Mut

| Mut | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

A contemporary image of goddess Mut, depicted as a woman wearing the double crown plus a royal vulture headdress, associating her with Nekhbet. | |||||

| Name in hieroglyphs |

| ||||

| Major cult center | Thebes | ||||

| Symbol | the Vulture | ||||

| Personal information | |||||

| Parents | Ra | ||||

| Siblings | Sekhmet, Hathor, Ma'at and Bastet | ||||

| Consort | Amun | ||||

| Offspring | Khonsu | ||||

Mut, also known as Maut and Mout, was a mother goddess worshipped in ancient Egypt. Her name literally means mother in the ancient Egyptian language.[1] Mut had many different aspects and attributes that changed and evolved a lot over the thousands of years of ancient Egyptian culture.

Mut was considered a primal deity, associated with the primordial waters of Nu from which everything in the world was born. Mut was sometimes said to have given birth to the world through parthenogenesis, but more often she was said to have a husband, the solar creator god Amun-Ra. Although Mut was believed by her followers to be the mother of everything in the world, she was particularly associated as the mother of the lunar child god Khonsu. At the Temple of Karnak in Egypt's capital city of Thebes, the family of Amun-Ra, Mut and Khonsu were worshipped together as the Theban Triad.

In art, Mut was usually depicted as a woman wearing the double crown of the kings of Egypt, representing her power over the whole of the land.

During the high point of Mut's cult, the rulers of Egypt would support her worship in their own way to emphasize their own authority and right to rule through an association with Mut. Mut was involved in many ancient Egyptian festivals such as the Opet Festival and the Beautiful Festival of the Valley. Her greatest temple was located at Karnak in Thebes.

Mythology[edit]

| Part of a series on |

| Ancient Egyptian religion |

|---|

|

|

Beliefs |

|

Practices |

|

Locations |

|

|

Related religions |

|

|

Mut was the consort of Amun, the patron deity of pharaohs during the Middle Kingdom (c. 2055–1650 BC) and New Kingdom (c. 1550–1070 BC). Amaunet and Wosret may have been Amun's consorts early in Egyptian history, but Mut, who did not appear in texts or art until the late Middle Kingdom, displaced them. In the New Kingdom, Amun and Mut were the patron deities of Thebes, a major city in Upper Egypt, and formed a cultic triad with their son, Khonsu. Her other major role was as a lioness deity, an Upper Egyptian counterpart to the fearsome Lower Egyptian goddess Sekhmet.[2]

Depictions[edit]

In art, Mut was pictured as a woman with the wings of a vulture, holding an ankh, wearing the united crown of Upper and Lower Egypt and a dress of bright red or blue, with the feather of the goddess Ma'at at her feet.

Alternatively, as a result of her assimilations, Mut is sometimes depicted as a cobra, a cat, a cow, or as a lioness as well as the vulture.

Before the end of the New Kingdom almost all images of female figures wearing the Double Crown of Upper and Lower Egypt were depictions of the goddess Mut, here labeled "Lady of Heaven, Mistress of All the Gods". The last image on this page shows the goddess's facial features which mark this as a work made sometime between late Dynasty XVIII and relatively early in the reign of Ramesses II (c. 1279–1213 BC).[3]

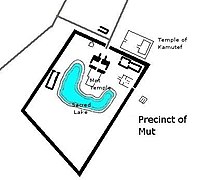

In Karnak[edit]

There are temples dedicated to Mut still standing in modern-day Egypt and Sudan, reflecting the widespread worship of her. The center of her cult in Sudan became the Mut Temple of Jebel Barkal and in Egypt the temple in Karnak. That temple had the statue that was regarded as an embodiment of her real ka. Her devotions included daily rituals by the pharaoh and her priestesses. Interior reliefs depict scenes of the priestesses, currently the only known remaining example of worship in ancient Egypt that was exclusively administered by women.

Usually the queen served as the chief priestess in the temple rituals. The pharaoh participated also and would become a deity after death. In the case when the pharaoh was female, records of one example indicate that she had her daughter serve as the high priestess in her place. Often priests served in the administration of temples and oracles where priestesses performed the traditional religious rites. These rituals included music and drinking.

The pharaoh Hatshepsut had the ancient temple to Mut at Karnak rebuilt during her rule in the Eighteenth Dynasty. Previous excavators had thought that Amenhotep III had the temple built because of the hundreds of statues found there of Sekhmet that bore his name. However, Hatshepsut, who completed an enormous number of temples and public buildings, had completed the work seventy-five years earlier. She began the custom of depicting Mut with the crown of both Upper and Lower Egypt. It is thought that Amenhotep III removed most signs of Hatshepsut, while taking credit for the projects she had built.

Hatshepsut was a pharaoh who brought Mut to the fore again in the Egyptian pantheon, identifying strongly with the goddess. She stated that she was a descendant of Mut. She also associated herself with the image of Sekhmet, as the more aggressive aspect of the goddess, having served as a very successful warrior during the early portion of her reign as pharaoh.

Later in the same dynasty, Akhenaten suppressed the worship of Mut as well as the other deities when he promoted the monotheistic worship of his sun god, Aten. Tutankhamun later re-established her worship and his successors continued to associate themselves with Mut afterward.

Ramesses II added more work on the Mut temple during the nineteenth dynasty, as well as rebuilding an earlier temple in the same area, rededicating it to Amun and himself. He placed it so that people would have to pass his temple on their way to that of Mut.

Kushite pharaohs expanded the Mut temple and modified the Ramesses temple for use as the shrine of the celebrated birth of Amun and Khonsu, trying to integrate themselves into divine succession. They also installed their own priestesses among the ranks of the priestesses who officiated at the temple of Mut.

The Greek Ptolemaic dynasty added its own decorations and priestesses at the temple as well and used the authority of Mut to emphasize their own interests.

Later, the Roman emperor Tiberius rebuilt the site after a severe flood and his successors supported the temple until it fell into disuse, sometime around the third century AD. Later Roman officials used the stones from the temple for their own building projects, often without altering the images carved upon them.

Personal piety[edit]

In the wake of Akhenaten's revolution, and the subsequent restoration of traditional beliefs and practices, the emphasis in personal piety moved towards greater reliance on divine, rather than human, protection for the individual. During the reign of Rameses II a follower of the goddess Mut donated all his property to her temple and recorded in his tomb:

And he [Kiki] found Mut at the head of the gods, Fate and fortune in her hand, Lifetime and breath of life are hers to command ... I have not chosen a protector among men. I have not sought myself a protector among the great ... My heart is filled with my mistress. I have no fear of anyone. I spend the night in quiet sleep, because I have a protector.[4]

References[edit]

- ^ te Velde, Herman (2002), "Mut", in Redford, D. B. (ed.), The Ancient Gods Speak: A Guide to Egyptian Religion, New York: Oxford University Press, p. 238

- ^ Wilkinson, Richard H. (2003). The Complete Gods and Goddesses of Ancient Egypt. Thames & Hudson. pp. 153–155, 169

- ^ "Relief of the Goddess Mut". Brooklyn Museum. Archived from the original on 7 March 2016. Retrieved 17 June 2014.

- ^ Assmann, Jan (2008). Of God and Gods: Egypt, Israel, and the Rise of Monotheism. University of Wisconsin Press. pp. 83–84. ISBN 0-299-22554-2.

- Pinkowski, Jennifer (2006). "Egypt's Ageless Goddess". Archaeology. 59 (5). Retrieved 29 November 2015.

External links[edit]

Media related to Mut at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Mut at Wikimedia Commons