Menorah (Temple)

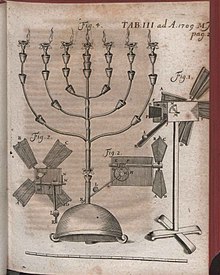

The menorah (/məˈnɔːrə/; Hebrew: מְנוֹרָה [menoˈʁa]) is described in the Bible as the seven-lamp (six branches) ancient Hebrew lampstand made of pure gold and used in the portable sanctuary set up by Moses in the wilderness and later in the Temple in Jerusalem. Fresh olive oil of the purest quality was burned daily to light its lamps. The menorah has been a symbol of Judaism since ancient times and is the emblem on the coat of arms of the modern state of Israel.

Construction[edit]

The Hebrew Bible states that God revealed the design for the menorah to Moses and describes the construction of the menorah as follows (Exodus 25:31–40):

31Make a lampstand of pure gold. Hammer out its base and shaft, and make its flowerlike cups, buds and blossoms of one piece with them. 32Six branches are to extend from the sides of the lampstand—three on one side and three on the other. 33Three cups shaped like almond flowers with buds and blossoms are to be on one branch, three on the next branch, and the same for all six branches extending from the lampstand. 34And on the lampstand are to be four cups shaped like almond flowers with buds and blossoms. 35One bud shall be under the first pair of branches extending from the lampstand, a second bud under the second pair, and a third bud under the third pair—six branches in all. 36The buds and branches shall be all of one piece with the lampstand, hammered out of pure gold.

37Then make its seven lamps and set them up on it so that they light the space in front of it. 38Its wick trimmers and trays are to be of pure gold. 39A talent of pure gold is to be used for the lampstand and all these accessories. 40See that you make them according to the pattern shown you on the mountain.[1]

Numbers, chapter 8, adds that the seven lamps are to give light in front of the lampstand and reiterates that the lampstand was made in accordance with the pattern shown to Moses on the mountain.[2]

In Jewish oral tradition, the menorah stood 18 handbreadths (three common cubits) high, or approximately 1.62 metres (5.3 ft).[3] Although the menorah was placed in the antechamber of the Temple sanctuary, over against its southernmost wall, the Talmud (Menahot 98b) brings down a dispute between two scholars on whether or not the menorah was situated north to south, or east to west. The historian Josephus, who witnessed the Temple's destruction, says that the menorah was actually situated obliquely, to the east and south.[4]

The branches are often artistically depicted as semicircular, but Rashi,[5] (according to some contemporary readings) and Maimonides (according to his son Avraham),[6] held that they were straight;[7] all other Jewish authorities, both classical (e.g. Philo and Josephus) and medieval (e.g. Ibn Ezra) who express an opinion on the subject state that the arms were round.[8] Archaeological evidence, including depictions by artists who had seen the menorah, indicates that they were not straight, but show them as rounded, either semicircular or elliptical.[9][10]

The most famous preserved representation[11] of the menorah of the Temple was depicted in a frieze on the Arch of Titus, commemorating his triumphal parade in Rome following the destruction of Jerusalem in the year 70 CE. In that frieze, the menorah is shown resting upon a hexagonal base, which in turn rests upon a slightly larger but concentric and identically shaped base; a stepwise appearance on all sides is thus produced. Each facet of the hexagonal base was made with two vertical stiles and two horizontal rails, a top rail and a bottom rail, resembling a protruding frame set against a sunken panel. These panels have some relief design set or sculpted within them. The panels depict the Ziz and the Leviathan from Jewish mythology.

In 2009, the ruins of a synagogue with pottery dating from before the destruction of the Second Temple were discovered under land in Magdala owned by the Legionaries of Christ, who had intended to construct a center for women's studies.[12] Inside that synagogue's ruins was discovered a rectangular stone, which had on its surface, among other ornate carvings, a depiction of the seven-lamp menorah differing markedly from the depiction on the Arch of Titus, which could possibly have been carved by an eyewitness to the actual menorah present at the time in the Temple at Jerusalem. This menorah has arms which are polygonal, not rounded, and the base is not graduated but triangular. It is notable, however, that this artifact was found a significant distance from Jerusalem and the Arch of Titus has often been interpreted as an eyewitness account of the original menorah being looted from the temple in Jerusalem.

