Apep

| Apep/Apophis | |

|---|---|

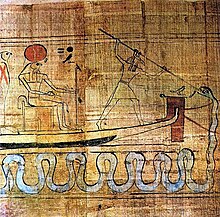

Atum and the snake Apophis | |

| Symbol | Snake |

| Personal information | |

| Parents | Neith (in some myths) |

| Siblings | Ra |

| Part of a series on |

| Ancient Egyptian religion |

|---|

|

|

Beliefs |

|

Practices |

|

Locations |

|

|

Related religions |

|

|

Apep (/ˈæpɛp/ or /ˈɑːpɛp/; also spelled Apepi or Aapep) or Apophis (/ˈæpəfɪs/; Ancient Greek: Ἄποφις) was the ancient Egyptian deity who embodied chaos (ı͗zft in Egyptian) and was thus the opponent of light and Ma'at (order/truth). He appears in art as a giant serpent. His name is reconstructed by Egyptologists as *ʻAʼpāp(ī), as it was written ꜥꜣpp(y) and survived in later Coptic as Ⲁⲫⲱⲫ Aphōph.[1] Apep was first mentioned in the Eighth Dynasty, and he was honored in the names of the Fourteenth Dynasty king 'Apepi and of the Greater Hyksos king Apophis.

Development[edit]

| ||||

| Apep in hieroglyphs |

|---|

Ra was the solar deity, bringer of light, and thus the upholder of Ma'at. Apep was viewed as the greatest enemy of Ra, and thus was given the title Enemy of Ra, and also "the Lord of Chaos".

Apep was seen as a giant snake or serpent leading to such titles as Serpent from the Nile and Evil Dragon. Some elaborations said that he stretched 16 yards in length and had a head made of flint. Already on a Naqada I (c. 4000 BC) C-ware bowl (now in Cairo) a snake was painted on the inside rim combined with other desert and aquatic animals as a possible enemy of a deity, possibly a solar deity, who is invisibly hunting in a big rowing vessel.[3]

While in most texts Apep is described as a giant snake, he is sometimes depicted as a crocodile.[4]

The few descriptions of Apep's origin in myth usually demonstrate that it was born after Ra, usually from his umbilical cord. Combined with its absence from Egyptian creation myths, this has been interpreted as suggesting that Apep was not a primordial force in Egyptian theology, but a consequence of Ra's birth. This suggests that evil in Egyptian theology is the consequence of an individual's own struggles against non-existence.[5]

Battles with Ra[edit]

Tales of Apep's battles against Ra were elaborated during the New Kingdom.[7] Storytellers said that every day Apep must lay below the horizon and not persist in the mortal kingdom. This appropriately made him a part of the underworld. In some stories, Apep waited for Ra in a western mountain called Bakhu, where the sun set, and in others, Apep lurked just before dawn, in the Tenth region of the Night. The wide range of Apep's possible locations gained him the title World Encircler. It was thought that his terrifying roar would cause the underworld to rumble. Myths sometimes say that Apep was trapped there, because he had been the previous chief god overthrown by Ra, or because he was evil and had been imprisoned.

The Coffin Texts imply that Apep used a magical gaze to overwhelm Ra and his entourage.[8] Ra was assisted by a number of defenders who travelled with him, including Set and possibly the Eye of Ra.[9] Apep's movements were thought to cause earthquakes, and his battles with Set may have been meant to explain the origin of thunderstorms. In one account, Ra himself defeats Apep in the form of a cat.[10]

What few accounts there are of Apep's origin usually describe it as being born from Ra's umbilical cord.[5]

Worship[edit]

Ra's victory each night was thought to be ensured by the prayers of the Egyptian priests and worshippers at temples. The Egyptians practiced a number of rituals and superstitions that were thought to ward off Apep, and aid Ra in continuing his journey across the sky.

In an annual rite called the Banishing of Chaos, priests would build an effigy of Apep that was thought to contain all of the evil and darkness in Egypt, and burn it to protect everyone from Apep's evil for another year.

The Egyptian priests had a detailed guide to fighting Apep, referred to as The Books of Overthrowing Apep (or the Book of Apophis, in Greek).[11] The chapters described a gradual process of dismemberment and disposal, and include:

- Spitting Upon Apep

- Defiling Apep with the Left Foot

- Taking a Lance to Smite Apep

- Fettering Apep

- Taking a Knife to Smite Apep

- Putting Fire Upon Apep

In addition to stories about Ra's victories, this guide had instructions for making wax models, or small drawings, of the serpent, which would be spat on, mutilated and burnt, whilst reciting spells that would kill Apep. Fearing that even the image of Apep could give power to the demon, any rendering would always include another deity to subdue the monster.

As Apep was thought to live in the underworld, he was sometimes thought of as an Eater of Souls. Thus the dead also needed protection, so they were sometimes buried with spells that could destroy Apep. The Book of the Dead does not frequently describe occasions when Ra defeated the chaos snake explicitly called Apep. Only Book of the Dead Spells 7 and 39 can be explained as such.[12]

In popular culture[edit]

See also[edit]

- Apep (star system), triple star system that is a gamma-ray burst progenitor in the Milky Way

- 99942 Apophis, near Earth asteroid

- Egyptian influence in popular culture

- Ethnoherpetology

- Jörmungandr

- Mehen

- Ouroboros

- Unut

- Wadjet

- Vritra

Notes[edit]

- ^ a b Erman, Adolf, and Hermann Grapow, eds. 1926–1953. Wörterbuch der aegyptischen Sprache im Auftrage der deutschen Akademien. 6 vols. Leipzig: J. C. Hinrichs'schen Buchhandlungen. (Reprinted Berlin: Akademie-Verlag GmbH, 1971).

- ^ Hieroglyph as per Budge Gods of the Ancient Egyptians (1969), Vol. I, 180.

- ^ C. Wolterman, in Jaarbericht van Ex Oriente Lux, Leiden Nr.37 (2002).

- ^ S., Mercatante, Anthony (2009). The Facts on File encyclopedia of world mythology and legend. Dow, James R. (3rd ed.). New York: Facts On File. ISBN 9780816073115. OCLC 184982566.

- ^ a b Kemboly, Mpay. 2010. The Question of Evil in Ancient Egypt. London: Golden House Publications.

- ^ tomb of Inherkha, Deir el-Medina

- ^ J. Assmann, Egyptian Solar Religion in the New Kingdom, transl. by A. Alcock (London, 1995), 49-57.

- ^ Borghouts, J. F. (1973). "The Evil Eye of Apopis". The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 59. 114–115.

- ^ Borghouts, J. F. (1973). "The Evil Eye of Apopis". The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 59. 116.

- ^ G. Pinch, Egyptian Mythology, (2004), pp. 107–108

- ^ P.Kousoulis, Magic and Religion as Performative Theological Unity: the Apotropaic Ritual of Overthrowing Apophis, Ph.D. dissertation, University of Liverpool (Liverpool, 1999), chapters 3-5.

- ^ J.F.Borghouts, Book of the Dead [39]: From Shouting to Structure (Studien zum Altaegyptischen Totenbuch 10, Wiesbaden, 2007).

External links[edit]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Apep. |