and challenges in store". altmuslim. Archived from the original on 11 January 2012.

- ^ Shaykh Safi-Ar-Rahman Al-Mubarkpuri (2002). Ar-Raheeq Al-Makhtum (The Sealed Nectar): Biography of the Prophet. Dar-As-Salam Publications. ISBN 1-59144-071-8.

- ^ Mohamed, Mamdouh N. (1996). Hajj to Umrah: From A to Z. Amana Publications. ISBN 0-915957-54-X.

- ^ M.J. Kister, "Maḳām Ibrāhīm," p.105, The Encyclopaedia of Islam (new ed.), vol. VI (Mahk-Mid), eds. Bosworth et al., Brill: 1991, pp. 104-107.

- ^ Taylor, Jerome (24 September 2011). "Mecca for the Rich: Islam's holiest site turning into Vegas". The Independent.

- ^ Abou-Ragheb, Laith (12 July 2005). "Dr.Sami Angawi on Wahhabi Desecration of Makkah". Center for Islamic Pluralism. Retrieved 28 November 2010.

External links[edit]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Great Mosque of Mecca. |