Representations of the seven lamp artifact have been found on tombs and monuments dating from the 1st century as a frequently used symbol of Judaism and the Jewish people.[13]

It has been noted that the shape of the menorah bears a certain resemblance to that of the plant Salvia palaestina.[14]

Contrary to some modern designs, the ancient menorah burned oil and did not contain anything resembling candles, which were unknown in the Middle East until about 400 CE.

Use[edit]

The lamps of the menorah were lit daily from fresh, consecrated olive oil and burned from evening until morning, according to Exodus 27:21.

The Roman-Jewish historian Flavius Josephus states that three of the seven lamps were allowed to burn during the day also;[15] however, according to one opinion in the Talmud, only the center lamp was left burning all day, into which as much oil was put as into the others.[16] Although all the other lights were extinguished, that light continued burning oil, in spite of the fact that it had been kindled first. This miracle, according to the Talmud, was taken as a sign that the Shechinah rested among Israel.[17] It was called the ner hama'aravi (Western lamp) because of the direction of its wick. This lamp was also referred to as the ner Elohim (lamp of God), mentioned in I Samuel 3:3.[13] According to the Talmud, the miracle of the ner hama'aravi ended after the High Priesthood of Simon the Just in the 3rd or 4th century BCE.[18]

History and fate[edit]

Tabernacle[edit]

The original menorah was made for the Tabernacle, and the Bible records it as being present until the Israelites crossed the Jordan river. When the Tabernacle tent was pitched in Shiloh (Joshua 18:1), it is assumed that the menorah was also present. However, no mention is made of it during the years that the Ark of the Covenant was moved in the times of Samuel and Saul.[citation needed]

Solomon's temple[edit]

There is no further mention of the menorah in Solomon's temple, except in 1 Kings 7:49, 1 Chronicles 28:15 and 2 Chronicles 4:7, which notes that he created ten lampstands. The weight of the lampstands forms part of the detailed instructions given to Solomon by David.

They are recorded as being taken away to Babylon by the invading armies under the general Nebuzar-Adan some centuries later (Jeremiah 52:19).

Second Temple (post-Exile)[edit]

During the restoration of the Temple worship after the captivity in Babylon, no mention is made of the return of the menorah but only of "vessels" (Ezra 1:9-10). Since the new Temple, known as the Second Temple, was an enclosed place with no natural light, some means of illumination must have existed.[citation needed]

The Book of Maccabees records that Antiochus Epiphanes took away the lampstands (plural) when he invaded and robbed the Temple (1 Maccabees 1:21). The later record of the making of "new holy vessels" may refer to the manufacture of new lampstands (1 Maccabees 4:49). There is no biblical mention of the fate of the menorah.[citation needed]

Herod's temple[edit]

Herod the Great had the Second Temple remodeled while not disrupting the temple service.

Rome (70-455 CE)[edit]

The menorah from the Second Temple was carried to Rome after the Roman conquest of Jerusalem in 70 AD during the First Jewish–Roman War. The fate of the menorah used in the Second Temple is recorded by Josephus, who states that it was brought to Rome and carried along during the triumph of Vespasian and Titus. The bas relief on the Arch of Titus in Rome depicts a scene of Roman soldiers carrying away the spoils of the Second Temple, in particular, the seven-branched menorah, or candelabrum. For centuries, the Menorah was displayed as a war trophy at the Temple of Peace in Rome, a Roman temple paid for with spoils taken from the conquered city of Jerusalem. It was still there when the city was conquered by Vandals in 455.[19]

After the 455 Sack of Rome[edit]

Its fate during and after the 455 Sack of Rome is unknown. While it may have been melted down or broken into chunks of gold by the conquerors, it has been variously claimed that it was destroyed in a fire; that it was taken to Carthage, and then to the capital of the Eastern Roman Empire at Constantinople, or that it sank in a shipwreck. Another persistent rumor is that the Vatican has kept it hidden for centuries. Some claim that it has been kept in Vatican City, others that it is in the cellars of the Archbasilica of St. John Lateran.[19]

Most likely, the menorah was looted by the Vandals in the sacking of Rome in 455 CE, and taken to their capital, Carthage.[20] The Byzantine army under General Belisarius might have removed it in 533 and brought it to Constantinople. According to Procopius, it was carried through the streets of Constantinople during Belisarius' triumphal procession.[21] Procopius adds that the object was later sent back to Jerusalem where there is no record of it.[22] It could have been destroyed when Jerusalem was pillaged by the Persians in 614.[citation needed]

In the Avot of Rabbi Natan, one of the minor tractates printed with the Babylonian Talmud, there is a listing of Jewish treasures, which according to Jewish oral tradition are still in Rome, as they have been for centuries.

The objects that were crafted, and then hidden away are these: the tent of meeting and the vessels contained therein, the ark and the broken tablets, the container of manna, and the flask of annointing oil, the stick of Aaron and its almonds and flowers, the priestly garments, and the garments of the annointed [high] priest.

But, the spice-grinder of the family of Avtinas [used to make the unique incense in the Temple], the [golden] table [of the showbread], the menorah, the curtain [that partitioned the holy from the holy-of-holies], and the head-plate are still sitting in Rome.[23]

Symbolism[edit]

Judaism[edit]

The menorah symbolized the ideal of universal enlightenment.[24] The idea that the Menorah symbolizes wisdom is noted in the Talmud, for example, in the following: "Rabbi Isaac said: He who desires to become wise should incline to the south [when praying]. The symbol [by which to remember this] is that… the Menorah was on the southern side [of the Temple]."[25]

The seven lamps allude to the branches of human knowledge, represented by the six lamps inclined inwards towards, and symbolically guided by, the light of God represented by the central lamp. The menorah also symbolizes the creation in seven days, with the center light representing the Sabbath.[13]

Christianity[edit]

SIC•LUCEAT•LUX•VESTRA

(Let your light so shine – Matt. 5:16)

The New Testament Book of Revelation refers to seven golden lampstands, representing the seven churches of Asia to which the revelation was sent (Ephesus, Smyrna, Pergamon, Thyatira, Sardis, Philadelphia and Laodicea), with "one like a Son of Man" in their midst.[26]

According to Clement of Alexandria and Philo Judaeus, the seven lamps of the golden menorah represented the seven classical planets in this order: the Moon, Mercury, Venus, the Sun, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn.[27]

It is also said to symbolize the burning bush as seen by Moses on Mount Horeb (Exodus 3).[28]

Kevin Conner has noted of the original menorah, described in Exodus 25, that each of the six tributary branches coming out of the main shaft was decorated with three sets of "cups... shaped like almond blossoms... a bulb and a flower..." (Exodus 25:33, NASB).[29] This would create three sets of three units on each branch, a total of nine units per branch. The main shaft, however, had four sets of blossoms, bulbs and flowers, making a total of twelve units on the shaft (Exodus 25:34). This would create a total of 66 units, which Conner claims is a picture of the Protestant canon of scripture (containing 66 books). Moreover, Conner notes that the total decorative units on the shaft and three branches equate to 39 (the number of Old Testament books within Protestant versions of the Bible); and the units on the remaining three branches come to 27 (the number of New Testament books).[30] Conner connects this to Bible passages that speak of God's word as a light or lamp (e.g. Psalms 119:105; Psalms 119:130; cf. Proverbs 6:23).[31]

Hanukkah menorah[edit]

The Menorah is also a symbol closely associated with the Jewish holiday of Hanukkah (also spelled Chanukah). According to the Talmud, after the Seleucid desecration of the Jewish Temple in Jerusalem, there was only enough sealed (and therefore not desecrated) consecrated olive oil left to fuel the eternal flame in the Temple for one day. Miraculously, the oil burned for eight days, which was enough time to make new pure oil.

The Talmud (Menahot 28b) states that it is prohibited to use a seven-lamp menorah outside of the Temple. The Hanukkah menorah therefore has eight main branches, plus the raised ninth lamp set apart as the shamash (servant) light which is used to kindle the other lights. This type of menorah is called a hanukiah in Modern Hebrew.[13]

Modern Jewish use[edit]

Synagogues have a continually lit lamp or light in front of the Ark, where the Torah scroll is kept, called the ner tamid (eternal light). This lamp represents the continually lit ner Elohim of the menorah used in Temple times.[13]

In addition, many synagogues display either a Menorah or an artistic representation of a menorah.

A menorah appears in the coat of arms of the State of Israel, based on the depiction of the menorah on the Arch of Titus.

Sometimes when teaching learners of the Hebrew language, a chart shaped like the seven-lamp menorah is used to help students remember the role of the binyanim of the Hebrew verb.

Temple Institute reconstruction[edit]

The Temple Institute has created a life-sized menorah, designed by goldsmith Chaim Odem, intended for use in a future Third Temple. The Jerusalem Post describes the menorah as made "according to excruciatingly exacting Biblical specifications and prepared to be pressed into service immediately should the need arise."[32] The menorah is made of one talent (interpreted as 45 kg) of 24 karat pure gold, hammered out of a single block of solid gold, with decorations based on the depiction of the original in the Arch of Titus and the Temple Institute's interpretation of the relevant religious texts.

In other cultures[edit]

In the Orthodox Church the use of the menorah has been preserved, always standing on or behind the altar in the sanctuary.[33] Though candles may be used, the traditional practice is to use olive oil in the seven-lamp lampstand. There are varying liturgical practices, and usually all seven lamps are lit for the services, though sometimes only the three centermost are lit for the lesser services. If the church does not have a sanctuary lamp the centermost lamp of the seven lamps may remain lit as an eternal flame.

The Menorah has also become a symbol for the Iglesia ni Cristo since the 20th century.

The kinara is also, like the menorah, a seven candleholder which is associated with the African American festival of Kwanzaa. One candle is lit on each day of the week-long celebration, in a similar manner as the Hanukiah (which was modeled after the menorah) during Hanukkah.

In Taoism, the Seven-Star Lamp qi xing deng 七星燈 is a seven-lamp oil lamp lit to represent the seven stars of the Northern Dipper.[34] This lampstand is a requirement for all Taoist temples, never to be extinguished. In the first 9 days of the lunar 9th month festival, an oil lamp of nine connected lamps may also be lit to honour both the Northern Dipper and two other assistant stars (collectively known as the Nine Emperor Stars), sons of Dou Mu appointed by the Taoist Trinity (the Three Pure Ones) to hold the Books of Life and Death of humanity. The lamps represent the illumination of the 7 stars, and lighting them are believed to absolve sins while prolonging one's lifespan.

In popular culture[edit]

The menorah features prominently in the 2013 crypto-thriller The Sword of Moses by Dominic Selwood. It is also featured in the archaeology novels Crusader Gold, by David Gibbins, and The Last Secret of the Temple, by Paul Sussman. A menorah can be seen in the movie X-Men: First Class, when Charles Xavier reads Erik Lehnsherr's mind, searching for a happy memory from his childhood before the Holocaust, and together they see Erik as a young child lighting his first menorah with his mother.

Gallery[edit]

Second Temple period stone tablet from a synagogue in Peki'in, Israel

The Jewish Legion cap badge: menorah and word קדימה Kadima (forward)

A drawing on the depiction of the Menorah seen on the Arch of Titus in Rome, Italy.

The Coat of Arms of Israel shows a menorah surrounded by an olive branch on each side and the writing "ישראל" (Israel) based on its depiction on the Arch of Titus.

The Menorah is seen being sacked as the Holy Temple in Jerusalem was being destroyed by the Roman army. (70 CE)

Menorah monument at Jewish Cemetery of Theresienstadt concentration camp

Menorah monument to the 33,771 Jews murdered at Babi Yar, Ukraine

The Knesset Menorah outside the Knesset (Israeli Parliament).

In this 1806 French print, the woman with the Menorah represents the Jews being emancipated by Napoleon Bonaparte

Kippa and Menorah from the Harry S Truman collection

The Menorah, presented to Tsar Boris III from the Bulgarian Jewish community (Tsarska Bistritsa)

The logo of Paris's Musée d'Art et d'Histoire du Judaïsme

A menorah on the flag of Iglesia ni Cristo

Depiction of the Menorah on a modern replica of the Arch of Titus in Rome

See also[edit]

- Menorah (Hanukkah)

- Jewish symbols

- Arch of Titus

- Hanukkah

- Knesset Menorah

- Mishneh Torah Avodah Laws of the Temple 3:1–10

- Emblem of Israel

References[edit]

- ^ Exodus 25:31-40, New International Version.

- ^ Numbers 8:1-4

- ^ Babylonian Talmud (Menahot 28b); Maimonides, Mishne Torah (Hil. Beit ha-Baḥirah 3:10 ). Figure is based on the accepted rabbinic view that there are four finger-widths to every handbreadth/palm, and each finger-width is estimated at 2.25 cm. This measurement does not include the step-like platform upon which it rested.

- ^ Josephus, Antiquities (Book iii, chapter vi, section 7).

- ^ Rashi, Exodus 25:32

- ^ Commentary on Exodus, ch 7

- ^ Maimonides depicted them as straight in a manuscript drawing, but see Seth Mandel's alternative interpretation below.

- ^ See the Rebbe Menachem Mendel Schneerson, Likkutei Sichot, vol 21, pp 168-171.

- ^ Mandel, Seth The shape of the Menorah of the Temple Avodah Mailing List, Vol 12 Num 65

- ^ See, for example, photographs of ancient depictions at the Jewish Gift Place website.

- ^ The Arch of Titus (Arcus Titi) was erected by Domitian sometime after the death of his brother in 81 CE, making the relief of the menorah one of the oldest representations in existence.

- ^ First-century Synagogue Discovered on Site of Legion’s Magdala Center in Galilee 11 September 2009 - regnumchristi.org

- ^ a b c d e Birnbaum, Philip (1975). A Book of Jewish Concepts. New York: Hebrew Publishing Company. pp. 366–367. ISBN 088482876X.

- ^ JTS Taste of Torah commentary, 18 June 2005 Archived 27 May 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ Shabbat 22b

- ^ Babylonian Talmud, Menahot 86b]

- ^ Yoma 39a

- ^ a b Povoledo, Elisabetta (20 February 2017). "Vatican and Rome's Jewish Museum Team Up for Menorah Exhibit". The New York Times. Retrieved 18 May 2017.

- ^ Edward Gibbon: The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire (Volume 7: Chapter XLI. From the Online Library of Liberty. The J. B. Bury edition, in 12 volumes.)

- ^ Procopius, Vandal Wars, Book IV. ix. 5.

- ^ Procopius, Vandal Wars, Book IV. ix. 9.

- ^ Avot of Rabbi Natan 41:12

- ^ Chanan Morrison, Abraham Isaac Kook, Gold from the Land of Israel: A New Light on the Weekly Torah Portion - From the Writings of Rabbi Abraham Isaac HaKohen Kook, page 239 (Urim Publications, 2006). ISBN 965-7108-92-6

- ^ Epstein, Isadore, ed. (1976). Babylonian Talmud: Tractate Baba Bathra (English and Hebrew ed.). Soncino Press. p. 12a. ISBN 978-0900689642.

- ^ Rev. 1:12,20

- ^ p.10, Morals and Dogma of the Ancient and Accepted Scottish Rite of Freemasonry by Albert Pike (L.H. Jenkins, 1871 [1948])

- ^ Robert Lewis Berman, A House of David in the Land of Jesus, page 18 (Pelican, 2007). ISBN 978-1-58980-720-4

- ^ NASB, The Lockman Foundation, 1995

- ^ Kevin Conner, The Tabernacle of Moses, City Christian Publishing (1976), p43

- ^ Kevin Conner, The Tabernacle of Moses, City Christian Publishing (1976), p43-44

- ^ Jerusalem Post. "More than a Model Menorah" [1] 13 December 2011

- ^ Hapgood, Isabel (1975) [1922]. "Service Book of the Holy Orthodox-Catholic Apostolic Church" (5th ed.). Englewood NJ: Antiochian Orthodox Christian Archdiocese: xxx. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - ^ Jeaneane D. Fowler, An Introduction to the Philosophy and Religion of Taoism: Pathways to Immortality, page 213 (Sussex Academic Press, 2005). ISBN 1-84519-085-8

Further reading[edit]

- Fine, Steven. 2010. "'The Lamps of Israel': The Menorah as a Jewish Symbol." In Art and Judaism in the Greco-Roman World: Toward a New Jewish Archaeology. By Steven Fine, 148–163. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- --. 2016. The Menorah: From the Bible to Modern Israel. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2016.

- Hachlili, Rachel. 2001. The Menorah, the Ancient Seven-Armed Candelabrum: Origin, Form, and Significance. Leiden: E.J. Brill.

- Levine, Lee I. 2000. "The History and Significance of the Menorah in Antiquity." In From Dura to Sepphoris: Studies in Jewish Art and Society in Late Antiquity. Edited by Lee I. Levine and Ze’ev Weiss, 131–53. Supplement 40. Portsmouth, RI: Journal of Roman Archaeology.

- Williams, Margaret H. 2013. "The Menorah in a Sepulchral Context: A Protective, Apotropaic Symbol?" In The Image and Its Prohibition in Jewish Antiquity. Edited by Sarah Pearce, 77–88. Journal of Jewish Studies, Supplement 2. Oxford: Journal of Jewish Studies.

External links[edit]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Menorah. |

| Library resources about Menorah (Temple) |